Guest Post: Empirical Sociolegal Research and the Use of LSSSE Data

Guest Post: Empirical Sociolegal Research and the Use of LSSSE Data

Ajay K. Mehrotra

Director & Research Professor

American Bar Foundation

Shih-Chun Chien

Research Social Scientist

American Bar Foundation

Thanks to Meera Deo and everyone at the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) for the opportunity to contribute to the blog. As most readers of this blog know, LSSSE provides a unique and in many ways unparalleled dataset on the law student experience across both time and place. Simply put, LSSSE is a treasure trove of valuable data for scholars studying legal education and the legal profession, as well as for law school administrators seeking to learn more about the law student perspective. In previous blog posts, several of our American Bar Foundation (ABF) colleagues have described how their long-term empirical and interdisciplinary research projects have benefited from access to LSSSE data. In this post, we would like, first, to underscore what makes LSSSE data special and valuable for empirical, sociolegal scholars studying legal education and the profession. Second, we describe the ABF and what sets it apart as a non-profit, non-partisan, independent research institute focusing on law. Finally, we conclude by discussing a recent ABF project on diversity and inclusion that leverages LSSSE data to explore law student career preferences and expectations about judicial clerkships.

The Uniqueness of LSSSE Data

Last year marked LSSSE’s 15th year anniversary. In that decade and a half, LSSSE has collected responses from over 370,000 law students from roughly 200 law schools across the United States, Canada, and Australia. Survey respondents represent a broad cross-section of law students from a variety of law schools and countries. What began in 2004 as a modest research project at the Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research has successfully evolved into the largest dataset of law student survey responses in existence. LSSSE’s annual survey results provide law schools and researchers with a unique, comparative perspective on student views and perceptions, allowing administrators to see how student attitudes at their school might correspond with and differ from peer schools and national averages.[1] Likewise, because LSSSE provides longitudinal data, using nearly identical questions in surveys over time, consumers of LSSSE data can measure continuity and change in student perceptions and beliefs. In short, the scale and scope of LSSSE data is remarkable.

There are, to be sure, other organizations that collect data about legal education and law students. The American Bar Association (ABA), the National Association of Law Placement (NALP), and individual law schools themselves gather a tremendous amount of information, from admissions statistics to employment placement numbers. And some law schools survey their own students about their educational experiences. But LSSSE, as our ABF colleague Stephen Daniels notes in his blog post, provides not just information about students but information directly from students. The surveys give students a voice.

In addition to generating distilled data from its annual survey, LSSSE also provides an invaluable service by publishing highly accessible annual reports. By translating social science findings into lay terms, LSSSE researchers highlight particular themes and patterns about the law student experience based on survey results. In recent years, annual reports have examined the challenges and opportunities faced by women law students; the importance of relationships with faculty, staff, and fellow students; and student employment preferences and expectations, among other significant topics.

ABF Empirical Research

LSSSE data and reports are particularly salient for the type of empirical and interdisciplinary research conducted at the ABF. Established in 1952 as an independent non-profit, non-partisan research organization, the ABF is among the world’s leading research institutes for the study of law, legal institutions, and legal processes. Among the ABF’s three main areas of research, the one that is most closely connected to LSSSE is our work on “Learning & Practicing Law.”[2] Within this research portfolio, we have several ABF scholars who are investigating an important array of legal education topics, from Stephen Daniels’s study of student assessments of law schools to C.J. Ryan’s work on the financing of legal education. Each of these rigorous and sophisticated empirical research projects is examining long-term trends in legal education – trends that can only be identified and analyzed with the type of data administered by LSSSE.

LSSSE data complements the ABF’s core research mission. The data help scholars, at the ABF and elsewhere, address some of the most pressing issues facing the legal system, including legal education. To tackle empirical questions about the quality, value, and impact of legal education, for instance, one must have access to data – data about how students have perceived and responded to their law school experiences. One new ABF research project that harnesses LSSSE data in this way is our study of diversity and inclusion (or lack thereof) in judicial clerkships.

The ABF’s Recent “Diversity and Judicial Clerkships” Project

In 2019, the ABF launched a new project (Portrait Project 2.0) exploring how Asian Americans are situated in the legal profession. This new ABF research follows up on an earlier study (A Portrait of Asian Americans in the Law) led by the Honorable Goodwin Liu of the California Supreme Court, in collaboration with Yale Law School and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (NAPABA). The ABF-led Portrait Project 2.0 delves deeper into the many challenges and opportunities faced by the Asian American legal community. The project aims to understand the factors that shape the careers of Asian American lawyers. One of the aims is to understand why Asian Americans are not reaching the upper echelons of the profession – from judicial clerks, to law firm partners, to top prosecutors and judges, to law school deans and non-profit executives.

As part of Portrait Project 2.0, ABF researchers and collaborating scholars are investigating why women and minority law students do not secure clerkships in proportion to their numbers at top law schools. Existing literature on judicial clerkships has identified the persistent lack of gender and racial diversity in federal judicial clerkships.[3] Despite the growing interest in diversity and inclusion in the profession, we currently lack a fundamental, baseline understanding of different components of the judicial clerkship “pipeline.”

Before we can provide answers to some of the diversity challenges, we must identify and analyze the factors that have facilitated or frustrated the goals of diversifying judicial clerkships. We believe there are at least three critical mechanisms that contribute to the disparities in judicial clerkships: (a) self-selection by students based on personal preferences, perceptions, family expectations, occupational choice, or ambient signals; (b) advising and mentoring by law school faculty, staff, and administrators; and (c) selection by judges.

Because LSSSE provides longitudinal data on race and gender, and students’ career preferences and expectations, its value to our project is twofold. First, it provides an empirical baseline of overall student perceptions versus expectations. A recent LSSSE annual report, for instance, demonstrates that judicial clerkships are frequently more aspirational than expected career goals, especially for women and minority students. Second, LSSSE highlights the imminent need for original data about the institutional support mechanisms for law students, including how law schools track, advise, encourage, and mentor students interested in pursuing judicial clerkships.

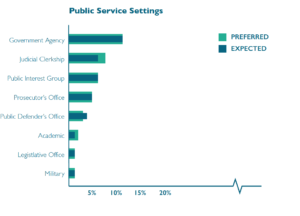

Generally, clerkships are an appealing career path for those law students interested in working in “public service settings.” According to a recent LSSSE annual report, among the 36% of law student respondents who preferred to work in a “public service setting,” obtaining a judicial clerkship was the second most sought after public setting, behind “government agency” and ahead of “public interest group.” Perhaps more saliently for our nascent study, the survey also found that there was a significant spread between respondents’ “preferences” for a clerkship and their “expectations” that they would secure such employment – a spread that was larger than any other public service settings. This suggests that law students overall believe that a clerkship is frequently an aspirational goal [see Chart 1].

Chart 1: Proportion of Respondents Preferring and Expecting Public Service Settings

The LSSSE report also highlights how race and gender play an important role in career preferences and expectations. The 2017 report found that White and Asian American students preferred judicial clerkships more than other racial groups. The overall picture on gender differences was even more pronounced. Not only did men prefer judicial clerkships more than women; when it came to career expectations, men continued to have judicial clerkships as their second expected public setting, whereas for women, judicial clerkships dropped out of the top three public setting career expectations. Our ABF research team is in the process of analyzing subgroup differences and more recent LSSSE data on career preferences and expectations to measure more precisely the gap between preferences and expectations and to explore whether these beliefs have continued or perhaps changed over time.

Conclusion

In sum, LSSSE data is an extraordinary asset for a vast array of research questions about law student preferences, expectations, and experiences. With its student-centered approach and rigorous design, LSSSE has advanced our understanding of numerous aspects of legal education and the profession. Still, LSSSE remains an underutilized source for serious and sophisticated empirical, sociolegal research. While many ABF scholars have been mining LSSSE data for the past decade, there is much more that other researchers could be doing with LSSSE. Our recent ABF project on diversity and judicial clerkships is just one modest example of how LSSSE data can be leveraged to tackle some of the most pressing concerns facing legal education and the profession. We hope other empirically oriented scholars will join us in engaging with, and making use of, LSSSE data.

____________________

[1] In a recent LSSSE blog post, American University Washington College of Law Dean Camille Nelson accurately referred to such use of LSSSE as “data-driven deaning,” available at: https://lssse.indiana.edu/blog/guest-post-towards-data-driven-deaning/.

[2] The ABF’s three core areas of research are: (1) Learning & Practicing law; (2) Protecting Rights and Accessing Justice; and (3) Making & Implementing Law. For more on the ABF’s research mission and examples of its research please visit the ABF website at: http://www.americanbarfoundation.org/index.html.

[3] NALP, “Bulletin: Increasing Diversity of Law School Graduates Not Reflected Among Judicial Clerks” September, 2014, available at: https://www.nalp.org/0914research; Danielle Root, Jake Faleschini, Grace Oyenubi, “Center for American Progress: Building a More Inclusive Federal Judiciary” October 3, 2019, available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/courts/reports/2019/10/03/475359/building-inclusive-federal-judiciary/; Todd Ruger, “Law.com: Statistics Show No Progress in Federal Court Law Clerk Diversity” May 2, 2012, available at: https://www.law.com/nationallawjournal/almID/1202551008298&Federal_courts_making_no_progress_regarding_law_clerk_diversity_numbers_show/.