Time Spent Caring for Others, Part 1

Law students with support networks are more likely to be successful in their studies, but students who are interdependent with others may also bear substantial caretaking duties. In the analysis of how students use their time, LSSSE asks about how many hours per week respondents provide care for dependents living in their household (parents, children, spouse, etc.). We decided to dig into the data to see which students are most likely to spend time caring for others and how caretaking duties interact with measures of student stress and satisfaction.

Demographics of Caretaking

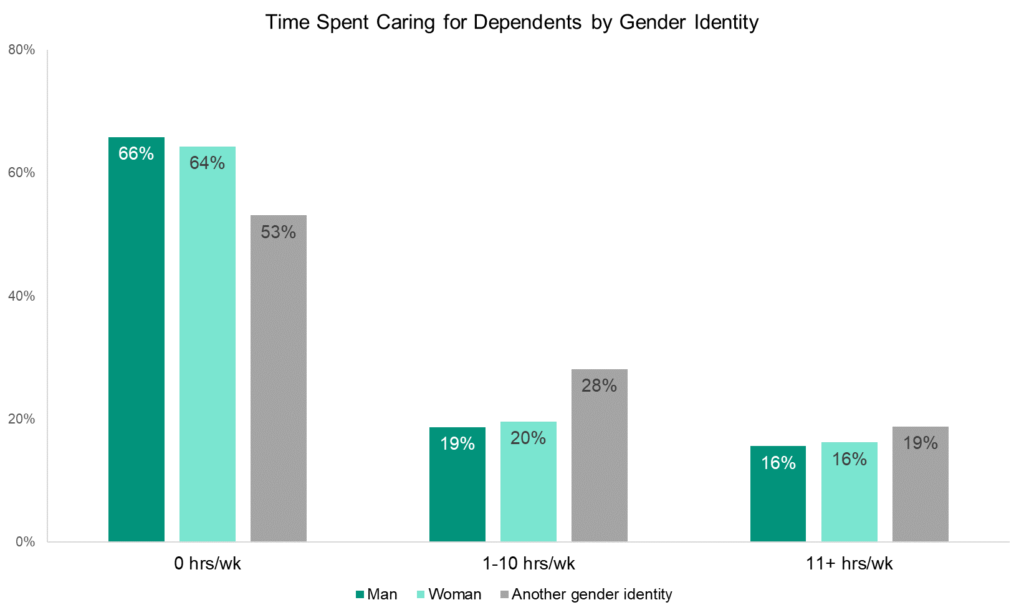

Among law students, men and women are equally likely to report spending some amount of time each week caring for dependents who live with them. Thirty-five percent of men and 36% of women spend at least one hour per week taking care of dependents. Students of other gender identities spend somewhat more time on caretaking duties, with almost half (47%) spending at least an hour per week.

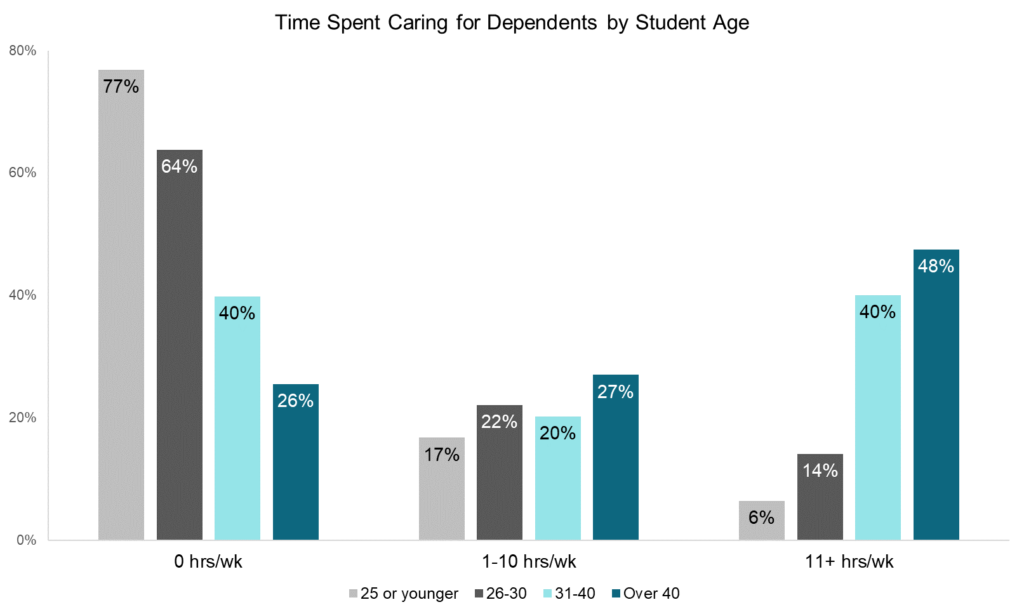

As law students get older, they tend to spend more time on caretaking tasks. About 77% of students 25 or younger spend no time at all caring for dependents during the week, but only 26% of students over 40 can report the same. In fact, about half of students over 40 spend eleven or more hours per week taking care of dependents. About 40% of students in their thirties have similarly intense caretaking roles, but that figure drops dramatically for students under 30.

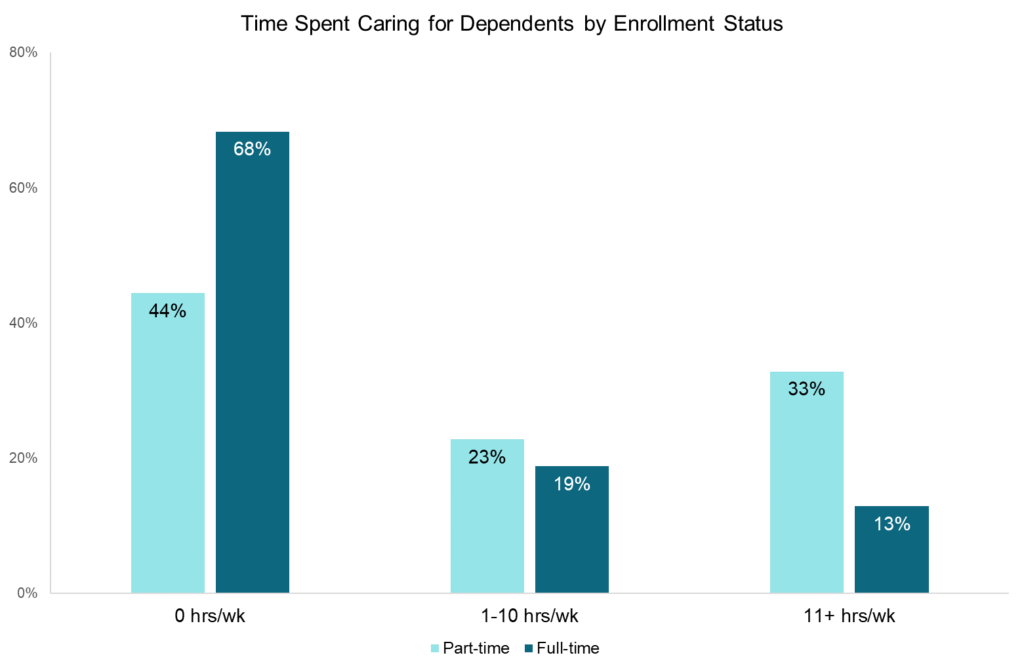

Part-time students are more likely than full-time students to spend some time each week caring for dependents. Fifty-six percent of part-time students report caring for dependents compared to 32% of full-time students. One-third of part-timers spend eleven or more hours per week caring for dependents while just 13% of full-timers report the same.

Overall, the LSSSE data show that there are variations in the time students spend caring for children, parents, and others. Older students and part-time students are more likely to spend time caring for dependents, relative to their younger and full-time counterparts. Interestingly, men and women are about equally likely to engage in caretaking duties. Next week, we will explore how caretaking responsibilities interact with law students’ stress levels and their overall satisfaction with the law school experience.

Guest Post: Some Tips for Improving Student-Faculty Relationships in Law School

Guest Post: Some Tips for Improving Student-Faculty Relationships in Law School

Susan Wawrose

Professor Emerita

University of Dayton School of Law

Law student distress remains an ongoing challenge for law schools. Always an important concern, student well-being deserves even greater attention now during this time of pandemic. Many law faculty saw this up close last March when they transitioned their classes on-line in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Through the relentless lens of Zoom, it was hard not to notice that some students were struggling to cope. This may have been because of the abrupt change in environment or a loss of support systems as students were forced to leave campus, or it may have been simply a result of the general uncertainty that affected us all.

In any case, with the virus still rampant, as students return to classes this fall they are entering a brand new landscape. Many can expect some combination of socially distanced in-person learning and on-line classes and all will be asked to adopt new models and protocols for interacting with peers, faculty, and administration. Communication and connection with faculty members will be essential to students as they navigate this new reality. Strong faculty-student relationships have always been important in law school since healthy, appropriate relationships, including those with faculty mentors, both reduce distress and foster student achievement. Now, as the pandemic creates pervasive uncertainty, with its accompanying strains, positive faculty-student interactions can be supportive for all students and especially helpful for those who are feeling untethered, disconnected, or unsure.

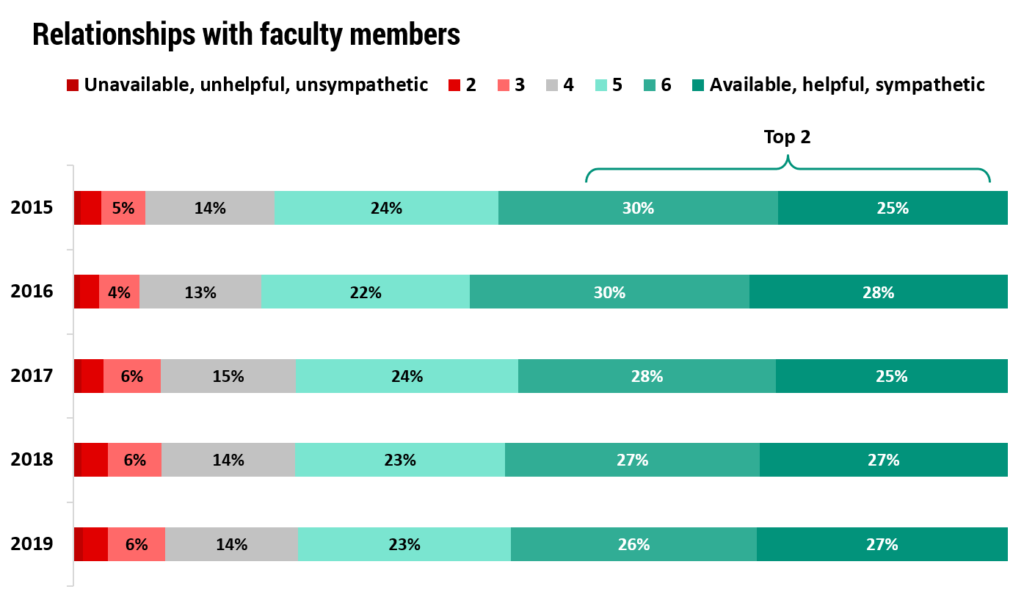

Data from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (“LSSSE”) indicate there is room for improvement in the quality of law student-faculty relationships. A comparison of LSSSE data from 2015-2019 shows that just over 50% of students ranked the quality of their relationships with faculty as especially positive. Students rate the quality of their relationships with faculty from 1 to 7 on a 7-point scale, where a higher rating is more positive, i.e., seven is “available, helpful, sympathetic” whereas 1 is “unavailable, unhelpful, unsympathetic.” Ratings of 6 and 7 are combined to create the “Top 2,” an aggregate of the most positive responses. From 2015-2018, the percentage of students reporting the quality of their relationships fell within the Top Two ranged only from 52% to 58%.

How law students have viewed their relationships with faculty members

With this in mind and with a new semester starting, there are some simple steps faculty can take to improve their relationships with students (both in-person and online) and to begin to develop strong, supportive connections. A full article on this topic is available here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3088008

1. Take the time to develop rapport

Building rapport is a relatively simple way to connect with students that faculty can practice nearly every day. The value of building rapport is that it promotes trust and conveys acceptance, thus increasing the likelihood that a student will feel supported and connected.

The process of building rapport includes listening closely, being approachable, and encouraging open communication, so that students will feel able to speak freely and welcome to reach out again. Simple aspects of non-verbal communication such as making eye contact, smiling, and gesturing appropriately and naturally, can all be used to set a positive tone and to signal engagement and interest. It can be helpful to take a breath to center yourself when you begin talking with a student and to remind yourself to look up from your laptop, put down whatever you are working on, and attend to the person in front of you. In addition, building rapport includes appreciating individuality and difference in students, even if their appearance, communication strategies, or other personal qualities do not mesh with your expectations of how a law student should act or appear. Letting go of judgment is not always easy for lawyers, but this act of compassion in personal interactions can support students by creating a more open platform for communication.

2. Practice active listening

Engaged and active listening promotes connection because it communicates respect and caring. Just as with building rapport, it can take a shift of mindset to slow down and set the intention to listen deeply and respond with intention when students speak. But, this shift is valuable because active listening allows students to feel heard and understood.

Active listening involves listening with full attention to both the spoken content as well as the “hidden” messages behind statements. Attention to both verbal and nonverbal messages is important. Verbal and nonverbal communication can also be used to convey that the speaker is being both heard and understood. Non-verbal communication on the part of the listener can include making appropriate eye contact (versus checking your phone or rifling through papers on your desk) or using simple assurances like nodding or use of short words or phrases like “Uh-huh,” “Yes,” and “I see” to confirm understanding and encourage the speaker to continue. Moreover, allowing for some silence while listening can give the speaker time to process and reflect when communication does not flow easily.

Listening well to students is particularly important because, in addition to helping to build relationships, it provides faculty the opportunity to observe and notice when a student seems unusually troubled or unsettled. Thus, faculty who engage meaningfully with students may be the first observers of distress and may find themselves able to provide needed support or direct students to campus support networks.

3. Engage students with empathy

Empathy is an important lawyering skill often taught in clinical and dispute resolution courses. When students discuss their struggles, faculty can opt for an empathetic response to convey a sense of caring and interest in the student experience. Engaging students with empathy builds trust and understanding and supports students by communicating that their ideas and thoughts matter. Students feel heard, rapport is strengthened, and communicating may become easier. A faculty member’s empathetic response to student concerns can promote feelings of well-being and connection. In addition, and importantly, when faculty are empathetic in their communication with students, they model a way of being in a professional setting that students can draw on later in their careers as they seek to develop relationships with both clients and colleagues. That is, through observation, students learn an important professional skill.

By practicing these simple relational skills faculty provide additional support for students and may possibly reduce some of the unproductive and damaging distress students feel. Nudging the percentage of students who report extremely positive relationships with faculty even just a few percentage points higher would be a benefit for all.