What Do 1L Students Plan to Do in Law School?

Most students complete law school in three years. With intense coursework and notoriously challenging reading loads, law students must be selective about how they allocate their time toward extracurricular activities. Which enriching activities had 1L students completed or planned to complete before graduation in 2019 and 2020? Check out our interactive visualization below to see.

** Note that non-binary students are included only when the population was large enough to ensure student anonymity in aggregate reporting.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Diversity Skills

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our final post in this series, we will explore how law schools can teach skills to equip students to interact with people from different backgrounds.

Schools have a responsibility to not only admit and provide the resources to enroll a diverse class of students, but to impart the skills these students will need to be effective lawyers. Increasingly, the practice of law requires sensitivity to issues of race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Law schools can empower students first by encouraging them to reflect on their own identities, and then supplying coursework on issues of privilege, diversity, and equity; while it is important for students to learn about anti-discrimination and anti-harassment, law schools should also equip them with the tools they will need to fight these social problems as attorneys and civic leaders.

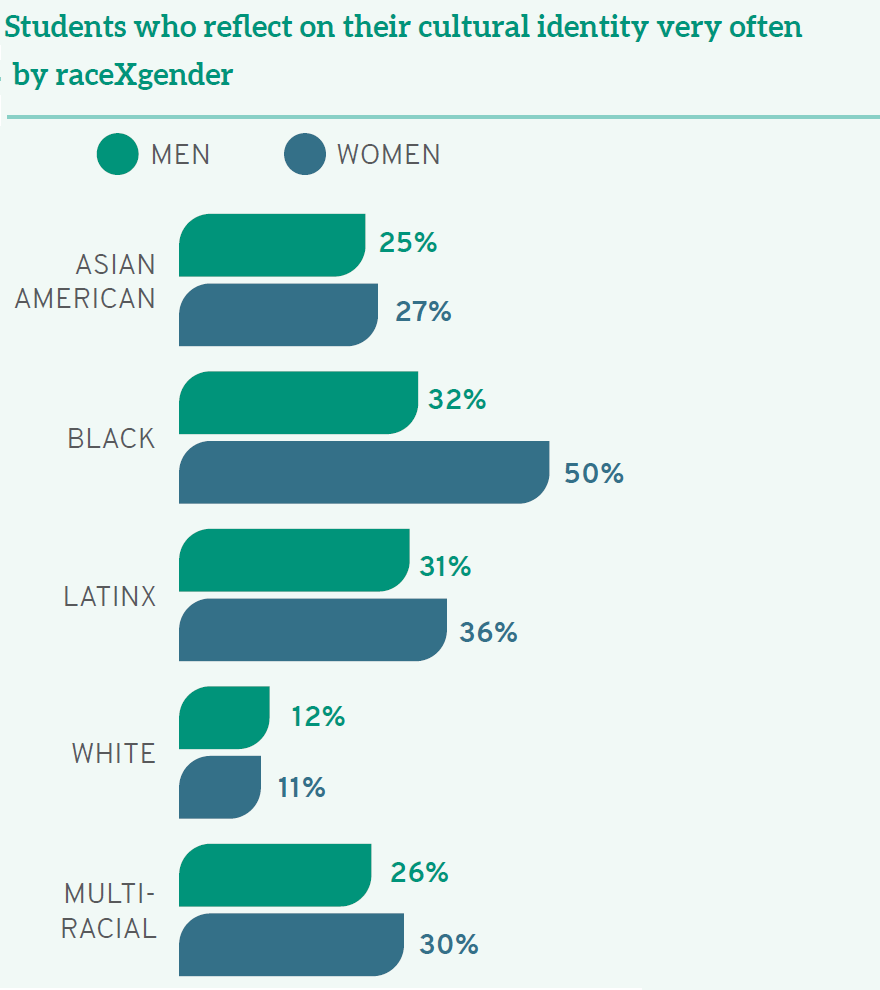

Yet schools are, by and large, not preparing law students to meet these challenges and succeed as leaders. When students were asked how frequently they reflect on their own cultural identity, only 12% of White students do so "very often," compared to 50% of Native American students, 44% of Black students, and 34% of Latinx students. Even more alarming, over a quarter (26%) of White students never reflect on their cultural identity during law school. When we consider the intersection of raceXgender, an even more troubling picture emerges. A full 28% of White men and 25% of White women in law school never reflect on their cultural identity, compared to the 50% of Black women who do so "very often."

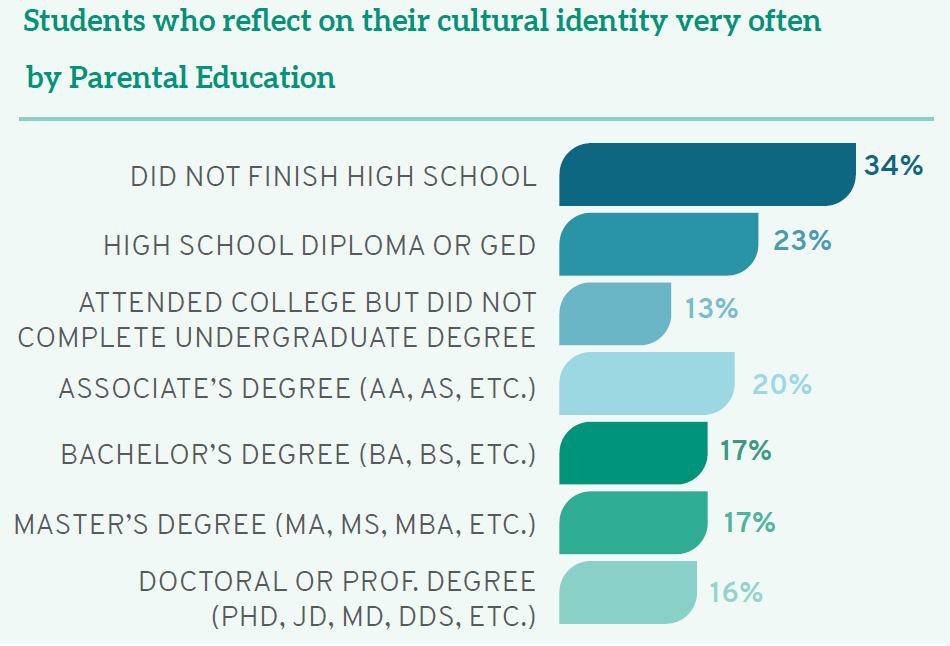

Students whose parents have less formal education are also more likely to reflect on their cultural identity, including 34% of those whose parents did not finish high school as compared to 16% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree. In sum, students with racial, gender, or class privilege are less likely to reflect on the benefits associated with their identity.

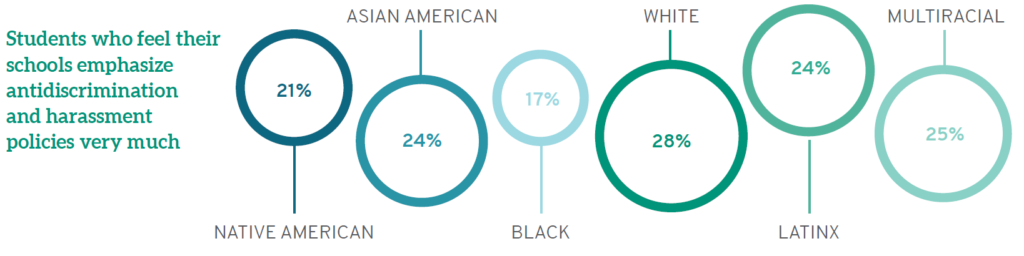

Even without self-reflection, students can nevertheless gather information about anti-discrimination and harassment policies. LSSSE data show that while White students see their schools as prioritizing this information, students of color do not agree at the same high levels. Similarly, men (31%) are more likely than women (23%) and those with another gender identity (11%) to believe their schools strongly emphasize information about anti-discrimination and harassment. Considering raceXgender, a full 27% of Black women see their schools as doing "very little" to share information on anti-discrimination and harassment, while 32% of White men believe their schools do "very much" in this regard.

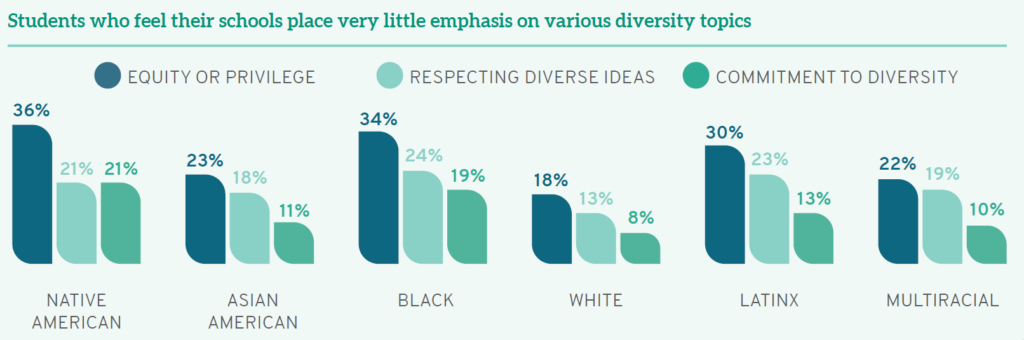

Equally troubling, students from different backgrounds perceive institutional emphasis of various diversity-related topics in starkly divergent ways. Although White students believe that their schools emphasize issues of equity or privilege, respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and a broad commitment to diversity, students of color are less likely to agree. Students of color—including those who are Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, and multiracial—frequently note and appreciate assignments or discussions of race/ ethnicity and other identity-related topics in the classroom; yet they are more likely than their White peers to report that schools place “very little” emphasis on diversity issues. Women are similarly more likely than men to believe their schools do “very little” to emphasize diversity in coursework. Furthermore, higher percentages of Black women report “very little” emphasis on equity or privilege (36%), respecting diverse perspectives (27%), and an institutional commitment to diversity (21%)— compared to high percentages of White men who believe their schools are doing “very much” in all three arenas (20%, 24%, and 34%, respectively). First-gen students are also more likely than their classmates whose parents completed college to note “very little” diversity coursework. Synthesizing these data, students who are traditionally underrepresented and marginalized—arguably the students who have the most personal experience with issues of diversity—see their schools as doing less to promote diversity and inclusion than those who are privileged in terms of their race/ethnicity, gender, and parental education.

As part of a broad curriculum that sets up students for their future practice, law schools should teach students diversity skills—a set of skills that facilitate success in our increasingly globalized society, ranging from personal reflection to the tangible tools lawyers can use to combat discrimination. Law schools that succeed at these diversity-related endeavors will be preparing our nation’s newest lawyers to meet the full range of challenges ahead.

Guest Post: Connections and Community in Distanced Classrooms

Guest Post: Connections and Community in Distanced Classrooms

Jessica Erickson

Jessica Erickson

Professor & Associate Dean for Faculty Development

University of Richmond School of Law

Law faculty put significant thought into designing courses. We draft learning objectives, carefully craft assessments, and consider how to engage students inside and outside of the classroom. When law school courses suddenly moved online, many faculty had to think about a new aspect of course design how to build connections in classrooms where students were remote. Even in classes that were able to meet in-person, many of us found it difficult to develop a classroom community when students were in masks and seated six feet apart.

When we could no longer have casual conversations with students after class or in the hallways, many of us realized just how crucial these connections are for our students and for us. In this blog post, I discuss the importance of relationships to student learning and outcomes, as well as how to develop these relationships in online, hybrid, or physically distanced classes.

- The Importance of Relationships

Connections and community are essential to student learning. As I have previously discussed, research from undergraduate institutions shows that a sense of community is associated with increased motivation, greater enjoyment of classes, and more effective learning. Crucially, data from the Law Student Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) shows that these connections matter to law students as well. LSSSE data has been used to examine both the inputs and outputs of law students’ sense of belonging. Using LSSSE data, we can gain insight into what causes law students to feel a sense of belonging (inputs) and the impact that a sense of belonging has on law students’ performance in law school and their career (outputs).

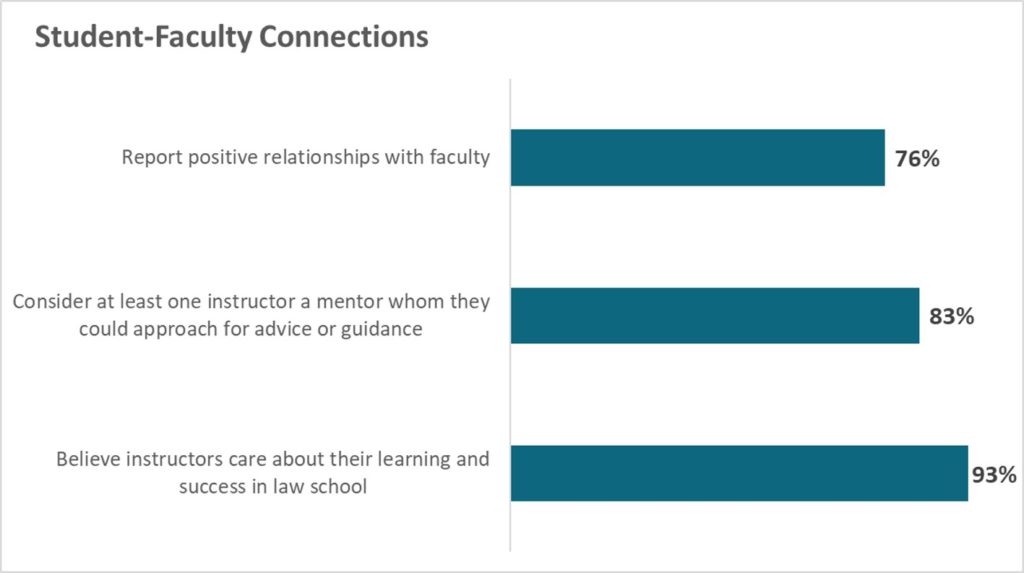

Starting with inputs, LSSSE’s 2018 report Relationships Matter surveyed more than 18,000 students at 72 law schools. The report concludes: “Relationships with faculty, administrators, and peers are among the most influential aspects of the law student experience. These connections deepen students’ sense of belonging and enhance their understanding of class work and the profession.” Connections, in other words, are key when it comes to fostering law students’ sense of belonging. Law schools are doing a good job at developing connections, with 83% of students stating that they have at least one faculty member whom they could approach for advice or guidance.

When it comes to outputs, we can look at research by Professor Victor D. Quintanilla using LSSSE data. He found that a sense of belonging significantly predicted three key outputs – (1) students’ overall experience in law school, (2) whether they would choose to go to law school again, and (3) their academic success (i.e., law school GPA). Moreover, not only does a student’s sense of belonging predict academic performance, but the impact was even greater than other commonly used predictors such as undergraduate GPA and LSAT scores. This means that, even if students come to law school with different academic backgrounds, we can help close this gap by fostering our students’ sense of belonging.

Unfortunately, the research also suggests that building this sense of community is much harder in online or hybrid courses, which most of us who taught this past fall can probably confirm. Now we need to think even more deliberately about how to develop these connections in our classes.

- Building Relationships in Remote or Physically Distanced Classrooms

This past summer, I wrote two blog posts, one with suggestions on how faculty can connect with students in these new learning environments and the other with suggestions on how faculty can help students connect with each other. In this post, I want to reflect back on these strategies now that I have tried many of them with my own students.

First, I found office hours to be a key way to connect with students. I renamed my office hours “student hours” on the advice of a colleague, and I borrowed language from this same colleague to include in my syllabus: “I call these ‘student hours’ for a reason: they are for you. You should come to these student hours if you have a question about the course, but you can also just stop by to introduce yourself, ask any other questions, or talk about your law school experience. I want to get to know you!” At the start of each meeting, I talked with students about how law school was going, and it was a great opportunity to get to know them better.

I call these ‘student hours’ for a reason: they are for you. You should come to these student hours if you have a question about the course, but you can also just stop by to introduce yourself, ask any other questions, or talk about your law school experience. I want to get to know you!

Second, I used technology to connect with students individually. I asked each of my students to create their own Google Doc and share it with me, and they were required to compete short pre-class assignments in their Google Docs. I’ve used this strategy in the past, and found it to be a great way to make sure that students understand the reading. This semester, though, I set aside 1-2 hours before each class to include personal comments on each students’ assignments. I had 52 students across two classes, so it took a while, but it allowed us to connect more personally. I also gave them “Just for Fun” optional questions to include in their Google Doc where they could tell me their favorite board game or share a picture of their pet. I featured a few at the start of class, which was a fun way to personalize a class full of masked students. You can read more about my pre-class assignments here.

Third, several of my colleagues set up individual and small-group meetings with students. One colleague held individual “office hours” with each student. Another who taught a hybrid class met separately with all of her students who were fully remote. A third held online coffee breaks with 3-4 students at a time where the only rule was that they could not talk about course material.

Fourth, optional events allowed me to connect with students in a more relaxed way. In class, I was often preoccupied with the day’s material and all of the tech challenges of my hybrid classroom. In optional events, however, we could talk and connect in a lower-stakes way. I held an optional discussion about a Supreme Court oral argument. I also held review sessions and a Civil Procedure game night where students competed in an online kahoot! If you’ve never tried a kahoot!, I strongly recommend it. It was a great way to let students test their knowledge and have fun at the same time.

Finally, I created opportunities for students to connect with each other. Many faculty were not sure whether students could work in groups six feet apart and wearing masks. It turns out that students can work together pretty easily even under these circumstances. Although it was tempting to incorporate more individualized assessments to keep students separated, it’s important to give them opportunities to deepen their learning with each other. I sometimes felt like a middle school dance chaperone reminding students to stay an appropriate distance apart, but it was worth it.

The final thing I will add is that we need to be careful that our efforts to connect with students do not overwhelm them or us. It is tempting for these community-building exercises to be added on top of what we already ask our students to do in our courses. Now that we have some experience in these new classroom settings, we can be a bit more selective in what we choose to include and assess whether we need to scale back in other areas. At the end of the day, though, as LSSSE data has shown us, relationships matter, and we need to think about how to cultivate these relationships even in these unusual times.