Deciding to go to Law School: Affording Undergraduates Insights on the Reality of Law School

Leena Hussain

Indiana University: Class of 2025

B.A. International Law and Institutions

Choosing to go to law school is a weighty decision for a number of reasons. There are financial concerns, concerns about success and interest, and ambiguity about the experience itself. As an undergraduate looking to go to law school, these worries weigh heavy on my mind. Like many, I often wonder what law school is like. What does lecture look like? How hard are classes and grading? How much reading is there really?

These contemplations require unique insights that may not come easily. Information for post graduate education can be hard to obtain if one does not know who to ask and where to look. How do we give undergraduates the opportunity to see, firsthand, the reality of law school? Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and the Maurer School of Law have partnered to grant pre-law students just this. In a class called Espionage and International Law, I sit with undergraduates and law students to study the legality of espionage globally. The class was created to provide a comprehensive experience with the rigor, cold calling, and grading that one often sees in law classes.

Undergraduates should be granted the opportunity to deeply explore the reality of law school. Getting these insights provide students the tools to prepare financially and mentally. Moreover, early insight will lead to more successful law students. The better prepared prospective students are, the better they will do in law school, resulting in stronger lawyers in the field.

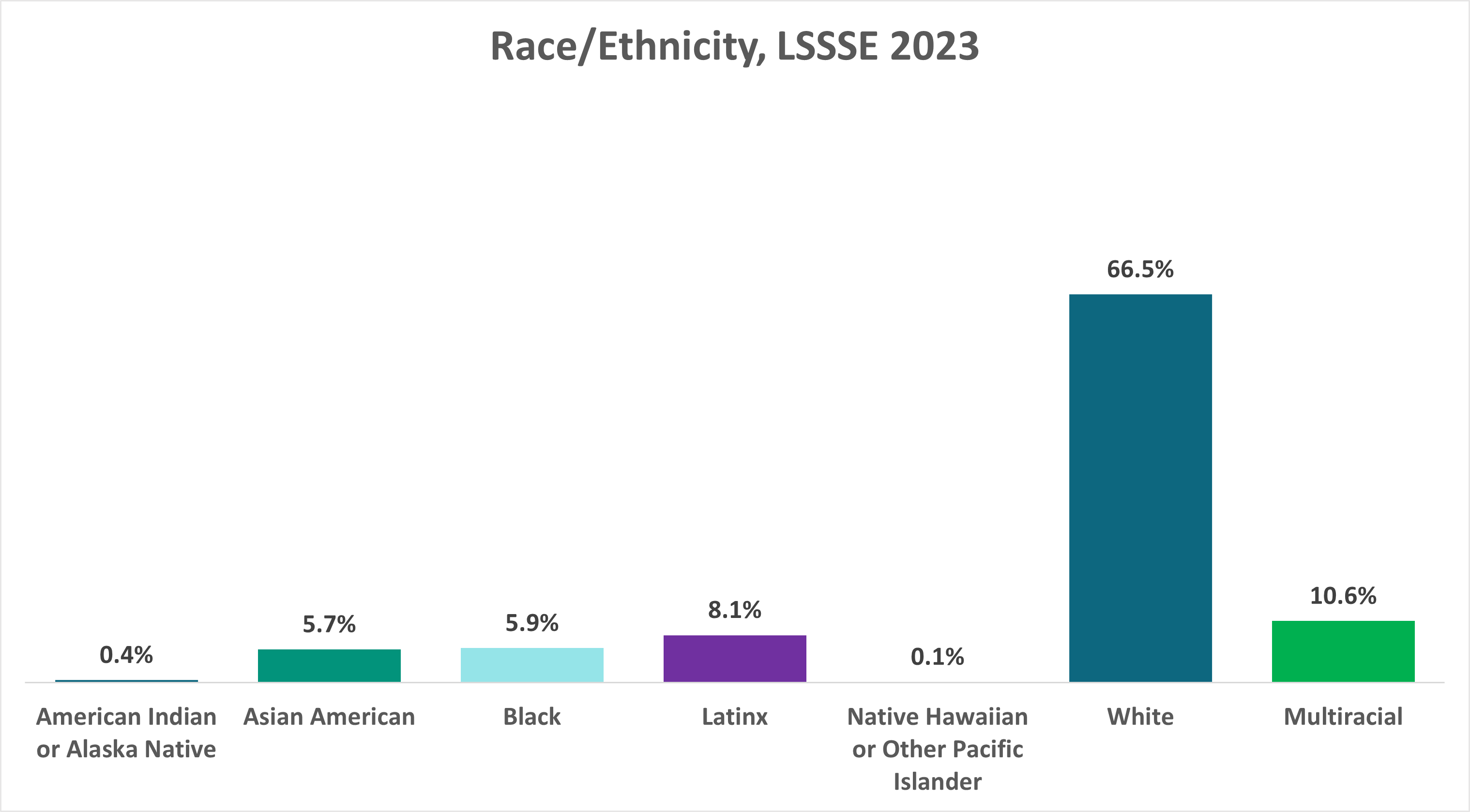

There may be large disparities in knowing where to look. The 2020 LSSSE report notes only a small increase in the demographic changes of minorities within law schools. Black, Asian, and Latinx groups saw their numbers go up only a few percent since 2004. While this is commendable growth, it can be better. Perhaps if these groups had more resources and insights on the law school experience, there would be more of these students in the field.

Classes like my espionage one are not the only way pre-law students can get exposure. Many law schools provide detailed overviews of what to expect in law classes. Penn State’s Pre-Law Advising website, for example, provides resources that detail lecture methods, the curriculum, exams, and grading. Undergraduates can also look for pre-law advisors or law professionals on their campuses for insights. These mentors can walk students through the admissions process as well as give advice for classes. Moreover, students can gain insights on the law through working at firms. JD Advising notes that working before going to law school familiarizes students to the legal world by giving them exposure to legal jargon, processes, and networks.

The groundwork exists, but there is still work to do in enabling all pre-law students to gain exposure to law school. Universities across the country can offer classes like my espionage class, develop stronger pre-law advising programs, and create comprehensive resources with insider information. While it is understandable to keep the field competitive, failing to address the hurdles that undergraduates may face in exploring law school is not. The decision to go law school is weighty, however, we can lighten the load by opening the experience.

How to Help Students with Procrastination

How to Help Students with Procrastination

Katie Rose Guest Pryal, JD, PhD

Parts of this essay are adapted from Katie Rose Guest Pryal, A LIGHT IN THE TOWER: A NEW RECKONING WITH MENTAL HEALTH IN HIGHER EDUCATION (U. Press of Kansas 2024)

There is a longstanding belief that procrastination is a manifestation of laziness, or just not caring about the work a person must do.

This belief is wrong.

As psychologist Devon Price, an expert on procrastination, has pointed out, “laziness does not exist.”[1] According to Price, procrastination is driven either by “anxiety about … not being ‘good enough’” or “by confusion about what the first steps of the task are.”

Contrary to popular belief, Price points out, “procrastination is more likely when the task is meaningful and the individual cares about doing it well.” In other words, when a person cares deeply about a task, the person can become paralyzed by the fear of failure.

Students will procrastinate; it is inevitable. We must learn what procrastination is and how it works so we can help our students.

What is procrastination?

According to psychologists, procrastination is “the voluntary delay of an intended act despite the awareness that this needless delay will be detrimental in the longer term.”[2]

Procrastination is thus something that the procrastinator is aware that they are doing, and that they are also aware will hurt them. Students (and faculty) who procrastinate are not lazy, or bad workers, or poor planners. They are struggling with a real psychological problem.

A recent study on procrastination found a link between feeling awful about yourself and procrastination. Procrastinators “have a chronic tendency to cognitively dwell on their dysphoric feelings [feelings of profound unhappiness] and on negative self-relevant information.”[3]

In other words, procrastinators chronically focus on their bad feelings about their lives in general and on bad feelings about themselves. Together, these bad feelings create chronic self-doubt, which leads to procrastination.

Researchers have found that “procrastination and depression were linked significantly.”[4] Indeed, these researchers found “the association between depression and procrastination-related thoughts was stronger” than they had expected it to be.

What Can We Do?

If a student of yours is struggling with procrastination, there is a strong chance that they are also struggling with depression or anxiety. If a student feels stressed or anxious about a task, they are more likely to procrastinate.

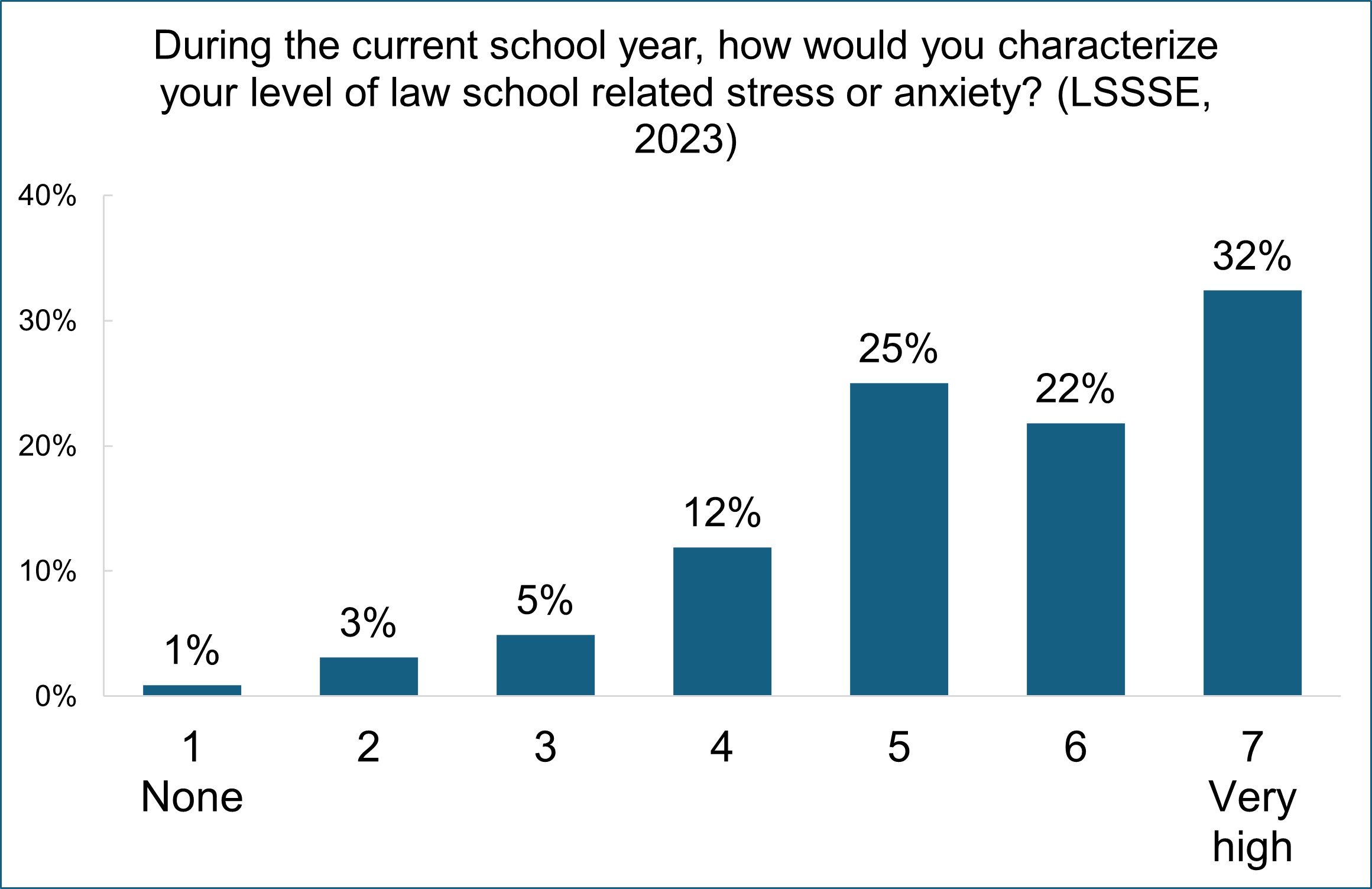

And many of our students do suffer from stress and anxiety during law school. Data from LSSSE reveal how widespread this problem is, with over half (54%) of respondents noting stress or anxiety at a level of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale:

You can think of procrastination as a cycle. Because of a stressful environment, a person’s mental health, awful life events, or all of the above, a person—we—feel poorly. Perhaps, because of these factors, we even develop depression or anxiety. Because we feel poorly, we cannot do our work. When we cannot do our work, we feel even worse, beginning the cycle again.

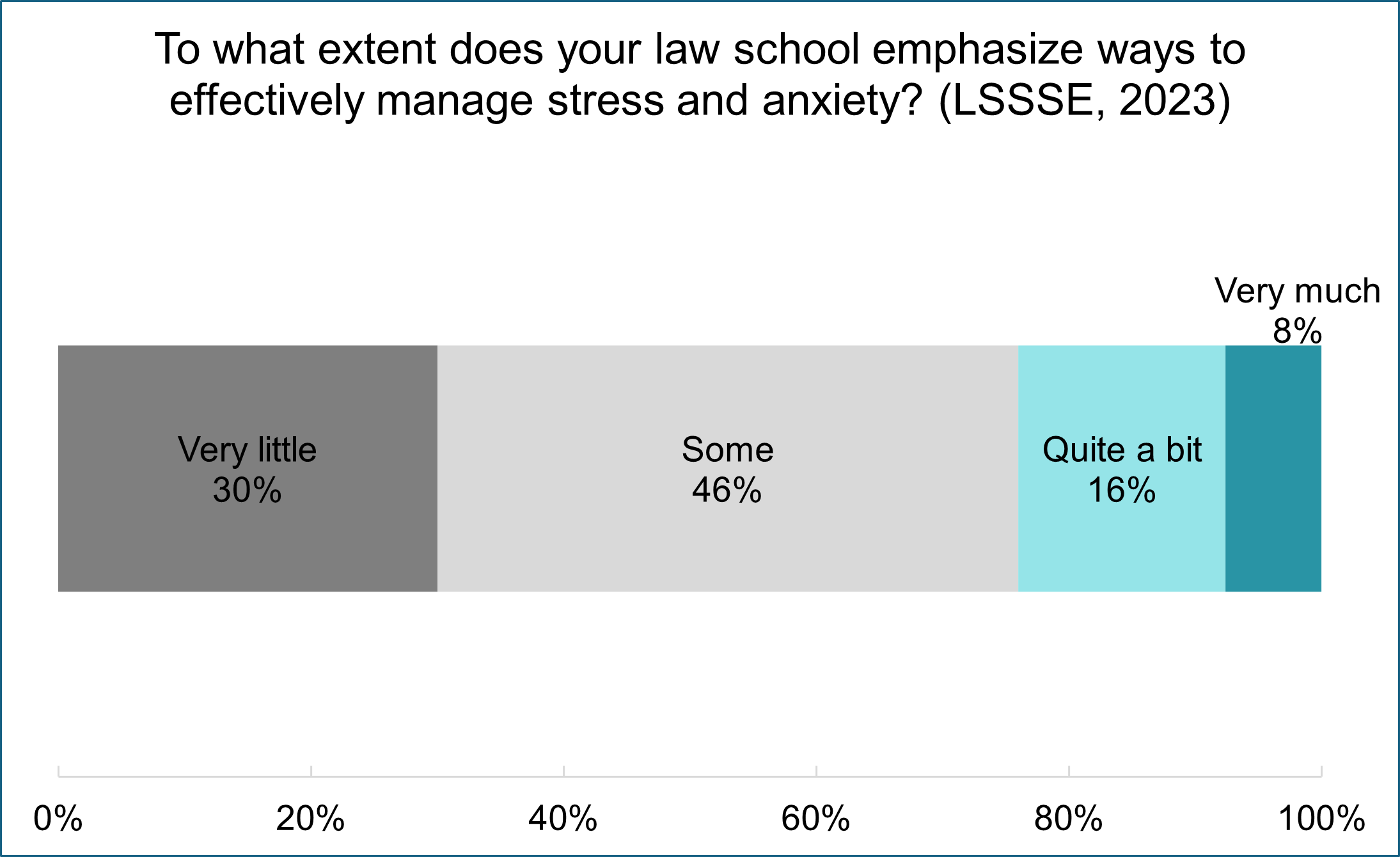

Institutions and faculty can intervene in this cycle. Yet we rarely do as much as we can to help. When asked whether their schools helps them manage stress and anxiety, a full 30% of LSSSE respondents say their schools do “very little” in this regard.

Instead, we can ask ourselves:

Instead, we can ask ourselves:

- Are we creating a needlessly stressful environment? If so, what can we do about it?

- Are we adequately tending to our students’ mental health? If not, how can we do so?

- Are we creating enough flexibility for students who are going through tough life events, such as the birth of a child or the death of a loved one? If not, how can we do so?

Remember, your students want to impress you. This desire starts on day one. Thus, they put pressure on themselves because the work is meaningful, as Price puts it, and if they procrastinate, it is for this same reason.

In the classroom

Try this teaching technique to lower the pressure on your students at the beginning of the semester. Assign a very low-stakes assignment the first week of class. Something small—a case brief in a lecture, or a one-half page reflection essay in a seminar. (You don’t have to grade them.)

Tell your students: “I want you to put in 70% effort on this. I do not want 100%, 90%, or 80%. If I see anything higher than 70%, then I will make you redo it to make it worse.” You will get laughs, and some bafflement. Give them till your next class to do it, and then collect them (on paper, via course software, it doesn’t matter).

You will find two things have occurred. First, usually all of your students will turn in the work because the 70% rule lowers the stakes and allows them to beat procrastination. You’ve told them that it is okay to turn in crap, which means it’s okay to be imperfect.

But the second thing you will find is that your students will turn in great work. You will get far fewer 70% assignments than you would expect. Without the pressure of perfect, students can achieve greatness.

You’ve set the tone for the rest of the semester: it’s okay to be imperfect. You just have to get it done. And great is pretty darn good.

___

[1] Devon Price, “Laziness Does Not Exist,” Human Parts, March 23, 2018, https://perma.cc/LZ8J-LXWU, https://humanparts.medium.com/laziness-does-not-exist-3af27e312d01. See also, Devon Price, Laziness Does Not Exist: A Defense of the Exhausted, Exploited, and Overworked (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021).

[2] Alison L. Flett, Mohsen Haghbin, and Timothy A. Pychyl, “Procrastination and Depression from a Cognitive Perspective: An Exploration of the Associations Among Procrastinatory Automatic Thoughts, Rumination, and Mindfulness,” The Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 34, no. 3 (September 2016): 170.

[3] Flett, Haghbin, and Pychyl, “Procrastination and Depression,” 180.

[4] Flett, Haghbin, and Pychyl, “Procrastination and Depression,” 182.

Guest Post - Black Faces in White Spaces: The Rise of the Black Law Review Editor in Chief

Gregory S. Parks

Professor of Law

Wake Forest University School of Law

Etienne C. Toussaint

Associate Professor of Law

University of South Carolina Joseph F. Rice School of Law

In the first seventy-three years of the Virginia Law Review’s existence, there were no Black members. In 1987, three Black students were welcomed as members of the Virginia Law Review, two of whom were invited because of a newly implemented affirmative action plan. Yet, it would take until 2021—approximately 108 years after the law journal’s establishment—for the Virginia Law Review to elect its first Black Editor-in-Chief (“EIC”), Tiffany Mickel. Some might argue that this narrative merely reflects the difficulty of joining, much less leading, one of the nation’s most prestigious law journals at one of its top-ranked law schools where the enrollment of Black students is routinely low. After all, Mickel is exceptional among Black law students nationwide as one of only a few Black women in the United States with a materials science and engineering degree from MIT. Yet, the Virginia Law Review’s story appears to be more of an illuminating trend concerning law review’s diversity problem than a heroic triumph for Black law students.

For example, in January 2022, Texas Law Review elected Jason Onyediri as its first Black EIC, after nearly 100 years of the journal’s existence, and Bradford McGann became Northwestern Law Review’s first Black EIC. More recently, in 2024, the Harvard Law Review elected law student Sophia Hunt as only its second Black woman president in 137 years. In fact, of the less than seventy Black EICs from the top 100 law schools across U.S. history, more than half were elected in the past ten years. What inspired the dramatic increase in the diversity of law review leadership in recent history, and why has it taken so long?

This question—what we call law review’s “diversity problem”—does not have an easy answer. While legal scholars have been talking about diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”) on law review boards for far longer than the past decade, no American law school has yet to solve it. Since at least the 1980s, scholars have studied the impact of affirmative action policies on the diversity of law review boards. Early studies revealed that law reviews that did not have an affirmative action program often had no non-White members at all, much less in positions of leadership on the editorial board. Further, these studies showed that law reviews that implemented a mixed-method editor selection process (e.g., assessing first-year grades alongside performance on a writing competition) only fared slightly better.

Few law reviews have implemented structural changes to both the editor selection and scholarship publication process. As a result, DEI on law reviews remains low. Further, even as law schools push for greater DEI in the classroom, few law schools seem to be concerned with the diversity of their law review boards.

Critics of affirmative action and progressive DEI efforts argue that law school’s so-called diversity problem does not imply that law schools are failing their law students or their local communities. Rather, they argue, too few qualified racially and ethnically minoritized students are applying to and enrolling in law school. Perhaps law review’s diversity problem is a symptom of law schools’ failure to admit more underrepresented students? Or, perhaps there is a lack of interest among Black students to join the law review and rise to leadership? We disagree. And the data support us.

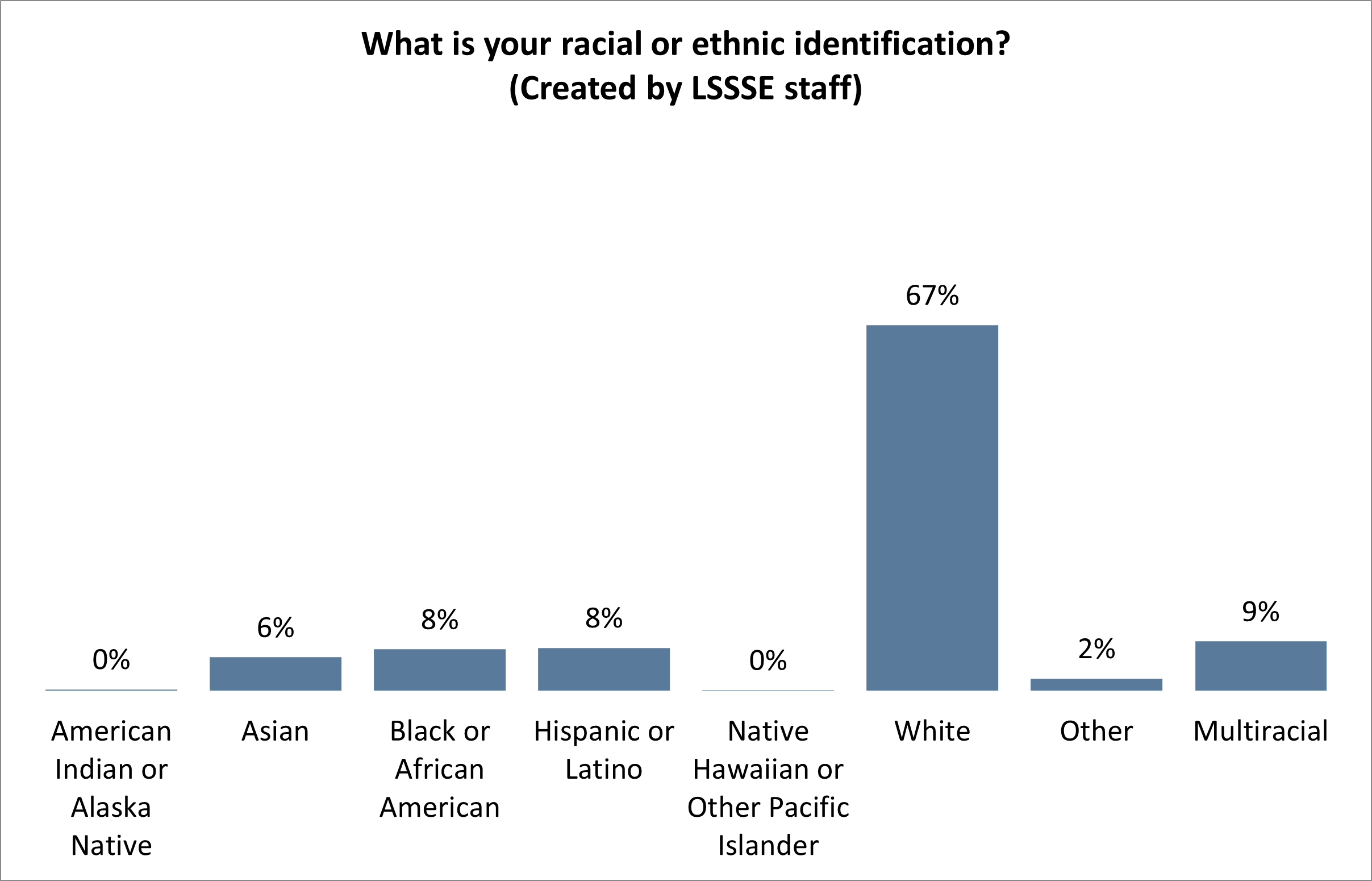

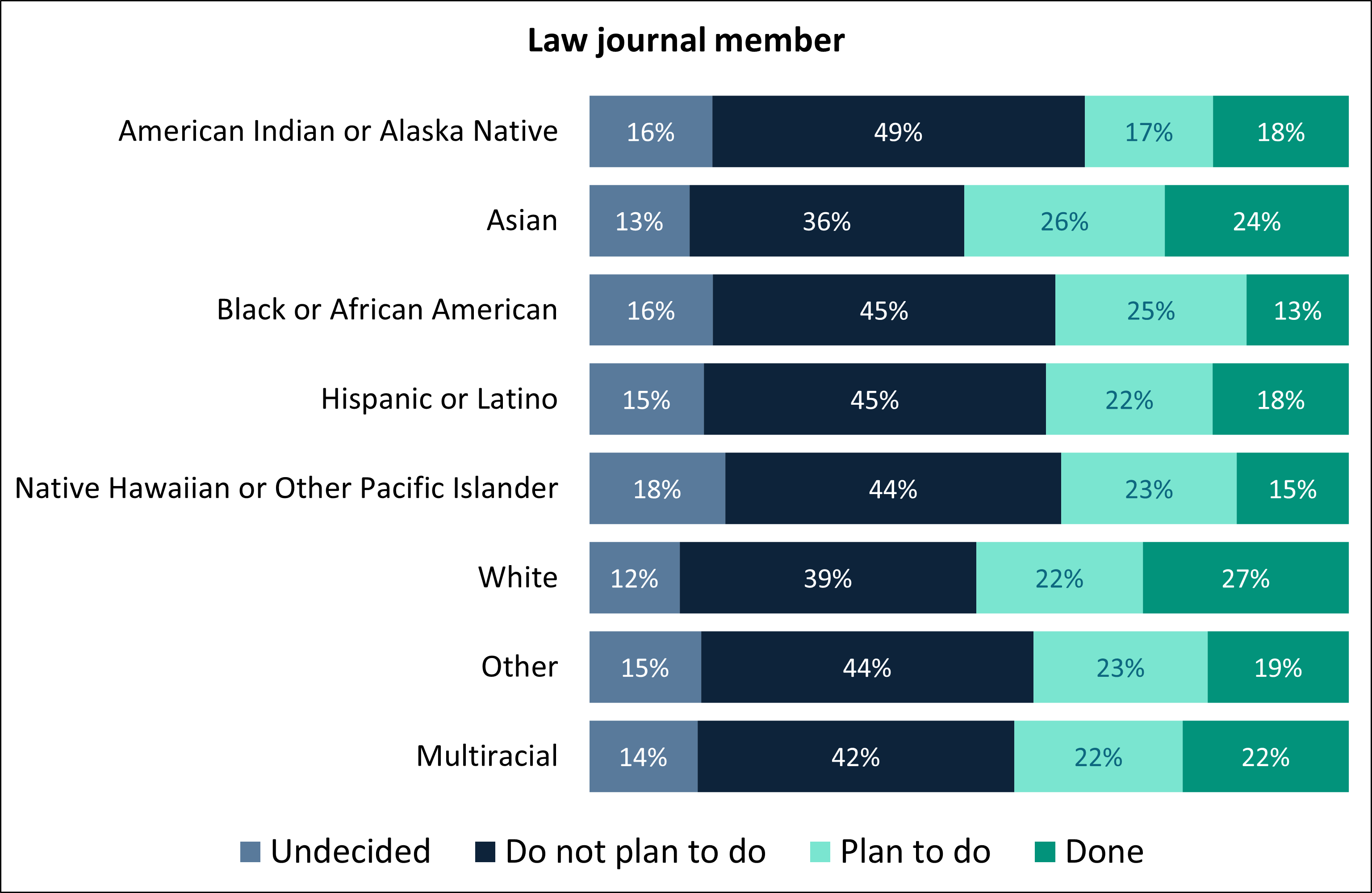

LSSSE data reveal that roughly 8% of current law students are Black. Still, while White students remain the majority (67%), many Black students continue to pursue opportunities to join and lead the law review. Furthermore, there is significant interest among Black students in joining other law journals. Approximately 13% of Black LSSSE respondents note that they have already joined a law journal and an additional 25% note that they plan to do so in the future. Accordingly, the (lack of) participation and leadership of Black law students on law reviews does not reflect apathy.

We believe that law review’s diversity problem must be engaged in the broader context of two complementary lenses: (1) sociopolitical efforts to eradicate racial injustice; and (2) institutional efforts to reform legal education.

On the one hand, the lens of socio-politics suggests that DEI efforts in law reviews experience the push and pull of racial attitudes and perceptions across the nation. For example, researchers have shown that although the election of President Barack Obama in 2008 improved the public’s perception of Black people’s work ethic and intelligence, racial attitudes became more polarized between 2009 and 2013, coinciding with an increased number of racially motivated killings of Black people nationwide. Nationwide calls for racial reckoning in the summer of 2020 after the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, among others, coincided with a dramatic uptick in Black EICs in 2021 and 2022. Accordingly, at least one driver of the increased attention to DEI issues in law reviews during the past ten years may be attributed to the increased attention nationwide to racial justice issues since President Obama’s election.

On the other hand, DEI efforts in law reviews also experience the push and pull of racial attitudes and perceptions across their law school community, including the views and attitudes of their faculty. Consider the current project of “building an Antiracist law school,” as Dean Danielle M. Conway of Penn State Dickinson Law puts it, that has been decades in the making. That effort has only been amplified in recent years, with law faculty increasingly prioritizing racial justice in their teaching and scholarship. Therefore, another driver of the increased attention to DEI issues in law reviews during the past ten years could be law professors’ increased attention to modern social movements, such as the Movement for Black Lives.

We argue that there are three fundamental drivers of law review’s diversity problem, with implications not just for law reviews, but for legal education writ large. First, there is confusion on the purpose of DEI. The purpose of DEI for law reviews is not solely to increase diversity on the law review roster to enhance the learning experience of students on the journal. A deeper purpose of DEI, we argue, is to realign the distorted function of the law review with its ideal purpose. While one of law review’s fundamental purposes is to promote scholarly discourse on law and law reform to promote the public’s interest, in practice, many law reviews serve merely as a gatekeeper for elite law practice and prestigious clerkships.

Second, there is confusion on the role that DEI plays in the legal education experience. The role of DEI for law reviews is not merely to increase the equality of opportunities for underrepresented students, nor simply to increase the discussion of marginalized experiences and diverse perspectives of law in public forums. We argue that the role of DEI is to articulate a more ambitious conception of “equity” in law, political economy, and legal education. As Lani Guinier argued, the very concept of meritocracy that governs how racially and ethnically minoritized students pursue equitable outcomes on the pathway toward legal practice must be challenged as an historically limited vision of legal education.

Finally, the value of DEI for law reviews has been distorted. The value of DEI is not simply its ability to increase the number of marginalized voices in mainstream legal discourse. DEI efforts must also challenge the culture of mainstream legal discourse altogether. Challenging elitism in the legal profession, we argue, requires a bold critique of the toxic ideologies that color societal views on meritocracy and leadership, which can influence the very color of law review itself.

To be sure, the recent wave of Black law review EICs is a bold step in the right direction. However, more work remains to dismantle the gatekeeping function of law reviews and transform it into an educational space open to all law students and all members of the broader community.

Guest Post - Digging Into Data: The Gems at the Back of the Bookstore

Digging Into Data: The Gems at the Back of the Bookstore

Digging Into Data: The Gems at the Back of the Bookstore

Tracy Turner

Associate Dean for Student Learning Outcomes

Graphs by Bradley Yost, Manager of Institutional Research

Southwestern Law School

For a student-focused school like my institution, Southwestern Law School, LSSSE survey results can sometimes be treated as an affirmation that we are doing a good job when our averages in desirable categories exceed the LSSSE average and the averages at our peer schools. And with the addition of an in-house institutional research expert, we have been able to start digging beneath the surface of the results by disaggregating data not only by demographics but also by cross-referencing answers to different questions within the survey. It feels like the difference between window shopping and burying our heads in the boxes stashed in the back of the bookstore where the real gems are hiding.

Sometimes the results merely confirmed suspicions. For example, student assessment of their relationships with faculty correlated with their experience in receiving prompt feedback on assignments and with their perception of support for their success. Other times, however, the results were surprising and raised interesting questions about how to support our students.

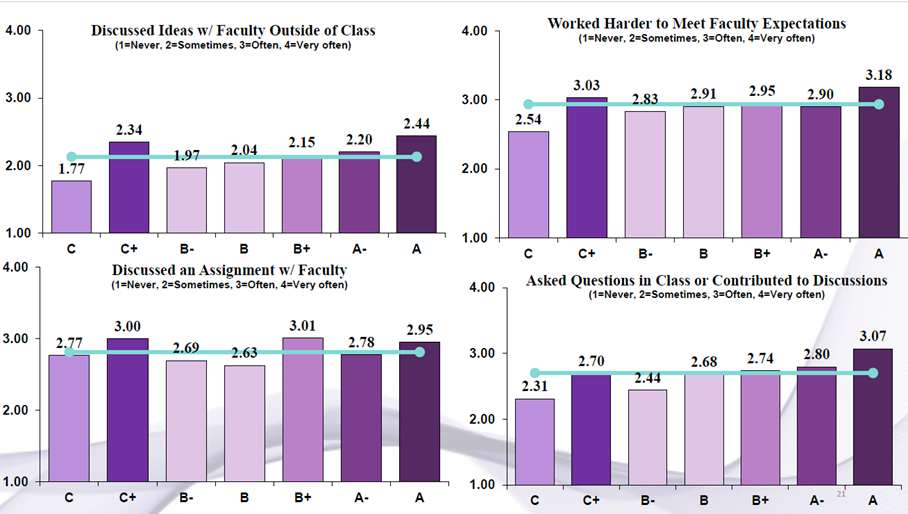

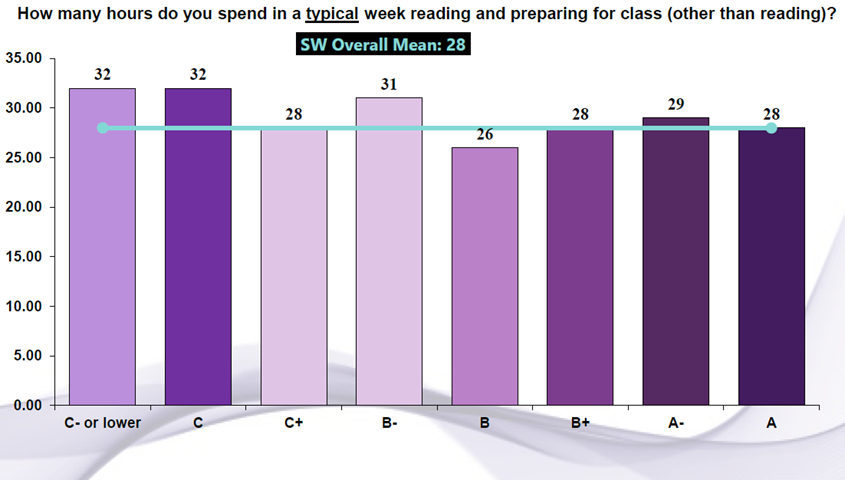

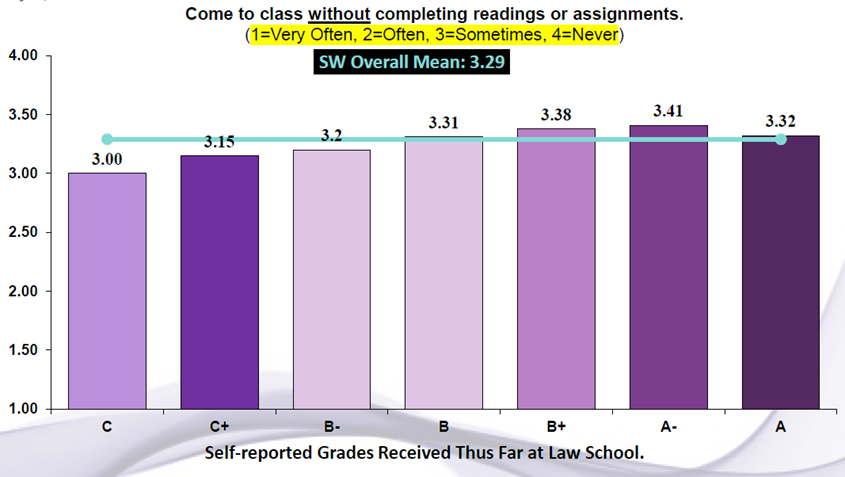

While we saw that GPA correlated fairly well with preparation, engagement, and self-perception of working hard, the correlation was not consistent: in each of these categories, our C+ students reported spending more time and working harder than the B students and in fact were very close to our A students. At C- and below, the correlation was strong.

What is happening with these C+ students that disrupts the correlation and is there something we can do to help them see some of the same payoff from effort that our higher-performing students experience?

What is happening with these C+ students that disrupts the correlation and is there something we can do to help them see some of the same payoff from effort that our higher-performing students experience?

Another important anomaly that surfaced was that students with lower GPAs reported spending more time reading than did B-level students and above, but at the same time reported that they failed to complete the reading more often.

Does this possibly suggest that less assigned reading might enable better performance in this category of students? Whatever the answer, the evidence that our lower-performing students are working hard but struggling to keep up with the reading is important information to consider in how we structure our required curriculum and individual course assignments.

Does this possibly suggest that less assigned reading might enable better performance in this category of students? Whatever the answer, the evidence that our lower-performing students are working hard but struggling to keep up with the reading is important information to consider in how we structure our required curriculum and individual course assignments.

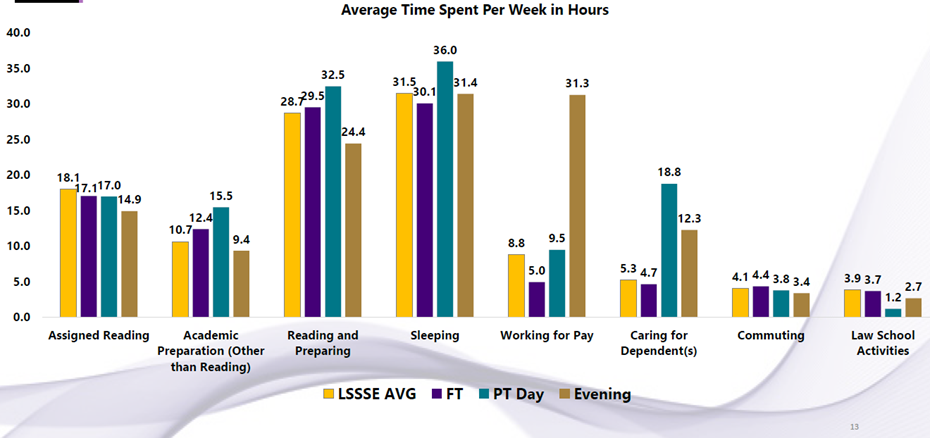

As one last example, we also compared the time that students reported spending on various school-related and personal tasks and learned that, on average, students spent more time commuting than engaging in extracurricular activities, and this result came years after building student housing on campus to address this very issue. And even our full-time students reported spending slightly more time on outside work than on extracurriculars.

This raises an important question about whether we could imagine interventions to decrease our students’ need to commute and find outside work. Next year, Southwestern will also be able to compare LSSSE responses and academic performance data from its in-residence program to data from its new fully online J.D. program ( https://www.swlaw.edu/Online).

This raises an important question about whether we could imagine interventions to decrease our students’ need to commute and find outside work. Next year, Southwestern will also be able to compare LSSSE responses and academic performance data from its in-residence program to data from its new fully online J.D. program ( https://www.swlaw.edu/Online).

We are only on round one with this level of disaggregation, and it will take one or two more repetitions before the information is truly actionable but the questions and thinking it has raised have already challenged some assumptions.

Another new way to use LSSSE that we have discovered is as part of our learning outcomes assessment process. Student answers regarding the extent to which they have been asked to synthesize and organize information and apply theories and concepts to new problems and situations serve as a useful indirect assessment tool for our learning outcomes on legal analysis. Although our initial experience with this was much like our prior experience with survey results – mostly confirming that we are doing well – we can next disaggregate these responses like we have with the other examples mentioned above to discover whether there are GPA correlations or class preparation or engagement correlations. We can thus examine whether student experience with these learning outcomes is consistent and which variables may have an impact.

These new approaches to LSSSE results are helping us use the survey as it was intended to be used – for discovery and improvement in our mission to maximize the success of our students.

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Erika K. Wilson

Professor of Law, Wade Edwards Distinguished Scholar, and Director of the Critical Race Lawyering Civil Rights Clinic

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 143 S. Ct. 2141 (2023) arguably ended race-conscious admissions policies as we know them. While the Court did not expressly overrule diversity as a compelling state interest, it did find that the way in which Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were using race to achieve diversity was unconstitutional. The majority opinion observed that universities undermined their stated interest in obtaining a racially diverse class by relying upon “opaque racial categories.” It identified as particularly problematic categorizing all Asian applicants together with no distinctions made between South and East Asians; the arbitrariness of the Hispanic categorization; and the under inclusiveness of the Middle Eastern classification. Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion made a similar observation with respect to the categorization of Black students:

The “Black or African American” category covers everyone from a descendant of enslaved persons who grew up poor in the rural south, to a first-generation child of wealthy Nigerian immigrants, to a Black-identifying applicant with multi-racial ancestry whose family lives in a typical American suburb.

Gorsuch’s critique is salient because the original purpose of race-conscious affirmative action programs was to remediate the multi-generational effects of slavery and the afterlives of slavery. Yet, as documented by legal scholars like Angela Onwuachi-Willig, in the early 2000s Black students at elite universities were overwhelmingly mixed-race students, or first- or second-generation Black Americans, meaning their parents and/or grandparents were immigrants. Lani Guinier and Henry Gates raised concerns in 2004 because only one-third of Harvard’s Black undergraduate students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America, descendants of persons enslaved in America.

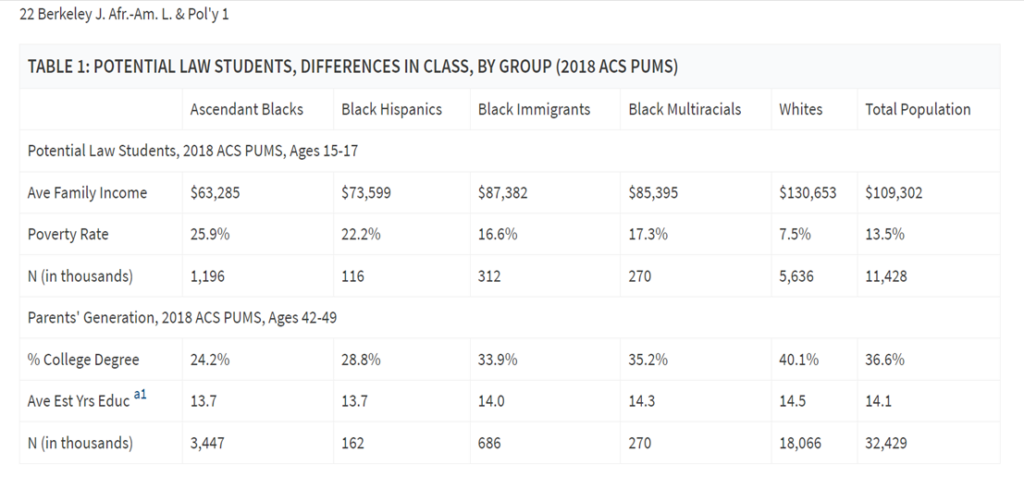

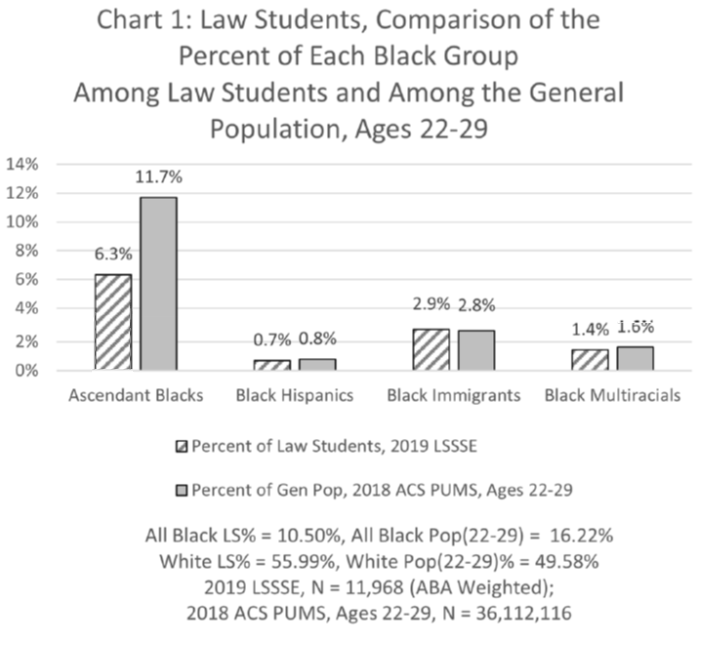

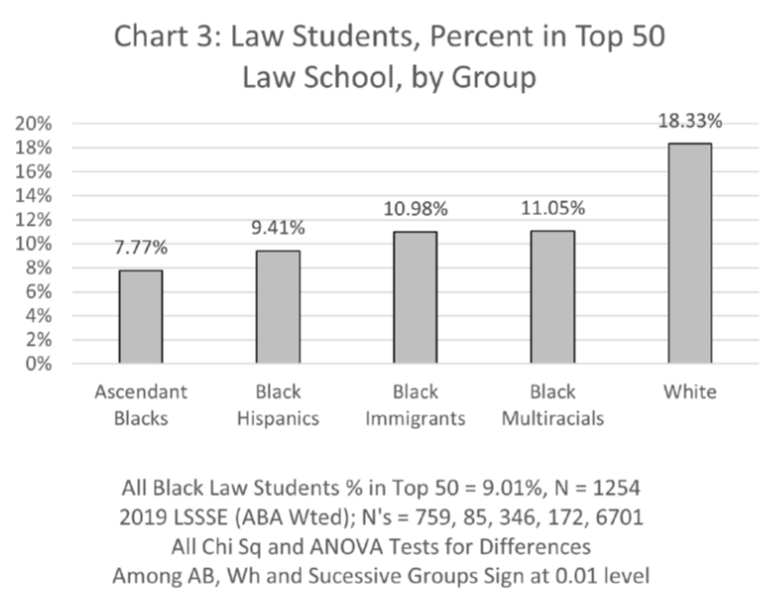

Recent research by Kevin Brown and Kenneth Dau-Schmidt relying on LSSSE Survey data shows that not much has changed since the early 2000s. Similar patterns of disproportionate representation of what Brown and Dau-Schmidt call “ascendant Blacks” (those with two American-born Black (non-biracial) parents) exists in law school enrollment today. The data show three noteworthy trends:

First, while structural racism impacts all Black people in America, it impacts some groups more acutely. As they write in their article, ascendant Black law students have lower average family incomes, higher poverty rates, and are less likely to have parents with a college degree.

Second, all Black people, except Black Immigrants (defined as Black people with at least one parent not born in America), are underrepresented among law students; furthermore, the extent of underrepresentation is much worse for ascendant Black law students than for other Black law students.

Third, ascendant Black law students are underrepresented at Top 50 law schools relative to their representation within the population of Black people in America, and relative to all other groups of Black law students.

The data and their implications should inform the path universities take to reinvent their affirmative action programs. Diversity is still recognized as a compelling state interest. Universities can and should fashion admissions programs that seek to increase representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. To be sure, they should also continue to make efforts to increase representation of all Black groups because race remains a salient and undeniable barrier for all Black people in America. Yet the unique burdens and history of subordination linked directly to American slavery imposes a special remedial obligation on universities to provide access to Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. This is especially true for elite universities such as Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that directly benefited from slavery.

In Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in Students for Fair Admissions, he offers a potential Constitutional path for doing so. He suggests that a classification consisting of descendants of persons enslaved in America is not a racial category. He contends that:

[The 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Act ] applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not [B]lacks writ large. And, because “not all [B]lacks in the United States were former slaves,” “ ‘freedman’ ” was a decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.

His comments, as other scholars have noted, raise questions as to the legality of an affirmative action program centered on descendants of persons formerly enslaved in America, as such a categorization may not be subject to the same level of heightened scrutiny as a race-based classification. Nonetheless, Thomas’ assertion that “freedmen” was not a racial categorization is admittedly dubious. But such a targeted program might also be justified under the remedial justification for race conscious policies. Thus, universities should take Thomas seriously. They should fashion admissions programs aimed at increasing the representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. LSSSE data and history demonstrate the normative case for doing so.