Guest Post: How Sending One E-mail a Week Helped Me Connect Better to My Law Students

Guest Post: How Sending One E-mail a Week Helped Me Connect Better to My Law Students

Jonah E. Perlin

Associate Professor of Law, Legal Practice

Georgetown Law School

Building connections with our students is one of the most valuable things we can do as law professors. Not only do these connections help us become stronger teachers, connection is also integral to our students’ success. As LSSSE’s “2018 Relationships Matter Survey” explained, “Law students who build strong connect ions with faculty, administrators, and classmates are more likely to appreciate their legal education overall and also have better academic and professional outcomes.”

But during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when many law school courses including my own moved from the physical classroom to the digital world it became more challenging to create these connections. Gone were the informal chats in the hallway before and after class. Gone were the opportunities for a student to just “stop by” my office. Gone were the chance meetings in the cafeteria. Gone were so many of those regular but informal moments that help transform professor-student relationships from transactional to personal.

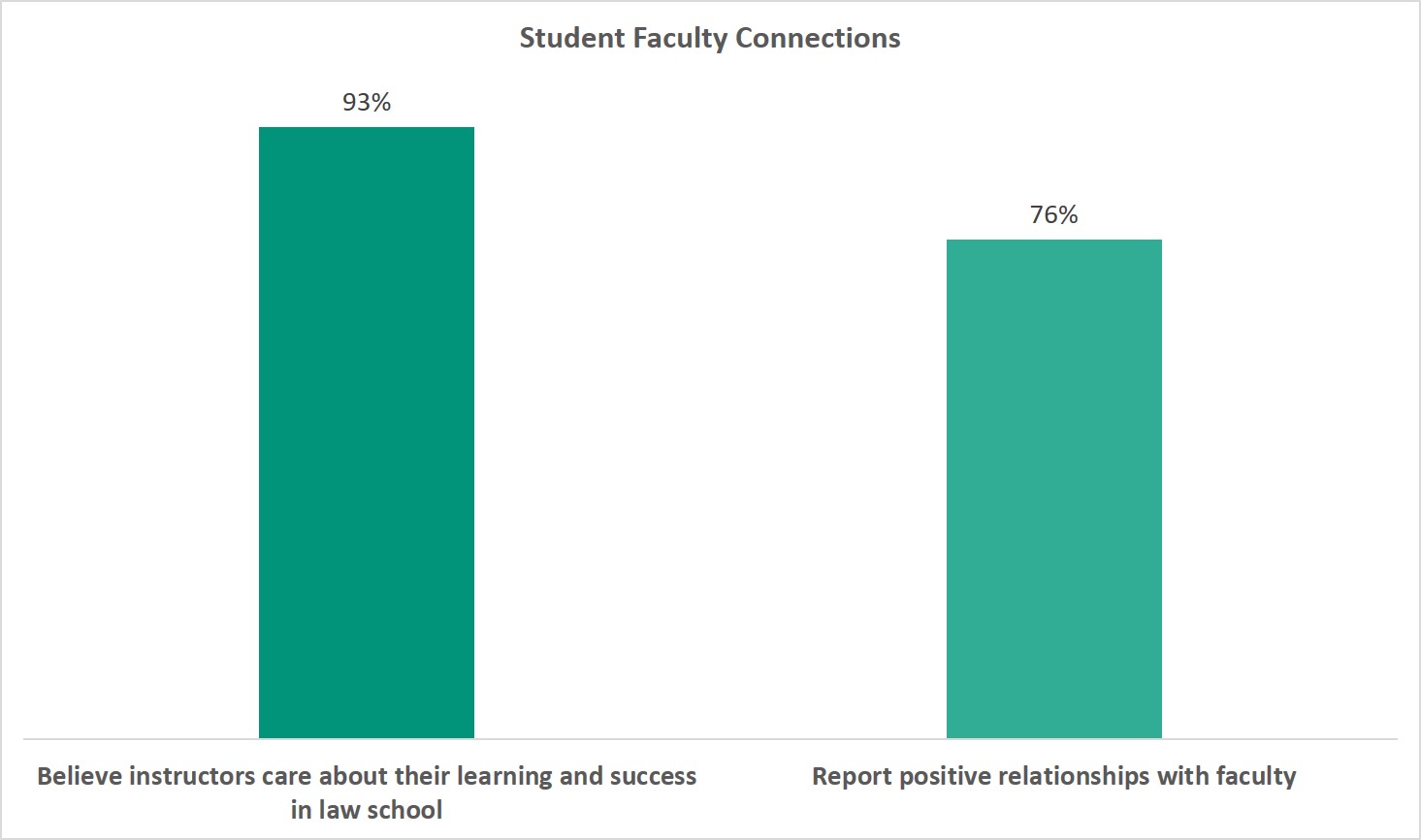

As the “Relationship Matters Survey” also reports a staggering 93% of law students believe that their instructors care about their learning and success in law school but the new reality required new pedagogical techniques to maintain this level of connection.

During the three semesters that I taught remotely, I tried several techniques to build this deeper personal connections with individual students and with my class as a whole. Some worked. Some didn’t. But what surprised me was that the single most successful tool to build connections with students in my first year course--and one which I continue to use even now that I have returned to teaching in-person--is sending a weekly takeaway e-mail.

Yes, you read that right. Writing one takeaway e-mail every Friday to my students has significantly improved my teaching and more specifically my connection to my students.

The Power of Takeaway E-mails

At first glance the proposal to send a weekly takeaway e-mail to law school students might seem at best unnecessary and at worst patronizing. After all, students in professional schools should be responsible for keeping up with class, completing their assignments on time, and identifying where they do not understand the material or need further assistance. More than that, receiving a newsletter-style weekly e-mail is a technique that many associate with elementary school teachers and local clubs or organizations.

Yet, as a consumer of remote, cohort-based online courses myself, I was surprised to learn that takeaway e-mails were common in online learning environments. These e-mails sent at the completion of class clarified what had been covered, previewed what was to come, and most of all gave me the sense that the instructors cared about my learning process. More than that, these e-mails felt like a free bonus class session that I could complete on my own time. From this experience as a consumer of online education, I decided that these asynchronous touch points would work just as well in my first-year Legal Practice course.

Now, after more than a year of sending weekly takeaway e-mails to my 1L students, I can say with confidence that takeaway e-mails make me a better teacher and, more importantly, help me build greater personal connection with my students for several reasons:

- More Regular Interaction. Students in my class have come to expect the e-mails and refer to them as they would class time. It is a fast, low effort, high impact way of connecting with students three times a week instead of only twice.

- Different Medium. Unlike classroom sessions which are largely conducted orally, the takeaway e-mail allows me to communicate with my students in a different mode of communication, the written word. It is often easier to articulate in writing lessons not just about the products I am asking them to create but also about the process of learning how to create those products. This helps students focus on the metaskills law school seeks to teach them: how to learn, how to deal with new tasks, and how to handle new problems that need to be solved.

- Bigger Picture. The e-mail is a chance to contextualize and crystallize the content covered the prior week and how it fits into the larger trajectory of the course and what is to come. In my experience, students who see this bigger picture earlier are often more successful in the course.

- Less Administrative E-mail. Takeaway e-mails allow me to handle 99% of the administrative and logistical issues that used to consume so much of my time. Instead of receiving and responding to lots of one-off e-mails that get lost in the shuffle, the weekly e-mail provides a one-stop, centralized, and easy-to-find place for reminding students as a class of what we’ve done and what is to come.

- Personal Connection. These e-mails allow me to further connect to students on a personal level. In them I can tell my students what I am working on, why I assigned a certain piece of reading, or even about activities that I am looking forward to on the law school campus. It adds a human touch sometimes hard to convey from the front of a classroom.

- Shorten the Feedback Cycle. If I learn after class that there is a common question or point of confusion based on office hours or individual student meetings, I am able to easily address that question in the weekly e-mail before the weekend begins so that we can start the next session without needing to go backwards.

I have learned from experience that a weekly takeaway e-mail is not only not patronizing to our students, it instead treats them like professional adults and with respect. Instead of sending one-off e-mails whenever I think of something I might want to share, they now look for one e-mail a week with exactly what they need. This allows me to model professional behavior while keeping my students apprised of key information that they need to know in a predictable and concise fashion.

What My Weekly E-mail Looks Like

An effective weekly takeaway e-mail can use any format. That said, the two keys to success in my view are (1) consistent organization and (2) consistent timing. These touchstones allow for takeaway e-mails that are more easy to create and more easy to consume. I personally use our Learning Management System (Canvas) to send the takeaway e-mail as an “Announcement” so that it is sent by e-mail but also stored on the class home page and can be viewed at any time. Each week my e-mail begins with a statement about where the students are in the course (and in their first-year education). This adds context to the educational moment on their journey. It then includes a brief recap of each class meeting in the prior week and a section on the deadlines and topics that will be covered in the week to come. Then it contains additional sections, as needed, about substantive areas that we covered in class, answers to frequently asked questions, or information about exciting events on campus or articles that I want to draw their attention to. To make it easy to read on mobile devices I use section headings with content-relevant emojis so it is easy to skim (for example, ✅ Assignments). And the best part of all is that because the flow of my course is similar year-to-year, large parts of the e-mail can be reused in future years helping leverage that initial investment of time in my future teaching.

But Really? E-mail.

Yes. For better or worse we live in a society in which information is conveyed by e-mail. One benefit is that we can build connections by e-mail that we are unable to build in limited in-person experiences--and those connections can be built asynchronously and from our own homes. We can use this tool as professors in a way that inspires deeper connection and models professional behavior as opposed to a tool that creates a constant stream of ad hoc information. In less than 30 minutes a week, this one technique has allowed me to build deeper connections with my students, spend less time responding to individual questions, and model a culture of learning and accountability in my classroom.