Guest Post: A Message to White Law Faculty: Mentor Racial Minority Students

Guest Post: A Message to White Law Faculty: Mentor Racial Minority Students

Guest Post: A Message to White Law Faculty: Mentor Racial Minority Students

Gregory S. Parks

Associate Dean of Strategic Initiatives and Professor of Law

Wake Forest University School of Law

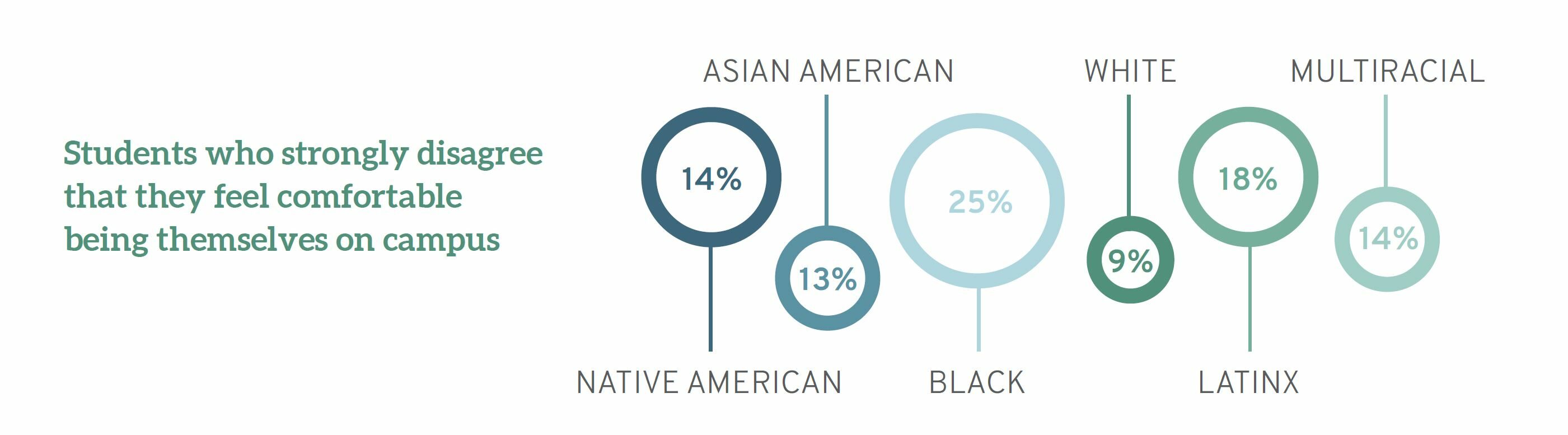

Pursuant to Law School Survey of Student Engagement’s (“LSSSE”) 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Annual Survey, there are troubling findings with regard to racial minority students’ sense of belonging and institutional support. Thirty-one percent of White students, but only 21% of Black and Native American students, feel a part of their law school community. Moreover, “women of color are more likely than men from same ethnic/racial backgrounds to feel that they are not part of the campus community.” Specifically, 34% of Black women law students felt this way. When asked if they did not feel comfortable being themselves on campus, 12% of White students agreed compared to 21% of Black, Latinx, and Native American students. Students of color are more likely to believe that their school does “very little” to ensure they are not stigmatized based on identity characteristics. Twenty-five percent of Black, 18% of Latinx, and 14% of Native American students—compared to 9% of White students—agree with the statement.

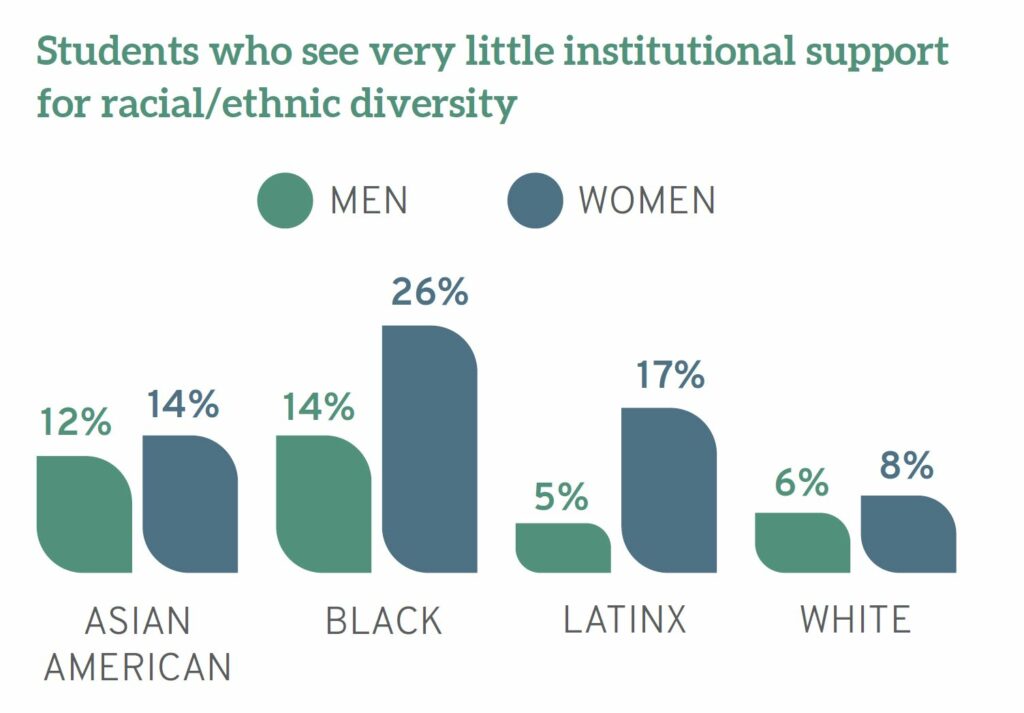

When it comes to perceptions of institutional support, 32% of White students believe that their school does “very much” to support diversity compared to 18% of Black students. Correspondingly, 26% of Black women, 14% of Black men, 8% of White women, and 6% of White men believe that their school is doing “very little” to create an environment to support diversity. In addition, 28% of White students feel like their school does “very much” to support community among students while 18% of Black students and 14% of Latinx think their school does “very little.” Not surprisingly, only 31% of Black men, 18% of Black women, 32% of Latinx men, 23% of Latinx women, 31% of White men, 26% of White women, 25% of Asian American men, 23% of Asian American women, 27% multi-racial men, and 23% multi-racial women strongly agree that they feel valued by their institution.

Faculty of color often shoulder a disproportionate amount of emotional labor in supporting students of color.[1] As such, White law faculty can and should play a meaningful role in making the law school experience one where racial minority law students feel a greater sense of belonging and institutional support. That is through mentoring. Mentoring has two distinct functions—professional and psychological. Professional mentoring aids the mentee in advancing in the workplace. Psychological mentoring seeks to bolster the mentee’s competence, effectiveness, and identity. Mentoring relationships are rooted in clear expectations, mutual respect, personal connection, reciprocity, and shared values. Within the context of cross-racial mentoring relationships, mentors must be proactive in building a foundation of mutual respect and trust. In doing so, the mentor must develop cultural awareness and sensitivity to cross-cultural issues.

As such, mentors must:

- Recognize their own privilege.

- Have a growth-mindset in the relationship.

- Empathize with their mentee where possible.

- Listen to understand when they cannot.

- Guide the mentee to their own fullest potential.

- Diversify their own viewpoints and knowledge to become more informed on issues that may not affect them.

It takes work to be a good mentor. But it pays dividends for the mentee, mentor, institution, and legal profession. Law faculty have a lot on their plate. And while it is unreasonable to think that law faculty, in the aggregate, can mentor every law student at their school, the truth is that we can likely do much better than we are doing. And given that racial minority law faculty often carry much of the emotional labor associated with supporting the most marginalized law students, White colleges can and should play a much more significant role in this effort.

___

[1] See Meera E. Deo, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia (2019)(note chapters 3 and 4).

Knowledge, Skills, and Personal Development in Law School

What does one learn in law school? In this post, we describe the areas of academic, professional, and personal development that graduating law students feel were most strongly influenced by their law school experience.

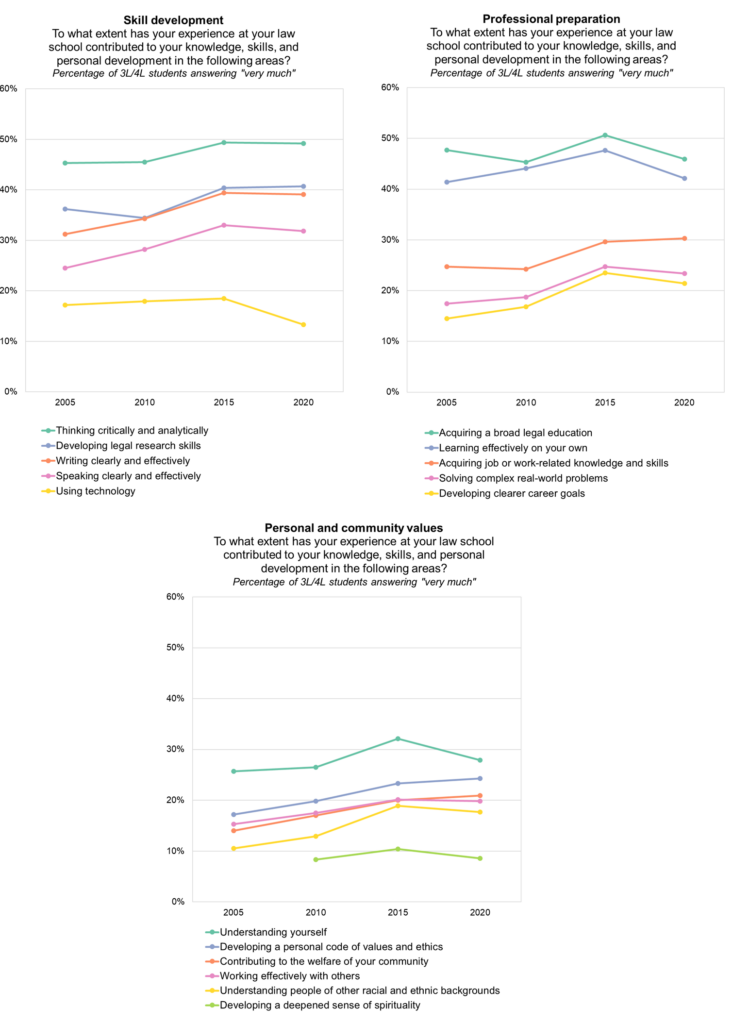

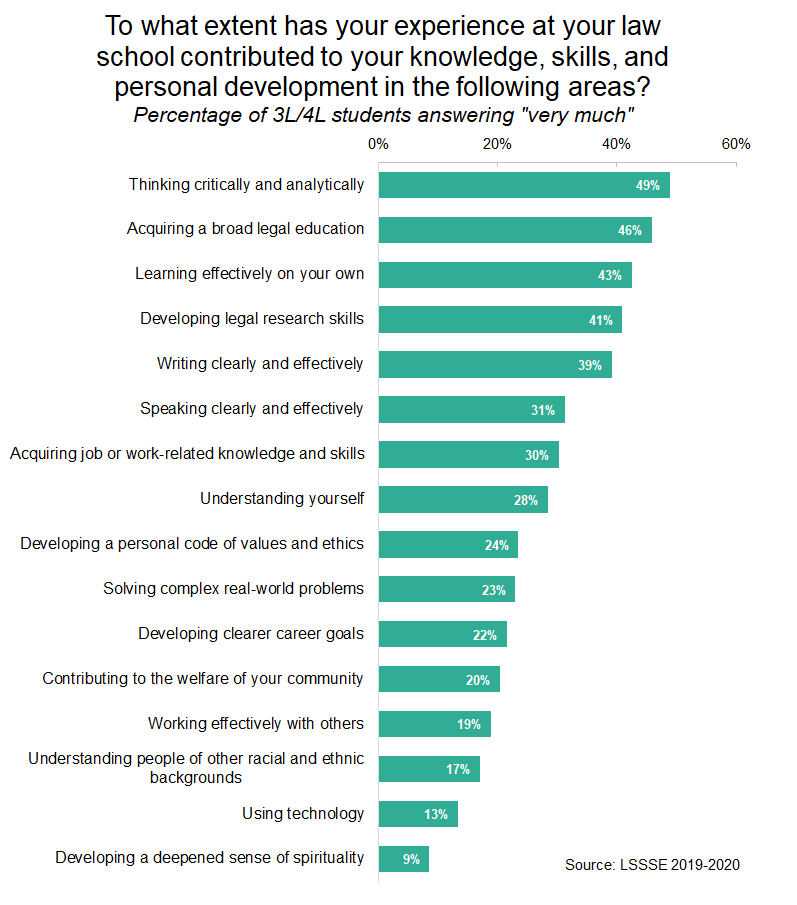

Students nearing graduation (full-time 3L students and part-time 4L students) in 2020 were most likely to say that they developed “very much” in terms of their ability to think critically and analytically (49%) and in acquiring a broad legal education (46%). Research, writing, and speaking skills were also key areas of academic and personal growth. Fewer students responded that they developed “very much” in interpersonal skills such as working effectively with others (19%) and understanding people who are different from themselves (17%).

From 2005 to the present, graduating law students have been remarkably consistent in the areas in which they say they have developed the most. Between 40% and 50% of law students over the last fifteen years feel they have acquired a broad legal education and learned how to learn effectively on their own. However, only around 20% of law students felt they had learned very much both about solving complex real-world problems and about developing clearer career goals, although these numbers have climbed over time. In terms of personal development and community values, usually about three in ten graduating students say they have made “very much” progress in understanding themselves, but only between 10% and 20% of students have made similar gains in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. However, this area of interpersonal development has also increased noticeably over the last fifteen years.