The Parenting Penalty for Law Students

Laila L. Harris

Laila L. Harris

Associate Professor of Law & Co-Director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic

Associate Provost of International Affairs

Tulane University Law School

This fall, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory on the mental health and well-being of parents, responding to levels of high stress parents report and the harmful effects on their own mental health, as well as their children’s. This was on the heels of findings from a national study that a majority of parents experience isolation, loneliness and burnout related to parenting. For those of us at law schools, often recognized as high stress environments already, it raises the question: what is the landscape for parents in law schools?

Professor Lindsay M. Harris (University of San Francisco Law School) and I have begun talking and writing about “the parenting professor penalty,” the panoply of harms and challenges that pregnant and parenting people, as well as those who are presumed to become pregnant or parenting, face in entering and being successful as faculty within the legal academy. We are bringing this topic to the annual AALS meeting, focused on “Courage in Action” held in January as a discussion group session and welcome you to join us. Yet faculty often comprise those with the most privileged positions in law schools, relative to staff and students. Law students who are parents, or more broadly caretakers, may face steep challenges and inequities related to their status and circumstances.

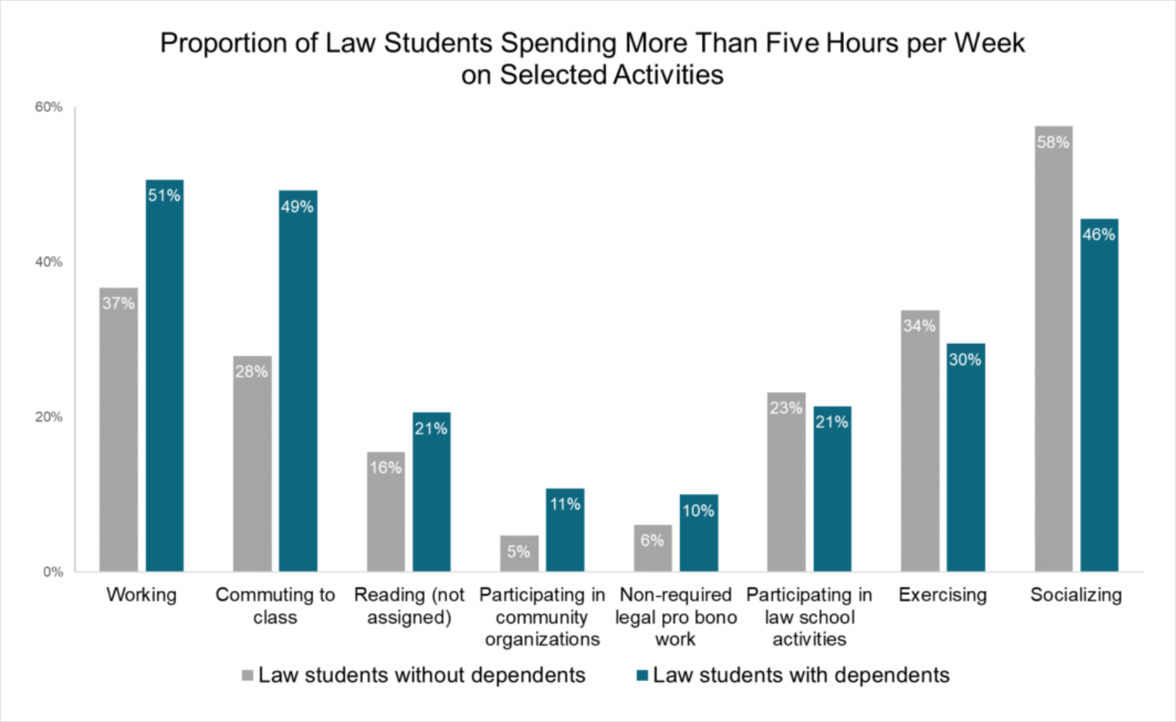

Mental health has long been a concern in law schools and the legal profession. According to LSSSE, around 60% of law students experience very high law-school related stress or anxiety. Law students who also serve as caretakers are particularly likely to have more stress. This is especially true because students with dependents also spend more time on commuting to class and working, and less time on exercising and socializing, which may help combating anxiety and isolation.

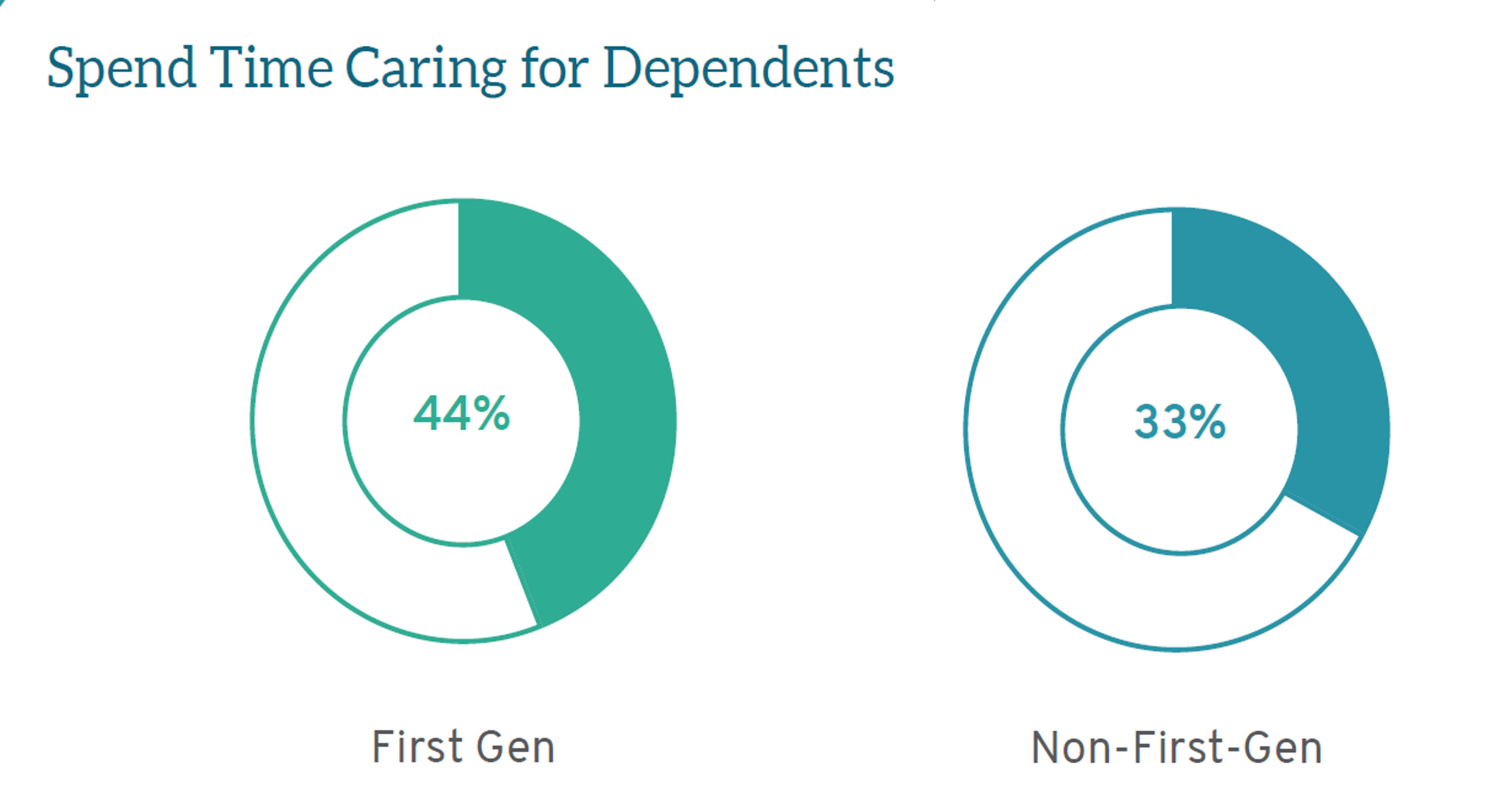

While about one-third of law students reported spending time caring for dependents, the burden of hours spent every week is particularly high for non-traditional law students. First-gen students comprise a larger portion of law student caretakers: 44% of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

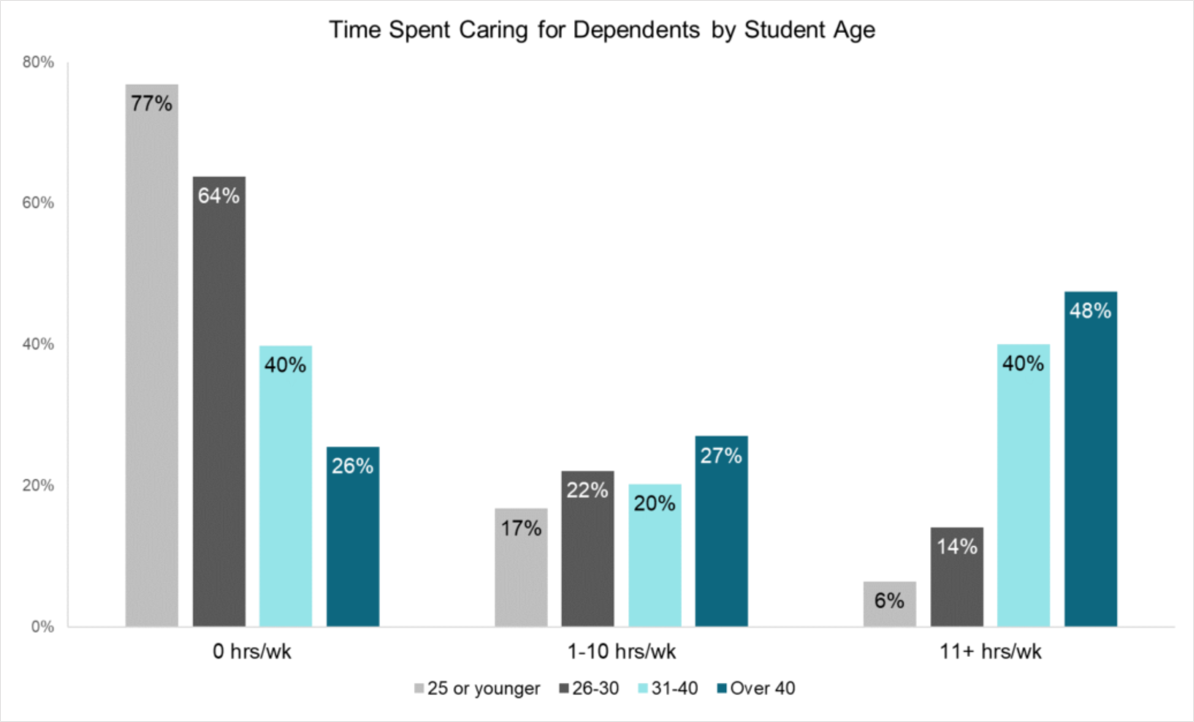

Caretakers are also over-represented in part-time law programs, with 56% of part-time students reporting caretaking for dependents. Time spent caretaking per week is highest for older law students, as 40% of those aged 31-40 spent 11 or more hours per week caretaking, and nearly half of those aged over 40 spent 11 or more hours caring for dependents.

Given these genuine concerns for law student caregivers, how can we as law faculty respond individually and collectively, and how can we respond institutionally as law schools?

As individual actors, law professors should think about how to account for the stresses parenting law students may be facing. Professor Harris and Professor Mallika Kaur recently released a co-edited volume titled How to Account for Trauma and Emotions in Law Teaching, which is instructive and helps to mainstream conversations about stress and well-being within law schools. Professors may, for example, want to think about whether they want to model “parenting loudly,” though this is not without varying consequences depending on an individual professor’s positionality, as Professor Meera E. Deo documents in her book Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia.

How can law schools as institutions respond to the special needs of law students who are caretakers and are at risk of heightened stress and burnout? As part of the ABA mandate that law schools provide substantial opportunities to explore “well-being practices,” law schools should offer meaningful courses and co-curricular activities to address law students’ well-being, including trainings, screenings, and policies to encourage work-life balance. These co-curricular programs should also have resources to address the particular needs of law students who are parents or caretakers. Some institutions do this already. For example, some schools have created a clearinghouse of information directing students to school and city-specific parenting resources, as well as child care subsidies and student groups.

Schools should also conduct internal assessments to learn about the experiences and needs of law students who are caregivers to consider whether policies and practices around leaves and broader resources for this community are responsive to needs. Creative responses including creating parenting support groups are warranted. Schools can also take steps to accommodate the schedules for working parents. For example, one law school designated one of the nine first year small section modules as the parent module (affectionately called the “mommy mod”) and classes were scheduled to align with times when school was open and to accommodate drop off and pick up responsibilities. Similarly, another school designed a part-time law program so law students with school age children take coursework while their children are in school. Finally, as a broader measure and perhaps an impetus for the cultural shift the moment demands, U.S. law schools should consider signing on to the International Guidelines for Wellbeing in Legal Education, which would require a comprehensive overhaul of law school structure, curriculum, and atmosphere with well-being in mind.

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Christopher J. Robinette[1]

Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

In the fall of 2023, Southwestern Law School received ABA approval to operate the country’s first fully online Juris Doctor program. Moreover, to increase student flexibility, the program is asynchronous, with only a few voluntary synchronous sessions. In essence, the students and professor will not be online together in a Zoom room, but students will access videos of the professor and exercises on their own schedules.

As a law professor who has taught in-person courses for over twenty years, I deliberated a long time before volunteering to teach online. I love the energy of the face-to-face classroom and, frankly, I was somewhat skeptical about the efficacy of online law classes, particularly in the first year. In fact, one of the most compelling reasons that I agreed to teach online was the hope of improving my pedagogy in the “real” classroom. As I began planning my online course, however, I became excited about the possibilities particular to the online mode.

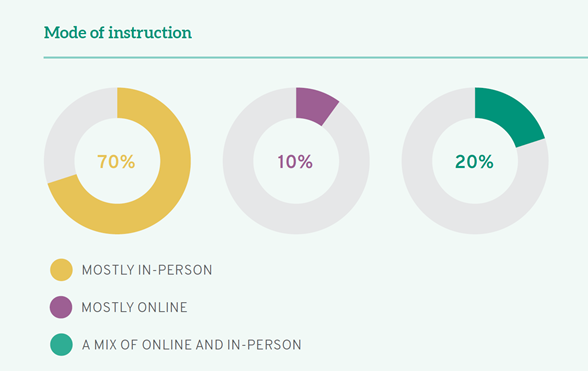

The 2022 LSSSE Annual Report, Success with Online Education, says half (50%) of all law students were enrolled in at least one course that was taught mostly or entirely online and every law school participating in the LSSSE survey offered at least some online courses. Most law students (70%) took courses that met in-person, though 10% took mostly online courses, and 20% reported that they had enrolled in a mix of courses that met online and in-person. Of those who did meet online, most (78%) were in synchronous classes; but 3% of LSSSE respondents in online courses met asynchronously and an additional 19% were in hybrid courses. Clearly, online education is here to stay and could grow even more prominent in the years ahead.

As an instructor, my biggest concern about teaching online was something about which LSSSE is expert: engagement. Keeping students engaged can be difficult under any circumstances, but it is especially challenging online. I believe a solution to the online engagement problem is not singular; instead, it lies in numerous program and instructional design decisions. With that in mind, I considered how law professors engage their students, particularly first years, in the traditional classroom. Of course, a major technique is the Socratic method, in which the professor asks a (usually cold-called) student increasingly challenging questions about a case. This is an interactive mode of teaching and learning that involves the students and does not conceive of them as passive recipients of knowledge. Although they exist, I do not need the overwhelming data telling me that active learning is superior. I can sense it in the fact that the air starts to go out of the room whenever I lecture my students for lengthy periods of time.

Was there a way to adapt the Socratic method to the online asynchronous environment? In thinking about this, I had to admit that one facet of the Socratic method in the classroom was not replicable. In the traditional classroom, the professor is able to tailor her follow-up questions precisely to the student’s answers. This is not possible in an asynchronous online class. But—and this is where I grasped that the online environment has advantages—you can ask all of the students all of the questions. In the traditional classroom, one student is on call. Ideally, we expect the other students to be following along and answering the questions silently for themselves. In reality, we know that at least some of them do not. They are spaced out, or shopping online, or simply exhausted. In an online course, all students can be engaged. And it can be verified.

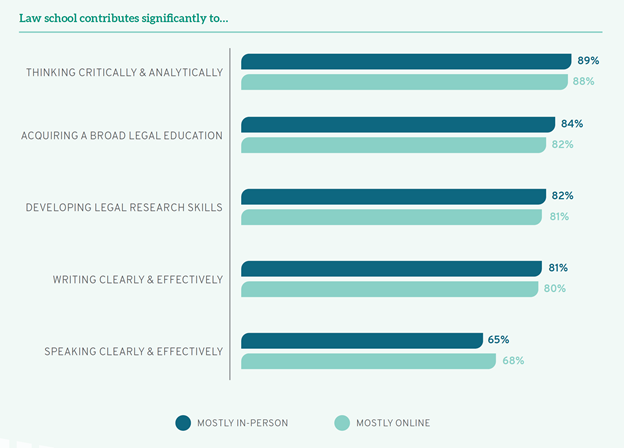

This is how I developed the Universal Socratic for my online course. For each module in my course, I selected one case that I found significant and created an interactive exercise around that case. I wrote five questions about the case. For the first few modules, I followed the structure of a basic case brief (facts, issue, holding, disposition, rationale), allowing the students to reinforce their briefing skills. As the modules progressed, I formulated more questions in the upper ranges of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analyzing, evaluating, and creating). Thanks to exercises like this, LSSSE data indicate that students believe legal education contributes to multiple skills, especially thinking critically and analytically, as much online as in-person.

I then drafted answers to the questions. Using Canvas’s Quizzes feature, I inserted the questions and required the students to answer them one at a time. After the student has answered each question, and before they answer the next question, they are shown my answer and are able to compare it to theirs. Not only asking the questions but providing prompt feedback is helpful to engage students. Using this process, the student and I are essentially having a dialogue, even though I do not have the benefit of their exact answer in real time in person. Moreover, every student in the class engages in the exercise of answering the questions.

Given the growth in online education, students will benefit from legal educators modifying effective face-to-face techniques, like the Socratic method, for the asynchronous online mode. When educators do so, they will find that some features of online education make it better than the original.

[1] I benefited greatly on this project from the ideas of my terrific colleagues Catherine Carpenter, John De Sousa, and Danni Hart.

The Role of Data in Mission-Focused Law School Leadership

The Role of Data in Mission-Focused Law School Leadership

Jelani Jefferson Exum

Dean & Rose DiMartino and Karen Sue Smith Professor of Law

St. John’s University School of Law

I am a mission-focused leader. Of course, many law school deans would describe themselves in the same manner. Every law school has a mission that identifies and guides the institution. Most law deans were drawn to law school leadership because we believe in the transformative power of legal education, but also because we believe in the mission of our institution. That is my story. As the new Dean of St. John’s University School of Law, I am inspired and guided by the mission of the law school. The mission of St. John’s Law focuses on providing access to an excellent legal education for a diverse student body; teaching and scholarly innovation; building an antiracist community; inspiring civic engagement; and developing leaders. I realize that in order to lead the law school in a manner that stays true to this mission, I need to have an in-depth and nuanced understanding of our student body and their experiences. The data provided by LSSSE are a powerful tool for any law dean – especially one new to an institution – to learn about their student population and the broader legal education landscape. That data, in turn, can assist a dean in supporting the mission of the school.

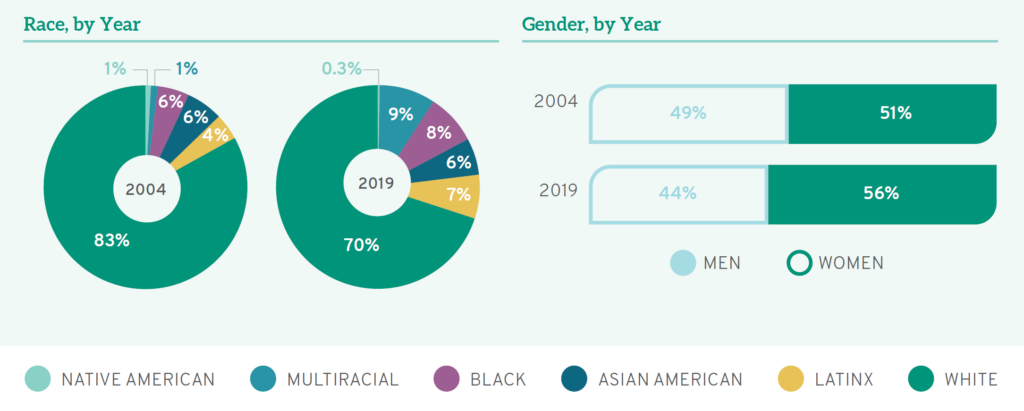

There may have been a time in legal education when staying true to mission was an easy task. That certainly is not the case in today’s educational and legal climate. For instance, for nearly 100 years, St. John’s Law has opened its doors to a diverse student body – many of whom were first generation college or law school students – and provided them with access to a legal education that would transform their economic mobility. This focus on making legal education more accessible to a diverse group of students, which has been a hallmark of St. John’s Law, is increasingly challenging. The recent constraints placed on admissions by the Supreme Court means that fulfilling this diversity mission priority requires more intentional work on the part of law school deans and their admissions teams. LSSEE’s longitudinal data, such as that provided in The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, provides important information on the shifts in the demographics and needs of law students over the years.

The data summaries are very detailed and break out certain results based on students’ race, gender, sexual orientation, and age. These statistics can aid in understanding the evolving expectations of students in ways that can also inform methods of communicating your school’s value and strengths to a diverse body of prospective students.

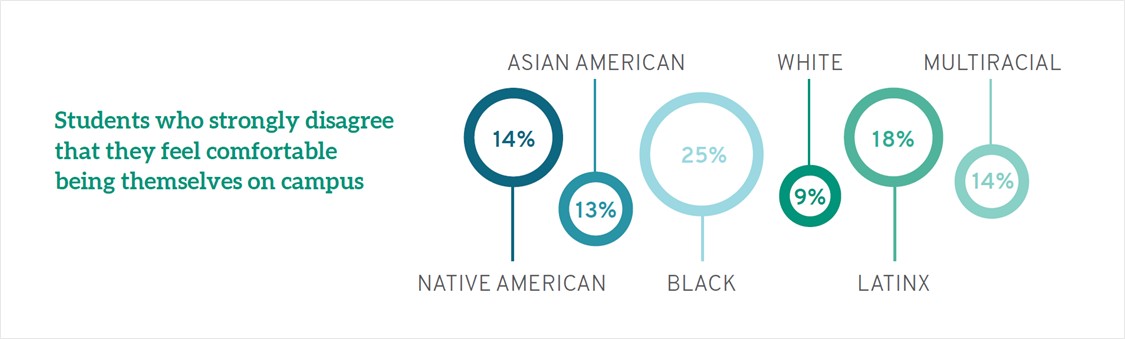

Understanding a diverse student body is not only important in maintaining a mission of access, it is also vital to schools that are working to stay true to an antiracism mission. LSSSE data has been extremely useful in illuminating the culture of law schools. Specifically, the 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, provides in-depth information on a variety of topics that give insight into the student experience, from institutional support, to belonging, to diversity skills.

Before I became dean, St. John’s Law used this report, in addition to other school-specific data, to inform the development of its annual Anti-Racism Day programming for 1L students. Now that I have joined as dean, this type of LSSSE data has helped me to think through, not only admissions challenges, but various aspects of our school where the effects of institutional racism can be investigated and addressed – from assessments to student services to teaching strategies. This information also helps us to measure the success of our commitment to an innovative application of knowledge. We will continue to use LSSSE reports as an indirect measures of student success and competence in our learning outcomes. LSSSE survey results give us a mechanism to learn what students think about their learning and experience in law school to use in concert with our more direct assessment measures. In this way, LSSSE data are valuable across mission goals, tying together the points relevant to antiracism, student learning, and overall student success and well-being.

Today’s law school has more need than ever to draw upon its mission statement to chart a path forward. There are many pressures and changes in legal education that make it easy for a school to lose its way. From addressing issues of free speech and academic freedom in light of concerns regarding student inclusion and belonging to navigating how to embrace and champion diversity and access within new legal limits --a law school can easily veer off target and lose its foundational values. LSSSE and the data it so thoughtfully collects and disseminates can be a powerful tool in staying the course for a mission-focused leader.

Improve the Diversity of the Profession By Addressing the Costs of Becoming a Lawyer

Improve the Diversity of the Profession By Addressing the Costs of Becoming a Lawyer

Joan Howarth

Professor Emerita, Boyd School of Law, UNLV

Dean Emerita, Michigan State University College of Law

One of the themes of my book, Shaping the Bar: The Future of Attorney Licensing (Stanford University Press 2023), is that becoming a lawyer in the United States is too expensive. Unlike in many other countries, the U.S. law degree typically requires three or four years of expensive postgraduate study, which should be enough time to produce and assess minimum competence to practice law. But after graduating from law school bar candidates typically spend two more months and thousands of dollars immersed in bar prep with a commercial company. The billion-dollar bar prep industry covers the gap between what was learned in law school and what is required to pass a bar exam. Student loans do not cover the cost of those bar prep courses or the living expenses while preparing for the exam. Law graduates without financial resources face financial emergencies – or time-consuming jobs for paychecks -- when they are supposed to be using all their time preparing for the bar exam.

Not surprisingly, then, research shows that economic assets are a significant factor in bar passage. And LSSSE research shows us the connections between the excessive expense of becoming a lawyer and the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in bar passage rate.

The racial and ethnic bar passage disparities are extreme. For example, the national ABA statistics for first time passers in 2023-24 show White candidates passing at 83%, compared to Black candidates (57%) with Asians and Hispanics in the middle (75% and 69%, respectively).

These disturbing figures are very related to the expense of becoming a lawyer.

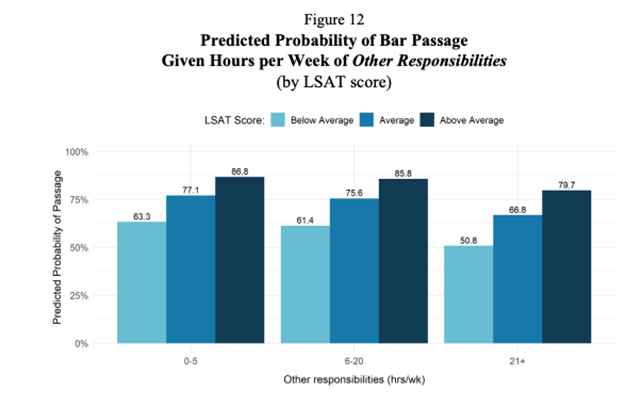

The 2021 National Report of Findings for the AccessLex/LSSSE Bar Exam Success Initiative showed that law grads who take care of children or work in non-law jobs have a harder time passing bar exams.

These problems were confirmed in a large 2021 study of New York bar takers. Even after controlling for LSAT and other academic factors, law grads who had greater financial resources were significantly more likely to pass but grads who worked for pay were significantly less likely to pass.

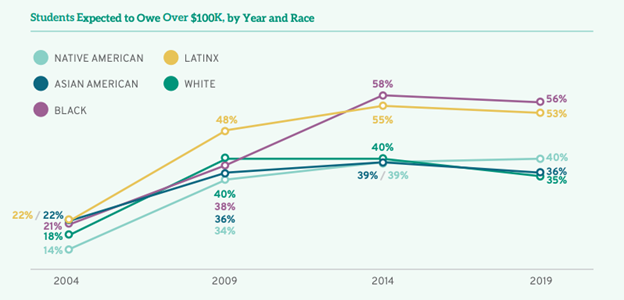

Who are the law grads with fewer financial resources? LSSSE research shows us that Black and Latinx students are carrying more law school debt than White students.

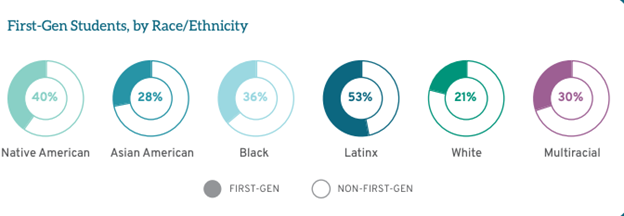

LSSSE’s 2023 Annual Report focused on first-gen law students shows that law students who are the first in their families to graduate from college are more likely to be from underrepresented communities.

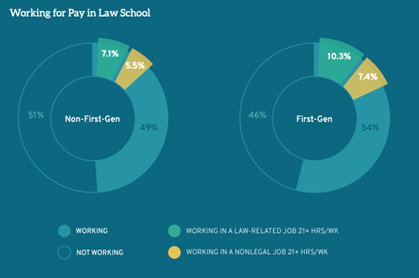

First-gen students are also more likely to work for money and work in non-law related jobs in law school.

LSSSE data from that report show that first-gen law students are also more likely to care for dependents.

In other words, law graduates who could be great lawyers—too many of whom are people of color, first-generation law students, and parents—are failing bar exams because they cannot drop everything else for two months to devote themselves to memorizing thousands of rules, most of which they would not use in practicing law, and most of which they will forget quickly after walking out of the exam.

Finally, though, after decades of stability -- or stagnation -- in attorney licensing, change is here. And some of the changes, such as the new pathway to licensure in Oregon based on supervised practice instead of a traditional bar exam, or the Nevada Plan in which most of the requirements can be satisfied during law school, should significantly decrease the costs of licensure and add flexibility for candidates with responsibilities beyond studying for a bar exam. These reforms are long overdue.

Closing the Information Gap for Law Students Interested in Public Interest Careers

Verna L. Williams

CEO

Equal Justice Works

Our nation is experiencing an access to justice crisis. According to the Legal Service Corporation, 92% of low-income people’s civil legal needs went unmet in 2022, leaving a massive gap in our justice system. What’s more, the number of lawyers focusing on underserved populations is very small. According to the American Bar Association, fewer than one percent of lawyers are paid legal aid attorneys. As law schools plan for the coming academic year, I urge them to consider how to address this untenable gap in our legal system.

Put simply, creating lasting change for communities and in our justice system requires more graduates to choose public interest law. The fact that so few law graduates pursue this route is not only problematic, but also puzzling. As a law school dean, I saw first-hand that many aspiring attorneys chose legal education because they wanted to serve the public. In my new position as CEO of Equal Justice Works, a nonprofit that connects law students, law school professionals, lawyers, and advocates with fellowships at legal services organizations and other opportunities in public interest law, we are tackling this problem head on.

Consider student loan debt. AccessLex reports that, on average, law students borrowed $157,300 last year. Students of color graduate with an average educational debt twice the amount of their white classmates. With entry-level public interest attorneys earning a median $63,200, compared to $200,000 for law firm associates, it’s hardly surprising that so many graduates would choose private practice.

What else explains the dearth of public interest attorneys? To answer that question, Equal Justice Works partnered with the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), an invaluable resource, to identify blind spots in supporting future public interest lawyers. Working with LSSSE, we crafted questions for the 2023 LSSSE Survey to help quantify just how accessible information about pursuing public interest law is for law students across surveyed law schools.

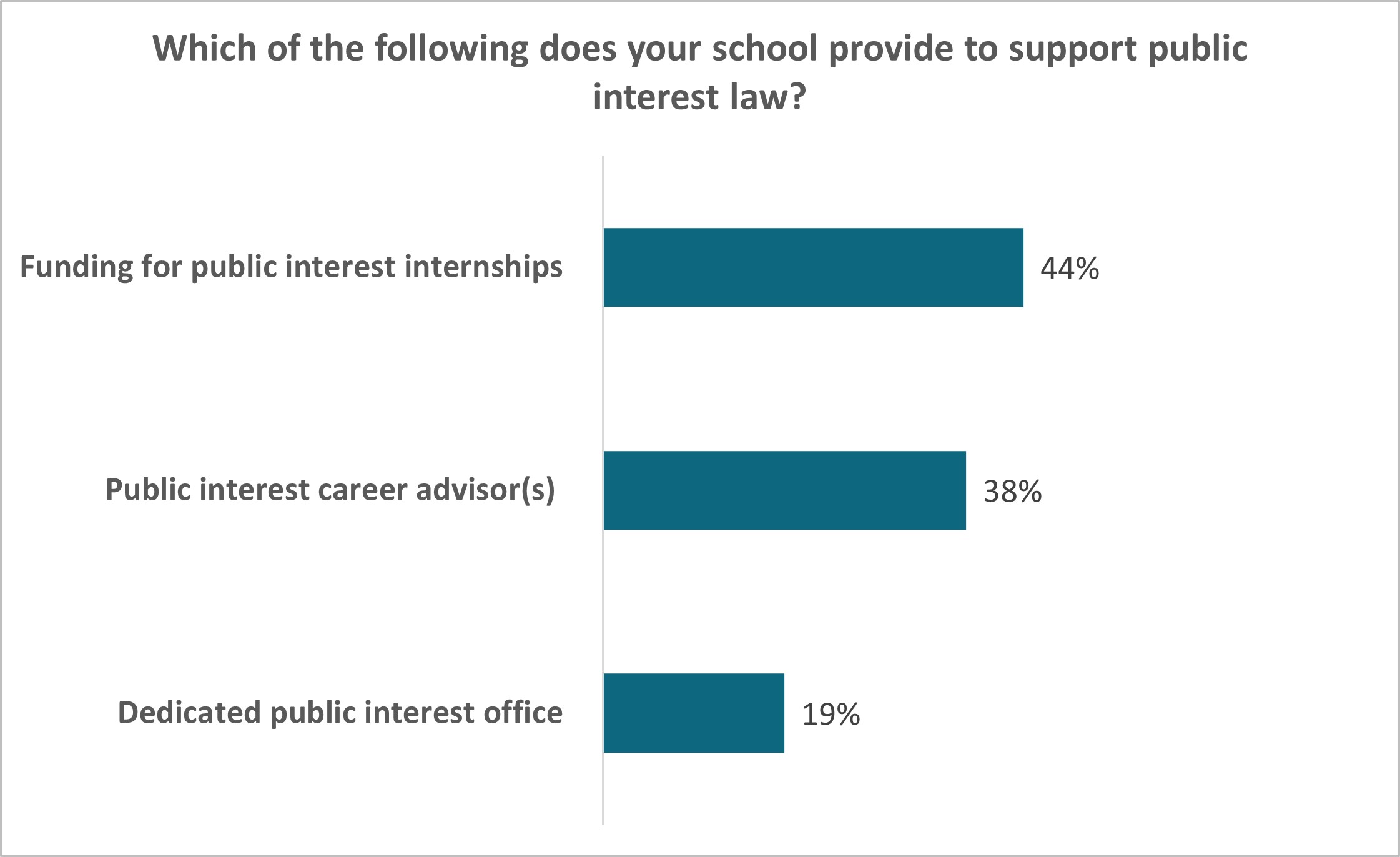

The results illustrate that many opportunities exist for legal education to build or strengthen support for new public interest lawyers. Among the findings:

- Only 44% of participating schools provide funding for public interest internships.

- An even smaller percentage of schools, 38%, employ public interest career advisors.

- Just 19% of law schools have a dedicated public interest office.

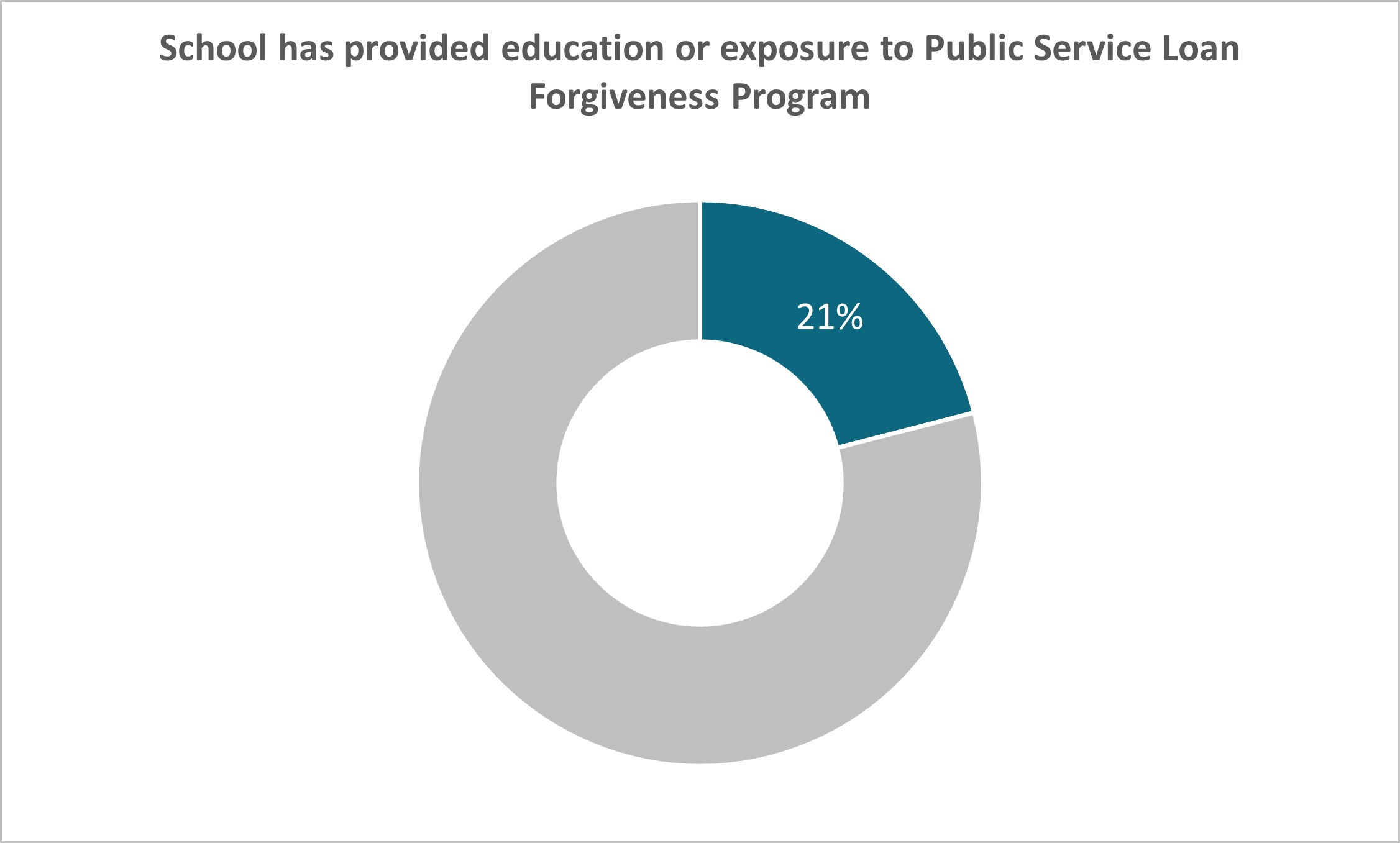

- When asked whether their school provided education and exposure to tools like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), the answer was a disheartening 21% responded in the affirmative.

The result is a knowledge gap about how to make the most of existing resources that can make pursuing public interest feel less like fantasy and more of a reality.

The LSSSE survey results strike a chord in me. Like today’s students, I chose law school because I wanted to make a difference. But before I began my public interest journey, I practiced in BigLaw to get my financial house in order—when I graduated, loan repayment assistance plans were brand new. I was able to get settled with my associate’s salary, paid off some debt, and never looked back.

My debt was considerably less than that of today’s student – but no less frightening. I wouldn’t trade my trajectory for anything, having had the privilege of practicing at the Department of Justice and the National Women’s Law Center. I built on those experiences as a faculty member at the University of Cincinnati College of Law (UC), in part, to create and support the next generation of feminist legal advocates. As a faculty member, I co-founded and co-directed the Nathaniel Jones Center for Race, Gender, and Social Justice, through which we created a clinic, advised students seeking public interest fellowships, and put on programs about how to “make a difference while making a buck.” Serving as dean of the law school allowed me to facilitate other efforts to make public interest opportunities available to students. I’m especially proud of the partnership we engaged in with Hamilton County Municipal Court to create the Help Center, which provided assistance to unrepresented litigants. Staffed by a UC attorney, the Help Center engaged students and volunteer lawyers who together have served tens of thousands of people.

Now, at the helm of Equal Justice Works, my colleagues and I continue the longstanding work of building a movement of public interest leaders who are transforming the communities we live in, come from, and partner with. But we can’t do it alone.

These survey results remind us we have a long way to go. But we are in this for the long haul. Partnerships with law schools are a key part of our strategy. We support member law schools, the majority of accredited institutions in the nation, in myriad ways —from educating law school professionals through webinars and other informational resources or introducing thousands of students to the field in the nation’s largest public interest career fair, to preparing them for such careers through summer fellowships and our Public Interest Primer. In addition to those resources, our law school engagement and advocacy team travels the country, visiting member schools to meet with students and share information about our programs and opportunities. Through these efforts and more, Equal Justice Works seeks to fill in the gaps about public interest law for students. Thanks to the LSSSE survey, we have important information to help amplify our efforts.

When millions of people in the United States cannot access legal assistance to avoid eviction, maintain custody of their children, or escape an abusive partner, we need an all-hands-on deck solution. Every part of the legal profession must focus on this crisis. Law schools must continue to institutionalize their commitment to pro bono work and public service. By continuing to work together, we can empower this next generation of advocates to be ready to direct their passion for impact where it’s most necessary.