Guest Post: Understanding the Nuances: Diversity Among Asian American Pacific Islanders

Understanding the Nuances: Diversity Among Asian American Pacific Islanders

Understanding the Nuances: Diversity Among Asian American Pacific Islanders

Vinay Harpalani

Henry Weihofen Professor & Associate Professor of Law

University of New Mexico School of Law

Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month recognizes the collective contributions of all AAPIs, but it is also an opportunity to move beyond the collective and highlight the nuanced differences between various AAPI groups. Lumping together all of these groups, without appreciation for their unique histories, experiences, and challenges, can obscure important differences, which in turn reinforces stereotypes. For example, although the “model minority” stereotype depicts AAPIs as high academic achievers from relatively privileged socioeconomic backgrounds, this is only accurate for a subset of the AAPI population. Higher education institutions in particular should highlight the vast diversity among AAPIs, as these institutions place a special value on understanding diversity and are also places where the model minority stereotype is propagated. Yet, when reporting applicant and enrollment data and other metrics, higher education institutions often simply classify their students as AAPI or even just “Asian.” And “Asian” as a singular label is particularly problematic, because it not only obscures differences between AAPI groups, but also conflates the different experiences of new immigrants and international students with those of second- and later generations of Asian Americans. Failure to distinguish these groups exacerbates another stereotype of AAPIs: that we are “perpetual foreigners”—always associated with their ancestral nations rather than with the U.S. Higher education institutions should thus disaggregate their data on AAPI students and be more nuanced in their assessments.

But therein lies the challenging part. There is no consensus on how to classify various AAPI groups or on which groups should be included together. Sometimes, people from different geographic areas of Asia are separated into smaller regional groups. East Asian Americans trace their ancestry to China, Korea, Japan, Mongolia, or Taiwan, while Southeast Asian Americans are descended from Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei, or Timor Leste. South Asian (“Desi”) Americans trace their roots to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan, or the Maldives Islands. Pacific Islanders are descended from Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia—three major island groups in the Pacific Ocean—and are sometimes classified separately from Asian Americans altogether. And although South Asian Americans are formally classified with as Asian Americans, many people do not think of them as such. AAPI student organizations on college campuses illustrate this well, as they can emphasize national, ethnic, or collective identities. In addition to AAPI, other terms include “Asian American”, “Asian Pacific American” (APA), “Asian/Pacific Islander” (API), Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA), and “Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander” (AANHPI).

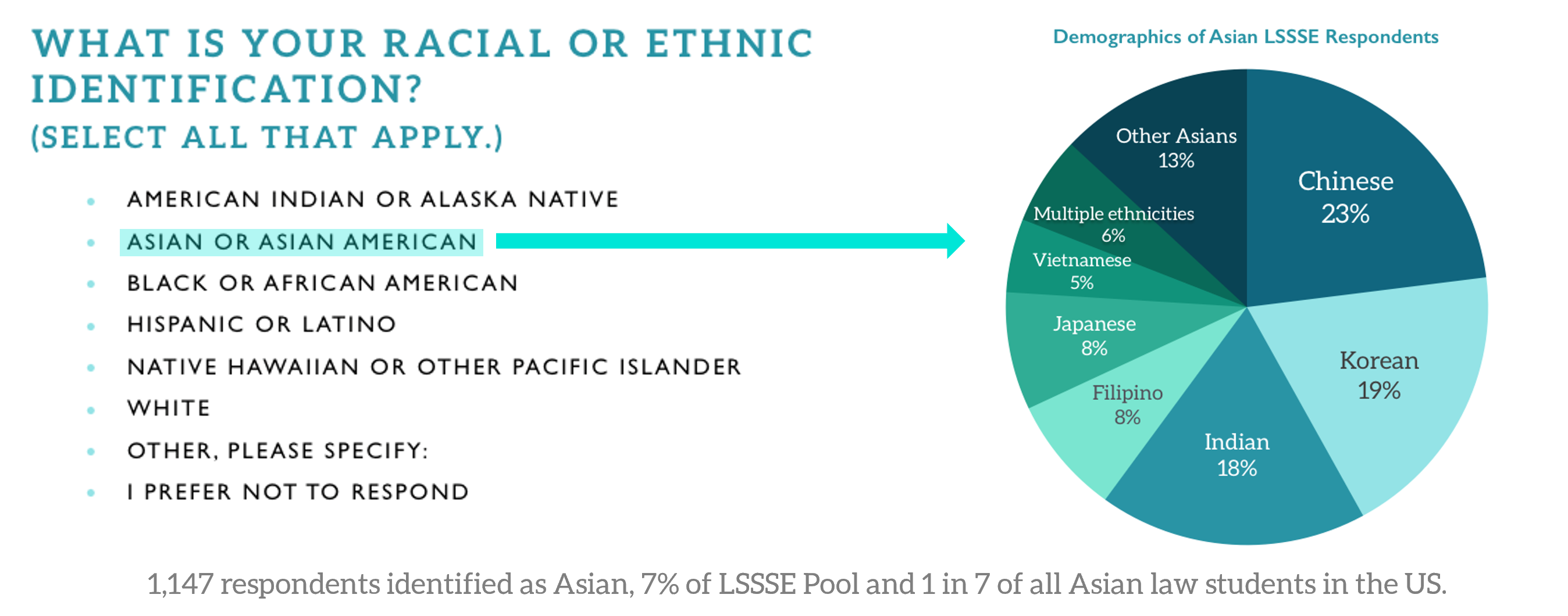

While the broad regional groupings may sometimes be appropriate, grouping by ethnicity or nation of ancestry may better capture the nuances—especially for relatively recent immigrants who left their homelands under particular circumstances, or for international students from particular countries. The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) collects data on diversity among AAPI law students, including differences between domestic and international students. Among its many metrics, LSSSE has disaggregated data on AAPI groups by their nation of ancestry. In its 2016 survey, LSSSE asked AAPI respondents about their ethnicity, and it analyzed this data in its 2017 report on AAPI law students. Overall, 1,147 respondents identified as AAPI: 7% of the total LSSSE pool. Six subgroups comprised at least 5% of the AAPI pool: Chinese (23%); Korean (19%); Asian Indian (18%); Japanese (8%); Filipino (8%); and Vietnamese (5%).

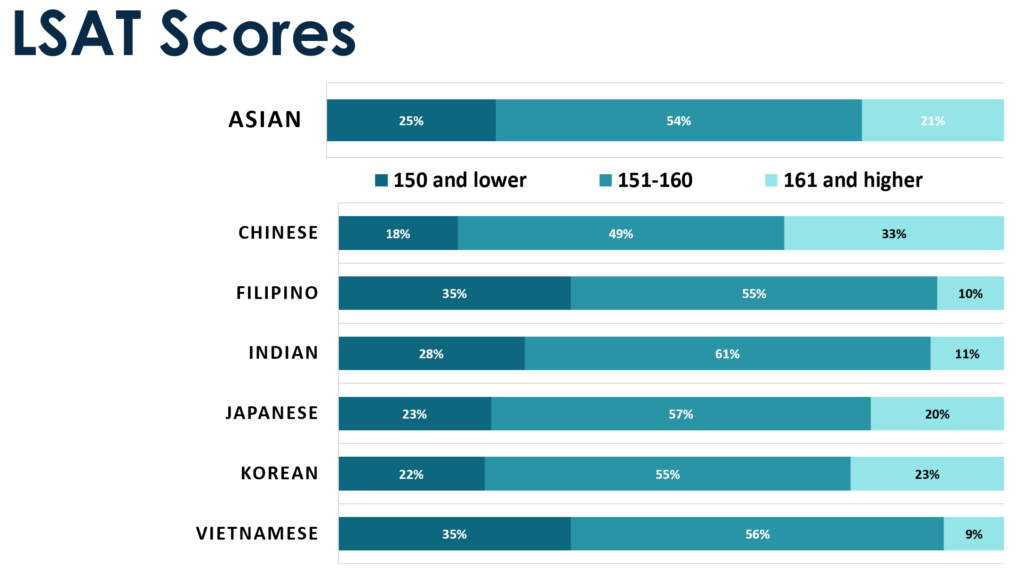

LSSSE’s analysis showed significant differences between these groups. For example, while 81% of Asian Indian American students in the sample had at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree, only 41% of Vietnamese American students did. And although AAPIs generally are stereotyped as high-achieving students, there were also differences in LSAT performance: 33% of Chinese American students in the sample scored 161 (83rd percentile) or higher, whereas only 9% of Vietnamese American students did. These differences may well be related to the immigration histories of these groups. Many Asian Indian and Chinese immigrants to the U.S. came via the occupational preferences of the Immigration Act of 1965, which favored those from educated, professional backgrounds. Conversely, many Vietnamese immigrants came as refugees after the Vietnam War and did not have the same resources. LSSSE’s data also indicate that compared to other AAPI groups, Vietnamese American students were more likely to be working in non-law related jobs, working more than 8 hours per week, and more likely to be providing care to others in their household while they were in law school.

The differences between international and domestic students can also be significant. Students born and/or raised in the U.S. are often socialized very differently than those born and raised in their ancestral nations, and these two groups often have different backgrounds, outlooks, and experiences. Rather than grouping together all students descended of a particular ethnicity, it is informative to distinguish between international and domestic students for each ethnicity. This may be challenging in some circumstances, given the small samples for some ethnicities. In LSSSE’s 2016 survey, 50% of students of Chinese descent were international students, while only 1% of Filipino students were, and proportions of other AAPI subgroups identifying as international students varied widely: 24% Korean; 14% Asian Indian; 8% Vietnamese; and 7% Japanese. Depending on the questions being explored, it may be prudent to focus only on domestic students for some analyses and only on international students for others, and it may be necessary to combine the two for some purposes.

When analyzing the demographics and the academic and social experiences of AAPI students, higher education institutions should follow LSSSE’s lead and disaggregate different groups, and also distinguish between international and domestic students. There is no single, ideal way to classify all of the groups: that will depend on the question and analysis at hand. But paying attention to the nuances will help to dispel the stereotypes that AAPIs are “model minorities” and “perpetual foreigners”—stereotypes that lump different AAPI groups together. And while we can and should celebrate the heritage and contributions of AAPIs as a whole, understanding the nuanced differences between groups is what will truly address the challenges faced by various AAPI communities.

Guest Post: Assessment: How to Do It and How LSSSE Can Help

Assessment: How to Do It and How LSSSE Can Help

Assessment: How to Do It and How LSSSE Can Help

Emily Grant

Professor of Law

Washburn University School of Law

Psst. Have you heard? The American Bar Association (ABA) wants law schools to do assessment.

Of course you’ve heard. We all heard the call to assessment even before the relevant ABA standards (301, 302, 314, and 315) took effect in 2016.

Unlike some, however, I’ve drunk the assessment-flavored Kool-Aid, I’ve got the assessment tattoo,[1] and I’m bringing my flashlight back into the cave to help others with the assessment process. And luckily for all of us, LSSSE can play an important role in institutional assessment activities.

First up, what is assessment? At the most basic level, assessment is evaluation. It is the process of collecting data about student learning and using that data to improve teaching, learning, and indeed the full functioning of a law school.[2]

To that end, the ABA has mandated that a law school must establish a program of legal education and identify specific learning outcomes, or goals, that it is seeking to achieve (Standard 301). Those learning outcomes should include, at the very least, the topics listed in Standard 302, including the knowledge, skills, and values that law school graduates are to possess. The law school should use both formative and summative assessment methods[3] when evaluating students (Standard 314). And Standard 315 brings it all together: the law school administration and faculty “shall conduct ongoing evaluation” of the school and should use the results of that evaluation to make decisions about the future.

The process is designed to help law schools ensure that they, as institutions, are accomplishing their goals and that their students are taking away the things that are most important, as defined by each law school. Within the broad guidelines of the ABA noted above, law schools can prioritize certain knowledge, skills, and values—a social justice mission, for example, or specific professional competencies important to the institution. The assessment process can then expose weaknesses in the curriculum that might allow the important learning outcomes to fall through the cracks, and law schools can adjust accordingly. But the assessment process is also an opportunity for law schools to gather empirical evidence about their strengths and to continue and encourage curricular growth in those areas the students are learning and incorporating well.[4]

The assessment process needs to happen across various levels: institutions, programs or departments, and individual courses. The steps in the assessment process will generally be the same:

- Create student learning outcomes and ensure that the curriculum aligns with the outcomes.

- Design and administer assessment instruments to measure student achievement of those outcomes.

- Review and analyze data that assessment instruments produce.

- Make changes based on the data to improve student learning.

- Repeat the process to evaluate impact of the changes and whether they made any difference in student learning.

Assessment is a cyclical process; it’s iterative in that the data leads to information which can lead to changes in curriculum and instruction which produces new data to analyze. Institutions that merely gather data in spreadsheets will wind up being data rich but information poor. Instead, law schools must use the data “to determine whether they are delivering an effective educational program.”[5] The assessment process is meaningful only when schools use the data “to improve [themselves], to change the curriculum, to change teaching and learning methods, and even to change the assessment methods themselves.”[6]

LSSSE has been a model of effective data-use and frankly, serves as an entire warehouse of granular and big-picture data that law schools can access as part of the assessment process. For example, many law schools have already identified learning outcomes in areas such as knowledge of the law, effective research and writing, oral presentation skills, critical thinking, problem-solving, and professional ethics.

Check out the following questions on the LSSSE survey:

To what extent has your experience at your law school contributed to your knowledge, skills, and personal development in the following areas?

- Acquiring a broad legal education

- Acquiring job or work-related knowledge and skills

- Writing clearly and effectively

- Speaking clearly and effectively

- Thinking critically and analytically

- Using technology

- Developing legal research skills

- Working effectively with others

- Learning effectively on your own

- Understanding yourself

- Understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds

- Solving complex real-world problems

- Developing clearer career goals

- Developing a personal code of values and ethics

- Contributing to the welfare of your community

- Developing a deepened sense of spirituality

That question alone is goldmine of information for law schools to methodically and quantitatively get feedback on the efficacy of the curriculum.

In total, about 60 items in the LSSSE survey map to the ABA standards and interpretations. All participating law schools receive an accreditation report, which could serve as another source of relevant data.

One of my professional roles is Co-Director of the Institute for Law Teaching and Learning, an organization of law school professors across the country (and beyond!) dedicated to improving… well… law teaching and learning. Because we recognize the value of the assessment process in strengthening legal education, we have recently released a comprehensive book discussing the assessment process in detail: Assessment of Teaching and Learning: A Comprehensive Guidebook for Law Schools by Kelly Terry, Gerald F. Hess, Emily Grant, Sandra Simpson (Carolina Academic Press 2021).

In the book, we explain that assessment in law schools can be viewed as a prism. Contained within the prism are principles and practices that apply to various aspects of legal education, including institutional assessment, programmatic assessment, and course-level assessment of student learning, as well as assessment of teaching effectiveness. The book is structured to be a resource in all of those areas. Specifically, it provides a thorough overview of the assessment process generally, and it includes a chapter about how to build a culture of assessment throughout the institution. Next, the book turns to the specifics of assessing student learning in a variety of contexts: at the institutional level, at the course level, and in the context of other programs in the law school, including experiential learning, legal writing, centers and concentrations, co-curricular activities, and non-academic units. Finally, the book focuses the assessment lens on teaching, with a discussion of the fundamentals and suggestions for both summative and formative assessment of teaching performance.

Using data from reliable and trusted sources, such as LSSSE, is important for law schools as they work to evaluate the effectiveness of their curricula. Data from LSSSE can be a valuable resource for law schools as they prepare for review by the ABA Accreditation process. In particular, LSSSE data can be central to a law school’s self-study and strategic planning process by providing focus and opportunities for follow-up. Moreover, LSSSE results are actionable; that is, they point to aspects of student and institutional performance that law schools can do something about. And that, after all, is the entire purpose of the assessment process.

----

[1] Not really, but how nerdy would that be?!

[2] Barbara E. Walvoord, Assessment Clear and Simple: A Practical Guide for Institutions, Departments, and General Education 2 (2010).

[3] Formative assessment is feedback provided during the course with the goal of improving students learning. Summative assessment evaluates student learning at the end of a particular course.

[4] Lori E. Shaw & Victoria L. VanZandt, Student Learning Outcomes and Law School Assessment: A Practical Guide to Measuring Institutional Effectiveness 32 (2015).

[5] Roy Stuckey et al., Best Practices for Legal Education: A Vision and a Road Map 272 (2007).

[6] Id. at 273.

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Deborah Jones Merritt

Distinguished University Professor

John Deaver Drinko-Baker & Hostetler Chair in Law

Much of law school is two-dimensional, confined to the written pages of statutes, regulations, and appellate decisions. Clients appear in our classroom hypotheticals and final exams, but they are cardboard figures designed to illustrate a point or test a legal concept. These cut-out clients lack the backstories, personalities, and secrets that three-dimensional clients embody. Nor do these cardboard clients change their circumstances or modify their goals, as real clients do. While law school is two-dimensional, law practice spreads over all four dimensions of space and time.

How do new lawyers jump from two dimensions to four? Research I conducted with Logan Cornett, Director of Research at IAALS (the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System), suggests that the transition is difficult. Our research team conducted 50 focus groups with new lawyers and their supervisors to explore this transition. Our groups spanned 18 locations nationwide and included 200 demographically diverse lawyers. In addition to their demographic diversity, our focus group members represented a wide range of employment contexts: federal, state, and local government; nonprofits; firms of all sizes, and solo offices. They also worked in more than 50 distinct practice areas, ranging from animal rights to workers compensation.

These focus groups generated more than 1500 pages of transcribed comments, which we analyzed using standard tools of qualitative research. NVivo software helped us organize and code the data; we then followed the principles of grounded theory to draw insights directly from the data. The results overwhelmingly support four conclusions: (1) More than half of new lawyers engage directly with clients during their first year, often as early as the first week. (2) Many of these lawyers also take primary responsibility for client matters. (3) Although some employers offer careful supervision and training, many do not. Instead, many new lawyers operate solo—even when they receive a paycheck from an employer. (4) To practice effectively under these circumstances, new lawyers must possess twelve foundational competencies or “building blocks.”

We discuss these twelve building blocks at length in our report, Building a Better Bar: The Twelve Building Blocks of Minimum Competence. For quick reference, the blocks are:

- The ability to act professionally and in accordance with the rules of professional conduct

- An understanding of legal processes and sources of law

- An understanding of threshold concepts in many subjects

- The ability to interpret legal materials

- The ability to interact effectively with clients

- The ability to identify legal issues

- The ability to conduct research

- The ability to communicate as a lawyer

- The ability to see the “big picture” of client matters

- The ability to manage a law-related workload responsibly

- The ability to cope with the stresses of legal practice

- The ability to pursue self-directed learning

Even a quick glance suggests that many of these building blocks are three- and four-dimensional, rather than two-dimensional. New lawyers must act professionally, not just know the written rules of professional conduct. They must also counsel clients who live multi-faceted lives and who change their goals over time. Understanding legal processes, seeing the big picture of client matters, managing workloads, communicating as a lawyer, and coping with the stresses of legal practice are all three- and four-dimensional tasks.

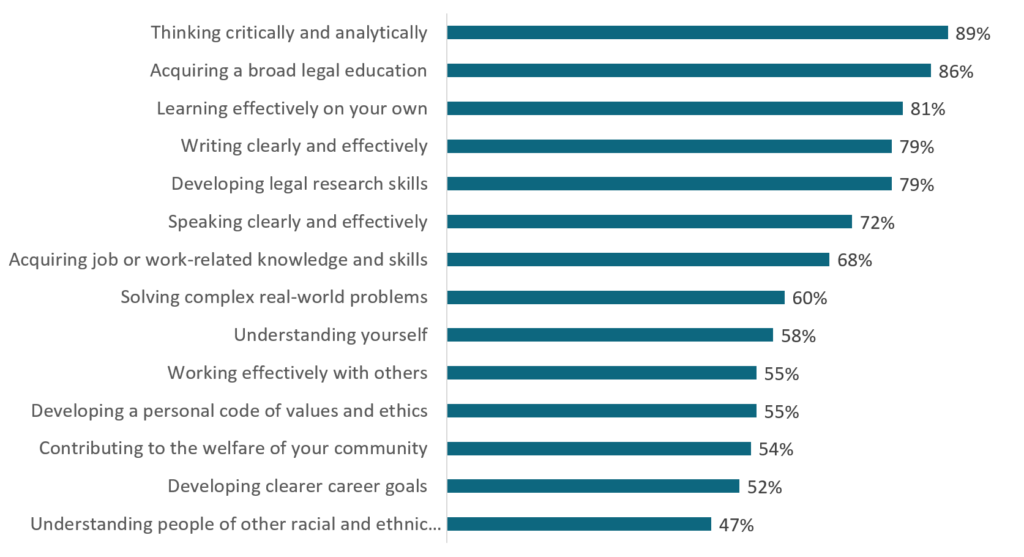

Law schools have made significant progress in teaching students to navigate the complex dimensions of law practice: Clinics and other experiential offerings have expanded over the last 20 years. In LSSSE’s most recent survey, two-thirds of law students reported that their legal education helped them either “very much” or “quite a bit” to acquire job-related knowledge and skills. Sixty percent expressed similar appreciation of law school’s contribution to learning how to solve “complex real-world problems.”

But the LSSSE survey also points to areas of needed improvement. Only about half of respondents believed that law school had helped them “very much” or “quite a bit” in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds, developing clear career goals, shaping a personal code of values and ethics, or working effectively with others. Although phrased differently than our twelve building blocks, these competencies relate to the complex skills we identified in our research.

Once the LSSSE respondents enter practice, moreover, they may be less sanguine about their preparation. Many new lawyers in our focus groups told us that their first year of practice was a “trial by fire.” They struggled to counsel clients, develop strategies, and resolve matters with little supervision. Once on the job, they discovered that they needed more job-related skills than law school provided. Why, they asked, didn’t law school better prepare them for the full range of their work?

Legal educators often say that employers are better suited than professors to teach advanced practice skills. Law school, they argue, properly focuses on teaching basic skills (such as case analysis), threshold concepts, and detailed doctrine. But our research partially disputes that claim. New lawyers undoubtedly need the basic skills and threshold concepts that law school instills. But once they possess those competencies, employers are quite capable of teaching junior lawyers specialized doctrine. Indeed, many new lawyers practice in fields that they never studied. In contrast, employers lack both time and expertise to teach advanced skills like counseling clients, gathering relevant facts, and negotiating with adversaries.

Law school is the place to learn these complex skills. Clinicians and other skills professors know how to teach cognitive skills like counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating. They also know how to provide feedback to novices and coach them to competence. Workplaces offer opportunities to hone professional skills, but schools are the best place to learn the basics.

Some lawyers think of counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating as soft skills that can’t be taught. But there’s nothing soft or unteachable about these skills. They’re harder to teach than the skills we teach in the first-year curriculum, but they’re quite teachable. Think of these skills as the second stage of learning to think like a lawyer. First-year students learn how to analyze legal materials, synthesize those materials, and apply legal rules to hypothetical problems. Those skills lay a foundation for learning more complex skills like counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating. The latter skills require students to add multi-dimensional clients, uncertain legal processes, and shifting fact patterns to their two-dimensional analyses.

If we want our graduates to serve clients effectively, law schools must step into the fourth dimension. Before graduation, every student should learn to counsel clients, gather facts, negotiate, and perform the other multi-dimensional skills embodied in the twelve building blocks listed above. The LSSSE survey can help us continue to track progress on that essential front.

The word "impotence" is considered outdated and is rarely used in modern medical sources. It is used when more than 75% of attempts to get an erection during sexual intercourse end in failure. A more https://www.faastpharmacy.com/ accurate and modern term is "erectile dysfunction", which describes a variety of problems in bed in young and mature men.