Online Learning and Law Student Age

The 2020-2021 academic year was unlike any other, forcing students and instructors to adapt to a different way of living and learning. Prior to the pandemic, law schools were less likely than other sectors of academia to embrace online learning. But when it became clear that COVID was not going away, many law schools shifted to primarily online interactions. The Online Learning module, which debuted with the spring 2021 LSSSE survey administration, was developed to capture students’ perceptions and experiences with online classes during this peculiar academic year and potentially beyond. Although the abruptness of the transition to online learning and the external stressors inherent to pandemic life may make these data unique in some ways, in other ways they are an excellent starting point for law schools to learn about how to structure their curriculum to leverage the strengths of the online environment, even as traditional in-person learning resumes.

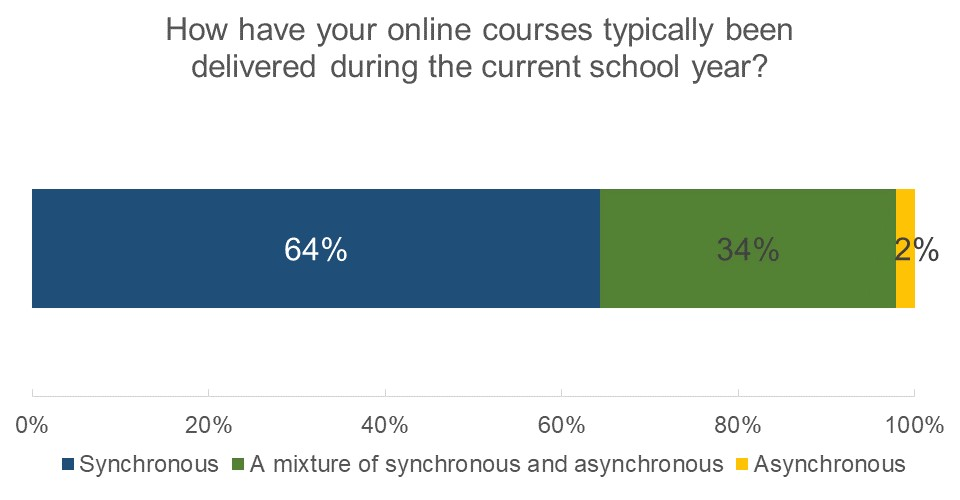

What types of online learning experiences were law students having in 2020-2021? Nearly all students who took online courses had at least some synchronous element in their courses. Nearly two-thirds of students typically had synchronous courses while another third experienced a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous content. Only about two percent of students typically received only asynchronous content.

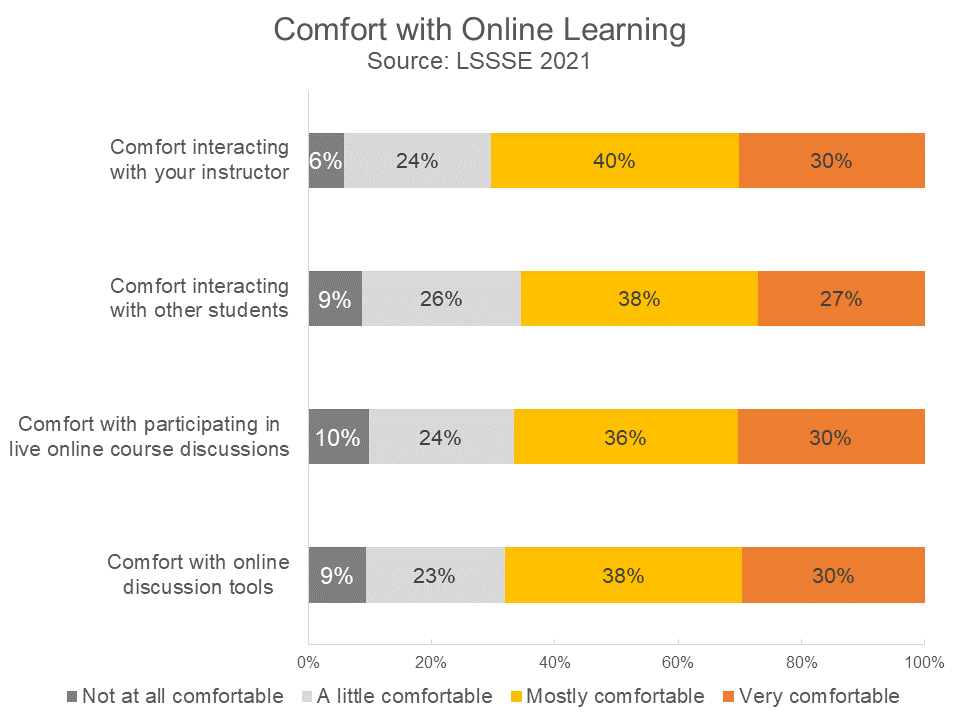

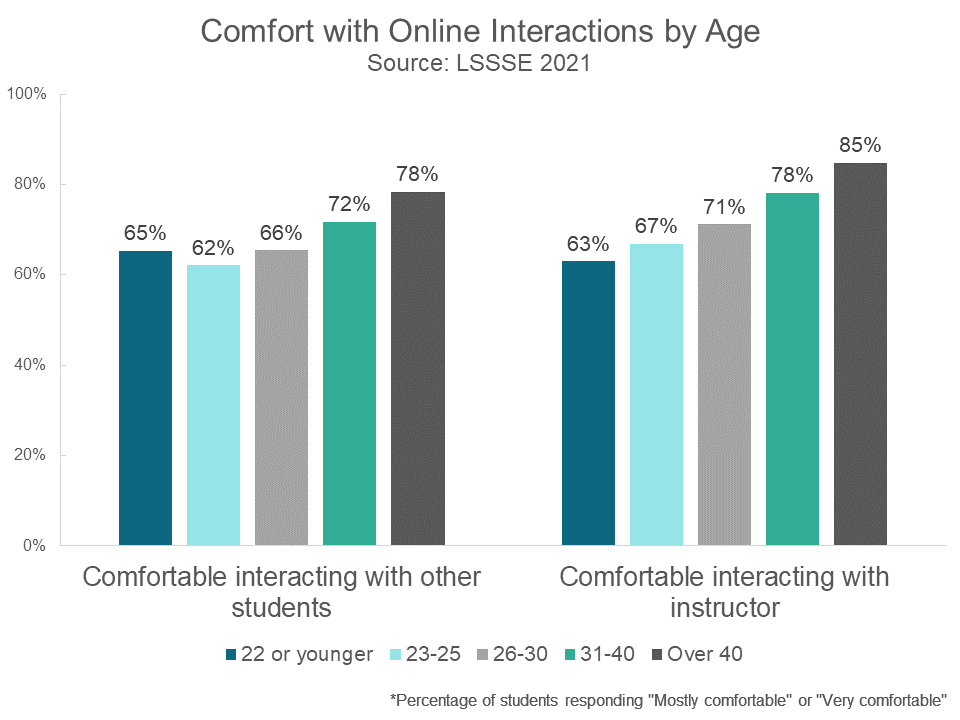

Most law students were fairly comfortable with online learning. Seventy percent of students were mostly comfortable or very comfortable interacting with the instructor of their online courses, and around 65% felt similarly about interacting with the other students. About two-thirds of students were comfortable with online discussion tools such as discussion boards and forums and about two-thirds of students were comfortable with live online course discussions.

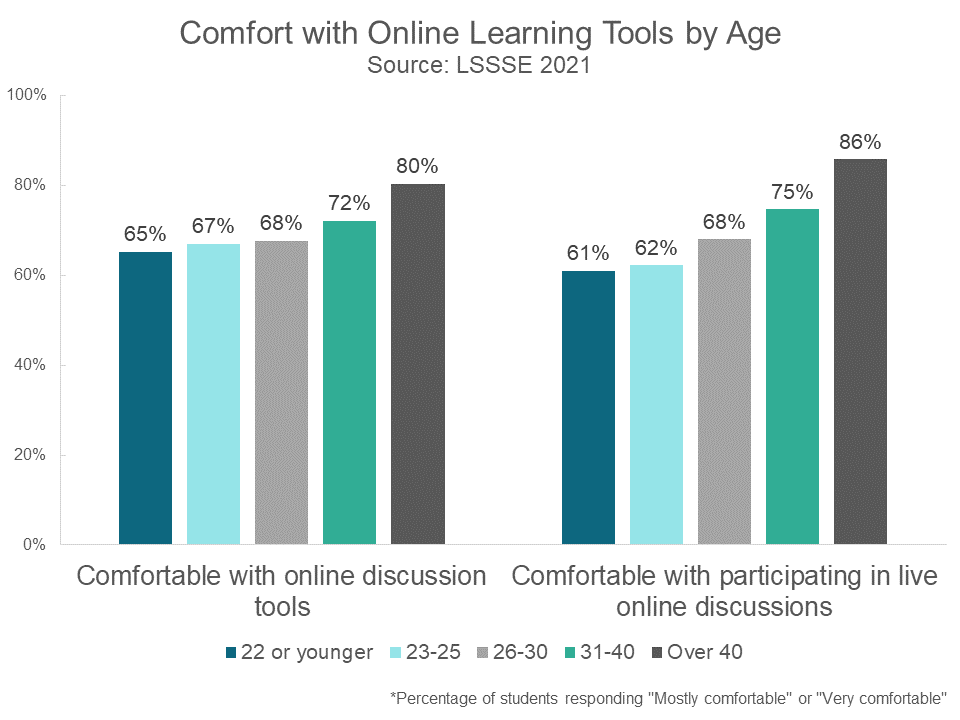

Interestingly, older students were more likely to be comfortable with virtually all aspects of online learning relative to their younger peers. In fact, comfort with online learning tools increased steadily across age brackets. The vast majority (86%) of students over 40 were comfortable participating in live online discussions compared to only around 62% of students 25 or younger.

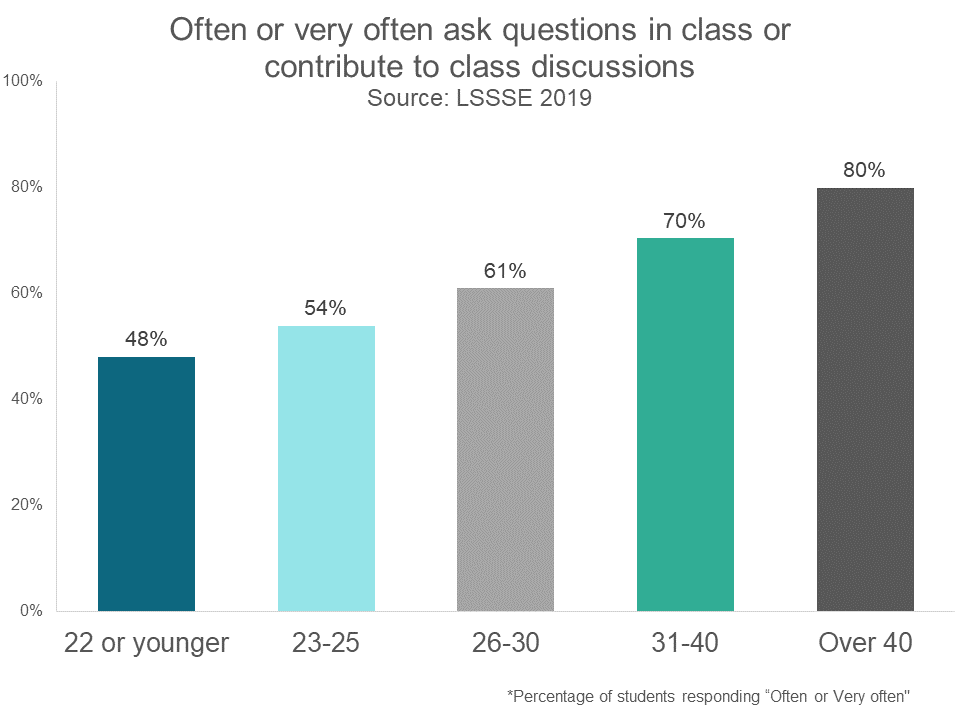

This age discrepancy in participation exists in physical classrooms too. In 2019, before the widespread adoption of online law classes, 80% of students over age 40 often or very often asked questions in class or contributed to class discussions, compared to 48% of those 22 or younger and 54% of those between 23 and 25. In fact, students under age 30 may be somewhat more comfortable with online course discussions than in-person ones, even though their overall participation is less than that of their older classmates regardless of the class setting.

Older students were also more likely to be comfortable interacting with their peers and instructors online. Only 63% of students age 22 or younger were comfortable interacting with their instructors online, compared to a full 85% of students over 40. Among students between the ages of 23 and 25 (the most common age for a law student), less than two-thirds were comfortable interacting with other students in their online classes, compared to a full 78% of students over 40.

Although popular media tends to suggest that younger people are more adept with technology, the oldest Millennials – the first generation to live much of their lives online – are now in their forties. Perhaps these older students have adapted to so much online technology across their personal and professional lives that another pivot was not as disruptive as it was for their younger colleagues. Regardless of the reason, the LSSSE data show clearly that law schools should make a deliberate effort to support the technological skills and online engagement levels of their youngest students.

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Jonathan Todres

Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law

Georgia State University College of Law

An unhealthy work-life balance is an all-too-familiar phenomenon in law school, as well as for the legal profession. Mental health and substance use issues have been well-documented in the profession, and a breadth of research shows the detrimental effects of law school on many students’ well-being. All that was true before the COVID-19 pandemic inflicted its double burden—increasing the number of students who are suffering, and exacerbating the extent of harm experienced by those who were already struggling. Of course, there are many underlying causes that demand urgent attention, but an often-overlooked issue is the nonstop work culture of law school that discourages students from taking any time off.

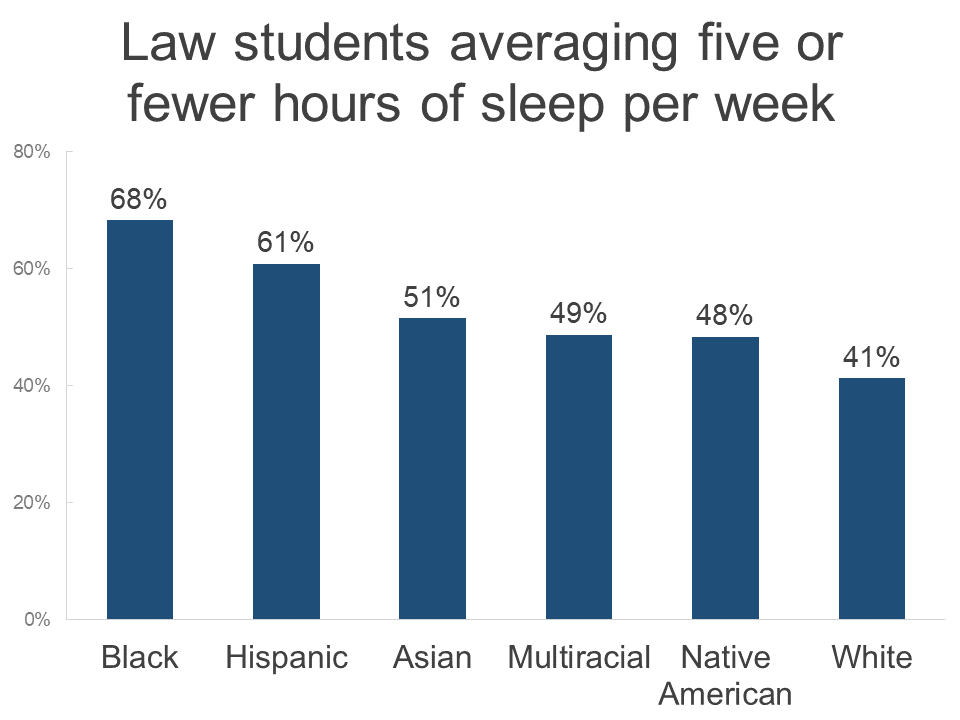

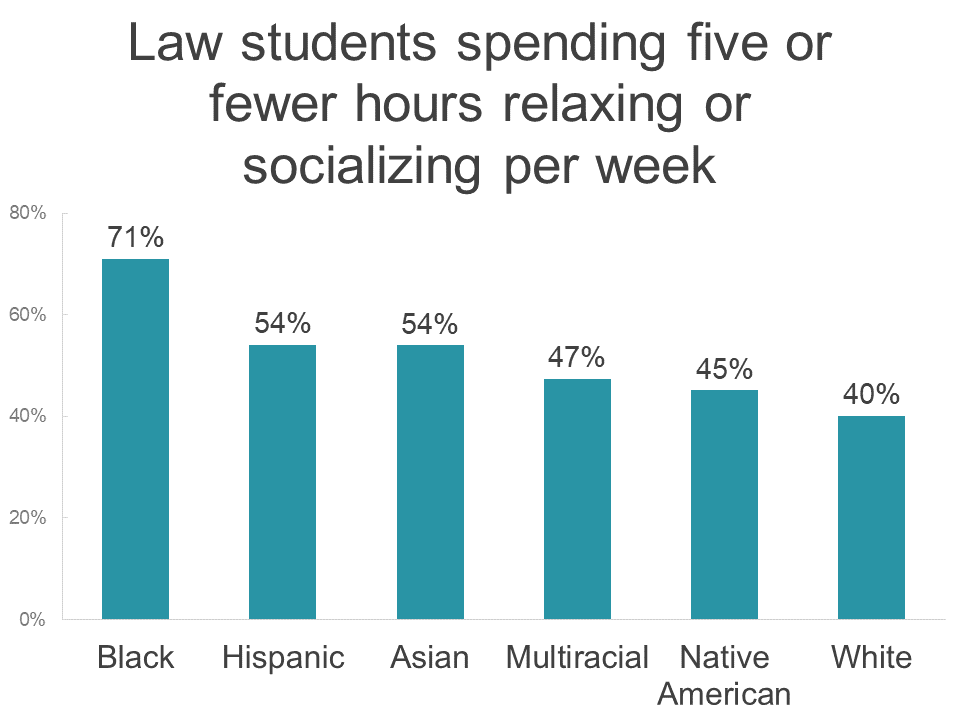

Students need a break. In the 2021 survey administration of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement, nearly half of law students reported averaging five or fewer hours of sleep per night (including weekends). In addition, 43.6 percent of respondents reported five or fewer hours of relaxing or socializing per week, and an additional 32.1 percent reported only 6-10 hours of relaxing or socializing per week. Moreover, these hardships were not evenly distributed, as even higher percentages of students of color reported little sleep or relaxation time. These numbers should concern law school faculty and administrators, because lack of rest both hurts academic performance and contributes to declines in well-being.

If law students are going to achieve and maintain a healthy work-life balance, law schools cannot simply tell students to take care of themselves. Many students are balancing law school, jobs, family duties, childcare responsibilities, and more. This will be true even after the pandemic ends. “Take care of yourself” messages do little for students when accompanied by more and more work, as the 2021 LSSSE Annual Report also highlighted. Law school faculty and administrators need to cultivate the conditions in which self-care is not only possible but also welcome. A key component of that includes enabling students to take time off.

Last spring, I tried to do just that. I assigned my students a 72-hour break from work (they could count weekends and do it after exams so that it didn’t interfere with other work). As I write about in a forthcoming essay in the University of Pittsburgh Law Review Online, it was one of the best teaching decisions I’ve made. Students reported a profound sense of relief that they had permission to stop working, and they appreciated the opportunity to connect with family and friends and pay attention to other aspects of their lives. It bears noting that they also reported feeling guilty for not working. Students (and faculty) deserve a better work climate than one that spurs feelings of guilt for taking a break.

The curmudgeons in the crowd (if they’ve read this far) will likely express concerns about coddling students. My students had already worked hard. They had earned it, but more important, they needed it. Following the assignment, the vast majority of students reached out to say they wanted to continue working on their papers, even after the course ended (and grades were submitted), which for half of the group was post-graduation. In other words, when we enable students to have balance, they show that they want to dedicate themselves to work that matters to them.

The nonstop work culture of law school is not limited to students. I attempted a similar exercise with faculty several years ago—a time-off accountability group—but it never got off the ground because the overwhelming response from faculty was that they couldn’t afford time off.

Changing the culture of the law school is a major undertaking. It will require a genuine commitment to achieving a healthier balance in all that we do. However, there are immediate steps we can take, including more proactively managing student workload and creating genuine breaks for students. Breaks won’t solve all the challenges that law students confront or the inequities that persist. But they will allow students more time for family, friends, and self-care. Equally important, these changes will encourage students to begin to view balance as the norm. Supporting students and enabling them to develop better life-work balance can help them achieve more well-rounded lives and reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes. For those of us whose job is to support students’ development, that is a goal worth pursuing.

Ivermectin - COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines: https://www.cpgh.org/ivermectin/.