Guest Post: Bridging Global Divides in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: Bridging Global Divides in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: Bridging Global Divides in Law School and Beyond

Shruti Rana

Professor International Law Practice

Assistant Dean of Curricular and Undergraduate Affairs

Director of the International Law and Institutions Program

Hamilton Lugar School of Global & International Studies

Indiana University Bloomington

International law is a growing and dynamic field, offering students a launching pad into a variety of careers spanning sectors from government to private practice to non-profit or advocacy work. Lawyers and advisors trained in international law have opportunities to address some of the most pressing global challenges of our time, and to build bridges through trade, business, migration, communications or capacity-building work. Careers in this field can be groundbreaking and even glamorous—notable international lawyers include Amal Clooney, Shirin Abadi, and Samantha Power.

Not surprisingly, then, international law is a popular choice for students entering law school—1L students rank international law as one of their top 10 areas of intended specialization. However, as they progress through law school, students’ interest in international careers drops steadily over time, and by graduation, international law drops down to sixteenth place in terms of student interest. These drops are especially striking for women and students of color, who initially show more interest in international law than other students yet appear similarly disillusioned by law school’s end. These trends are even more alarming for the legal profession and our nation as a whole when we consider that although “decades of research and experience prove that diversity strengthens decision-making, promotes innovation, and brings new, critical perspectives to global challenges,” women and people of color are greatly underrepresented in these global careers.

The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) offers some intriguing data on the question of why U.S. law students turn away from international law over time. The data also provide clues as to where the key gaps in U.S. legal education are with respect to international law, and the impact of these gaps on students’ inclusion and opportunities in law school and beyond. They offer an important starting point for leaders in legal education to consider in developing programs and perspectives that cultivate and support students interested in careers in international law. Ultimately, addressing these gaps can help create more inclusive environments for all students, as well as foster the development of the global competency skills that are increasingly critical for any legal career.

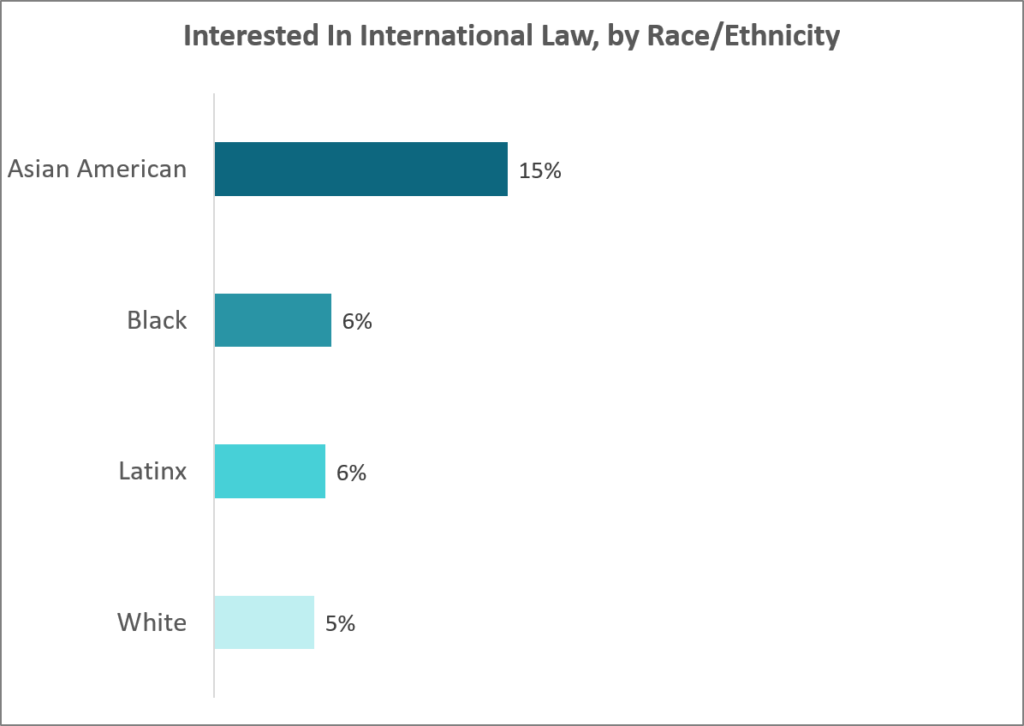

Beginning with the students themselves, LSSSE data show that students who express interest in and stick with international law as a career choice differ in striking ways from students who do neither. In terms of student diversity, there is a marked gender divide in interest in international law, with women comprising 64.8% of the students interested in pursuing international law. Overall, 7% of the women entering law school are interested in international law as compared to 5% of men. Students interested in international law are also more diverse in terms of race and ethnicity than students who are not, with Asian American students in particular significantly more interested in international law.

Students interested in international law are often advised to look outside of law school to develop the language, policymaking, and cultural competence skills they will need to understand the mechanisms of global governance and operate in diverse global environments. LSSSE’s data show that students interested in international law do just that. While in law school, students interested in international law are more than three times more likely to pursue a joint LLM or MA degree than students not interested in international law, perhaps to obtain global skills not traditionally taught in J.D. programs (34.8% of students interested in international law are pursuing a JD/MA, and 27.0% are pursuing a JD/LLM as opposed to 9.3% and 9.8%, respectively, of students not interested in international law). However, students who are interested in international law are about a third to one-half less likely than law students as a whole to pursue joint MBA or MS degrees. (13.5% of interested students pursue joint MBA degrees compared to 31.7% of non-interested students, and pursue MS degrees at roughly half the rate (4.5%) of students not interested in international law (8.1%). Perhaps because they must look elsewhere to develop the skills critical to international careers, students who express an interest in specializing in international law are also somewhat less satisfied with their law school experiences, as they are more likely to say that if they could start over again, they would probably not choose to attend the same law school they are now attending (18.6% of students interested in international law compared to 13.8% of students not interested in international law).

Looking beyond their law school experiences, students who express an interest in international law also show significantly different workplace preferences. As compared to students who do not express an interest in international law, they show a greater preference for government positions (15.6% vs. 10.5%), public interest groups (9.1% vs. 5.5%) and large firms over small (19.8% vs. 14.2%). They are also less interested in domestic criminal law (only 3.3% are interested working as prosecutors or public defenders, as compared to nearly 10% of students not interested in specializing in international law).

The differences delineated above correlate with and parallel larger trends in the fields of international law and global affairs. Although women make up an increasing percentage of students pursuing college and graduate education in law and the humanities, they are greatly underrepresented in professional careers in the international arena, where their perspectives and experiences are often devalued and marginalized. (See, e.g., Women in International Relations, Politics and Gender 4(1)(2008), and Do Women Matter to National Security? discussing survey results revealing the lack of women in leadership roles in these areas and in the priorities of these fields); see also The Emotional Labor of Teaching—A Feminist Critique of Teaching International Law discussing the marginalization of feminist perspectives in international law). It is likely that women both encounter these barriers to entry and general hostility to women in international affairs and institutions while in law school, and that these barriers are compounded by a lack of available mentors and visible representation in the field. The gendered impacts of these divisions are further amplified and mirrored when race, ethnicity, and the hierarchical and historical legacies of our current system of international law are added into the mix. The challenges of grappling with the colonial legacies of the current international order, or of addressing inequality through and within the field of international law, add to the already significant challenges of international careers.

It is likely that students begin (or continue) to encounter these perspectives and obstacles in law school, as international law and the language and cultural skills needed to pursue global careers are often marginalized within the legal academy. This marginalization is reflected in teaching and scholarship, the often negative perceptions of international LLM students in U.S. law schools (which LSSSE data has helped refute), and the contrasts with law schools outside of the U.S., where international law is usually a required subject. The international law arena is replete with the stories of people drawn to the field because of their experiences in the liminal, transformative spaces or social justice movements created in the wake of migration, development, war or the many other forms of global inequality—only to run directly into brick walls in law school when they encounter international law as “a discipline and a language that genuflects before the status quo” in ways that appear irreconcilable with goals such as addressing the causes and impacts of global inequality. Law schools, it appears, replicate rather than reduce the dynamics of inequality that first draw diverse students to law school, which then push them away from their careers of choice and the fields where diverse perspectives are so urgently needed.

The LSSSE data provide a valuable starting point for thinking about how we can continue to address the marginalization of international law in U.S. law schools, and its implications for students interested in international careers. We must support students in building global competency skills and the networks they need to break professional barriers, and foster an environment that equips them not to shackle but unleash the liberatory power of the law. At Indiana University, we have begun to take a number of innovative steps to address such obstacles, and create an inclusive environment focusing on the development of global skills to prepare students for careers in international law and global affairs. Our International Law and Institutions program, a joint endeavor between the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and the Maurer School of Law, focuses on the hard and soft skills students need to pursue careers in international law and global affairs. These programs include intensive language training combined with in-depth regional experience and a focus on gaining a holistic understanding of the tools and mechanisms of global governance and civic leadership. They also include initiatives aimed at enhancing the diversity of the field of global affairs and providing the mentorship, training and networks students need to succeed in these careers. As the global challenges we face intensify and multiply, these and other efforts to enhance and prioritize the skills and experiences our students need to be “globally ready” can help build the foundations for a more inclusive and equal future.

Student Debt is a raceXgender Issue

Student Debt is a raceXgender Issue

Student Debt is a raceXgender Issue

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement

William H Neukom Chair in Diversity & Law, American Bar Foundation

Previous LSSSE publications have highlighted how the escalating costs of law school attendance have changed the landscape of legal education. Our 2020 Retrospective Report (which analyzed fifteen years of data) revealed that while in 2004, only 18% of LSSSE participants expected to owe over $100,000, by 2019 that number had skyrocketed to 39%. In 2015, LSSSE published an Annual Report stating that “the large racial and ethnic wealth disparities in the U.S. have broad implications on student debt trends,” with students of color carrying greater debt burdens than white classmates. More recently, in a publication entitled The Cost of Women’s Success, we found that women are more likely than men to borrow at the highest levels to earn a law degree—with 19% of women owing over $160,000 and 7.9% owing over $200,000 (compared to 14% and 5.5% of men, respectively).

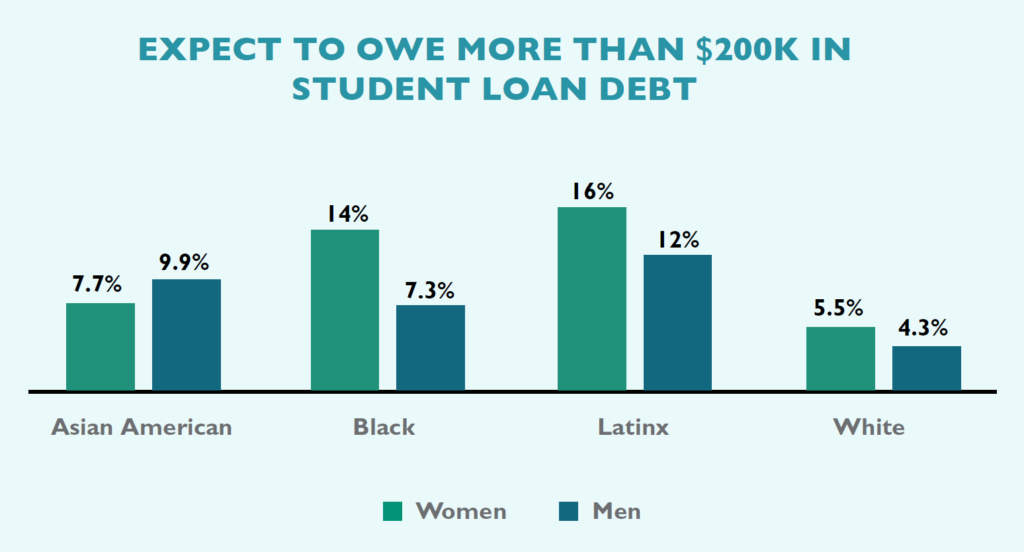

Given the increasing costs of legal education overall, as well as ongoing gender disparities and racial/ethnic disparities, it should be no surprise that there are also marked raceXgender disparities. My previous research has introduced the concept of raceXgender bias, explaining “how the combination of these two particular identity characteristics create not just additive but compound effects in the personal and professional lives of women of color.” Applying that intersectional framework to the context of student debt, it becomes clear that we must think of increasing student loans as a raceXgender issue.

Not only do women as a whole carry greater debt burdens than men, but these gender disparities remain constant within every racial/ethnic group. In other words, women of color shoulder a disproportionate share of the debt burden in legal education. A full 16% of Latinas and 14% of Black women expect to graduate with more than $200,000 in student loans, compared to 12% of Latino men, 7.3% of Black men, and smaller percentages of those from other racial/ethnic groups. No Native American respondents expect to owe over $200,000 to complete their education; however, consistent with gender disparities in other racial/ethnic groups, a full 15% of Native American women carry over $160,000 in student loans, compared to just 7.1% of Native American men.

Legal education must address student loan disparities—not only as a racial justice issue, not only as a critical women’s issue, but also as an issue of raceXgender bias.