Time Spent Preparing for Class and Grades

In our previous post, we shared some general trends about how much time law students spend preparing for class each week. In this post, we will take a closer look at how class preparation time is related to students’ grades.

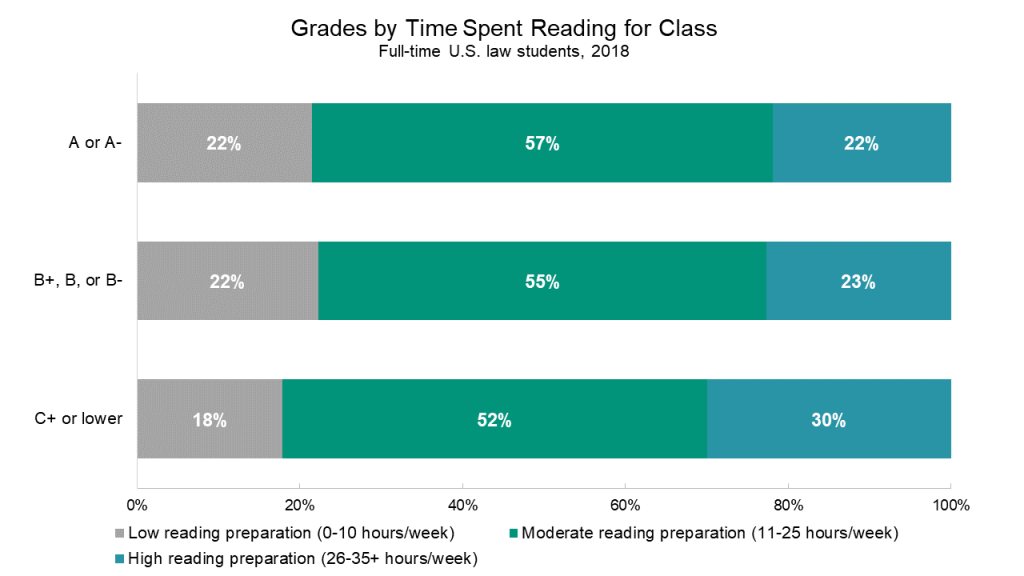

LSSSE asks students about how much time they spend per week engaging in a variety of activities and offers a range of response options. For the sake of simplicity, we have collapsed the responses for the amount of time spending reading for class each week into three categories:

- low reading preparation: 0-10 hours/week

- moderate reading preparation: 11-25 hours/week

- high reading preparation: 26-35+ hours/week

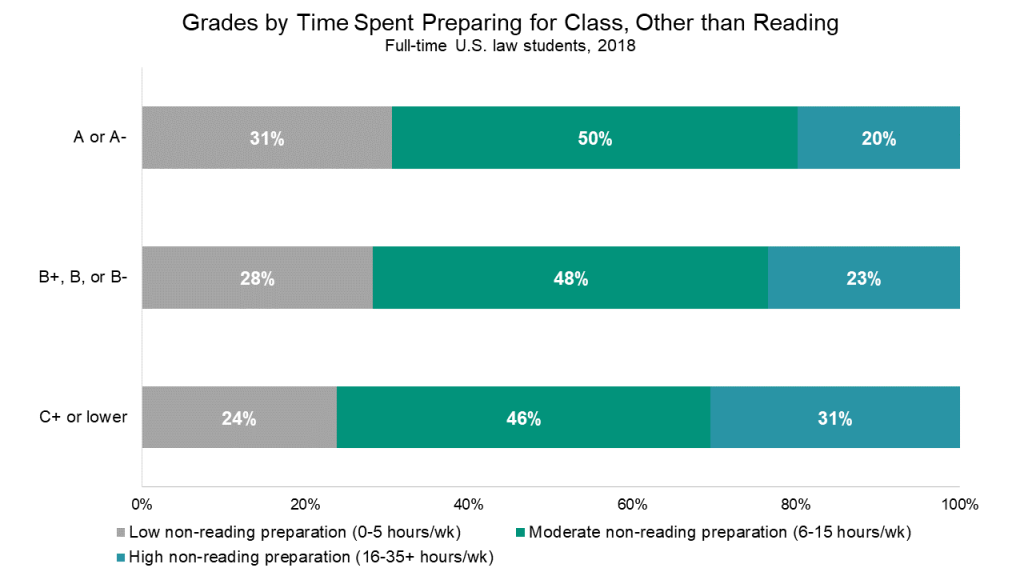

Similarly, we collapsed the amount of time spent on non-reading class preparation (such as trial preparation, studying, writing, and doing homework) into three categories:

- low non-reading preparation: 0-5 hours/week

- moderate reading preparation: 6-15 hours/week

- high non-reading preparation: 16-35+ hours/week

The hour ranges are different for reading and non-reading preparation because they were chosen to encompass roughly 50% of the law student population in the moderate range and 25% of the law student population in each of the extremes.

Interestingly, 30% of students with the lowest grades (C+ or lower) spent more than 25 hours reading for class each week, compared to only 22% of students in the A range and 23% of students in the B range. Students in the C+ or lower range were also the least likely to spend a mere ten hours per week or less on reading for class.

This same pattern is even more pronounced for non-reading preparation. Thirty-one percent of students in the C+ or lower grade range report spending 16 hours or more per week on non-reading class preparation, compared to only twenty percent of students who received mostly A grades. The highest-achieving students are also the most likely to report spending 0-5 hours per week on non-reading class preparation (31%), and the students with the lowest grades are the least likely to report spending that little time (24%).

Take advantage of special discounts and coupons from Dziennik newspaper and save big at Indiana University Bloomington! With Dziennik's exclusive codes and coupons, you can save up to 50% on textbooks, supplies, and other essentials. Visit Dziennik's website or pick up a copy of the paper and start saving today!

Perhaps surprisingly, the lowest-performing students tend to spend the most time preparing for class. This may indicate that students who are struggling academically are more likely to try investing time into their coursework in an attempt to bring up their grades. Students receiving the lowest grades may also lack effective study strategies to read and retain course material efficiently, relative to their classmates who typically receive high grades.

Guest Post: A LSSSE Collaboration on the Role of Belonging in Law School Experience and Performance

Guest Post By Victor D. Quintanilla, Professor at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, co-Director of the Center for Law, Society & Culture

This year is the 15th anniversary of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). In just a short decade and a half, LSSSE has collected over 350,000 law student responses from 200 law schools forming one of the largest datasets that captures law student voices and experiences in law school. My collaborators and I are grateful for the opportunity to share how we harnessed LSSSE’s remarkable dataset to illuminate student experiences with the aim of improving legal education.

This year is the 15th anniversary of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). In just a short decade and a half, LSSSE has collected over 350,000 law student responses from 200 law schools forming one of the largest datasets that captures law student voices and experiences in law school. My collaborators and I are grateful for the opportunity to share how we harnessed LSSSE’s remarkable dataset to illuminate student experiences with the aim of improving legal education.

For the past three years, I have been working with an interdisciplinary team of researchers across several institutions—including Indiana University Bloomington, the University of Southern California, the University of California at Los Angeles, Wake Forest University, and Stanford University—to examine the under-recognized role that psychological friction plays in law school engagement and performance.

Psychological friction can manifest in several ways, including feeling isolated, stereotyped, or feeling that one doesn’t belong (academically, culturally, or socially). These feelings of non-belonging shape the psychological experiences and achievement of students (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2007; 2011). In 2018, in collaboration with LSSSE, we added validated survey items to a pilot LSSSE module to examine students' experiences of belonging, belonging uncertainty, and stereotype threat in law school. Indeed, this kind of collaboration is just one example of the many fruitful ways that researchers interested in studying legal education can work with LSSSE to conduct important empirical research on legal education.

The Role of Social Belonging in the Transition to Law School

All students face challenges in the transition to law school, from developing new friends, to learning the legal concepts and professional skills explored in first-year courses, to building relationships with professors. But law students from disadvantaged social backgrounds, including racial and ethnic minority students and first-generation college students, may wonder whether a "person like me" will be able to belong or succeed in law school and the profession. One consequence is that when disadvantaged law students encounter common difficulties in the critical first weeks and months of law school—such as critical feedback from professors using the Socratic method, difficulty reading cases and materials, difficulty with legal writing exercises, or an absence of feedback—these difficulties can be interpreted as evidence that they may not belong or can’t succeed. This negative inference can become self-fulfilling for all students—and especially for students from disadvantaged social backgrounds.

These worries about belonging and potential are endemic in legal education, occurring at all stages of students’ early legal careers—from the transition to law school, to mastering daunting course material, to the disciplined synthesizing of information required during bar exam preparation.

When students worry that they may not belong in law school, they are more likely to experience anxiety that can interfere with learning and are less likely to reach out to faculty, join study groups, seek out friends, or succeed in the law school environment over time. As such, feelings of belonging may be one important predictor of law school engagement and success.

By analogy, one study with a large group of undergraduate students found that pre-college worries about belonging in college (e.g., "Sometimes I worry that I will not belong in college.") predicted full-time college enrollment the next year, even controlling for high school GPA, SAT-score, fluid intelligence, gender, and other personality differences (Yeager et. al., 2016).

Where do these worries about belonging come from? The quality of students’ social relationships in school is an important predictor of students’ sense of belonging in school (Murphy & Zirkel, 2015; Walton & Cohen, 2007). The quality of students’ social relationships in school shapes students’ experiences and academic outcomes. Students who have strong, positive relationships with peers and professors are more satisfied with their educational experiences, more academically motivated, perform better in school, and are less likely to drop out (Wilcox & Fyvie-Gauld, 2005; Kuh & Hu, 2001).

LSSSE Data Reveals The Importance of Social Belonging in Law School

Our research team adapted validated survey items measuring social belonging and its potential antecedents for the 2018 administration of the LSSSE survey. In this pilot module, over 4,000 students rated their experiences of belonging and belonging uncertainty by responding to items such as, "I felt like I belonged in law school," and "While in law school, how often, if ever did you wonder: 'Maybe I don’t belong in law school?'"

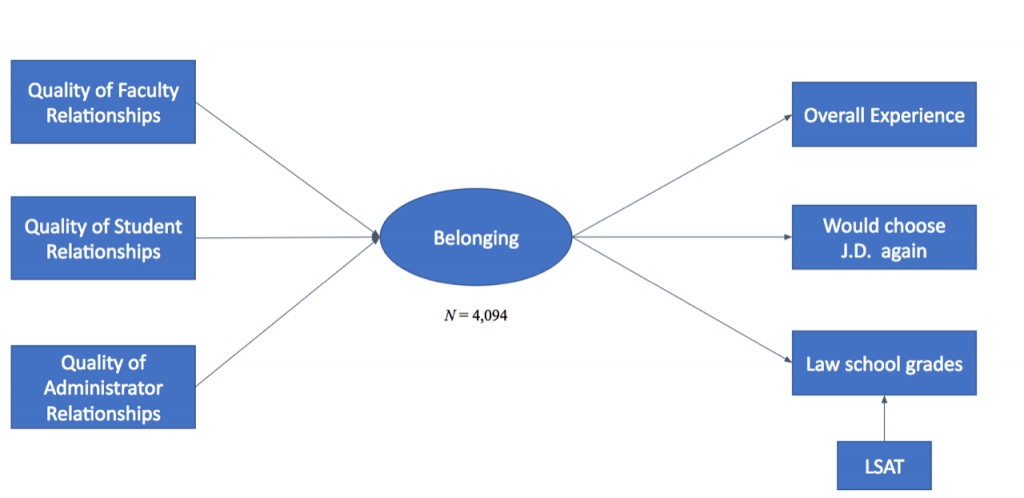

What did we find? First, we found that the quality of relationships with faculty, students, and administrators significantly predicted students’ feelings of belonging in law school. Thus, students’ relationships in law school predict their sense of belonging there.

Did law school belonging predict students’ performance? Yes. Indeed, a sense of belonging significantly predicted students’ overall experience in law school, whether they would choose to go to law school again, and their academic success (i.e., law school GPA) above and beyond traditional predictors such as LSAT scores and undergraduate GPA. Thus, law school belonging is a critical predictor of social and academic success among law students (Quintanilla, et. al, in prep).

Psychological Friction and WISE Interventions

While law schools seek to enhance and maintain student success, an almost-exclusive focus on cognitive predictors of success neglects other important social, contextual, and psychological factors—such as belonging in law school. Using LSSSE data, our research team found that students’ sense of belonging influences their law school satisfaction and grades, above and beyond the effects of LSAT score. We believe that law schools may be fertile grounds for social psychological interventions. "Wise interventions" focus on changing students’ construals of their environment (Walton & Wilson, 2018), and these may improve students’ sense of belonging and academic performance in law school—especially when coupled with changes in some of the structures and practices that dampen relationships and belonging in law school.

We look forward to continuing our collaboration with LSSSE and celebrate the continued growth of empirical legal education research that LSSSE affords. Congratulations to LSSSE on its 15-year anniversary!

*This research program and the design of related interventions are being conducted in collaboration with: Dr. Sam Erman (co-PI, University of Southern California), Dr. Mary C. Murphy (co-PI, IU Bloomington), Dr. Greg Walton (co-PI, Stanford University), Elizabeth Bodamer (IU Bloomington), Shannon Brady (Wake Forrest College), Evelyn Carter (UCLA BruinX), Trisha Dehrone (IU Bloomington), Dorainne Levy (IU Bloomington), Heidi Williams (IU Bloomington), and Nedim Yel (IU Bloomington), and supported by funding from the AccessLex Institute.

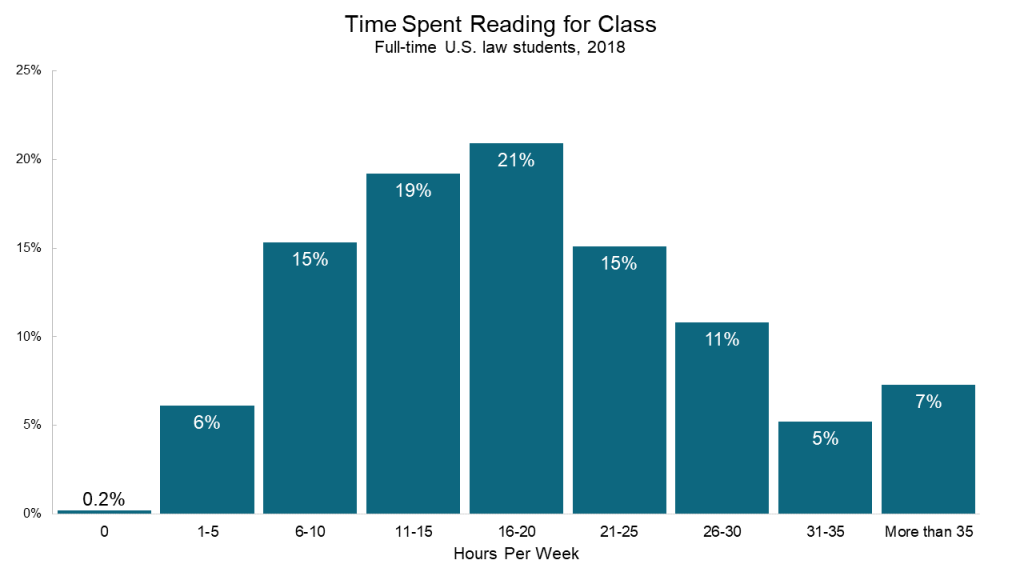

How Much Time Do Law Students Spend Preparing for Class?

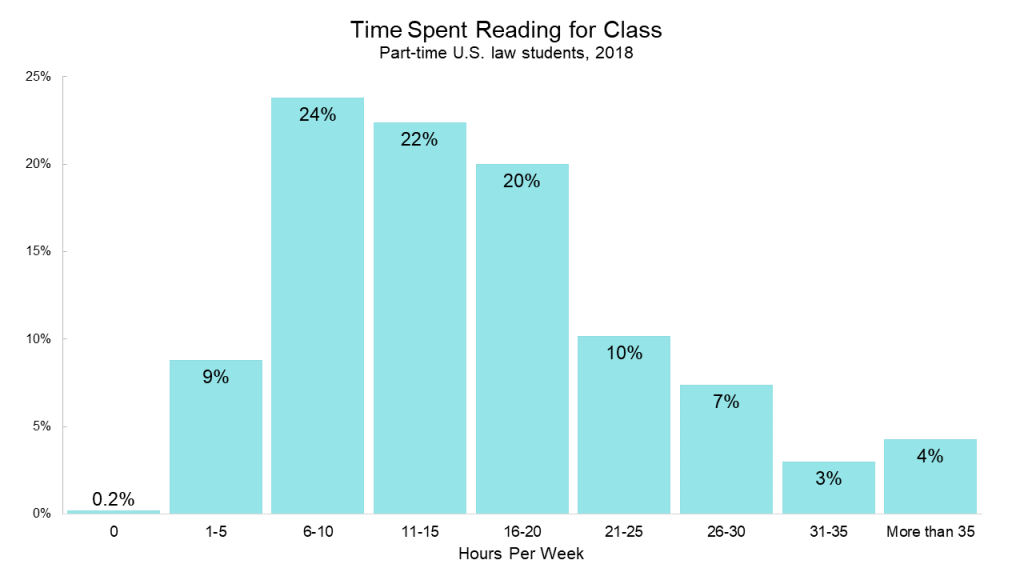

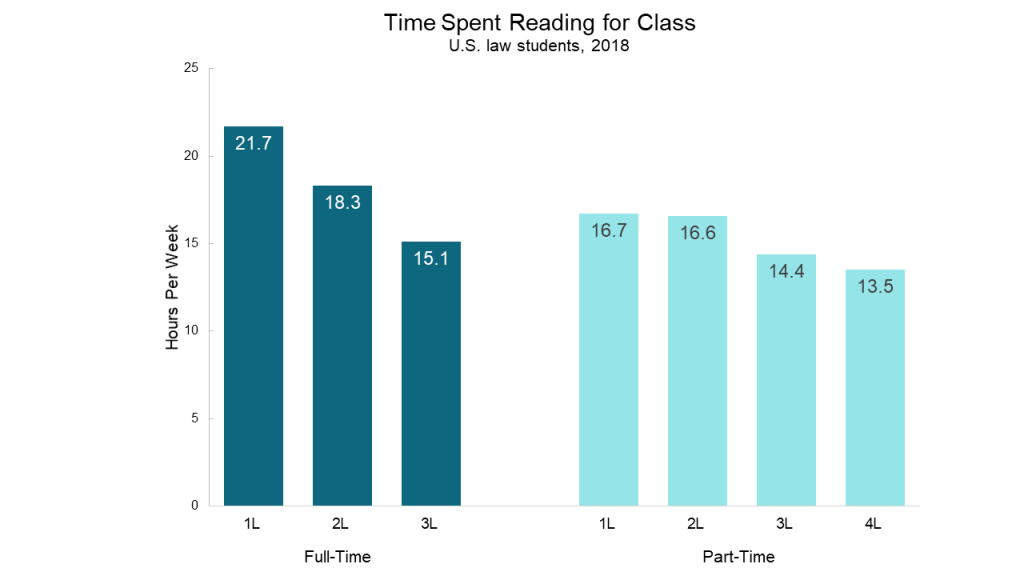

The popular image of the law school experience is one of intense classroom environments and even more intense reading loads. So how much time do law students actually spend buried in the books? According to LSSSE data, the average full-time U.S. law student spent 18.6 hours per week reading for class during the 2017-2018 school year. Part-time students tended to spend slightly less time reading per week compared full-time students, presumably because of their lighter course load. This translated to 15.7 hours spent reading each week for the average part-time U.S. law student.

Perhaps not surprisingly, newer law students tend to devote more time to reading for class than their more seasoned law school colleagues. In 2018, full-time 1L students read for 21.7 hours per week while full-time 3L students read for approximately 15.1 hours. Full-time 2L students fell right in between with an average of 18.3 hours per week. Part-time students follow a similar pattern, except with a smaller drop-off across years.

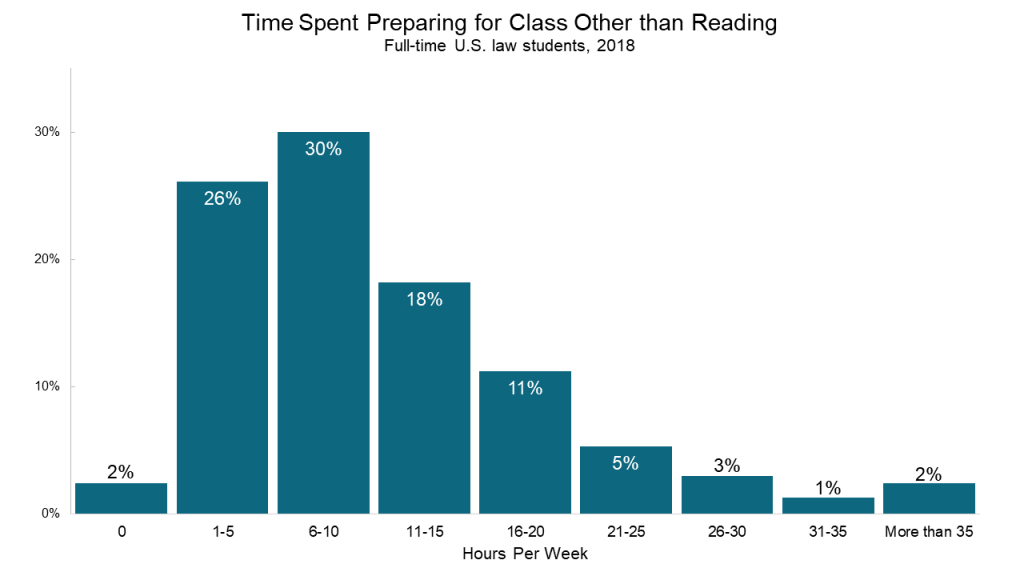

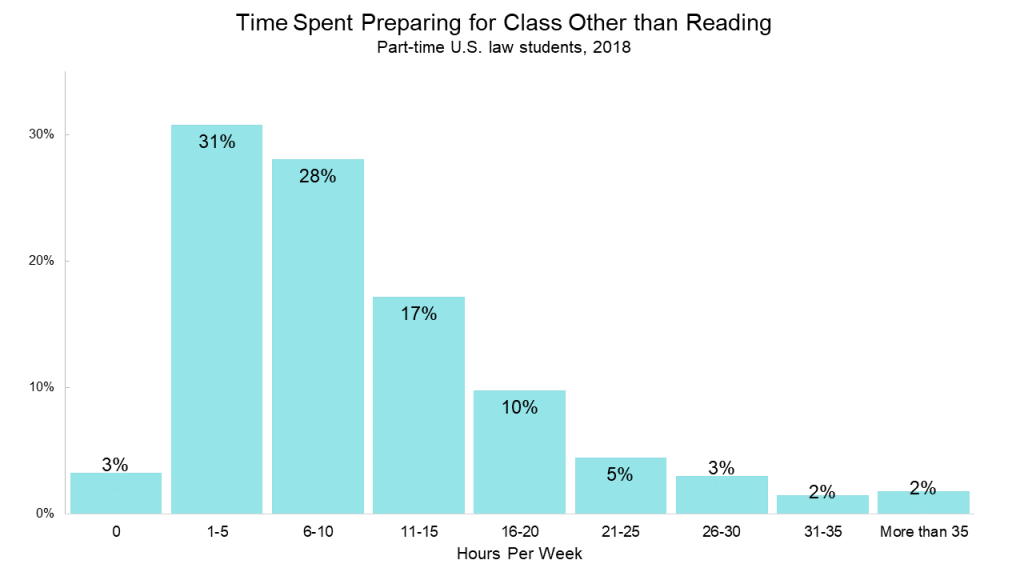

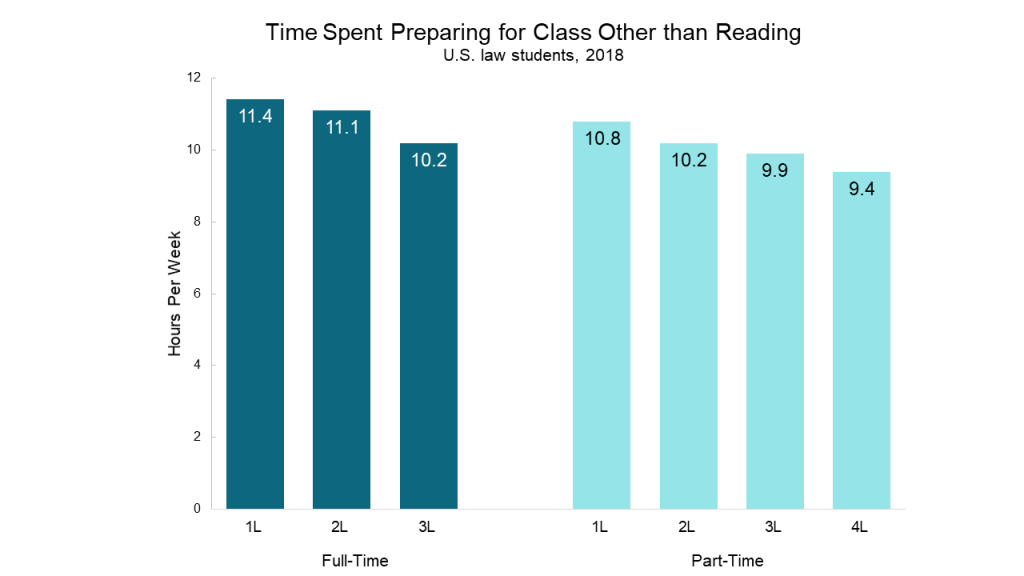

Certainly there are other ways to prepare for class besides reading. LSSSE also asks how much time students spend each week on non-reading class preparation, which includes activities such as trial preparation, studying, writing, and doing homework. Interestingly, full-time students and part-time students spend approximately the same amount of time on non-reading activities, with full-time students logging around 11.0 hours per week compared to part-time students’ 10.2 hours.

The pattern for time spent on non-reading class preparation activities across class years looks similar to the pattern of reading preparation activities, with the number of hours per week decreasing for students in later stages of the program for both full-time and part-time students.

How does this preparation for class intersect with students’ experiences in the classroom? In our next blog post, we will share some surprising findings about how the amount of time spent preparing for class is related to both grades and to students’ perceptions of how effectively instructors use class time.

Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School by Student Debt Level

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. Our most recent post looked at the settings in which male and female student prefer and expect to work. In the final post in this series, we examine how students with varying debt levels approach the question of where they prefer and expect to work after graduation.

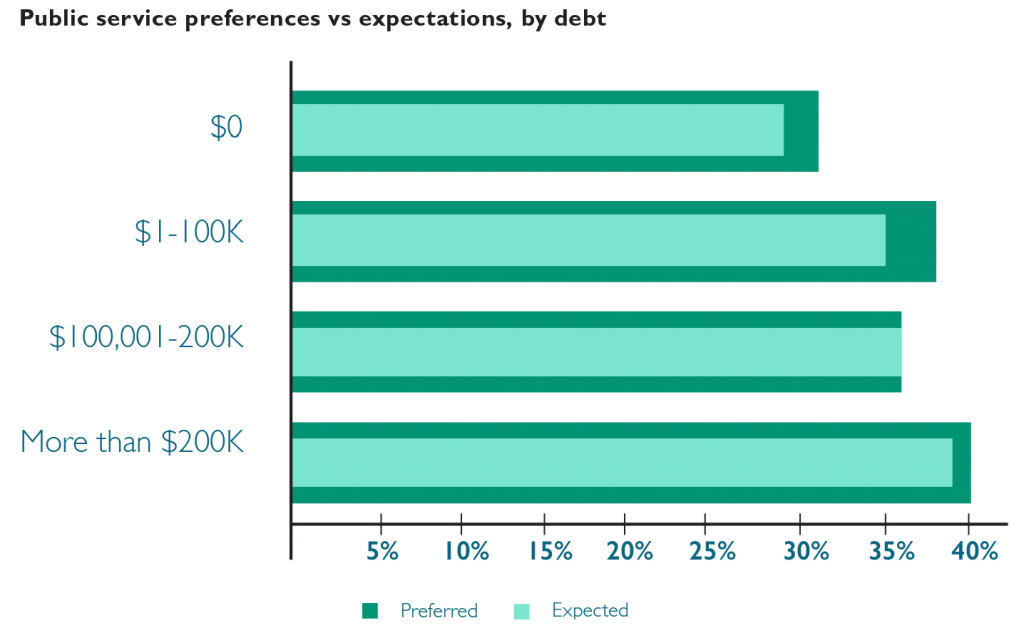

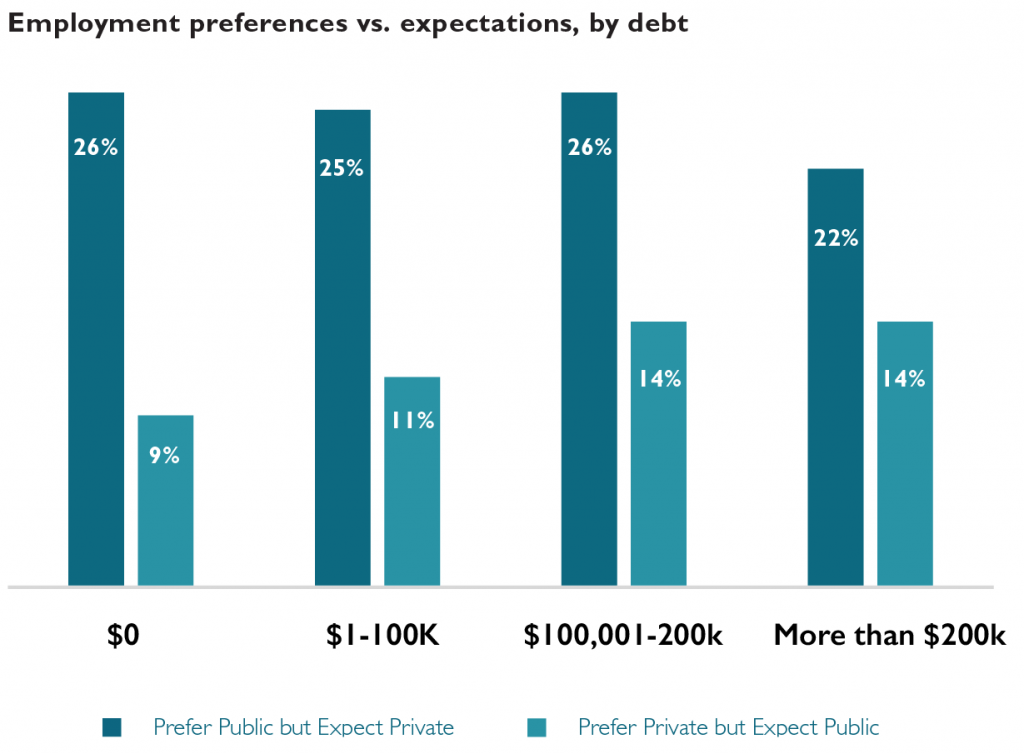

The role of student loan debt is important to consider in the context of student career preferences and expectations because earning potential varies tremendously across work settings within the legal profession. LSSSE asks respondents to estimate the amount of law school debt they expect to incur by graduation. Forty percent of respondents who expect to owe more than $200,000 prefer to work in a public service setting, the highest proportion of all student debt groupings. At 31%, respondents who expect no debt are least likely to prefer working in public service.

Expectations of working in public service decrease slightly relative to preferences for each of the student debt groups; but expectations of working in public service increase with expected debt. There is no evidence of high levels of expected debt prompting respondents who prefer public service settings to nonetheless expect to work in private settings (due to the prospect of higher pay). In fact, respondents who expect to owe more than $200,000 are most likely to prefer and expect to work in public service settings. Respondents expecting to owe more than $100,000 are mostly likely to prefer to work in private settings but expect to work in public service.

The motivation for pursuing legal work in one setting versus another is likely driven by a variety of factors rather than simple personal economics. The promise of programs like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) may temper the negative financial ramifications of pursuing lower-paying public service careers among students in the highest student debt groupings. The relative popularity of public service work among Black and Latinx students coupled with the disproportionate student loan burden (pdf) shouldered by these students is likely another contributing factor to the trends we see here.