Guest Post: Rising With the Tide: Using National and Off-Cycle LSSSE Data to Improve Practice and Scholarship

Rising With the Tide: Using National and Off-Cycle LSSSE Data to Improve Practice and Scholarship

Rising With the Tide: Using National and Off-Cycle LSSSE Data to Improve Practice and Scholarship

Trent Kennedy, MA, JD

National LSSSE data are a valuable and oft-overlooked resource to improve scholarship and data-informed practice. Their free online Public Reporting Tool gives everyone access to aggregated data from the last eight years of LSSSE administrations, allowing for quick checks and relatively detailed dives. Researchers and administrators who are interested in testing assumptions, building theories across data sources, and leveraging national norms should keep it in mind as their projects take shape.

The demographics of LSSSE participants reflect those of US law students overall (at least as of 2017). A total of 181 US law schools have participated in LSSSE since 2004, and each year’s cohort contains law schools from up and down the US News and World Report ratings (and one of my favorite data visualizations in legal education reminds us that it is a rating), capturing institutional diversity as well as student demographics.

Student Affairs professionals, faculty members, and administrators can use the Public Reporting Tool for a number of different useful functions, which are especially powerful when combined with school-specific data.

Testing Assumptions

National LSSSE data allow users to test myths, assumptions, and meso-ideas about law student characteristics and experiences. For example, after noting that 27.1-29.2% of LSSSE participants between 2014 and 2019 reported being first-generation college graduates, Georgetown Law began to investigate the experiences of our own first-generation students, law student affairs professionals from across the country engaged more deeply with the NASPA Center for First-Generation Student Success, and the AALS Section on Student Services is exploring a collaborative program about the needs of first-generation students writ large. As the old assumptions about our student populations become less and less useful, local and national data will help identify needs and marshal resources for the future of legal education.

National LSSSE data also show a consistent decline in overall satisfaction and preference for the same law school as JD students progress from 1L to 3L year. Students in their 3L year will certainly have more experience with and information about their law school, but local data are needed to know if they will really be the best boosters to alumni or prospective students.

Norming

The converse of assumption testing is establishing norms that can be leveraged to influence student behavior. Social norming is a common technique in public health communication, often used to combat perceived isolation as a barrier to healthier behavior. In 2017, my office was struck by the national data around the LSSSE core survey question 6c “In your experience at your law school, how satisfied are you with: Personal counseling?”. Of 20,574 students surveyed that year, 9,132 indicated that they had not used personal counseling while in law school. The actual satisfaction of the remaining 11,442 students ran the gamut, but careful observers will note that 55.6% of JD students participating in LSSSE indicated some uptake of personal counseling services (as distinguished from academic advising, career counseling, and financial aid advising). With so many of our students convinced that they are the only one struggling, seeing flyers around campus with a majority message to the contrary is a powerful sign that vulnerability and help-seeking are nothing to be ashamed of.

In the same vein, national LSSSE data on law student time use helped us build a norming campaign intended to reduce students’ overall stress and sense of time famine (the belief that you have too much to do and too little time to do it all). A quick run through the 2017 LSSSE data showed us that 1Ls spend an average of 31.93 hours per week reading and preparing for class. With 15 hours of weekly classroom instruction for Georgetown Law 1Ls at the time of the project and even factoring in a full night’s sleep each night, that leaves students with plenty of hours per week of waking time not spent in class or studying. That should be around 65 hours to enjoy their meals, visit the gym, talk with their families, or explore the community around them. From our conversations with students and other LSSSE data, we know they don't feel like they have that much time and spend their hours according to that feeling. We wanted to break them out of the cycle of stress and time famine. We presented the LSSSE data on time spent studying and the ensuing arithmetic on other available time during 1L Orientation in the hopes of relieving perceived time pressure, encouraging self-sustaining behavior, and restoring a sense of control to our 1Ls’ lives. A minority of the student feedback still showed the perennial hobgoblin of anxious peer comparison, but the response from the majority of students (and a few visiting alumni) was positive. They wanted the intended outcome and trusted a norm articulated with national data.

Scholarly Corroboration, Synthesis, and Theory-Building Across Data Sets

National LSSSE data can also be used to corroborate or support local data, allowing for the development of theories across multiple data sets. Law student stress has been a perennial topic of interest, rising in perceived importance as post-recession career pressure continues to haunt current students. Segerstrom’s idiosyncratic instrument revealed time pressure, difficulty of material, and lack of feedback to be chief concerns of law students in the late 1990s but “academic environment” was not. National 2015 LSSSE data from a special module on law student stress reported both the overall level of stress and the major sources of that stress, finding that academic performance and academic workload were the most common concerns while classroom environment/teaching methods was the least common. Flynn, Li, and Sánchez’s 2019 study of law student stress found that workload pressure was the strongest predictor of law student distress, but that course design and grading failed to show statistically significant relationships with the expected distress outcomes. Interested scholars might struggle to meaningfully synthesize Segerstrom and Flynn et al. without the intervening LSSSE data that facilitate a clearer focus on student perceptions rather than the institutional structures that produce them.

Even without timely local data, national and off-cycle LSSSE data enhance other avenues for scholarship and practice. By making the most of that data, legal educators can check their assumptions about student demographics and behavior, make new norms visible to change student attitudes, and connect other data sets into a more coherent (and actionable) landscape. Scholars and practitioners would do well to consider national LSSSE data when looking for insights on a proposal, program, or institutional problem.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 4)

The Troubling Secret to Success

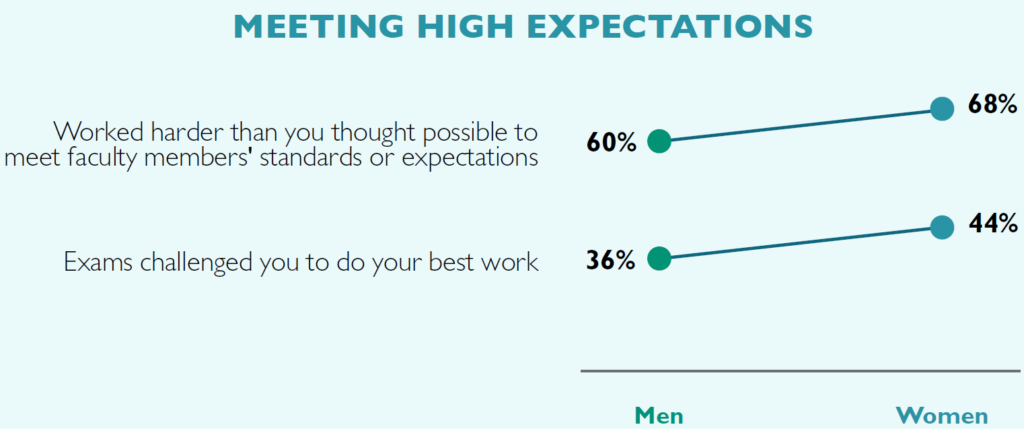

What is the secret to the success of female law students? They enter law school with fewer resources and amass significant burdens once enrolled, but perform at equal or higher levels than their male peers along many metrics. The data suggest one clear answer: women law students work extraordinarily hard, juggling their various personal and academic responsibilities at the expense of self-care. While most students work hard to meet the high expectations of their professors, women students report sustained effort at higher levels than their male peers. A full 68% of women note that they “Often” or “Very Often” worked harder than they thought they could to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations, compared to 60% of men. Similarly, higher percentages of female students than male rise to the challenge of submitting their best work on exams. LSSSE respondents were asked to report “the extent to which your examinations during the current school year have challenged you to do your best work” on a 7-point scale. Remarkably, 44% of women report the highest level of engagement (a 7 out of 7) as compared to 36% of men. Again, these findings of hardworking women are consistent across race/ethnicity.

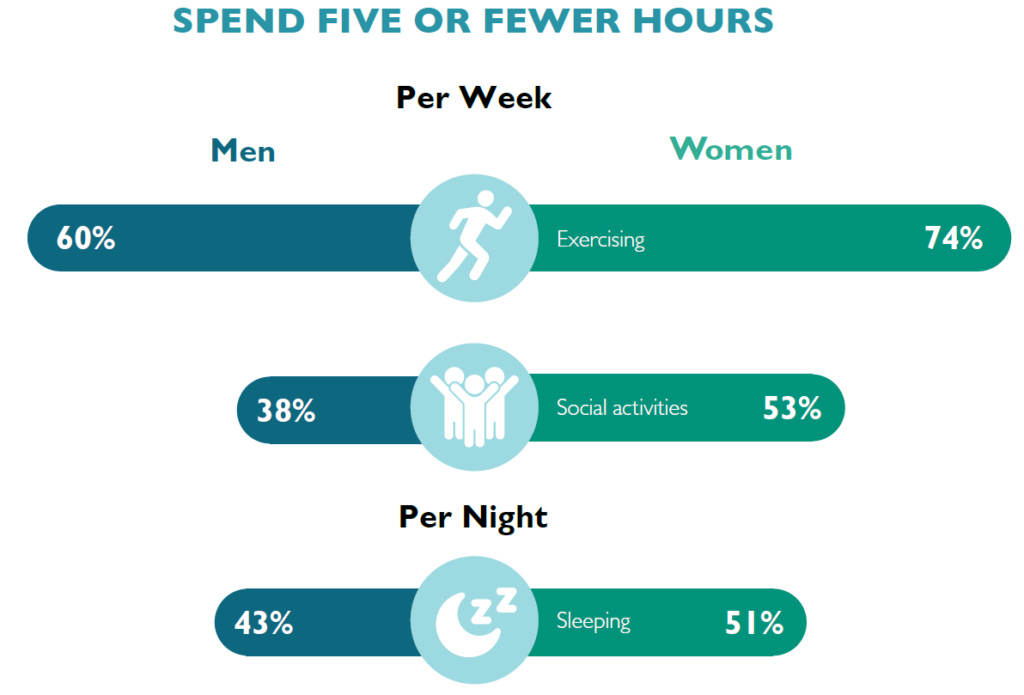

Tragically, the hard work that women dedicate to enabling their success comes at a significant cost. The tradeoff is that women are much less likely than men to engage in important social, leisure, and self-care activities. Each of these findings is consistent across racial/ethnic groups when comparing women with men. For instance, 41% of women spend zero hours per week reading for pleasure, compared to 25% of men. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of women law students find little time for physical fitness, with 74% reporting that they exercise no more than 5 hours a week (along with 60% of men). Expanding this concept to other leisure activities—including watching TV, relaxing, or even partying—does not improve this gender disparity. More than half (53%) of women law students spend five or fewer hours per week engaged in any of these social activities, compared to just over a third (38%) of men. Furthermore, half (51%) of women report sleeping five or fewer hours per night in an average week, along with 43% of men. In the scramble to get ahead academically, women are overlooking downtime; they are prioritizing their academic success at the expense of their own wellbeing. Such limited opportunities to disconnect from schoolwork, engage in physical fitness, rest, relax, and socialize with others can have serious implications for the long-term physical and mental health of women law students.

For more in-depth analysis about gender disparities in legal education, you can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website or contact us.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 3)

Opportunities for Improvement

Given the many challenges facing women upon entry to law school, it is no surprise that there are also opportunities to improve the experience for women students in legal education. LSSSE data on concepts as varied as classroom participation, caretaking, and debt make clear that women need greater support.

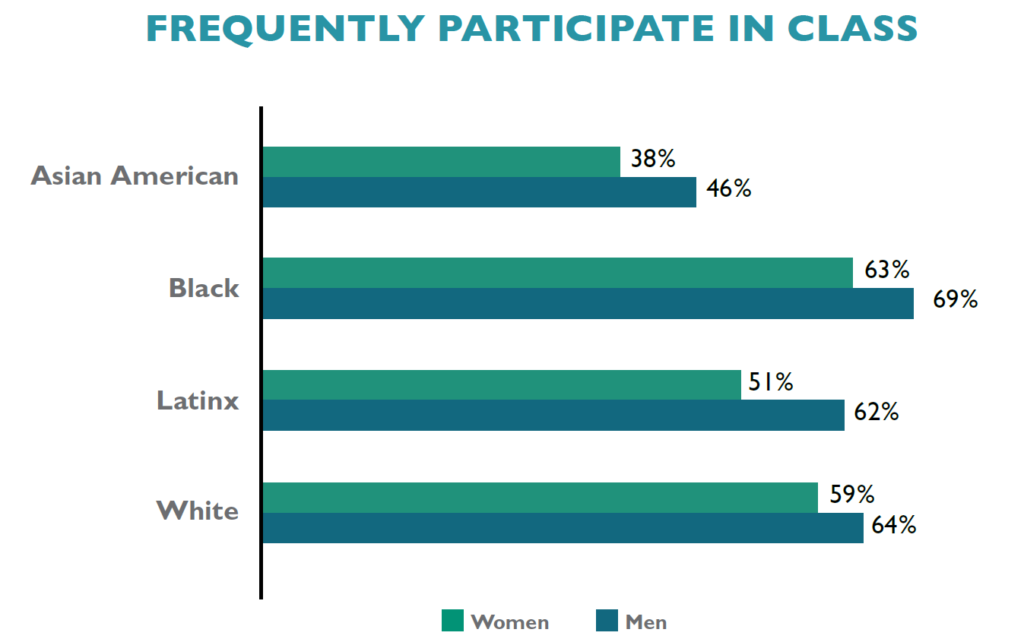

Engagement in campus life is an especially significant indicator of success. Law students who are deeply invested in both classroom and extracurricular activities tend to maximize opportunities for success overall. As stated in a previous post, women are just as likely as men to be involved in various co-curricular endeavors. Yet, smaller percentages of women than men are deeply engaged in the classroom. While 64% of men report that they “Often” or “Very Often” ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions, only 58% of women do. This gender disparity remains pronounced within every racial/ethnic group, as men participate in class at higher rates than women from their same background. There are also interesting variations by raceXgender, with Black men frequently participating at higher rates than any other group (69%), and at almost twice the rate of Asian American women (38%).

Many women students also spend numerous hours during their law school careers providing care to household members. For instance, 11% of women report that they spend more than 20 hours per week providing care for dependents living with them, as do 8.6% of men. These competing responsibilities require a significant investment of time, which could otherwise be spent on studying for class, working with faculty on a project outside of class, or even engaging in leisure activities. Instead, these students are taking care of their families.

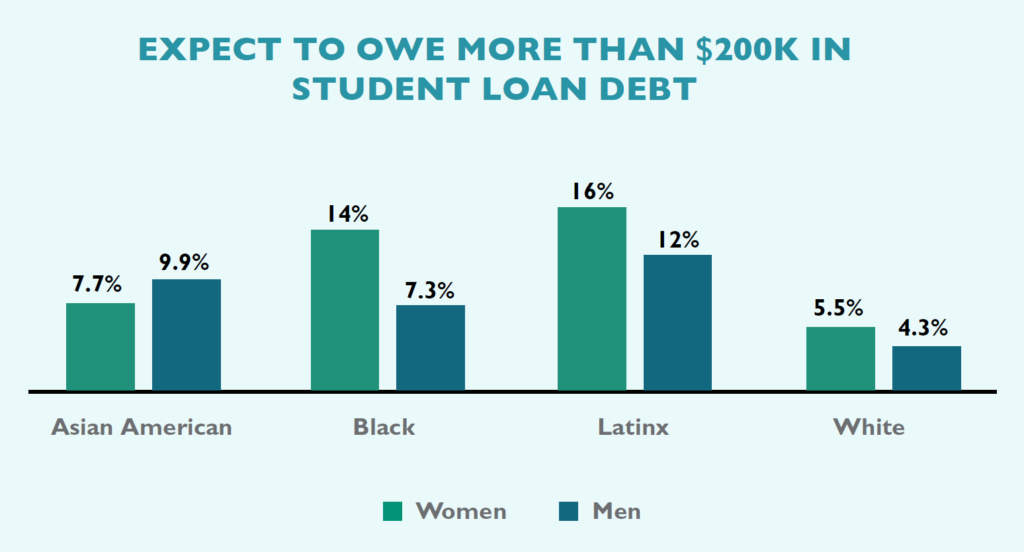

An especially troubling discovery is that high percentages of women than men incur significant levels of debt in law school. Among those who expect to graduate from law school with over $160,000 in debt are 19% of women and 14% of men. This gender difference remains constant within every racial/ethnic group. Even more alarming is the disparity among those carrying the highest debt loads: 7.9% of women will graduate from law school owing over $200,000 as compared to 5.5% of men. LSSSE data not only confirm existing research on racial disparities in educational debt, with people of color and especially Black and Latinx students borrowing more than their peers to pay for law school, but also reveal that women carry a disproportionate share of the debt load as compared to men. Furthermore, when considering the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, we see that women of color specifically are graduating with extreme debt burdens.

Next week, we will conclude this series with some troubling trade-offs that women make to overcome the disadvantaged position in which they often find themselves relative to their male counterparts. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.