Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Christopher J. Robinette[1]

Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

In the fall of 2023, Southwestern Law School received ABA approval to operate the country’s first fully online Juris Doctor program. Moreover, to increase student flexibility, the program is asynchronous, with only a few voluntary synchronous sessions. In essence, the students and professor will not be online together in a Zoom room, but students will access videos of the professor and exercises on their own schedules.

As a law professor who has taught in-person courses for over twenty years, I deliberated a long time before volunteering to teach online. I love the energy of the face-to-face classroom and, frankly, I was somewhat skeptical about the efficacy of online law classes, particularly in the first year. In fact, one of the most compelling reasons that I agreed to teach online was the hope of improving my pedagogy in the “real” classroom. As I began planning my online course, however, I became excited about the possibilities particular to the online mode.

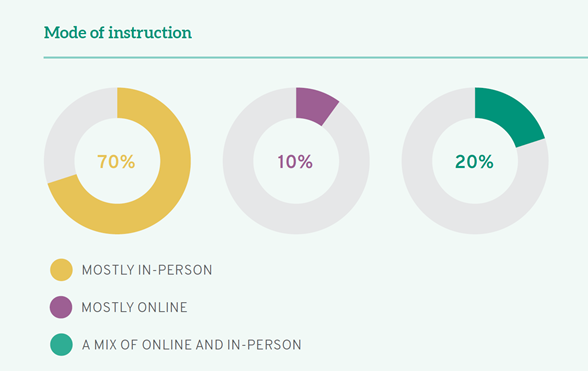

The 2022 LSSSE Annual Report, Success with Online Education, says half (50%) of all law students were enrolled in at least one course that was taught mostly or entirely online and every law school participating in the LSSSE survey offered at least some online courses. Most law students (70%) took courses that met in-person, though 10% took mostly online courses, and 20% reported that they had enrolled in a mix of courses that met online and in-person. Of those who did meet online, most (78%) were in synchronous classes; but 3% of LSSSE respondents in online courses met asynchronously and an additional 19% were in hybrid courses. Clearly, online education is here to stay and could grow even more prominent in the years ahead.

As an instructor, my biggest concern about teaching online was something about which LSSSE is expert: engagement. Keeping students engaged can be difficult under any circumstances, but it is especially challenging online. I believe a solution to the online engagement problem is not singular; instead, it lies in numerous program and instructional design decisions. With that in mind, I considered how law professors engage their students, particularly first years, in the traditional classroom. Of course, a major technique is the Socratic method, in which the professor asks a (usually cold-called) student increasingly challenging questions about a case. This is an interactive mode of teaching and learning that involves the students and does not conceive of them as passive recipients of knowledge. Although they exist, I do not need the overwhelming data telling me that active learning is superior. I can sense it in the fact that the air starts to go out of the room whenever I lecture my students for lengthy periods of time.

Was there a way to adapt the Socratic method to the online asynchronous environment? In thinking about this, I had to admit that one facet of the Socratic method in the classroom was not replicable. In the traditional classroom, the professor is able to tailor her follow-up questions precisely to the student’s answers. This is not possible in an asynchronous online class. But—and this is where I grasped that the online environment has advantages—you can ask all of the students all of the questions. In the traditional classroom, one student is on call. Ideally, we expect the other students to be following along and answering the questions silently for themselves. In reality, we know that at least some of them do not. They are spaced out, or shopping online, or simply exhausted. In an online course, all students can be engaged. And it can be verified.

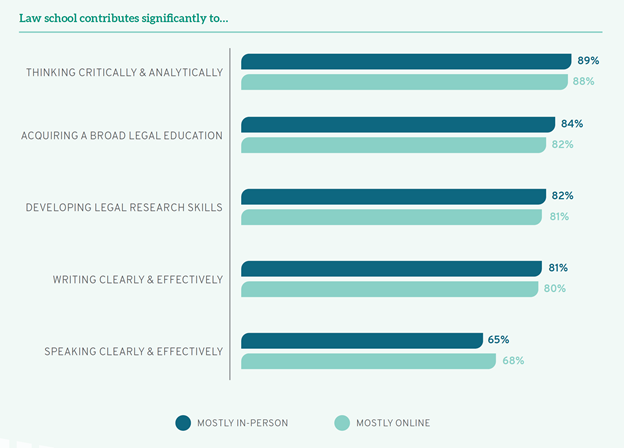

This is how I developed the Universal Socratic for my online course. For each module in my course, I selected one case that I found significant and created an interactive exercise around that case. I wrote five questions about the case. For the first few modules, I followed the structure of a basic case brief (facts, issue, holding, disposition, rationale), allowing the students to reinforce their briefing skills. As the modules progressed, I formulated more questions in the upper ranges of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analyzing, evaluating, and creating). Thanks to exercises like this, LSSSE data indicate that students believe legal education contributes to multiple skills, especially thinking critically and analytically, as much online as in-person.

I then drafted answers to the questions. Using Canvas’s Quizzes feature, I inserted the questions and required the students to answer them one at a time. After the student has answered each question, and before they answer the next question, they are shown my answer and are able to compare it to theirs. Not only asking the questions but providing prompt feedback is helpful to engage students. Using this process, the student and I are essentially having a dialogue, even though I do not have the benefit of their exact answer in real time in person. Moreover, every student in the class engages in the exercise of answering the questions.

Given the growth in online education, students will benefit from legal educators modifying effective face-to-face techniques, like the Socratic method, for the asynchronous online mode. When educators do so, they will find that some features of online education make it better than the original.

[1] I benefited greatly on this project from the ideas of my terrific colleagues Catherine Carpenter, John De Sousa, and Danni Hart.