Aryssa Ham

Undergraduate Researcher

University of California, Davis

Public Service Intent Among Asian American Law Students

What drives people to set aside their personal interests to help the collective? In 2017, Yale Law School and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association found that Asian Americans gravitate towards careers in law firms and business over the public sector more than any other racial group, with few Asian Americans citing a desire to enter government as motivation to attend law school (Chung et al. 2017). Prior studies on the underrepresentation of racial minorities within the legal field often point to lack of academic or financial support as barriers to public service; yet Asian Americans were found to be the highest earning racial group in the U.S. and were overrepresented in top law schools (Sabharwal & Geva-May 2013; Kochhar & Cilluffo 2018; Chung et al. 2017).

This prompts a string of questions: Why are Asian Americans drawn to the private sector of the legal field? Why are they underrepresented in government and public interest? Alternatively, do Asian Americans prefer other forms of public service, such as pro bono work? If so, why doesn’t any other racial group appear to parallel this preference?

Despite past studies noting a weaker interest in the public sector among Asian Americans, few delve into potential explanations or examine variances among ethnicity. The original rallying, pan-ethnic Asian American identity has become a racial label that eclipses meaningful differences, propagating the Model Minority stereotype (Wu 2014:246). This social construct manifests in overlooked outcome disparities within the Asian American community, thus making ethnicity especially critical to examine.

As an undergraduate studying both psychology and sociology, I began an honors thesis last summer that integrates my majors: taking career decisions—a private, subjective experience—and zooming out to explore how these decisions interact with how society is organized and maintained. In my thesis, I study the professional trajectories of Asian Americans within the legal field—particularly the factors that determine whether and when an individual enters, stays, or switches into the public or private sector. Ultimately, I aim to shed light on why the legal profession is an underused entryway into government for Asian Americans, while simultaneously revealing the contrasting stories that vary by ethnicity.

Why LSSSE data?

I examine the extracurricular activities of law students to uncover patterns among students exhibiting public service motivation before fully entering the legal field. Although students can enter law school at different points in their life, I treat law school extracurriculars as the first major professional fork between the public and private sector.

While LSSSE data on student pro bono experiences are publicly accessible, ethnicity data are not shared on the website. After reaching out to Professor Meera Deo and LSSSE, they graciously provided the 2019 analyses that I needed.

I looked at 3 LSSSE Questions:

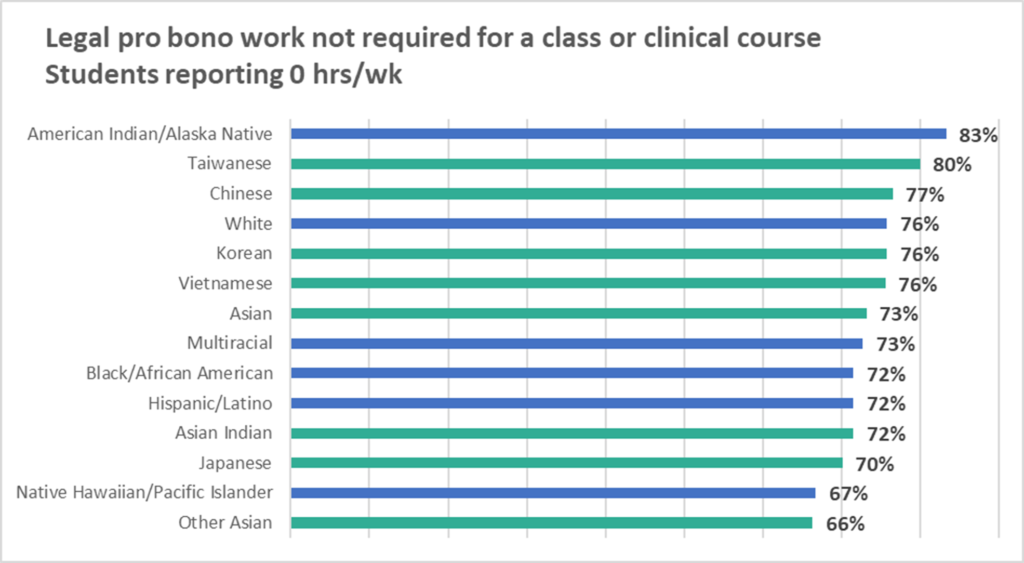

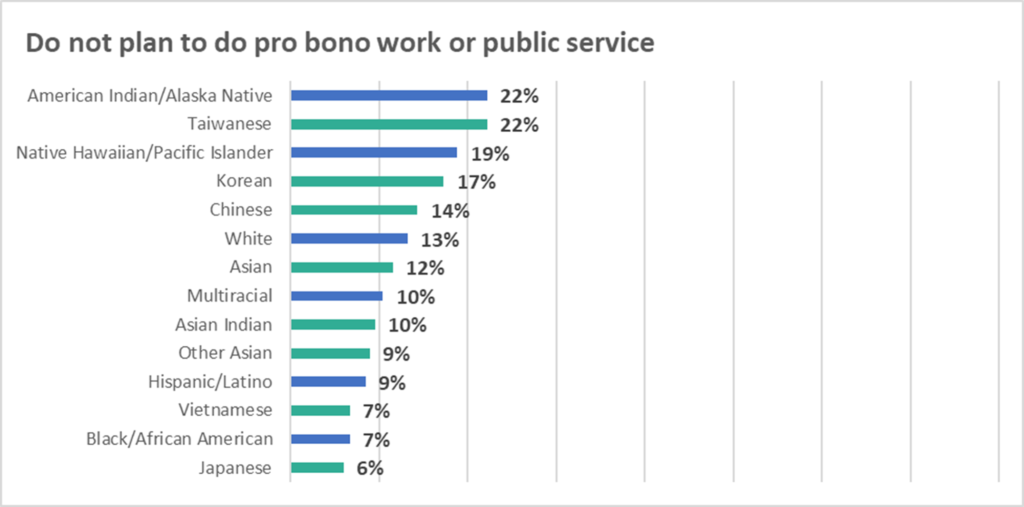

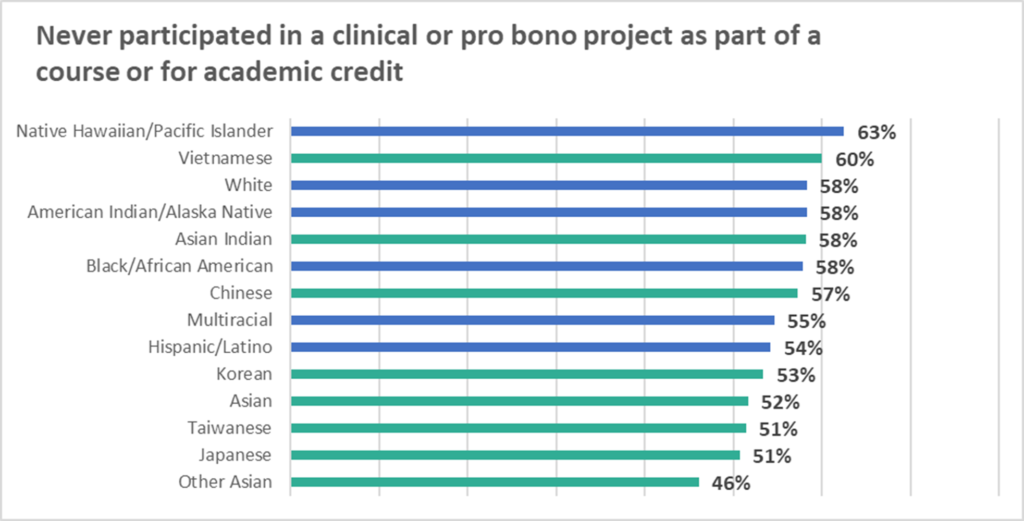

The first question (Pro Bono) asked for the number of hours a student spends each week doing legal pro bono work not required for a class or clinical course. The second (Public Service) asks if a student has done or plans to do pro bono work or public service before graduation, with response options “undecided,” “do not plan to do,” “plan to do,” or “done.” The final question (Clinical Project) asks how often a student has participated in a clinical or pro bono project as part of a course or for academic credit, with response options ranging from “never” to “very often.”

Here’s what I found:

Pro Bono: Asian ethnicities with greater proportions of participation in pro bono work tend to be those with higher than national median incomes and better representation as elected officials, with four Japanese Americans and five Asian Indian Americans currently holding office in U.S. Congress, while other Asian ethnicities, such as Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, or Vietnamese American, include one to two representatives, if at all. Other Asian, Japanese, and Asian Indian have the lowest proportion of students responding with “0 hours/week.”

Public Service: While this question tracks progress from 1L to 3L, the graph echoes the results of Pro Bono, with Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese American students being the only Asian ethnic groups with a higher proportion of “do not plan to do” than white students.

Clinical Project: The proportion of Asian Americans who have participated is the highest among all races. When broken down by ethnicity, Other Asian, Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean American have the lowest proportion of “never” responses. On the other end, proportions of Asian Indian Americans reporting “never” (58.2%) most closely mirrors those of white students (58.3%). Finally, Vietnamese Americans have the highest proportion aside from Hawaiian/Pacific Islander reporting “never,” but they also have the second-highest proportion reporting “very often,” only behind Other Asian.

Note: The “Other Asian” label is large, with a sample size more than doubling three of the six other reported Asian ethnicities. Ideally, a Filipino category would have been useful among the ethnic breakdowns, as Filipino Americans constitute the third largest proportion of Asian Americans.

Main Takeaway

The findings reiterate how the Model Minority stereotype harmfully obscures the needs of many Asian Americans. Although the proportion of Asian Americans who contribute pro bono work is lower than other racial minorities and higher than white students, Asian ethnicities with fewer structural constraints (e.g., higher national median income, greater government representation) contribute a greater proportion of pro bono hours than Black and Latinx students, leaving students of other Asian ethnicities potentially overlooked or under-supported.

This concludes the survey portion of my thesis. To complement the survey data, I am conducting interviews with Asian American lawyers in both the public and private sectors. I hope to code the transcripts for potential public service motivation factors, uncover individual attitudes toward the public sector, and fully explore the linear and nonlinear paths of Asian Americans in law.

Huge thanks to Professor Deo and the LSSSE staff for being incredibly helpful! As an undergrad, I was astonished at how willing they were to accommodate me, and I’m so grateful for their support.

Finally, if anything piqued your interest, please don’t hesitate to contact me at aham@ucdavis.edu.

References

Chung, Eric, Samuel Dong, Xiaonan April Hu, Christine Kwon and Goodwin Liu, Yale Law School & National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, A Portrait of Asian Americans in the Law (2017).

Kochhar, Rakesh, and Anthony Cilluffo. “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians.” Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 12 Jul. 2018, www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/.

Sabharwal, Meghna and Iris Geva-May, “Advancing Underrepresented Populations in the Public Sector: Approaches and Practices in the Instructional Pipeline.” Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19:4, 2013, 657-679, DOI: 10.1080/15236803.2013.12001758

“U.S. Asians Have a Wide Range of Income Levels.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 8 Sept. 2017, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/ft_17-09-08_asian_income/.