Learning Effectively on Your Own

Working independently and working collaboratively are both important skills for budding legal professionals. In addition to learning through classroom experiences, law students must assume responsibility for learning large amounts of material in a relatively short period of time, often independently and sometimes in small groups. We examined the extent to which law students feel that their experiences in law school have contributed to their personal development in both learning effectively on their own and working effectively with others.

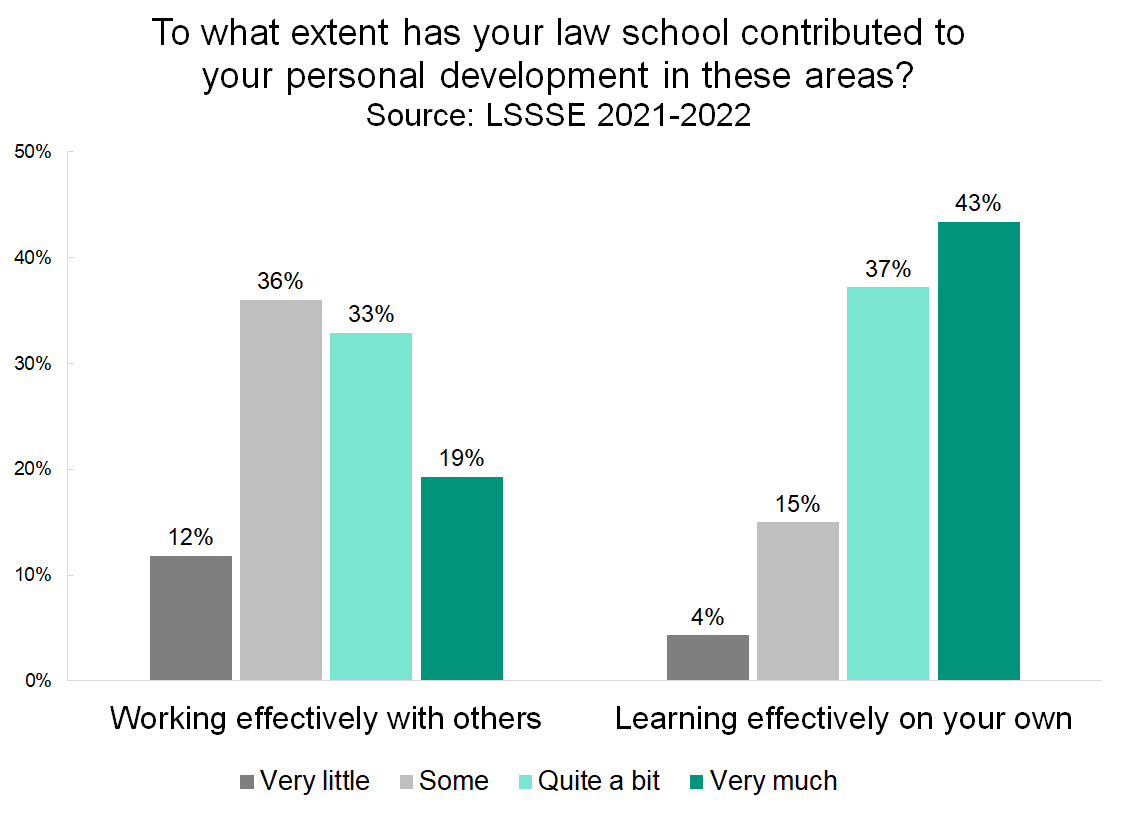

Four in five law students say that law school helped them “quite a bit” or “very much” in developing the ability to learn effectively on their own. Fifteen percent say that they developed “some” skills in this area, and only four percent said they developed “very little.” By comparison, only about half (52%) of law students learned “quite a bit” or “very much” about working effectively with others. A little more than a third (36%) developed “some” skills in this area, and more than one in ten (12%) learned very little about working effectively with others.

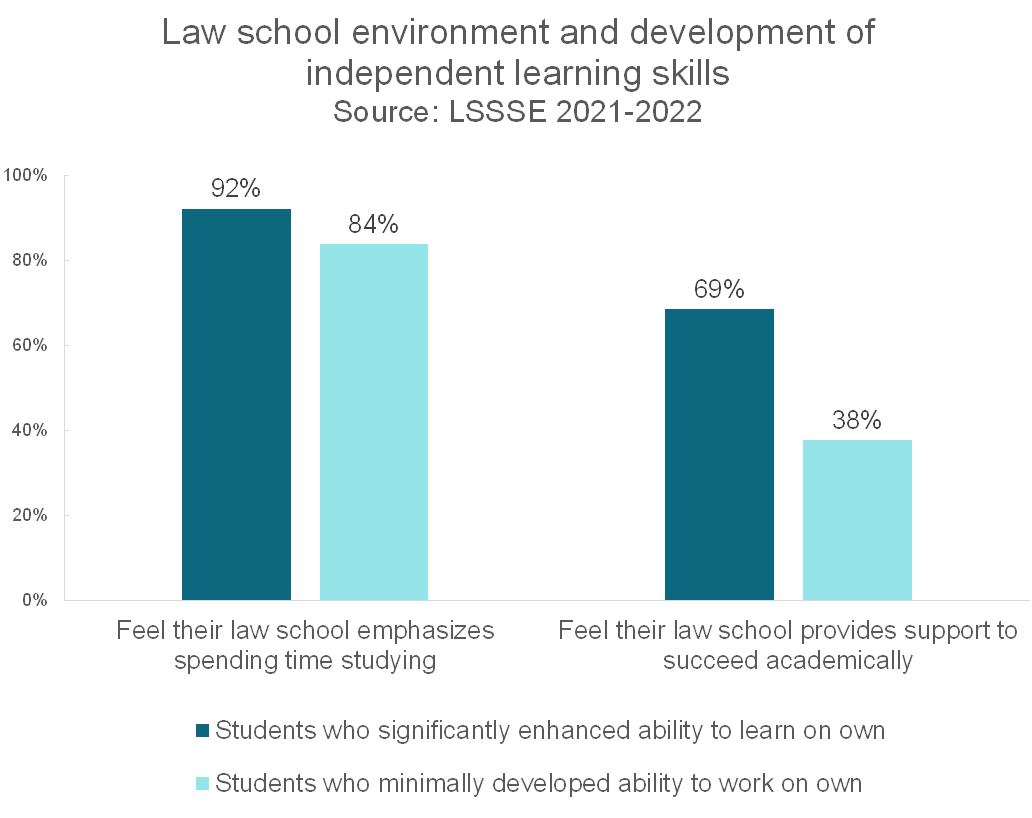

Students who greatly enhanced their ability to work on their own generally feel both that their law school has high standards and that their law school adequately supports their academic endeavors. Nearly all (92%) of students who significantly enhanced their independent learning skills felt that their law school emphasizes spending significant amounts of time studying and on academic work compared to 84% of their colleagues who developed fewer skills in this area. Additionally, over two-thirds (69%) of students who honed their ability to learn independently felt that their law school provides the support they need to succeed academically compared to only 38% of their peers. Rigor and institutional support work together to drive student achievement.

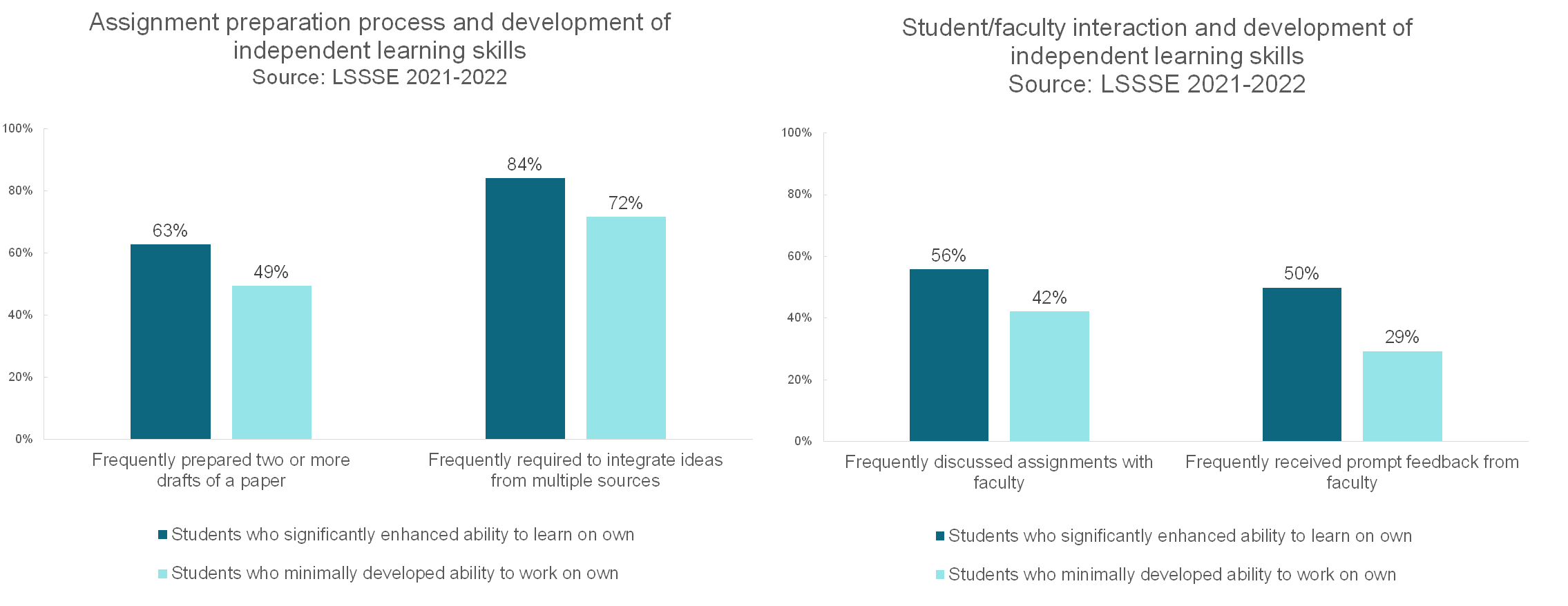

Students who substantially enhanced their ability to learn independently were more likely to revise course assignments at least once and to engage more deeply with course content. Sixty-three percent of independent learners frequently prepared two or more drafts of a paper or assignment and 84% were frequently required to integrate ideas from multiple sources in papers or course assignments. Students who developed independent learning skills were more likely to frequently discuss assignments with faculty compared to students who developed less of an ability to learn independently. Perhaps crucially, the independent learners were more likely to frequently receive prompt feedback from faculty (50% received prompt feedback "often" or "very often") compared to law students with less-developed independent learning skills (29% received prompt feedback "often" or "very often"). Deep, sustained learning is often an iterative process that requires feedback from experts, and this is borne out by the LSSSE data.

Next month we will look at how students who feel law school has contributed substantially to their ability to work effectively with others differ from those students who do not feel this way. We will also consider how interpersonal effectiveness skills might affect attitudes toward diversity.

Law School Support for Non-Academic Responsibilities

Law students vary in their amount and type of non-academic responsibilities, and they also vary in the degree to which they feel that their law school helps them cope with these responsibilities. In addition to their studies, some law students work, care for children or other dependents, and engage in community activities. We wanted to examine the degree to which students feel supported in these endeavors by their law schools.

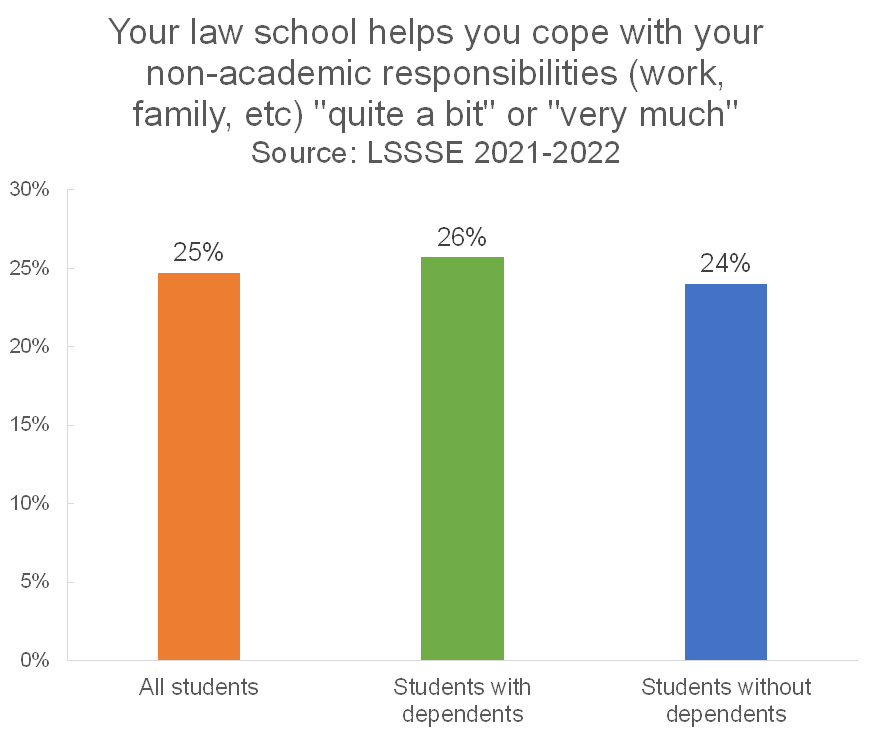

Time Spent Caring for Dependents

Thirty-eight percent of law students spend at least one hour per week caring for dependents living with them (parents, children, spouse, etc.). Interestingly, there is little difference in the percentage of students with and without dependent care duties who feel that their law school emphasizes helping them cope with their non-academic responsibilities. About a quarter of each group (26% of students with dependents and 24% of students without dependents) feel well-supported. However, students with dependents are slightly more likely to say that their law school does very little to help them cope with non-academic responsibilities. Two out of five (42%) of students with dependents feel this way compared to 38% of students without dependents.

Gender and Dependent Care

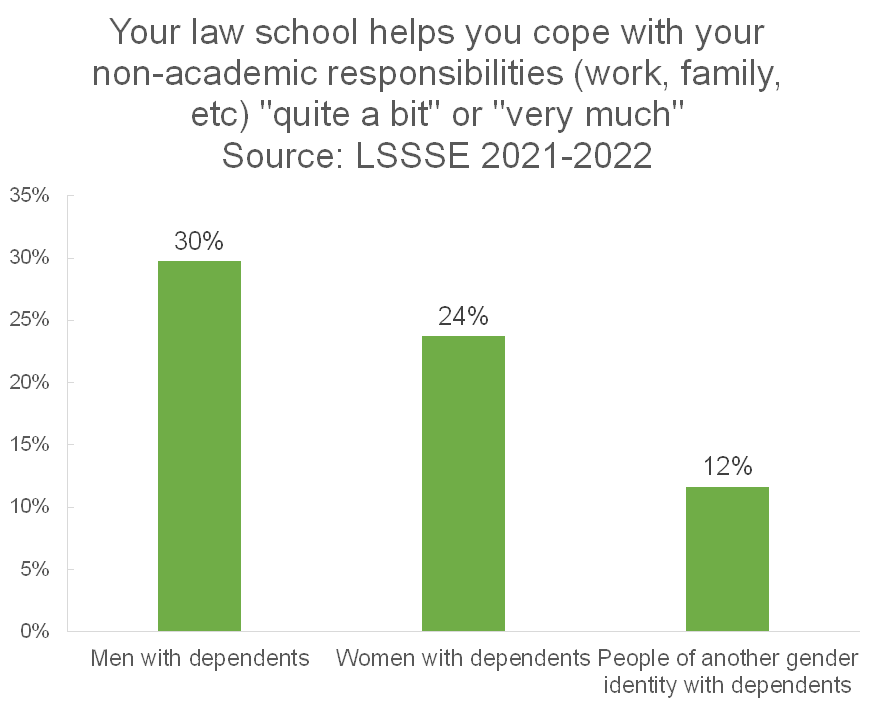

However, there are huge differences by gender. Men with dependent care responsibilities are much more likely to feel supported by their law schools than women with dependent care responsibilities, and both groups feel more supported than people of other gender identities with dependent care responsibilities.

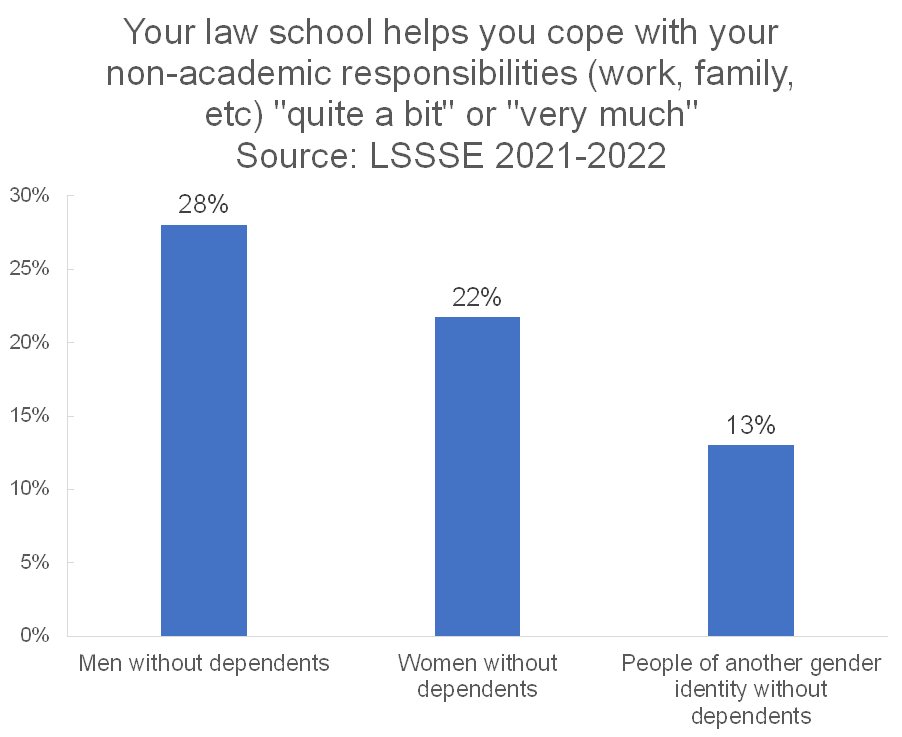

It appears, however, that this effect is more about gender and less about the dependent care responsibilities as we see this same disparity across gender among people without dependent care responsibilities.

Time Spent Working for Pay

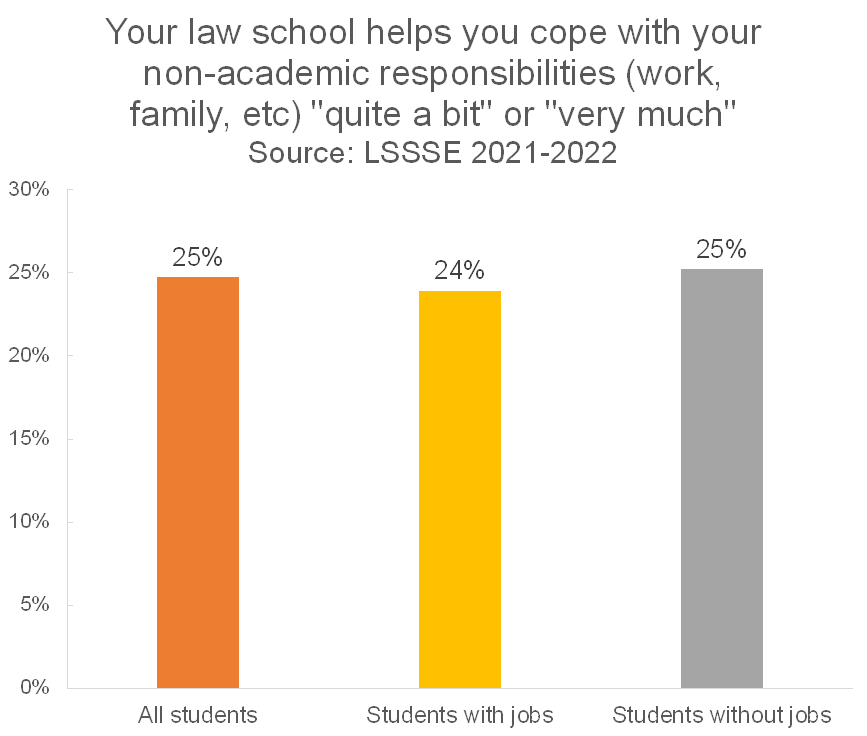

Similar to the pattern we see with dependent care duties, there is minimal difference in the perceived level of support for non-academic responsibilities between students who have jobs and students who do not. Around one in four students in either category say that their law school emphasizes supporting their non-academic responsibilities.

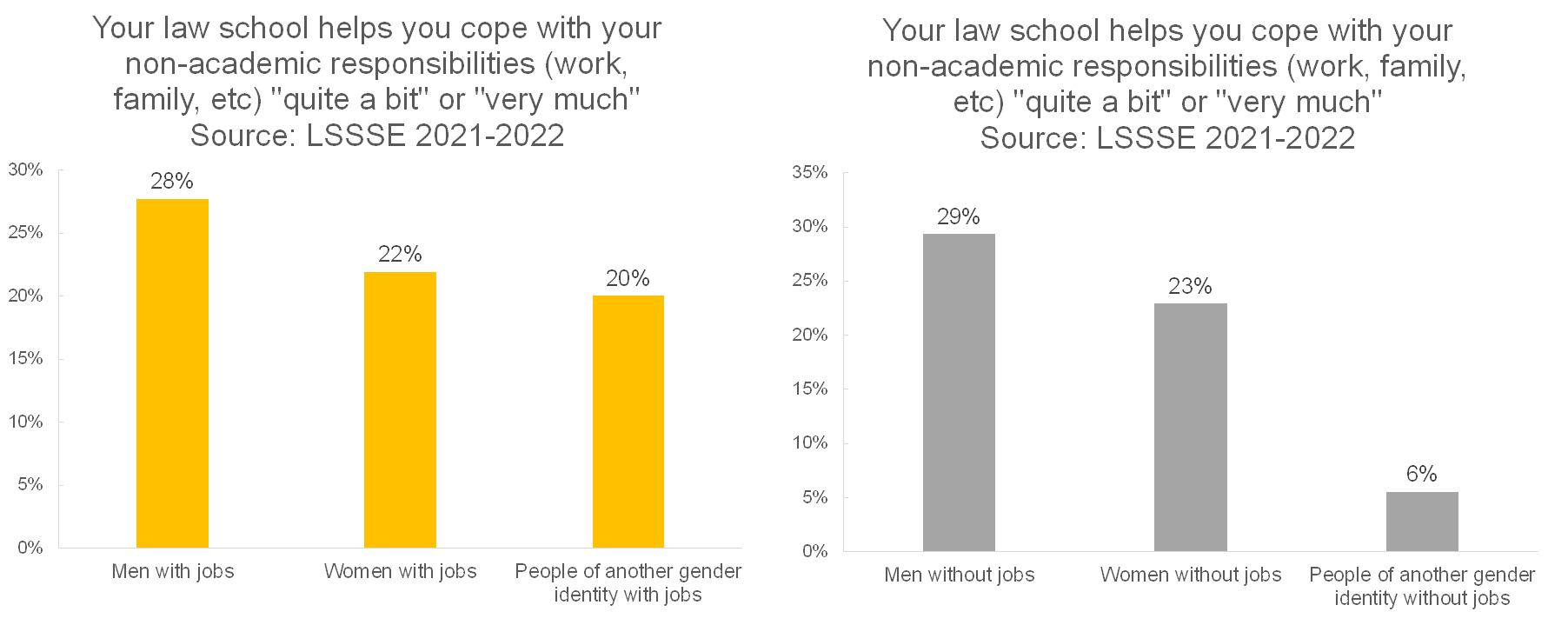

Gender and Employment

The gender pattern for perceived support is much the same for working/non-working students as it is for dependent care duties. Men are more likely to feel high levels of support than other students. However, people who identify as neither men nor women are actually more likely to feel highly supported in their non-academic responsibilities when they are employed (20% of students) relative to when they are not (6% of students).

Regardless of how they spend their time outside of law school, men are much more likely to feel highly supported in their non-academic responsibilities, people of another gender identity are very unlikely to feel supported, and women generally fall somewhere in between. Adequate support for non-academic responsibilities clearly looks different for different people, and it appears that gender is a major factor. Rather than focusing on student populations based on which responsibilities they have and how they spend their time outside of the classroom, law schools may want to consider the unique needs of women and people of other gender identities to close the gap in the degree of support they feel about coping with their non-academic responsibilities.

Part 2: Part-Time Students & the Law School Experience

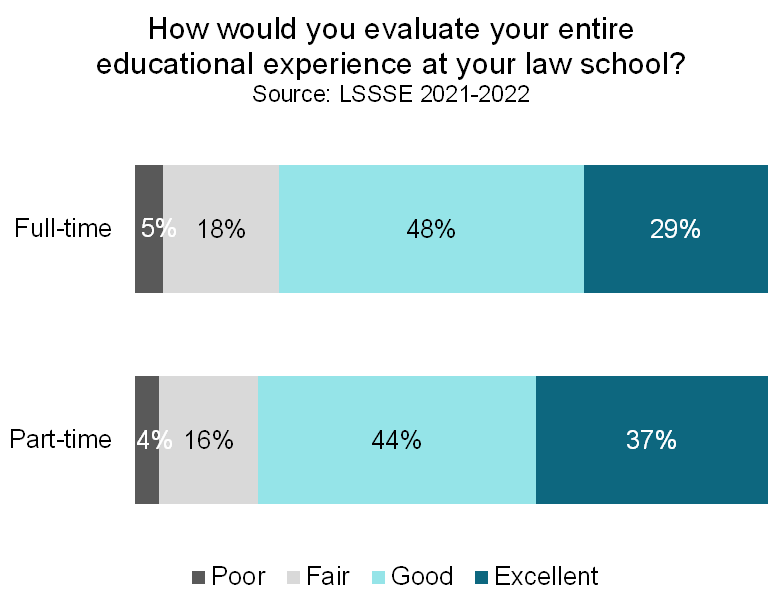

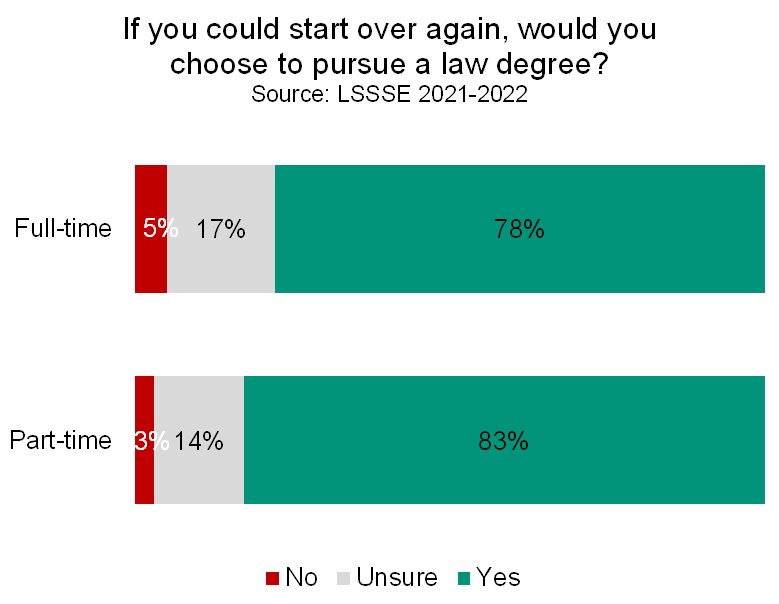

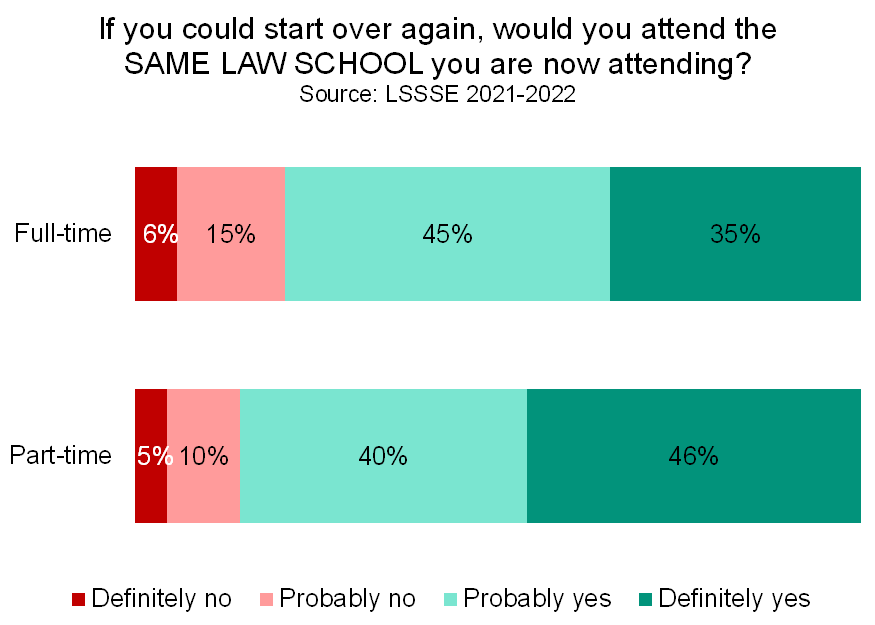

Part-time law students tend to be particularly happy law students. Four out of five part-time students (81%) rate their overall law school experience as good or excellent compared to 77% of full-time students. In fact, 37% of part-time students give their school an excellent rating compared to just 29% of full-time students. Most part-time students (83%) would choose to attend law school again if they could start over, and a similarly high proportion (86%) would choose the same school they are currently attending.

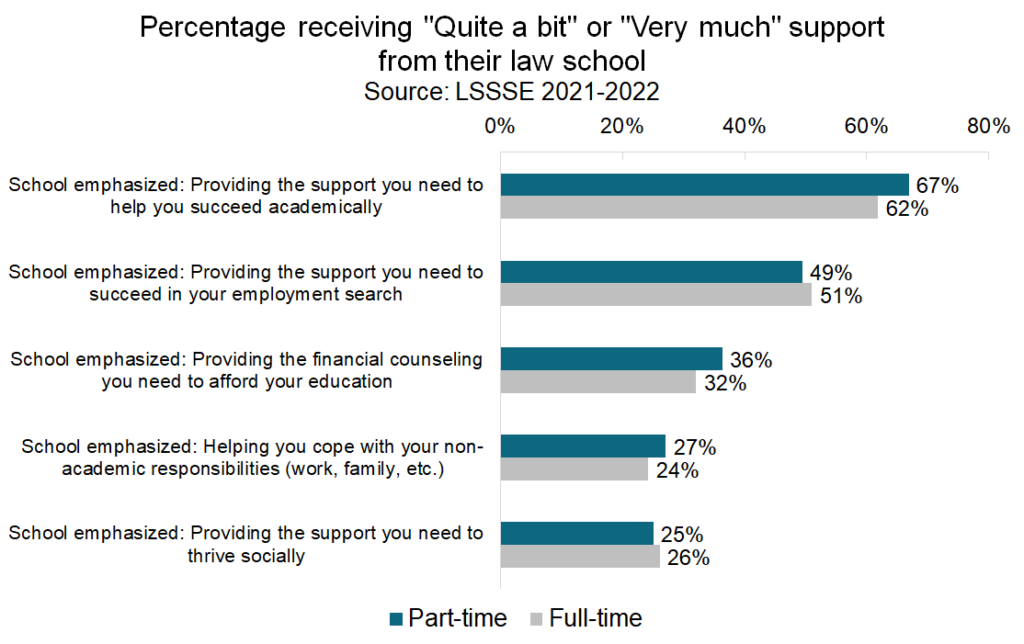

Part-time students feel a level of support from their law schools that is generally on par with – or higher than – the level of support experienced by their full-time colleagues. Two-thirds of part-time students feel that their school is providing the support they need to succeed academically. Around half feel that their law school is providing the support they will need to succeed to succeed in finding employment. Only a quarter of part-time students feel that their school provides the support they need to thrive socially, although this is nearly identical to the 26% of full-time students who feel similarly. Part-time students may require somewhat different considerations than their full-time peers, but they generally feel that their law schools provide adequate assistance to allow them to be successful.

Part-time students feel a strong connection to their law schools. They are fairly satisfied with the resources their law schools provide, and they are quite satisfied with their overall experiences as law students. Although their experiences as law students may be slightly untraditional, they are still highly engaged and active participants in their programs of legal study.

Part 1: Part-Time Students & the Law School Experience

Around 12% of law students attend part-time. This subpopulation of law students has a unique experience that differs from that of their full-time colleagues. In part one of this two-part series, we will explore the characteristics of part-time law students and describe some of the ways that they engage with the law school community and environment. In part two, we will look at how satisfied part-time students are with their law schools and the extent to which they feel supported in their success as students and as future legal professionals.

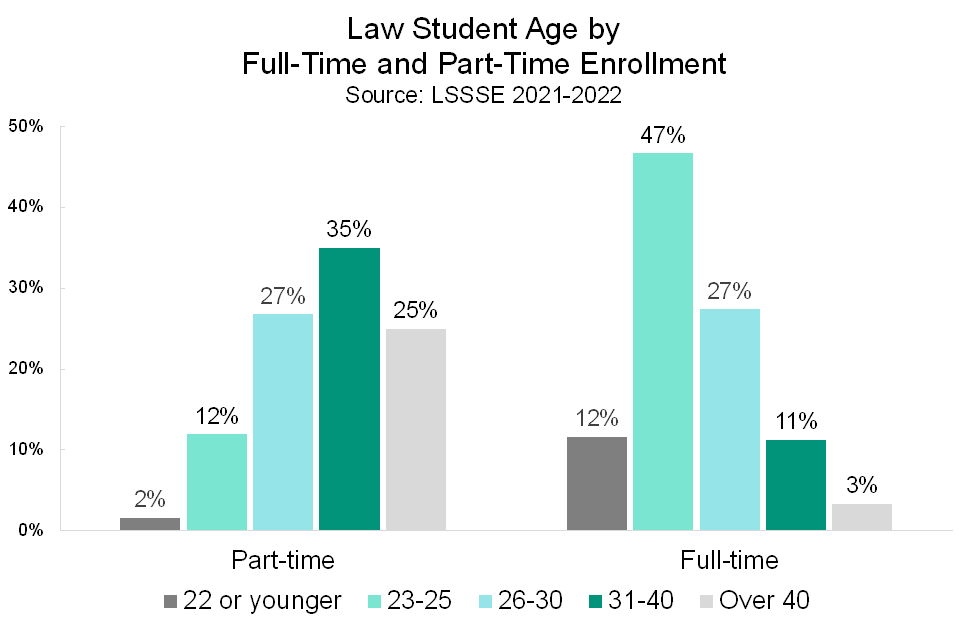

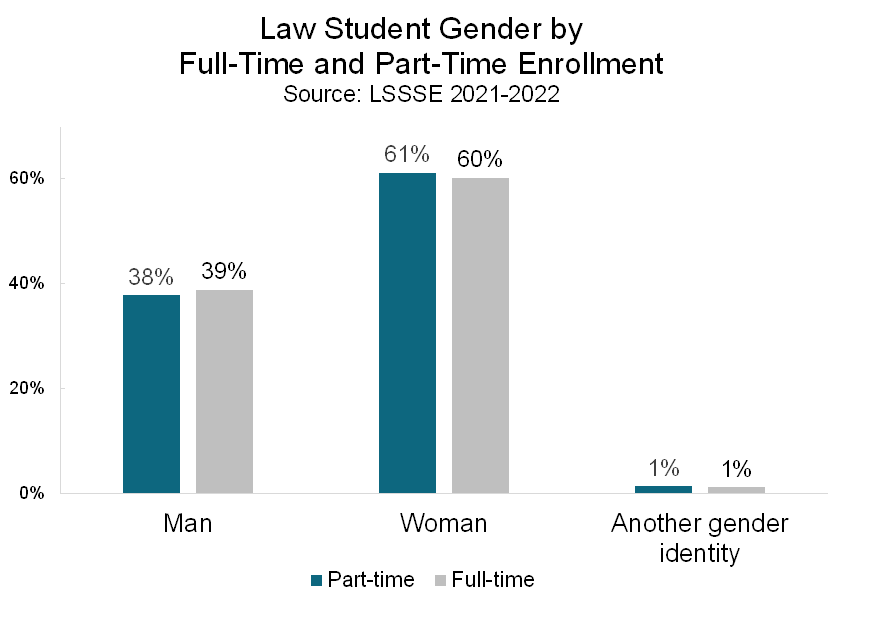

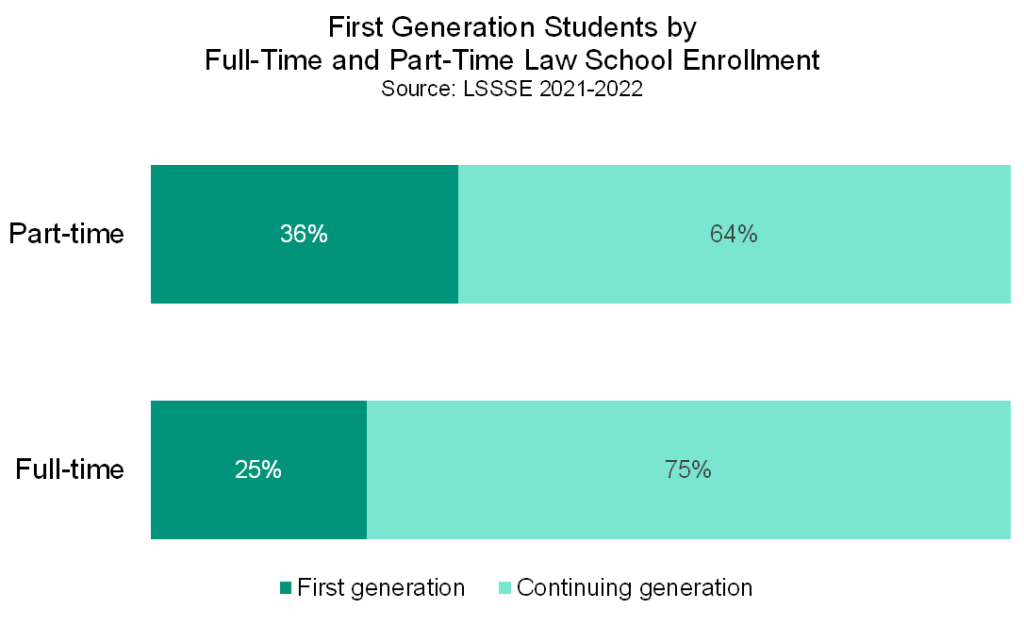

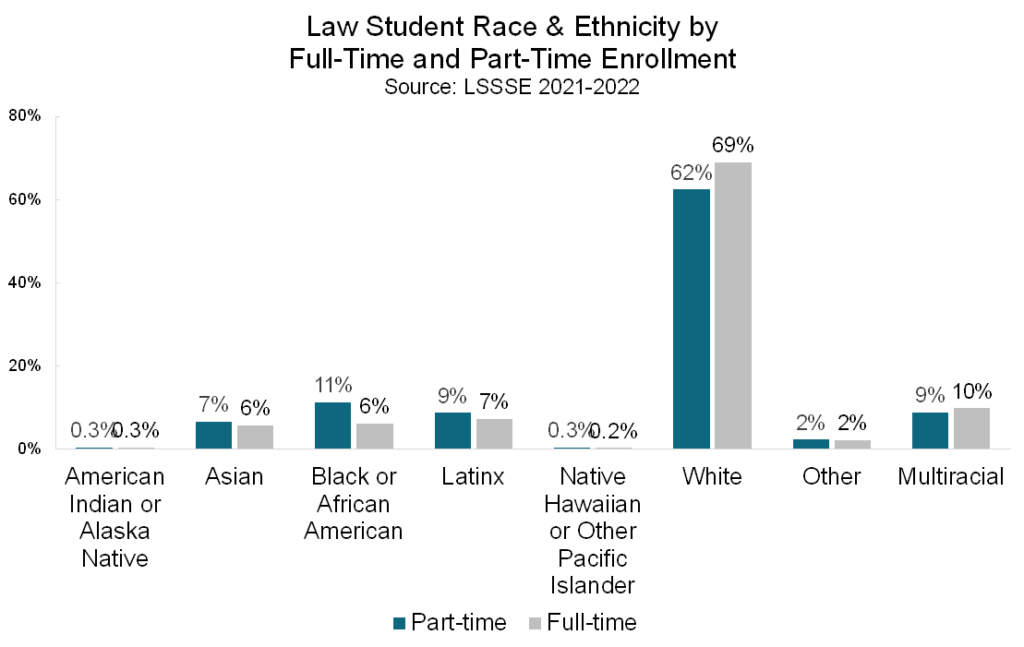

Part-time students tend to be somewhat older than their full-time classmates. Sixty percent of part-time students are over thirty years old compared to 14% of full-time students. In fact, one quarter (25%) of part-time students are over 40 compared to just 3% of full-time students. However, the proportions of men, women, and people of another gender identity are about equal between the two groups. Part-time students are more likely to be first generation (defined as a person whose parents did not graduate college) with over a third of part-timers (36%) falling into this category compared to only a quarter (25%) of full-timers. Part-time students are also more likely to be Black or Latinx.

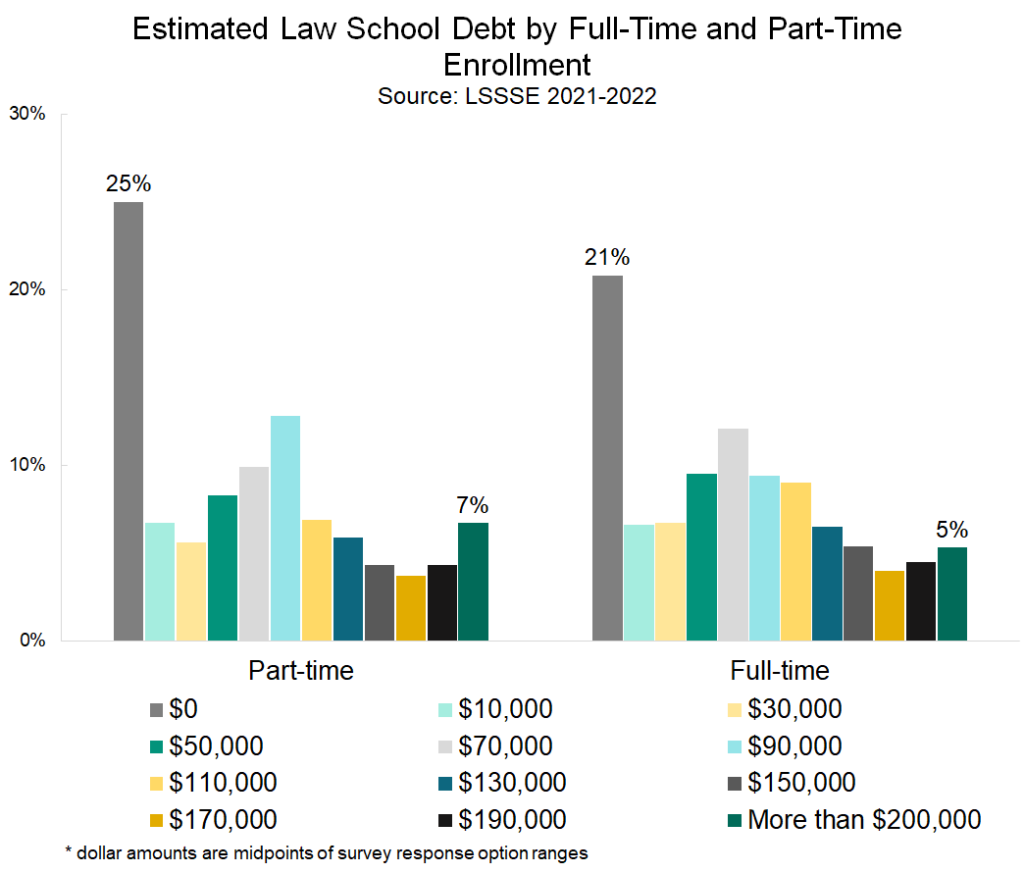

Part-time students are more likely than full-time students to expect to have no law school debt upon graduation, possibly because some part-time students are attending law school with the financial support of their employers. However, part-time students are also slightly more likely than full-time students to expect to owe more than $200,000, which is the highest debt category that LSSSE records. Seven percent of part-time students expect to owe this much compared to five percent of full-time students.

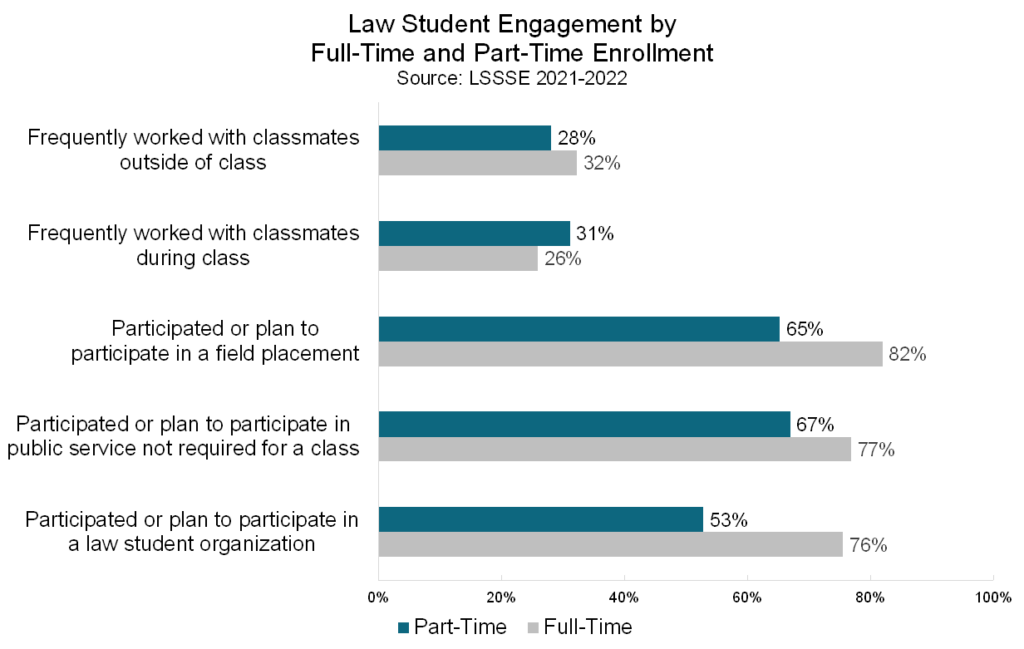

In terms of engagement with their coursework, more full-time students than part-time students frequently work with classmates outside of class to prepare class assignments. However, more part-time students frequently work with other students on projects during class time. Part-time students are somewhat less likely to engage in enriching experiences than their full-time counterparts, perhaps because they are more likely to have more intense work and family responsibilities. Still, about two-thirds (65%) of part-time students have completed or plan to participate in field placements and about two-thirds (67%) of part-time students have completed or plan to participate in public service. Additionally, over half (53%) of part-time students will join a law student organization before graduation. Part-time students are less likely than full-time students to partake in these opportunities, but their participation rates are still reasonably high given the other demands on their time.

Part-time students find ways to make the law school experience their own. This group of students tends to be older and slightly more ethnically diverse, and they are somewhat less likely to add enriching law school experiences to their schedules. In our next post, we will examine part-time students’ feeling toward their law schools and the support they receive from faculty and administrators.

Law Students Working Harder Than They Thought Possible

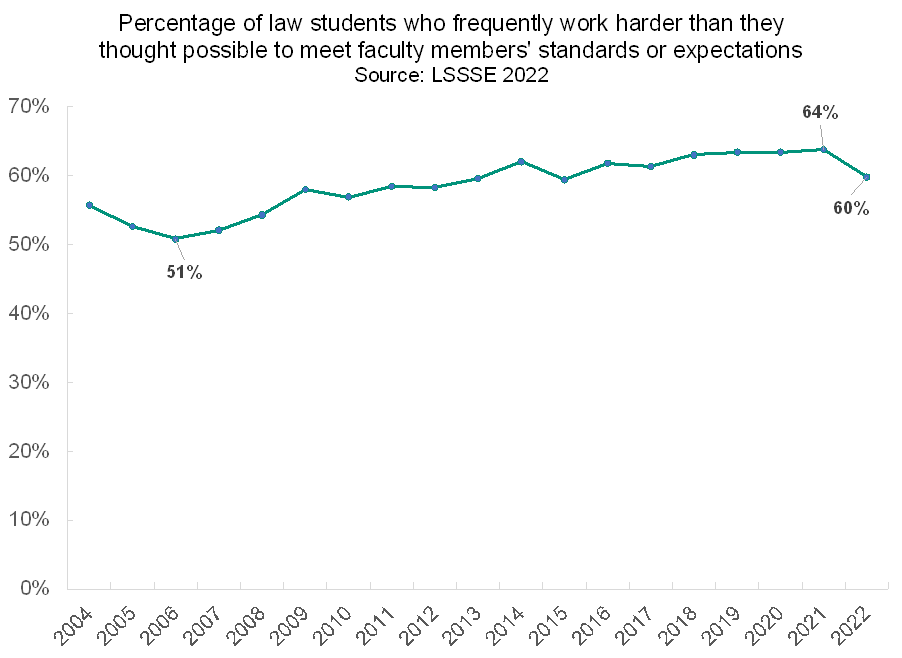

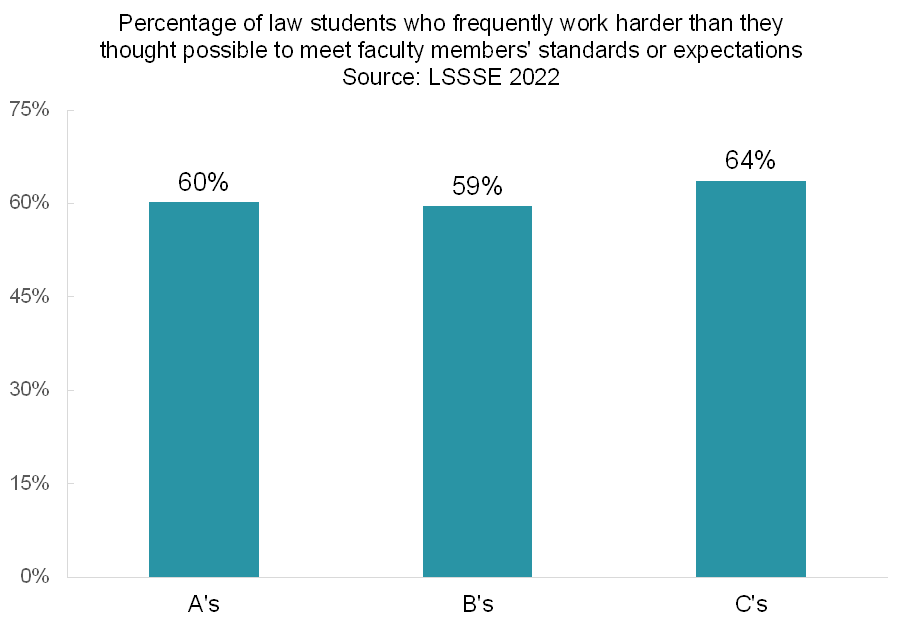

Faculty hold law students to high standards. In 2022, 60% of law students frequently worked harder than they thought possible to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations. This number has generally trended upward over the last twenty years, although the lowest recorded percentage of students frequently working harder than they thought possible was still a respectable slight majority (51%) in 2006. In 2022, only 8% of students never worked harder than they thought possible.

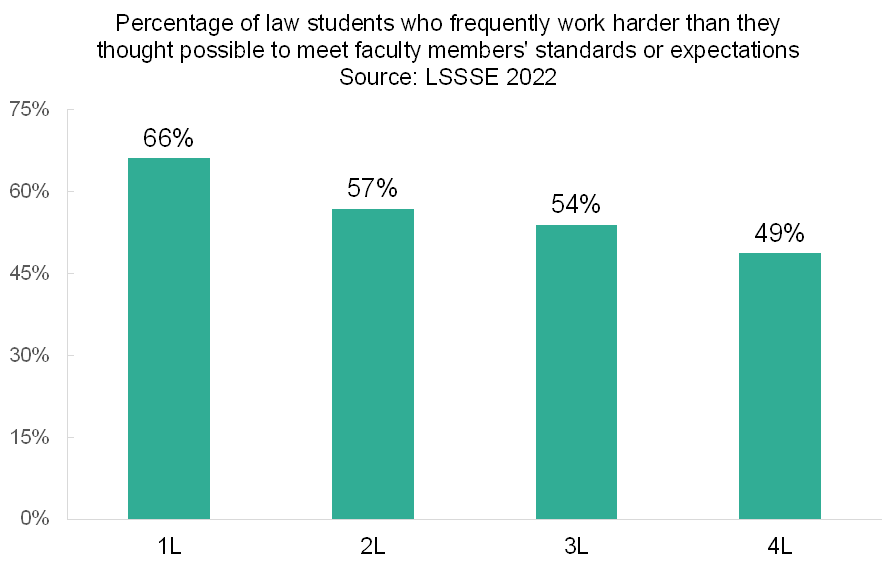

Somewhat unsurprisingly, students who are new to law school are more likely to push themselves to their limits than students who are accustomed to law school life. Two-thirds (66%) of 1L students frequently work harder than they thought possible compared to 54% of 3Ls and 49% of 4Ls. Perhaps new law students are particularly eager to prove themselves to their professors and peers or perhaps more senior students are accustomed to the way that the law school curriculum draws out their best performance and thus already know exactly how hard they can work.

Interestingly, students who generally achieve C grades in law school are more likely to frequently work harder than they thought possible compared to students who achieve mostly A’s and B’s. This may indicate that degree of effort is not always accurately reflected by scores on papers and exams for some students.

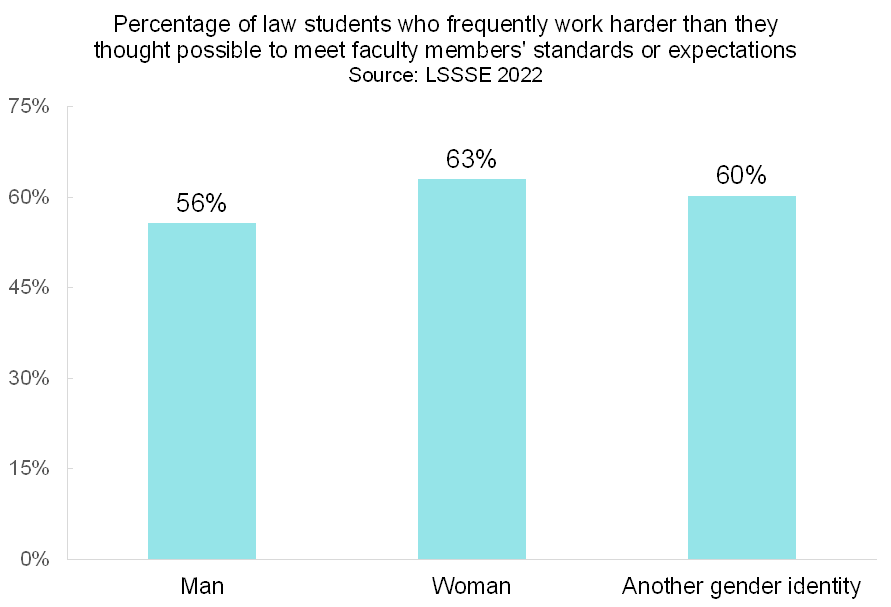

Finally, there are gender differences in the percentage of students who surprise themselves with the intensity of their efforts. Sixty-three percent of women frequently work harder than they thought possible to meet faculty standards or expectations compared to 56% of men. People with another gender identity fall in between at 60%. Ten percent of men and people with another gender identity never work harder than they thought possible compared to only 7% of women.

The data are clear that attending law school is a challenging and demanding endeavor. Most students rise to the occasion by pushing themselves to do their best work in order to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations. Hopefully these efforts are counterbalanced by supportive law schools who also foster good self-care and community care practices for budding legal professionals.

Success with Online Education: Classroom Environment

Our last post shared some general findings about online learning from our 2022 Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf). In this post, we will share evidence that online classrooms appear to encourage a more diverse cross-section of students to participate in class discussions. We will also share reassuring signs that online law students are learning as much as their in-person counterparts.

Online discussions feature diverse voices

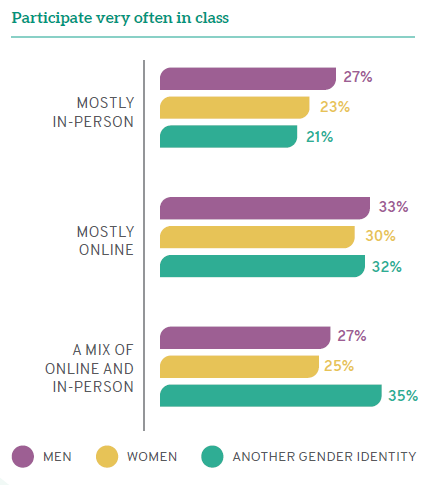

Online classes excel at inviting participation from a broader range of students than in-person classes. Men are equally likely to participate in class discussion and ask questions “often” or “very often” whether participating in person (60%) or online (61%). However, women taking mostly online courses are more likely to engage in class “often” or “very often” (58%) compared to women taking mostly in-person courses (53%). In fact, online courses appear to encourage all students to engage more intensely with class discussion. One quarter of students (25%) who take primarily in-person classes participate “very often” compared to 31% of students taking mostly online classes. There is a marked gender difference, with 23% of women participating “very often” in person but a full 30% participating “very often” online, and only 21% of those with another gender identity participating “very often” in person while 32% do so online. The online environment–perhaps because of the mechanisms for turn-taking or because it is more comfortable for students to volunteer– invites more voices to engage in the conversation.

Online students are learning as much as in-person students

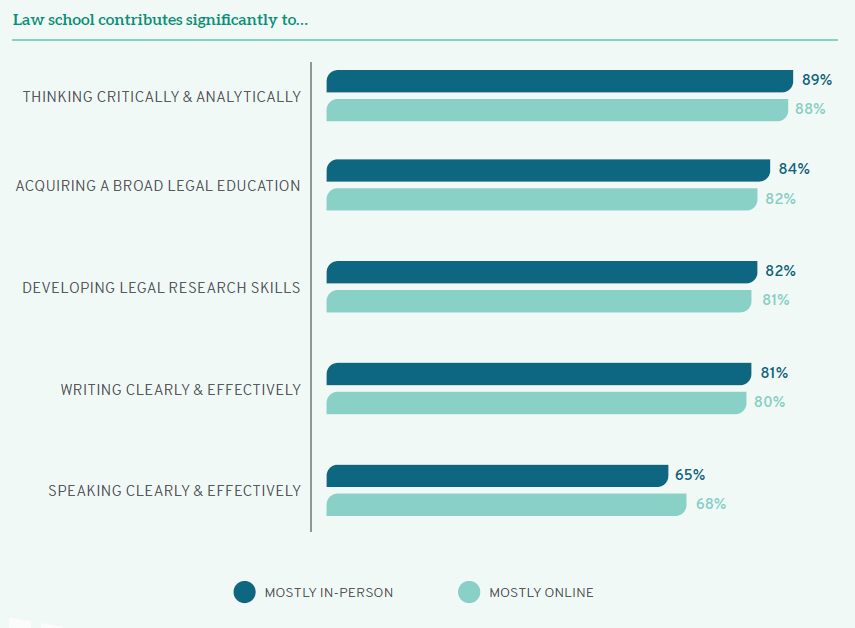

Regardless of how they attend classes, most students are confident that they are developing crucial legal skills. Nearly 90% of online and in-person students are learning to think critically and analytically. More than four out of five online and in-person students say they are acquiring a broad legal education (82% and 84%, respectively) and developing legal research skills (81% and 82%, respectively). Interestingly, online students are more likely to be developing the ability to speak clearly and effectively, perhaps because online courses invite more participation from a diverse range of students. Thus, law school classes do not lose their intellectual rigor when they are offered in an online format.

Online law school classes can be highly successful and well-received by students. Many students who take most of their classes online are as satisfied—and sometimes more satisfied—than their peers who attend classes primarily in person. Furthermore, law students who attend classes via either modality are equally likely to feel confident that they are learning important skills that will help them succeed as legal professionals. Although the law school experience is unlikely to be primarily online again, the accelerated transition to offering online courses that occurred due to COVID-19 shows that the online law school experience can be as successful, enriching, and satisfying as the traditional law school curriculum.

Success with Online Education: Relationships

The latest LSSSE Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf), focuses on the largely positive online learning experiment that law schools embarked upon due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This week and next week we will share selected snippets from the results. In this post we will describe how the switch to online learning impacted relationships among law students, law faculty, and administrators.

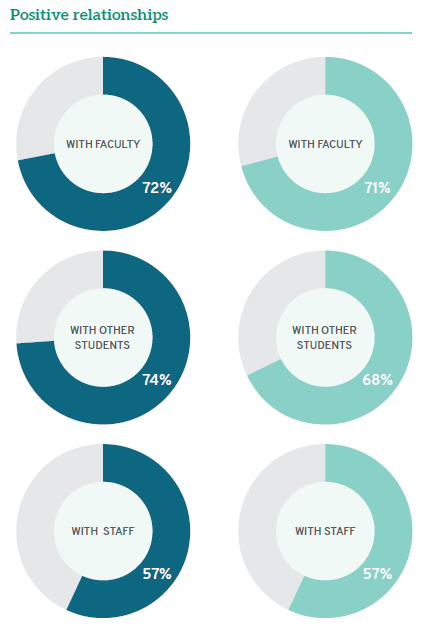

LSSSE data confirm other research showing how law school faculty have invested an enormous amount of energy and effort to connect with students, regardless of instructional modality. A full 72% of students taking mostly in-person classes have strong relationships with faculty (5 or higher on a 7-point scale), and 71% of mostly online students feel the same way. Students remain highly engaged with faculty in an online environment.

Online students and in-person students are equally likely to have positive relationships with administrative staff. A little over half (57%) of each group rate their relationships with their law school’s administrators a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale. Career services-oriented staff could consider using these relationships to bring more targeted career guidance to online students to narrow the gap in career preparedness between online students and in-person students. However, the relatively low percentage of both in-person and online students who have strong relationships with staff is a point of concern that should be addressed to better support law student development.

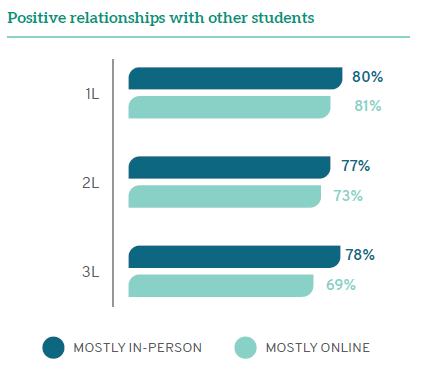

Despite similarly positive relationships with professors, students in mostly online classes are less likely than others to have strong relationships with each other. Only 68% of online students rate their relationships with their classmates positively, compared to nearly three-quarters (74%) of in-person students. There is again a disparity across class years, with 1Ls having similarly positive peer relationships regardless of mode of attendance and online 3Ls being much less likely to enjoy strong relationships with their peers than 3Ls attending in person. There may be a loss of social connections among online students because of a lack of the sort of incidental contact that builds relationships over time.

Next week we will discuss the learning experience in the virtual classroom. For the complete story, you can view the entire report on our website.

Engagement with Law Student Organizations

Law student organizations are important venues for developing law students’ professional identities. Through networking, invited speakers, and events, these organizations foster a sense of community and provide students the opportunity to more intensely explore areas of law that interest them. [1]

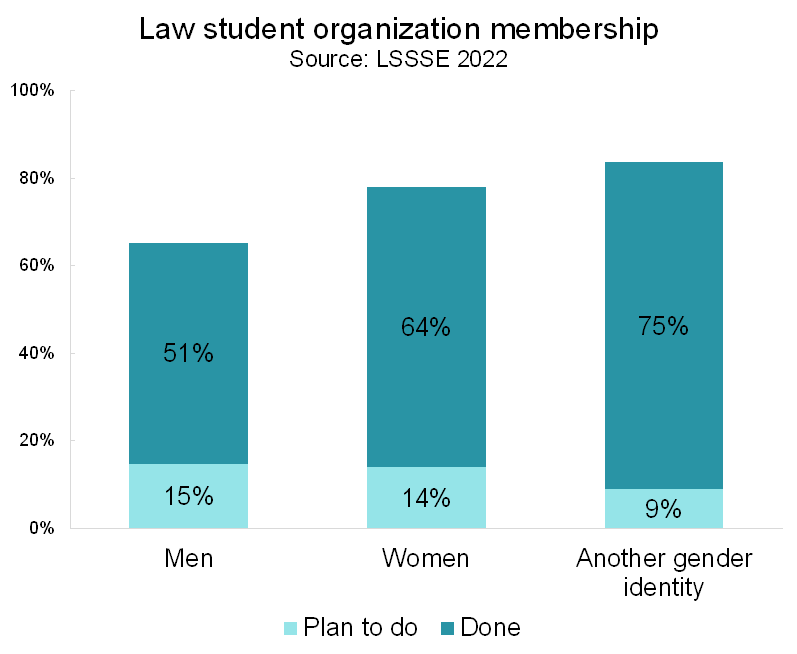

Law student organizations are among the most popular enriching activities at law schools. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of law students either plan to join a law student organization or have already done so. About 31% of students have served as law student organization leaders, and another 18% plan to take on a leadership role before they graduate. Men are less likely to join student organizations compared to women and those of another gender identity. In 2022, just 51% of men had already joined an organization compared to 64% of women and 75% of those with another gender identity.

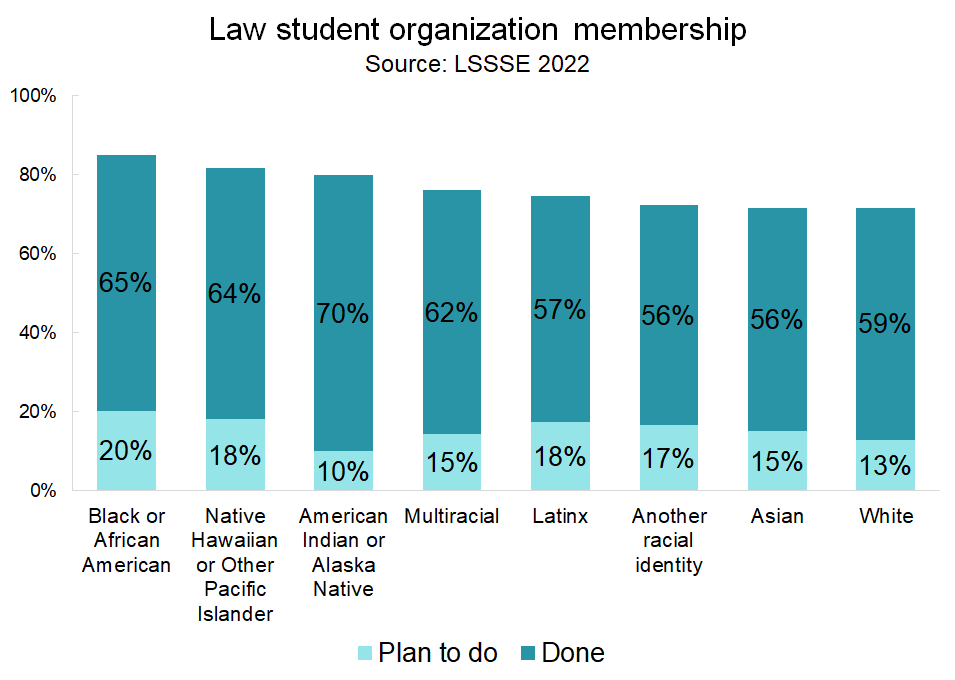

Black students are particularly engaged as members of law student organizations, with 65% of Black students participating and another 20% planning to do so. Native Hawaiian students, American Indian students, and Alaska Native students have similarly high levels of engagement with law student organizations, while Asian and white students have the lowest participation rates.

Women, gender-diverse people, and students of color are most likely to join student organizations. Thus, these organizations likely play a vital role in connecting law students who traditionally face higher barriers in accessing higher education and assimilating successfully into the legal profession. Law student organizations also given students the opportunity develop their leadership skills and to work with their professors and classmates in a non-classroom context.

____

[1] See Andrew Hitt, The importance of student organizations, (Aug. 27, 2009), https://law.marquette.edu/facultyblog/2009/08/the-importance-of-student-organizations/

Relationships with Law Faculty

Law students generally have strong relationships with law school faculty members. In 2022, 71% of LSSSE respondents ranked their relationships with faculty a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale, where 7 represents faculty who are “available, helpful, and sympathetic.” Only 12% of students ranked their relationships a 3 or lower, and a mere 1% of students ranked their relationships a 1, meaning they feel that the faculty at their law school are “unavailable, unhelpful, and unsympathetic.”

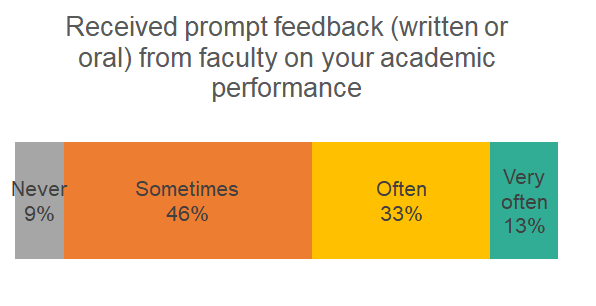

Relationships with instructors are built both inside and outside the classroom. More than half (53%) of law students discussed assignments with a faculty member often or very often, and only 5% never discussed assignments with a faculty member. After completing assignments, most law students (91%) receive prompt feedback from faculty on their academic performance at least sometimes. However, only 13% say they receive prompt feedback very often, and 9% never receive prompt feedback.

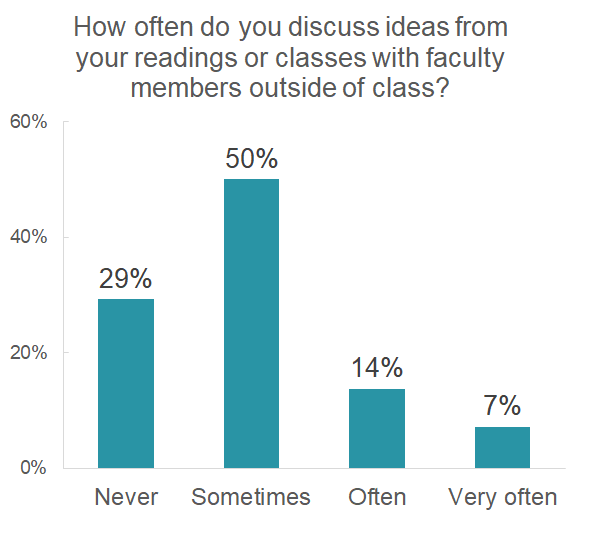

About one in five students (21%) often or very often discussed ideas from their readings or classes with faculty members outside of class, and another half (50%) did so sometimes. This practice tapers off a bit over time, with 22% of first-year students discussing ideas with faculty members outside of class often or very often compared to 19% of 3Ls and 11% of 4Ls.

Law school faculty can provide crucial guidance about navigating the legal job market, and the vast majority of students (84%) take advantage of their advice. Just over a third of students (36%) discuss their career plans or job search activities with a faculty member of advisor often or very often. Around 82% of first-generation students (neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree) have discussed their career plans with faculty compared to 85% of their non-first-generation peers.

The relationships students form during their time in law school can be crucial to their future success. The majority of law students make the most of these relationships, and they appreciate the support and knowledge they receive from the faculty of their law schools.

New Questions Focusing on Law Students with Disabilities

By popular demand, LSSSE is now capturing information about the experience of law students with disabilities. Law students are given the opportunity to select one or more conditions using the following questions:

Have you been diagnosed with any disability or impairment?

- Yes

- No

- I prefer not to respond

Which of the following impacts your learning, working, or living activities?

- Sensory disability

- Blind or low vision

- Deaf or hard of hearing

- Physical disability

- Mobility condition that affects walking

- Mobility condition that does not affect walking

- Speech or communication disorder

- Traumatic or acquired brain injury

- Mental health or developmental disability

- Anxiety

- Attention deficit or hyperactivity disorder (ADD or ADHD)

- Autism spectrum

- Depression

- Another mental health or developmental disability (schizophrenia, eating disorder, etc.)

- Another disability or condition

- Chronic medical condition (asthma, diabetes, Crohn’s disease, etc.)

- Learning disability

- Intellectual disability

- Disability or condition not listed

- Please describe your disability or condition

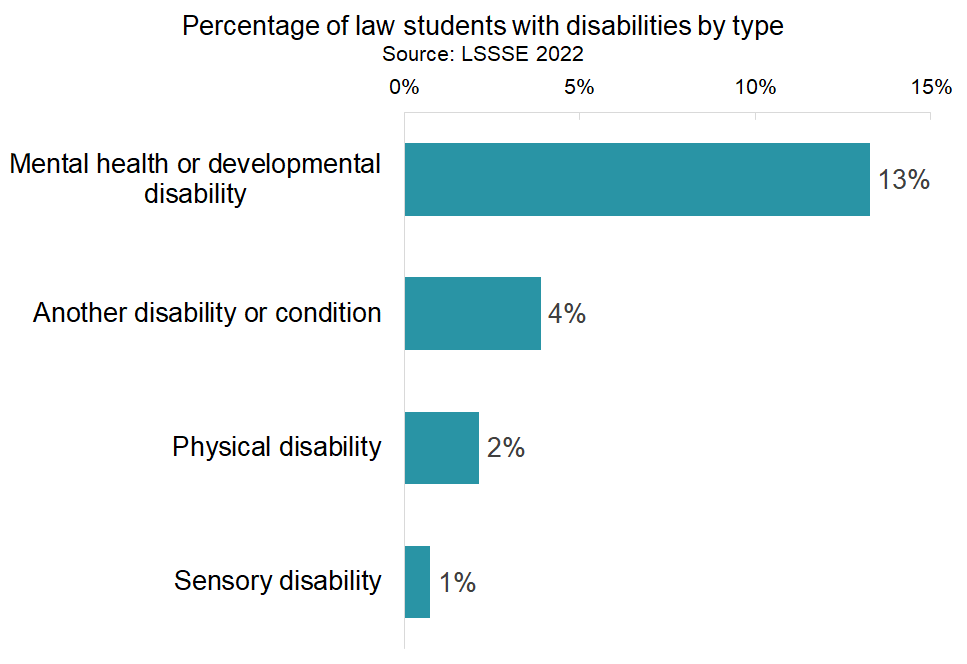

In 2022, nearly one in five (19%) of LSSSE respondents had a disability. Students who responded "yes" to the disability question then had the option to select the condition(s) that impact their learning, working or living activities. Mental health conditions were by far the most common, with about 13% of law students having a condition such as anxiety, ADHD, or autism. Four percent of law students had a condition not specified on the survey such as a chronic health condition or a learning disability. Two percent of respondents had a physical disability, and one percent had a sensory disability such as being deaf or hard of hearing.

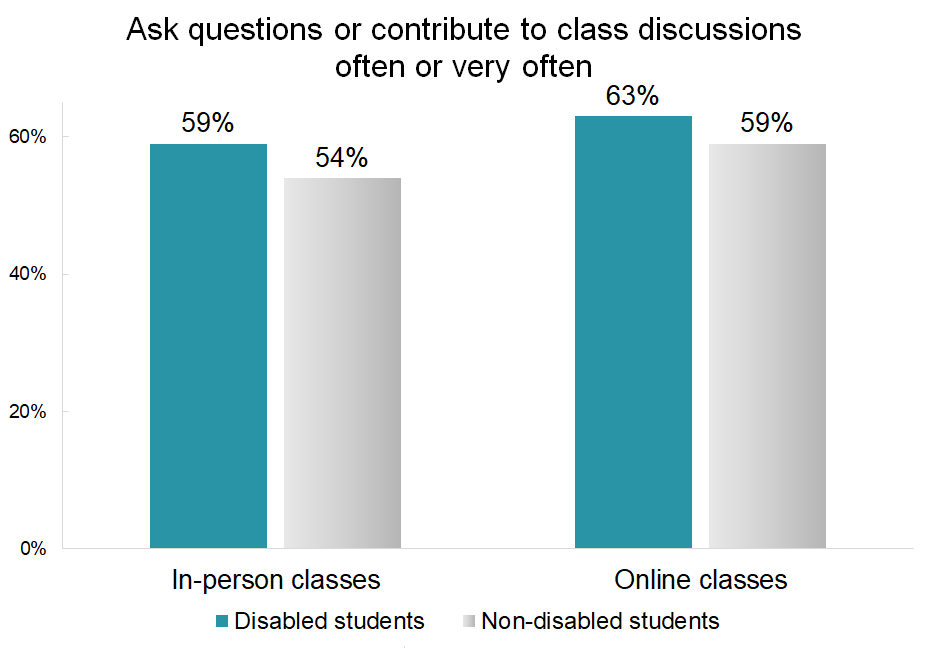

In addition to tracking the overall proportion of law students who are disabled, these new data give us an exciting opportunity to explore how students with disabilities might engage differently with their law schools and what particular experiences or services law schools can offer to better help these students succeed as professionals. For example, law students who have a disability are more likely to participate in class discussions, both online and in person, compared to their non-disabled peers. Additionally, students with disabilities are more likely to engage in pro bono work or public service during law school. Near four out of five students with disabilities (79%) either plan to or have done pro bono work or public service compared to 74% of non-disabled students.

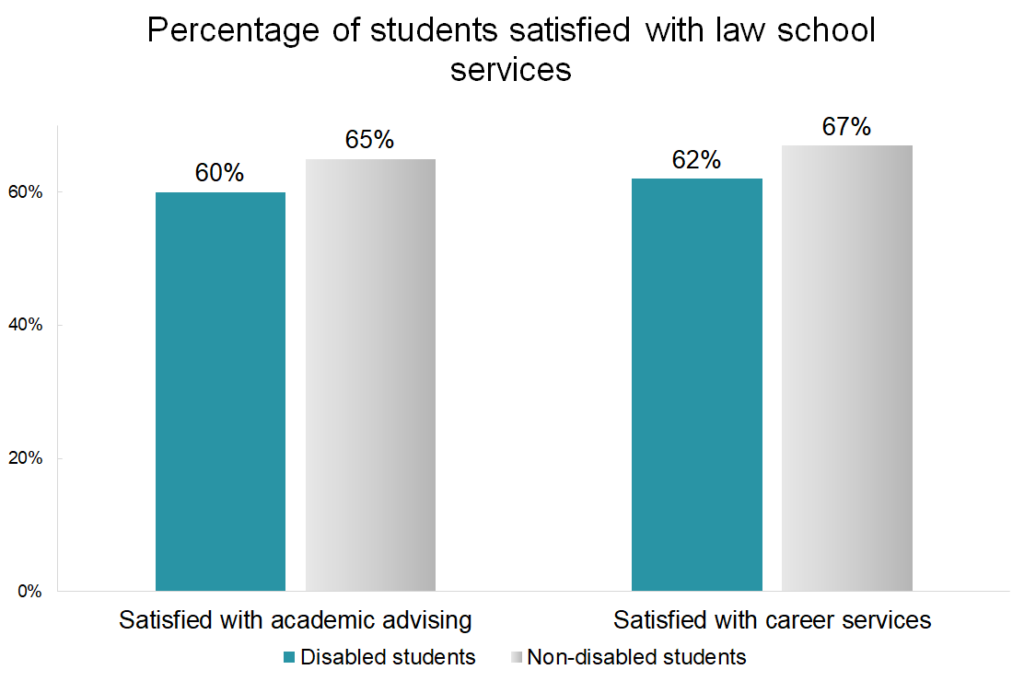

However, disabled students are less likely to be satisfied with their experiences with academic advising and career advising compared to their classmates. This suggests that law students with disabilities engage intensely with the law school experience but do not always feel as supported as their non-disabled peers.

The new disability questions are included in the core LSSSE survey and available to all participating law schools. Survey registration will be opening soon; contact LSSSE for more details!