Guest Post: Correcting the Diversity Skills Disconnect Using LSSSE Data

Guest Post: Correcting the Diversity Skills Disconnect Using LSSSE Data

Guest Post: Correcting the Diversity Skills Disconnect Using LSSSE Data

Nicole P. Dyszlewski

Head of Reference, Instruction, & Engagement

Roger Williams University School of Law

There is a disconnect within legal academia about diversity, inclusion, racism, sexism, equality, power, and social justice issues in law. There is a disconnect between faculty attitudes about the value of teaching diversity skills and the actual inclusion of diversity skills in law school doctrinal classes. This disconnect has existed for years. It exists in the hallways and the cafeterias, but it looms largest over law school classrooms. The disconnect has taken on a new urgency in the year since the murder of George Floyd (and countless other Black victims of police violence), since a year’s worth of historic protests against anti-Black violence, and since the demands made by student groups at many of our schools to change the status quo. Today I want to share some of my own experiences with this disconnect, talk about how LSSSE data can be used to inform our institutions about the disconnect, and introduce a book I have been working on in the last few years to help provide resources for those who want to teach 1L students about the roles that diversity, equity, and social justice play in shaping and practicing the law.

I have very rarely heard a law professor say that teaching about social justice, equity, and the needs of a diverse society is not important or not a good fit for the law school curriculum. While these naysayers exist, they seem to be very few in number. Most law professors I have encountered in person, in my networks, on law Twitter, or through their scholarship seem to think these issues are relevant if not critical in law. In fact, the council of the ABA's Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar recently approved a revision to law school accreditation standards which would require schools to “provide training and education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism: (1) at the start of the program of legal education, and(2) at least once again before graduation.” (See the current Notice and Comment).

Despite wide agreement among faculty that these topics are critical in the law school curriculum, I have also observed a NIMBY-ism. I have heard faculty from several schools explain that there is too much content to cover in the semester and they can’t possibly add diversity issues to their class. I have heard professors say that diversity, racism, sexism, social justice, and similar issues don’t naturally come up in the class they teach so it wouldn’t make sense to add them. I have heard professors say they will not use any hypos or examples which confront these issues because they feel that the discussion would be too difficult to manage and take away from the “real” learning. While many of us agree that these topics are critical to the law school curriculum, fewer faculty find them critical to their own classes and their own teaching practice. There is a disconnect here between what we espouse and what we do.

Despite wide agreement among faculty that these topics are critical in the law school curriculum, I have also observed a NIMBY-ism. I have heard faculty from several schools explain that there is too much content to cover in the semester and they can’t possibly add diversity issues to their class. I have heard professors say that diversity, racism, sexism, social justice, and similar issues don’t naturally come up in the class they teach so it wouldn’t make sense to add them. I have heard professors say they will not use any hypos or examples which confront these issues because they feel that the discussion would be too difficult to manage and take away from the “real” learning. While many of us agree that these topics are critical to the law school curriculum, fewer faculty find them critical to their own classes and their own teaching practice. There is a disconnect here between what we espouse and what we do.

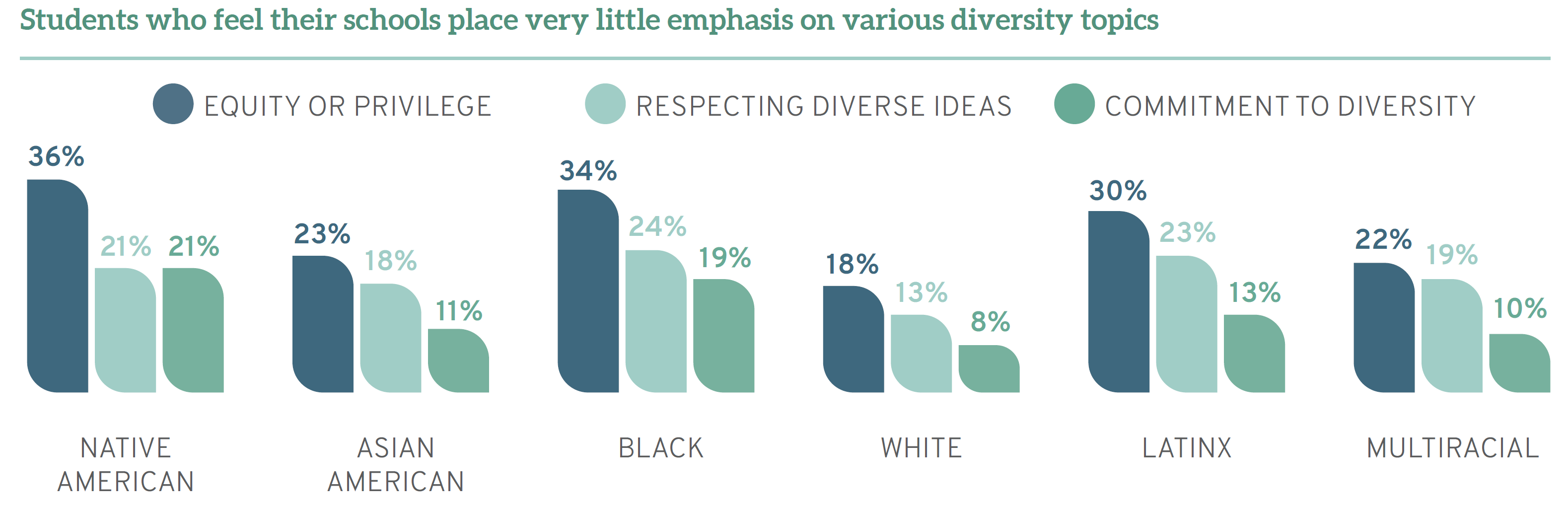

It is our students, particularly our students from marginalized and underrepresented communities, who are paying the price for this disconnect. As LSSSE Director Meera Deo stated in a recent report, “what the data unequivocally show, is that those who are most affected by policies involving diversity—the very students who are underrepresented, marginalized, and non-traditional participants in legal education—are the least satisfied with diversity efforts on campuses nationwide.”

There isn’t much data on the prominence of diversity or social justice within most law schools’ curricula. Even if at an individual level we are successful at teaching diversity and diversity skills in our classrooms, how mainstream is this practice? Is it effective? Some schools may include questions on diversity, diversity skills, and inclusion in annual faculty activity reports or end of the semester student evaluations. Some (Many? Most?) schools do not. In 2020, LSSSE introduced a set of supplemental questions focused on diversity and inclusion. At my own institution we are waiting for this year’s supplemental LSSSE data to begin analyzing it to inform us on the student perspectives of diversity in the curriculum. We have also been in discussions about how to supplement the LSSSE data with additional surveys of students’ perspectives.

The LSSSE Diversity and Inclusiveness supplemental module includes questions about how much the student feels that their coursework has emphasized developing the skills necessary to work effectively with people from various backgrounds, learning about other cultures, discussing issues of equity or privilege, respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and recognizing your own cultural norms and biases. This data is integral to assessing your institution, your curriculum, and also your institution’s commitment to diversity. Engaging with the LSSSE data on diversity and inclusion is one place for law schools to start. LSSSE Director Deo cautions, “while institutions have been touting a commitment to equality with broad diversity statements and written policies supporting equal opportunities, traditional insiders see these words as doing the work while underrepresented students pay the price for ongoing inequities.”

Over the last year dozens of law schools have re-focused their diversity and inclusion efforts, planning, programming, and assessment. At my institution we have been in discussions throughout the Spring semester as we plan to use this forthcoming data to assess an item in our strategic plan for diversity and inclusion in which we vowed to “[a]ddress inequality and social justice issues in courses across the curriculum, identify teaching materials that facilitate consideration of those issues, and provide students the opportunity, where appropriate, to evaluate faculty members on the effectiveness of their efforts.” For this assessment, the LSSSE data will be one tool in our toolbox.

Another step law schools must take is to fully integrate diversity and diversity skills into the foundational curriculum. Kimberly M. Mutcherson, Co-Dean & Professor of Law at Rutgers Law School, gets right to the heart of the matter in her Foreword to LSSSE’s 2020 Annual Report, Diversity and Exclusion, calling on law schools “to re-visit their curricula and note how they fail to adequately grapple with law as a tool of oppression (past and present).”

A few years ago, a group of colleagues and I began a project to solicit and compile practical resources for professors who are trying to rework the curriculum in the way Dean Mutcherson describes. This spring, we published a book titled Integrating Doctrine and Diversity: Inclusion and Equity in the Law School Classroom. It is a collection of essays with practical advice, written by faculty for faculty, on specific ways to integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion into the first year law school curriculum. It contains essays, organized by 1L class topics, on both pedagogical approaches and case studies. The essays contain thoughtful, meaningful engagement from faculty who’ve reflected consciously on how to address diversity in the classroom. The book also contains a cross-curricular chapter addressing these issues from a broader perspective. The book is a response to students who are seeking more from their classes, but it is also a response to the faculty who want to change but need guidance and inspiration on how to begin.

As legal education considers the wisdom in revising our accreditation standards, and as we enjoy our summer of writing and preparing for fall classes, I would ask that we consider the next steps towards diversifying our curricula and fixing the disconnect between our teaching and our institutional goals. Let this be the summer of reviewing LSSSE data, auditing our syllabi for diverse voices, supplementing our casebooks with readings that seek to decolonize the law, re-considering our pedagogical practices, and making room for the lived experiences of our students in our classrooms.