Closing the Information Gap for Law Students Interested in Public Interest Careers

Verna L. Williams

CEO

Equal Justice Works

Our nation is experiencing an access to justice crisis. According to the Legal Service Corporation, 92% of low-income people’s civil legal needs went unmet in 2022, leaving a massive gap in our justice system. What’s more, the number of lawyers focusing on underserved populations is very small. According to the American Bar Association, fewer than one percent of lawyers are paid legal aid attorneys. As law schools plan for the coming academic year, I urge them to consider how to address this untenable gap in our legal system.

Put simply, creating lasting change for communities and in our justice system requires more graduates to choose public interest law. The fact that so few law graduates pursue this route is not only problematic, but also puzzling. As a law school dean, I saw first-hand that many aspiring attorneys chose legal education because they wanted to serve the public. In my new position as CEO of Equal Justice Works, a nonprofit that connects law students, law school professionals, lawyers, and advocates with fellowships at legal services organizations and other opportunities in public interest law, we are tackling this problem head on.

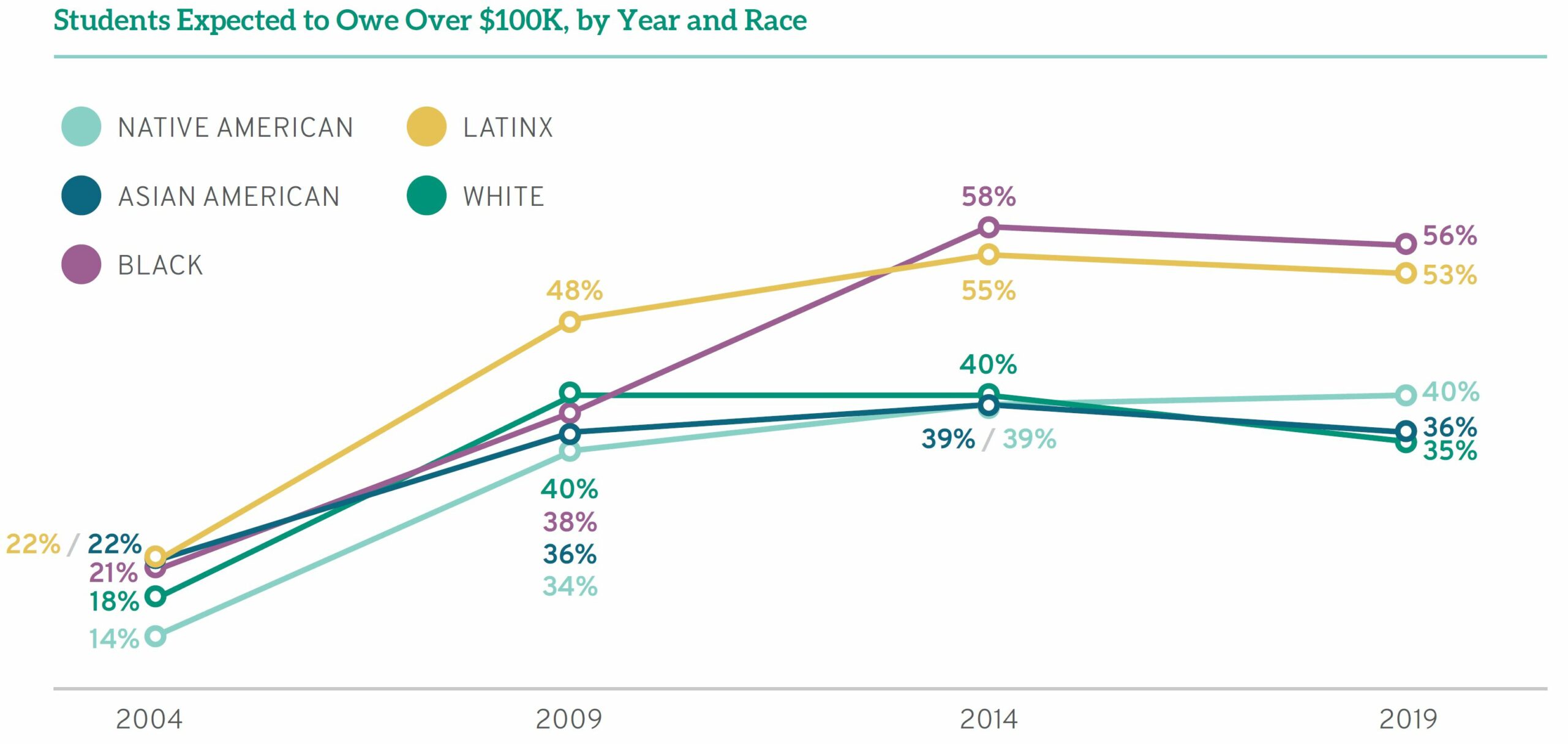

Consider student loan debt. AccessLex reports that, on average, law students borrowed $157,300 last year. Students of color graduate with an average educational debt twice the amount of their white classmates. With entry-level public interest attorneys earning a median $63,200, compared to $200,000 for law firm associates, it’s hardly surprising that so many graduates would choose private practice.

What else explains the dearth of public interest attorneys? To answer that question, Equal Justice Works partnered with the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), an invaluable resource, to identify blind spots in supporting future public interest lawyers. Working with LSSSE, we crafted questions for the 2023 LSSSE Survey to help quantify just how accessible information about pursuing public interest law is for law students across surveyed law schools.

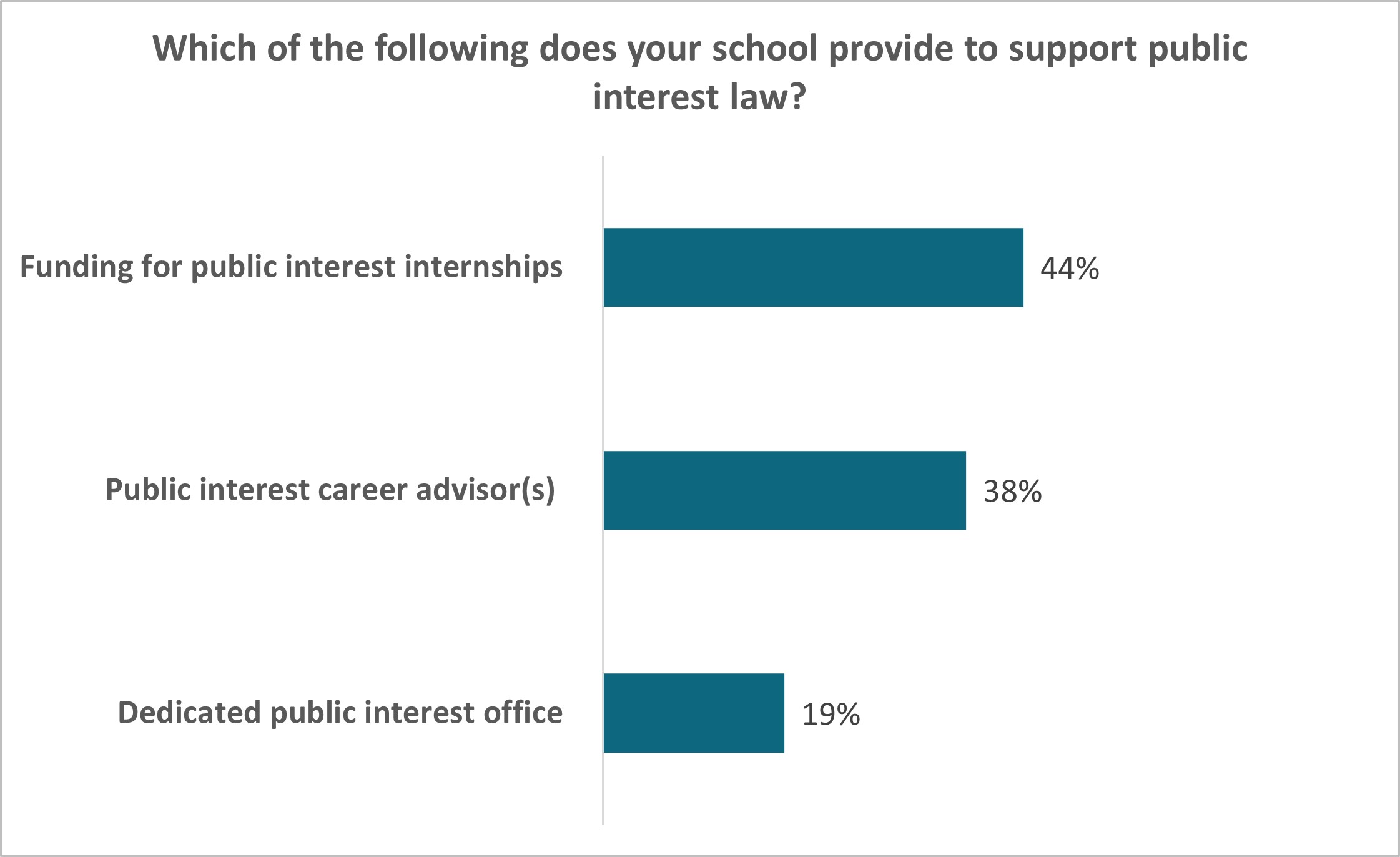

The results illustrate that many opportunities exist for legal education to build or strengthen support for new public interest lawyers. Among the findings:

- Only 44% of participating schools provide funding for public interest internships.

- An even smaller percentage of schools, 38%, employ public interest career advisors.

- Just 19% of law schools have a dedicated public interest office.

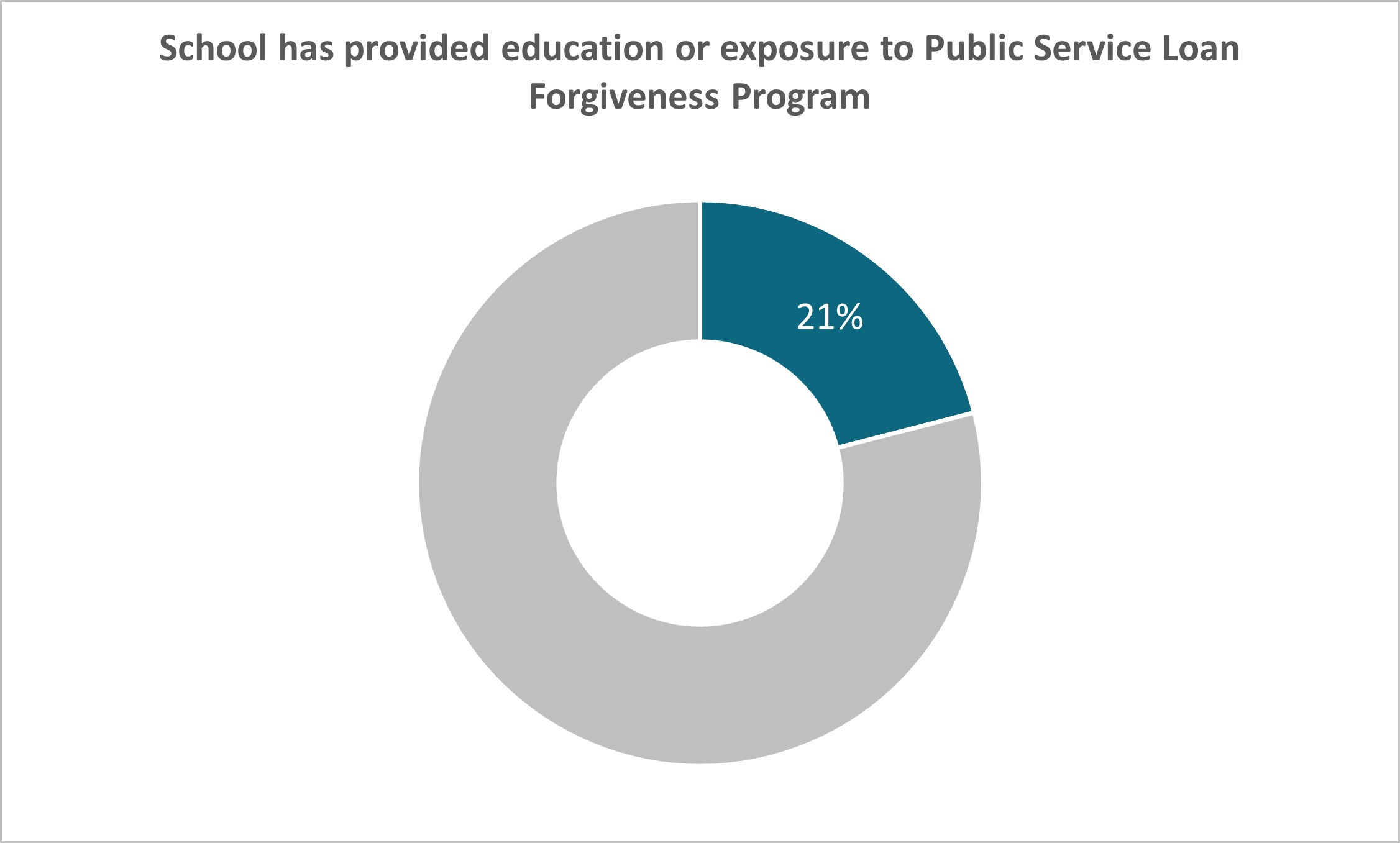

- When asked whether their school provided education and exposure to tools like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), the answer was a disheartening 21% responded in the affirmative.

The result is a knowledge gap about how to make the most of existing resources that can make pursuing public interest feel less like fantasy and more of a reality.

The LSSSE survey results strike a chord in me. Like today’s students, I chose law school because I wanted to make a difference. But before I began my public interest journey, I practiced in BigLaw to get my financial house in order—when I graduated, loan repayment assistance plans were brand new. I was able to get settled with my associate’s salary, paid off some debt, and never looked back.

My debt was considerably less than that of today’s student – but no less frightening. I wouldn’t trade my trajectory for anything, having had the privilege of practicing at the Department of Justice and the National Women’s Law Center. I built on those experiences as a faculty member at the University of Cincinnati College of Law (UC), in part, to create and support the next generation of feminist legal advocates. As a faculty member, I co-founded and co-directed the Nathaniel Jones Center for Race, Gender, and Social Justice, through which we created a clinic, advised students seeking public interest fellowships, and put on programs about how to “make a difference while making a buck.” Serving as dean of the law school allowed me to facilitate other efforts to make public interest opportunities available to students. I’m especially proud of the partnership we engaged in with Hamilton County Municipal Court to create the Help Center, which provided assistance to unrepresented litigants. Staffed by a UC attorney, the Help Center engaged students and volunteer lawyers who together have served tens of thousands of people.

Now, at the helm of Equal Justice Works, my colleagues and I continue the longstanding work of building a movement of public interest leaders who are transforming the communities we live in, come from, and partner with. But we can’t do it alone.

These survey results remind us we have a long way to go. But we are in this for the long haul. Partnerships with law schools are a key part of our strategy. We support member law schools, the majority of accredited institutions in the nation, in myriad ways —from educating law school professionals through webinars and other informational resources or introducing thousands of students to the field in the nation’s largest public interest career fair, to preparing them for such careers through summer fellowships and our Public Interest Primer. In addition to those resources, our law school engagement and advocacy team travels the country, visiting member schools to meet with students and share information about our programs and opportunities. Through these efforts and more, Equal Justice Works seeks to fill in the gaps about public interest law for students. Thanks to the LSSSE survey, we have important information to help amplify our efforts.

When millions of people in the United States cannot access legal assistance to avoid eviction, maintain custody of their children, or escape an abusive partner, we need an all-hands-on deck solution. Every part of the legal profession must focus on this crisis. Law schools must continue to institutionalize their commitment to pro bono work and public service. By continuing to work together, we can empower this next generation of advocates to be ready to direct their passion for impact where it’s most necessary.

Deciding to go to Law School: Affording Undergraduates Insights on the Reality of Law School

Leena Hussain

Indiana University: Class of 2025

B.A. International Law and Institutions

Choosing to go to law school is a weighty decision for a number of reasons. There are financial concerns, concerns about success and interest, and ambiguity about the experience itself. As an undergraduate looking to go to law school, these worries weigh heavy on my mind. Like many, I often wonder what law school is like. What does lecture look like? How hard are classes and grading? How much reading is there really?

These contemplations require unique insights that may not come easily. Information for post graduate education can be hard to obtain if one does not know who to ask and where to look. How do we give undergraduates the opportunity to see, firsthand, the reality of law school? Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and the Maurer School of Law have partnered to grant pre-law students just this. In a class called Espionage and International Law, I sit with undergraduates and law students to study the legality of espionage globally. The class was created to provide a comprehensive experience with the rigor, cold calling, and grading that one often sees in law classes.

Undergraduates should be granted the opportunity to deeply explore the reality of law school. Getting these insights provide students the tools to prepare financially and mentally. Moreover, early insight will lead to more successful law students. The better prepared prospective students are, the better they will do in law school, resulting in stronger lawyers in the field.

There may be large disparities in knowing where to look. The 2020 LSSSE report notes only a small increase in the demographic changes of minorities within law schools. Black, Asian, and Latinx groups saw their numbers go up only a few percent since 2004. While this is commendable growth, it can be better. Perhaps if these groups had more resources and insights on the law school experience, there would be more of these students in the field.

Classes like my espionage one are not the only way pre-law students can get exposure. Many law schools provide detailed overviews of what to expect in law classes. Penn State’s Pre-Law Advising website, for example, provides resources that detail lecture methods, the curriculum, exams, and grading. Undergraduates can also look for pre-law advisors or law professionals on their campuses for insights. These mentors can walk students through the admissions process as well as give advice for classes. Moreover, students can gain insights on the law through working at firms. JD Advising notes that working before going to law school familiarizes students to the legal world by giving them exposure to legal jargon, processes, and networks.

The groundwork exists, but there is still work to do in enabling all pre-law students to gain exposure to law school. Universities across the country can offer classes like my espionage class, develop stronger pre-law advising programs, and create comprehensive resources with insider information. While it is understandable to keep the field competitive, failing to address the hurdles that undergraduates may face in exploring law school is not. The decision to go law school is weighty, however, we can lighten the load by opening the experience.

How to Help Students with Procrastination

How to Help Students with Procrastination

Katie Rose Guest Pryal, JD, PhD

Parts of this essay are adapted from Katie Rose Guest Pryal, A LIGHT IN THE TOWER: A NEW RECKONING WITH MENTAL HEALTH IN HIGHER EDUCATION (U. Press of Kansas 2024)

There is a longstanding belief that procrastination is a manifestation of laziness, or just not caring about the work a person must do.

This belief is wrong.

As psychologist Devon Price, an expert on procrastination, has pointed out, “laziness does not exist.”[1] According to Price, procrastination is driven either by “anxiety about … not being ‘good enough’” or “by confusion about what the first steps of the task are.”

Contrary to popular belief, Price points out, “procrastination is more likely when the task is meaningful and the individual cares about doing it well.” In other words, when a person cares deeply about a task, the person can become paralyzed by the fear of failure.

Students will procrastinate; it is inevitable. We must learn what procrastination is and how it works so we can help our students.

What is procrastination?

According to psychologists, procrastination is “the voluntary delay of an intended act despite the awareness that this needless delay will be detrimental in the longer term.”[2]

Procrastination is thus something that the procrastinator is aware that they are doing, and that they are also aware will hurt them. Students (and faculty) who procrastinate are not lazy, or bad workers, or poor planners. They are struggling with a real psychological problem.

A recent study on procrastination found a link between feeling awful about yourself and procrastination. Procrastinators “have a chronic tendency to cognitively dwell on their dysphoric feelings [feelings of profound unhappiness] and on negative self-relevant information.”[3]

In other words, procrastinators chronically focus on their bad feelings about their lives in general and on bad feelings about themselves. Together, these bad feelings create chronic self-doubt, which leads to procrastination.

Researchers have found that “procrastination and depression were linked significantly.”[4] Indeed, these researchers found “the association between depression and procrastination-related thoughts was stronger” than they had expected it to be.

What Can We Do?

If a student of yours is struggling with procrastination, there is a strong chance that they are also struggling with depression or anxiety. If a student feels stressed or anxious about a task, they are more likely to procrastinate.

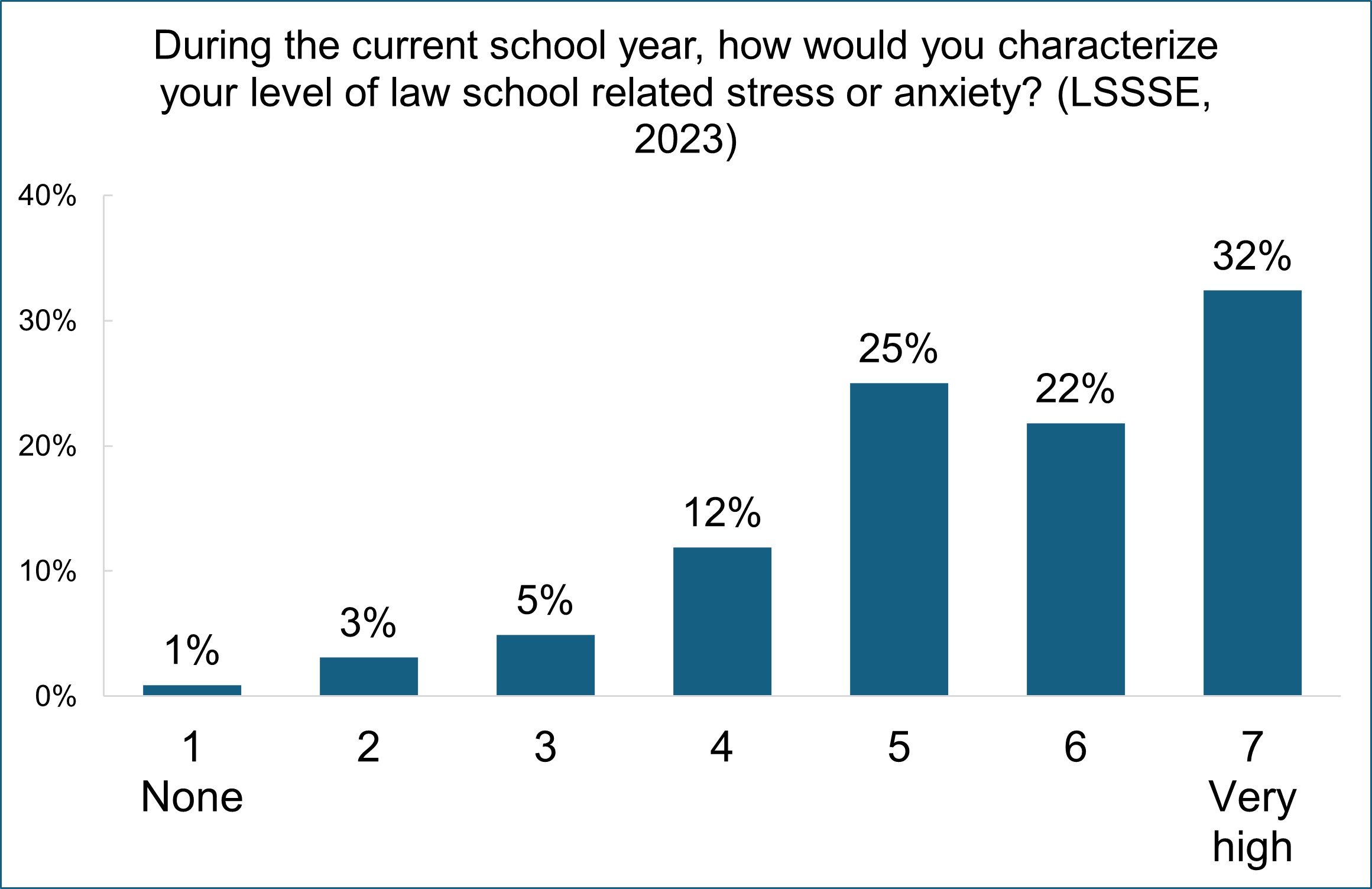

And many of our students do suffer from stress and anxiety during law school. Data from LSSSE reveal how widespread this problem is, with over half (54%) of respondents noting stress or anxiety at a level of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale:

You can think of procrastination as a cycle. Because of a stressful environment, a person’s mental health, awful life events, or all of the above, a person—we—feel poorly. Perhaps, because of these factors, we even develop depression or anxiety. Because we feel poorly, we cannot do our work. When we cannot do our work, we feel even worse, beginning the cycle again.

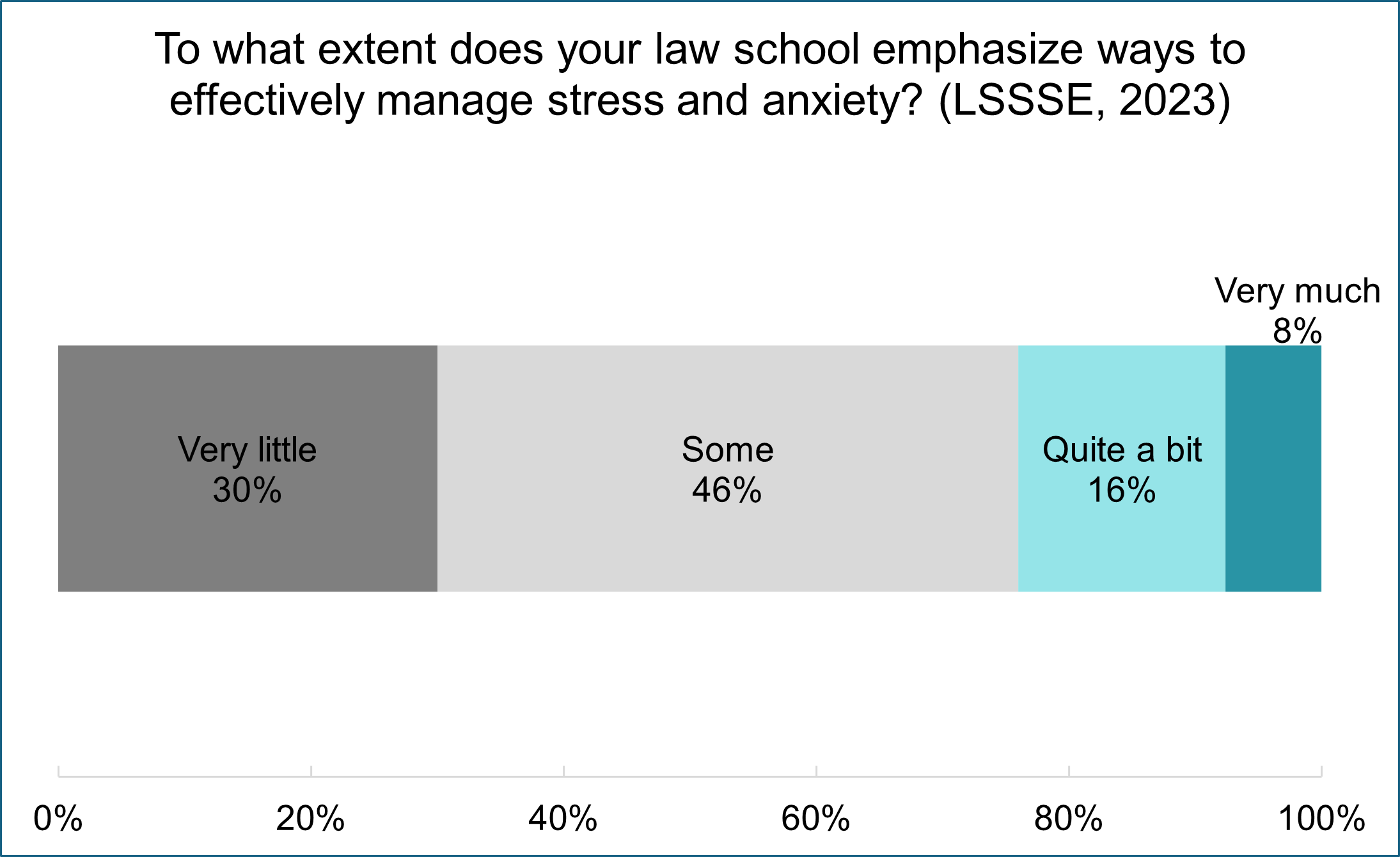

Institutions and faculty can intervene in this cycle. Yet we rarely do as much as we can to help. When asked whether their schools helps them manage stress and anxiety, a full 30% of LSSSE respondents say their schools do “very little” in this regard.

Instead, we can ask ourselves:

Instead, we can ask ourselves:

- Are we creating a needlessly stressful environment? If so, what can we do about it?

- Are we adequately tending to our students’ mental health? If not, how can we do so?

- Are we creating enough flexibility for students who are going through tough life events, such as the birth of a child or the death of a loved one? If not, how can we do so?

Remember, your students want to impress you. This desire starts on day one. Thus, they put pressure on themselves because the work is meaningful, as Price puts it, and if they procrastinate, it is for this same reason.

In the classroom

Try this teaching technique to lower the pressure on your students at the beginning of the semester. Assign a very low-stakes assignment the first week of class. Something small—a case brief in a lecture, or a one-half page reflection essay in a seminar. (You don’t have to grade them.)

Tell your students: “I want you to put in 70% effort on this. I do not want 100%, 90%, or 80%. If I see anything higher than 70%, then I will make you redo it to make it worse.” You will get laughs, and some bafflement. Give them till your next class to do it, and then collect them (on paper, via course software, it doesn’t matter).

You will find two things have occurred. First, usually all of your students will turn in the work because the 70% rule lowers the stakes and allows them to beat procrastination. You’ve told them that it is okay to turn in crap, which means it’s okay to be imperfect.

But the second thing you will find is that your students will turn in great work. You will get far fewer 70% assignments than you would expect. Without the pressure of perfect, students can achieve greatness.

You’ve set the tone for the rest of the semester: it’s okay to be imperfect. You just have to get it done. And great is pretty darn good.

___

[1] Devon Price, “Laziness Does Not Exist,” Human Parts, March 23, 2018, https://perma.cc/LZ8J-LXWU, https://humanparts.medium.com/laziness-does-not-exist-3af27e312d01. See also, Devon Price, Laziness Does Not Exist: A Defense of the Exhausted, Exploited, and Overworked (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021).

[2] Alison L. Flett, Mohsen Haghbin, and Timothy A. Pychyl, “Procrastination and Depression from a Cognitive Perspective: An Exploration of the Associations Among Procrastinatory Automatic Thoughts, Rumination, and Mindfulness,” The Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 34, no. 3 (September 2016): 170.

[3] Flett, Haghbin, and Pychyl, “Procrastination and Depression,” 180.

[4] Flett, Haghbin, and Pychyl, “Procrastination and Depression,” 182.

Guest Post - Black Faces in White Spaces: The Rise of the Black Law Review Editor in Chief

Gregory S. Parks

Professor of Law

Wake Forest University School of Law

Etienne C. Toussaint

Associate Professor of Law

University of South Carolina Joseph F. Rice School of Law

In the first seventy-three years of the Virginia Law Review’s existence, there were no Black members. In 1987, three Black students were welcomed as members of the Virginia Law Review, two of whom were invited because of a newly implemented affirmative action plan. Yet, it would take until 2021—approximately 108 years after the law journal’s establishment—for the Virginia Law Review to elect its first Black Editor-in-Chief (“EIC”), Tiffany Mickel. Some might argue that this narrative merely reflects the difficulty of joining, much less leading, one of the nation’s most prestigious law journals at one of its top-ranked law schools where the enrollment of Black students is routinely low. After all, Mickel is exceptional among Black law students nationwide as one of only a few Black women in the United States with a materials science and engineering degree from MIT. Yet, the Virginia Law Review’s story appears to be more of an illuminating trend concerning law review’s diversity problem than a heroic triumph for Black law students.

For example, in January 2022, Texas Law Review elected Jason Onyediri as its first Black EIC, after nearly 100 years of the journal’s existence, and Bradford McGann became Northwestern Law Review’s first Black EIC. More recently, in 2024, the Harvard Law Review elected law student Sophia Hunt as only its second Black woman president in 137 years. In fact, of the less than seventy Black EICs from the top 100 law schools across U.S. history, more than half were elected in the past ten years. What inspired the dramatic increase in the diversity of law review leadership in recent history, and why has it taken so long?

This question—what we call law review’s “diversity problem”—does not have an easy answer. While legal scholars have been talking about diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”) on law review boards for far longer than the past decade, no American law school has yet to solve it. Since at least the 1980s, scholars have studied the impact of affirmative action policies on the diversity of law review boards. Early studies revealed that law reviews that did not have an affirmative action program often had no non-White members at all, much less in positions of leadership on the editorial board. Further, these studies showed that law reviews that implemented a mixed-method editor selection process (e.g., assessing first-year grades alongside performance on a writing competition) only fared slightly better.

Few law reviews have implemented structural changes to both the editor selection and scholarship publication process. As a result, DEI on law reviews remains low. Further, even as law schools push for greater DEI in the classroom, few law schools seem to be concerned with the diversity of their law review boards.

Critics of affirmative action and progressive DEI efforts argue that law school’s so-called diversity problem does not imply that law schools are failing their law students or their local communities. Rather, they argue, too few qualified racially and ethnically minoritized students are applying to and enrolling in law school. Perhaps law review’s diversity problem is a symptom of law schools’ failure to admit more underrepresented students? Or, perhaps there is a lack of interest among Black students to join the law review and rise to leadership? We disagree. And the data support us.

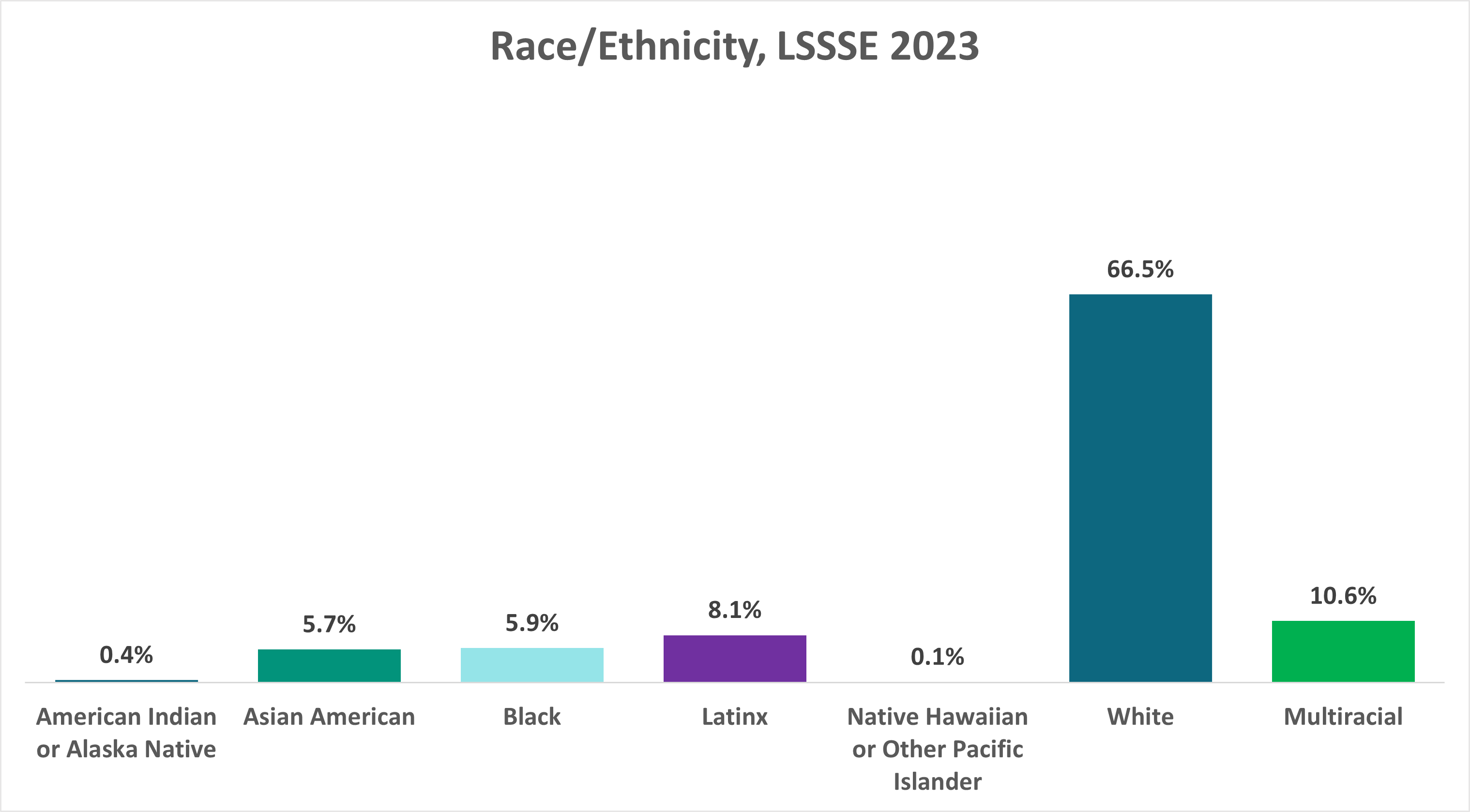

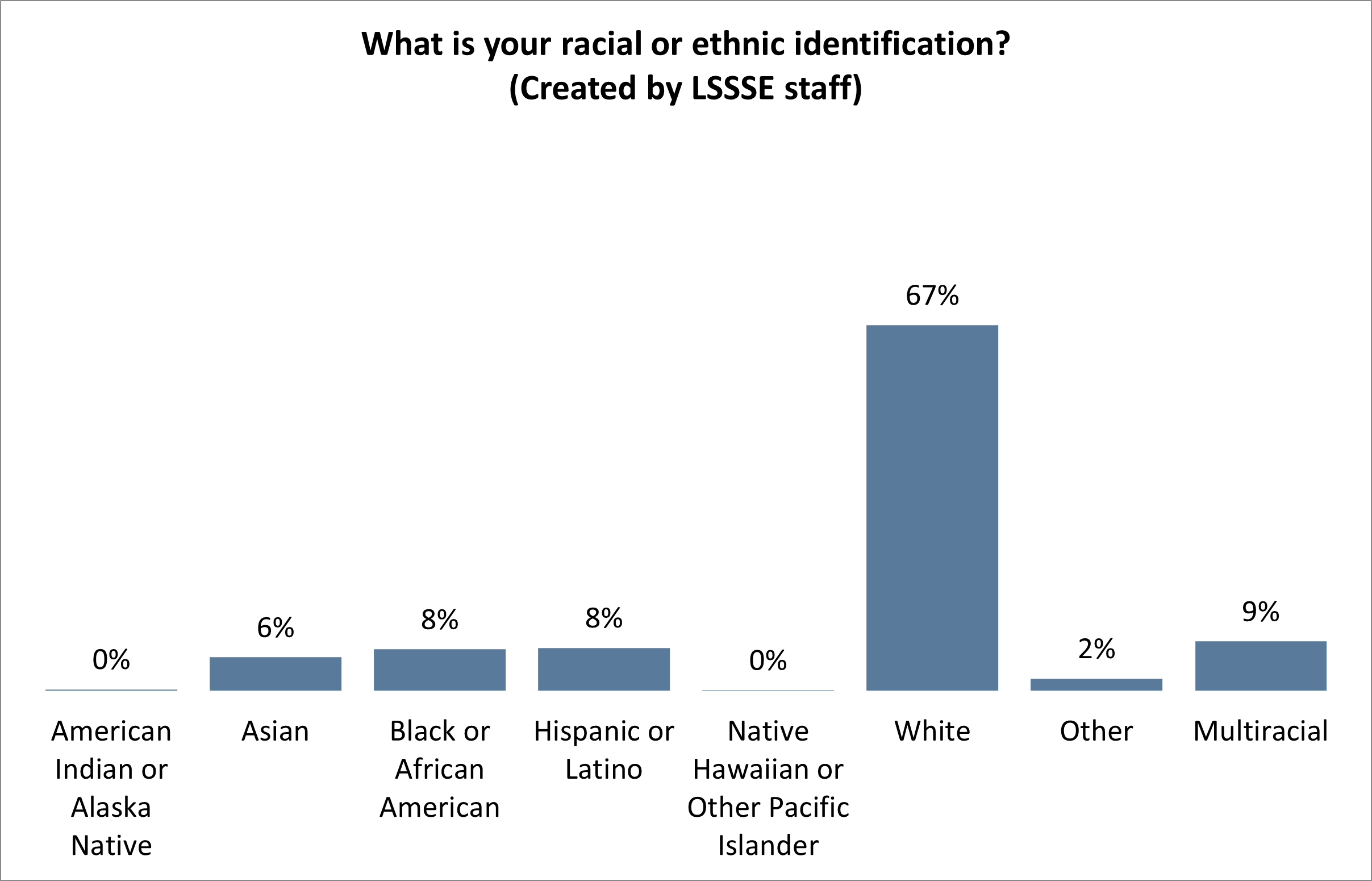

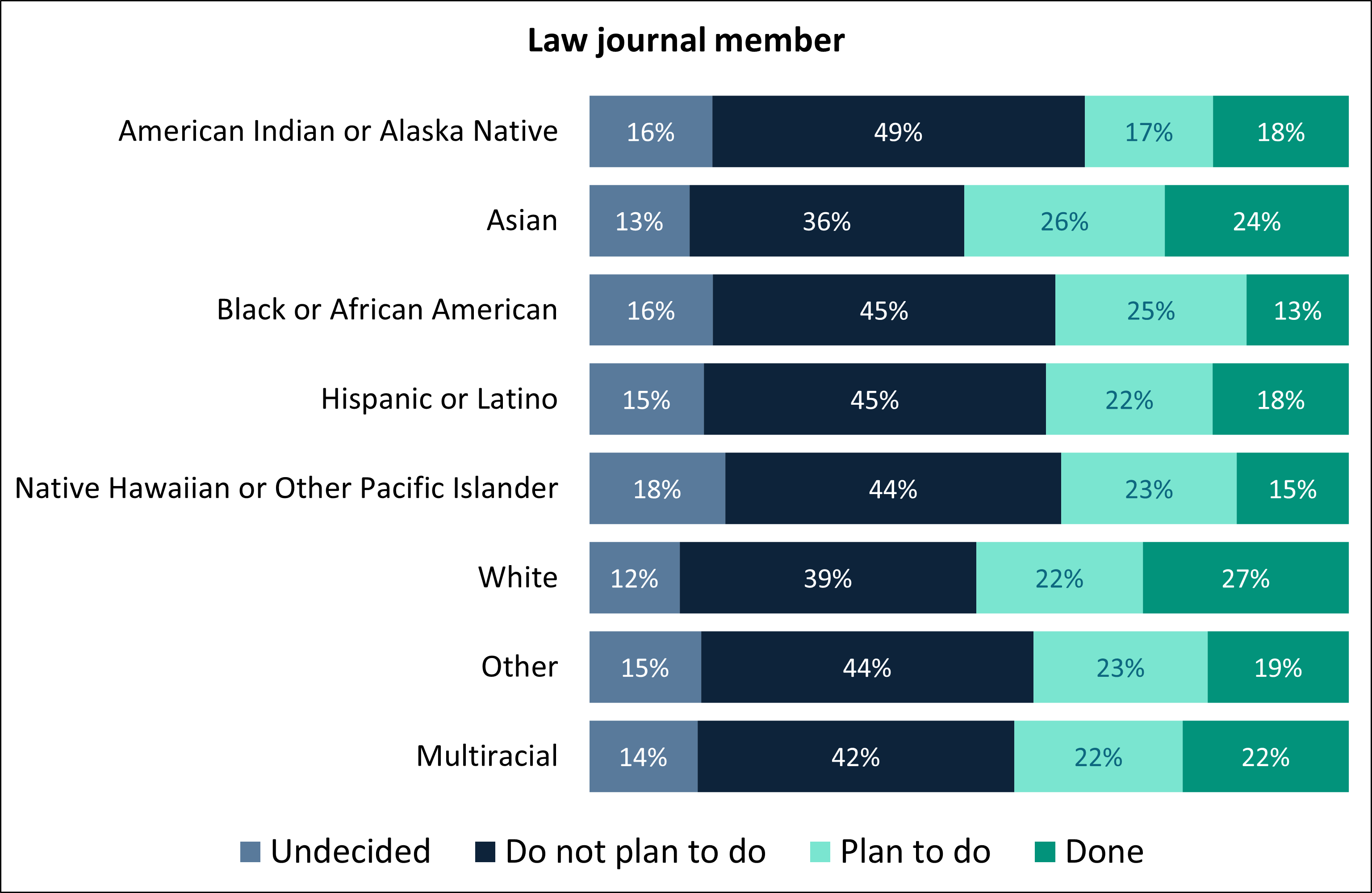

LSSSE data reveal that roughly 8% of current law students are Black. Still, while White students remain the majority (67%), many Black students continue to pursue opportunities to join and lead the law review. Furthermore, there is significant interest among Black students in joining other law journals. Approximately 13% of Black LSSSE respondents note that they have already joined a law journal and an additional 25% note that they plan to do so in the future. Accordingly, the (lack of) participation and leadership of Black law students on law reviews does not reflect apathy.

We believe that law review’s diversity problem must be engaged in the broader context of two complementary lenses: (1) sociopolitical efforts to eradicate racial injustice; and (2) institutional efforts to reform legal education.

On the one hand, the lens of socio-politics suggests that DEI efforts in law reviews experience the push and pull of racial attitudes and perceptions across the nation. For example, researchers have shown that although the election of President Barack Obama in 2008 improved the public’s perception of Black people’s work ethic and intelligence, racial attitudes became more polarized between 2009 and 2013, coinciding with an increased number of racially motivated killings of Black people nationwide. Nationwide calls for racial reckoning in the summer of 2020 after the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, among others, coincided with a dramatic uptick in Black EICs in 2021 and 2022. Accordingly, at least one driver of the increased attention to DEI issues in law reviews during the past ten years may be attributed to the increased attention nationwide to racial justice issues since President Obama’s election.

On the other hand, DEI efforts in law reviews also experience the push and pull of racial attitudes and perceptions across their law school community, including the views and attitudes of their faculty. Consider the current project of “building an Antiracist law school,” as Dean Danielle M. Conway of Penn State Dickinson Law puts it, that has been decades in the making. That effort has only been amplified in recent years, with law faculty increasingly prioritizing racial justice in their teaching and scholarship. Therefore, another driver of the increased attention to DEI issues in law reviews during the past ten years could be law professors’ increased attention to modern social movements, such as the Movement for Black Lives.

We argue that there are three fundamental drivers of law review’s diversity problem, with implications not just for law reviews, but for legal education writ large. First, there is confusion on the purpose of DEI. The purpose of DEI for law reviews is not solely to increase diversity on the law review roster to enhance the learning experience of students on the journal. A deeper purpose of DEI, we argue, is to realign the distorted function of the law review with its ideal purpose. While one of law review’s fundamental purposes is to promote scholarly discourse on law and law reform to promote the public’s interest, in practice, many law reviews serve merely as a gatekeeper for elite law practice and prestigious clerkships.

Second, there is confusion on the role that DEI plays in the legal education experience. The role of DEI for law reviews is not merely to increase the equality of opportunities for underrepresented students, nor simply to increase the discussion of marginalized experiences and diverse perspectives of law in public forums. We argue that the role of DEI is to articulate a more ambitious conception of “equity” in law, political economy, and legal education. As Lani Guinier argued, the very concept of meritocracy that governs how racially and ethnically minoritized students pursue equitable outcomes on the pathway toward legal practice must be challenged as an historically limited vision of legal education.

Finally, the value of DEI for law reviews has been distorted. The value of DEI is not simply its ability to increase the number of marginalized voices in mainstream legal discourse. DEI efforts must also challenge the culture of mainstream legal discourse altogether. Challenging elitism in the legal profession, we argue, requires a bold critique of the toxic ideologies that color societal views on meritocracy and leadership, which can influence the very color of law review itself.

To be sure, the recent wave of Black law review EICs is a bold step in the right direction. However, more work remains to dismantle the gatekeeping function of law reviews and transform it into an educational space open to all law students and all members of the broader community.

Guest Post - Digging Into Data: The Gems at the Back of the Bookstore

Digging Into Data: The Gems at the Back of the Bookstore

Digging Into Data: The Gems at the Back of the Bookstore

Tracy Turner

Associate Dean for Student Learning Outcomes

Graphs by Bradley Yost, Manager of Institutional Research

Southwestern Law School

For a student-focused school like my institution, Southwestern Law School, LSSSE survey results can sometimes be treated as an affirmation that we are doing a good job when our averages in desirable categories exceed the LSSSE average and the averages at our peer schools. And with the addition of an in-house institutional research expert, we have been able to start digging beneath the surface of the results by disaggregating data not only by demographics but also by cross-referencing answers to different questions within the survey. It feels like the difference between window shopping and burying our heads in the boxes stashed in the back of the bookstore where the real gems are hiding.

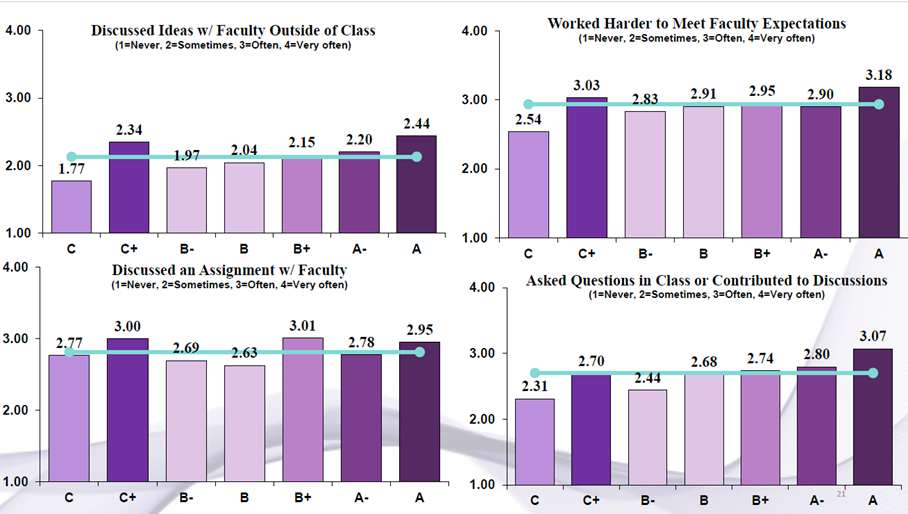

Sometimes the results merely confirmed suspicions. For example, student assessment of their relationships with faculty correlated with their experience in receiving prompt feedback on assignments and with their perception of support for their success. Other times, however, the results were surprising and raised interesting questions about how to support our students.

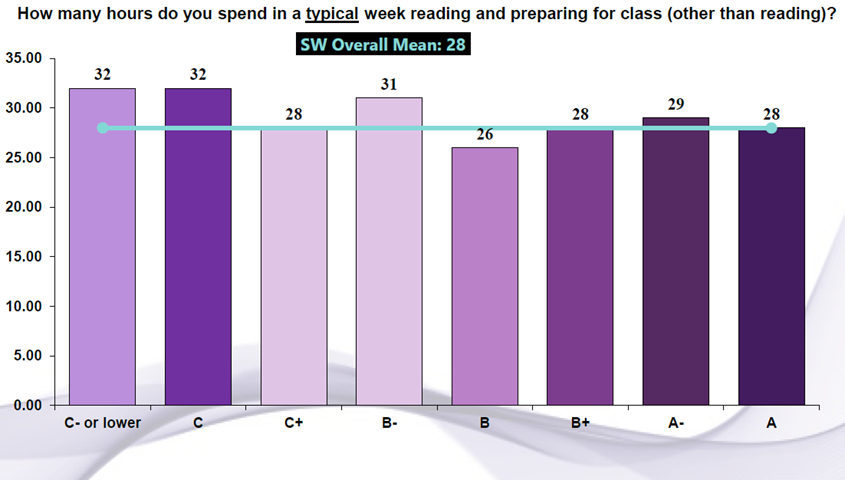

While we saw that GPA correlated fairly well with preparation, engagement, and self-perception of working hard, the correlation was not consistent: in each of these categories, our C+ students reported spending more time and working harder than the B students and in fact were very close to our A students. At C- and below, the correlation was strong.

What is happening with these C+ students that disrupts the correlation and is there something we can do to help them see some of the same payoff from effort that our higher-performing students experience?

What is happening with these C+ students that disrupts the correlation and is there something we can do to help them see some of the same payoff from effort that our higher-performing students experience?

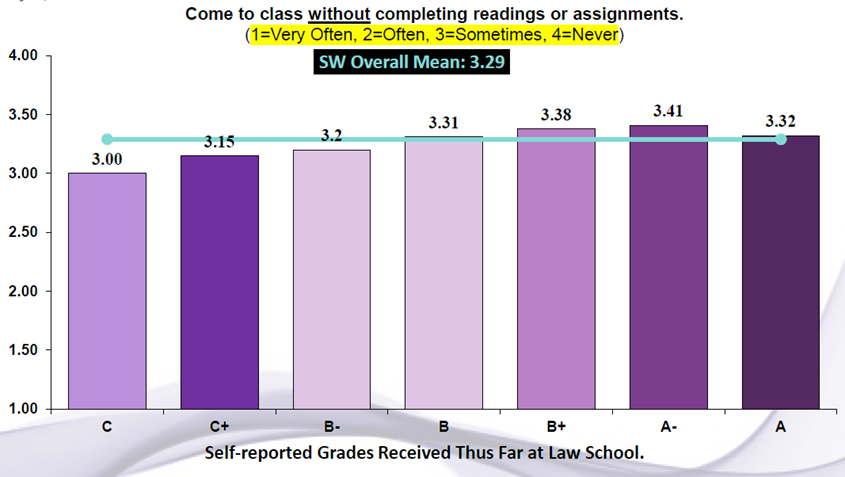

Another important anomaly that surfaced was that students with lower GPAs reported spending more time reading than did B-level students and above, but at the same time reported that they failed to complete the reading more often.

Does this possibly suggest that less assigned reading might enable better performance in this category of students? Whatever the answer, the evidence that our lower-performing students are working hard but struggling to keep up with the reading is important information to consider in how we structure our required curriculum and individual course assignments.

Does this possibly suggest that less assigned reading might enable better performance in this category of students? Whatever the answer, the evidence that our lower-performing students are working hard but struggling to keep up with the reading is important information to consider in how we structure our required curriculum and individual course assignments.

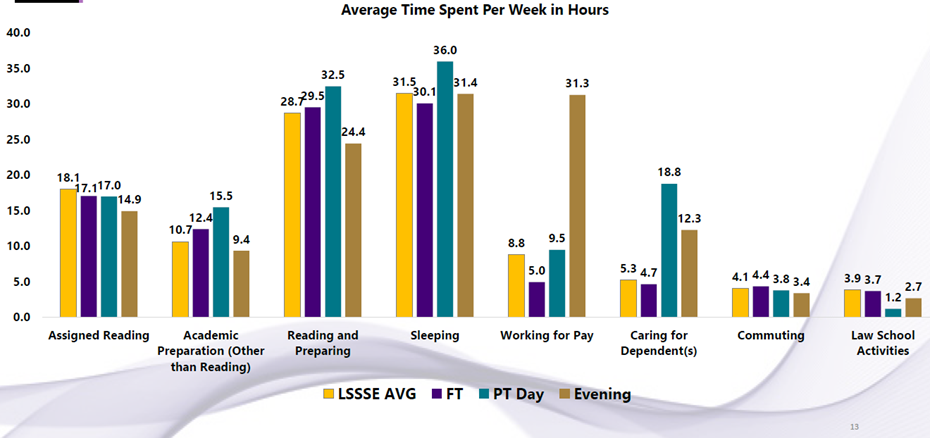

As one last example, we also compared the time that students reported spending on various school-related and personal tasks and learned that, on average, students spent more time commuting than engaging in extracurricular activities, and this result came years after building student housing on campus to address this very issue. And even our full-time students reported spending slightly more time on outside work than on extracurriculars.

This raises an important question about whether we could imagine interventions to decrease our students’ need to commute and find outside work. Next year, Southwestern will also be able to compare LSSSE responses and academic performance data from its in-residence program to data from its new fully online J.D. program ( https://www.swlaw.edu/Online).

This raises an important question about whether we could imagine interventions to decrease our students’ need to commute and find outside work. Next year, Southwestern will also be able to compare LSSSE responses and academic performance data from its in-residence program to data from its new fully online J.D. program ( https://www.swlaw.edu/Online).

We are only on round one with this level of disaggregation, and it will take one or two more repetitions before the information is truly actionable but the questions and thinking it has raised have already challenged some assumptions.

Another new way to use LSSSE that we have discovered is as part of our learning outcomes assessment process. Student answers regarding the extent to which they have been asked to synthesize and organize information and apply theories and concepts to new problems and situations serve as a useful indirect assessment tool for our learning outcomes on legal analysis. Although our initial experience with this was much like our prior experience with survey results – mostly confirming that we are doing well – we can next disaggregate these responses like we have with the other examples mentioned above to discover whether there are GPA correlations or class preparation or engagement correlations. We can thus examine whether student experience with these learning outcomes is consistent and which variables may have an impact.

These new approaches to LSSSE results are helping us use the survey as it was intended to be used – for discovery and improvement in our mission to maximize the success of our students.

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Erika K. Wilson

Professor of Law, Wade Edwards Distinguished Scholar, and Director of the Critical Race Lawyering Civil Rights Clinic

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 143 S. Ct. 2141 (2023) arguably ended race-conscious admissions policies as we know them. While the Court did not expressly overrule diversity as a compelling state interest, it did find that the way in which Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were using race to achieve diversity was unconstitutional. The majority opinion observed that universities undermined their stated interest in obtaining a racially diverse class by relying upon “opaque racial categories.” It identified as particularly problematic categorizing all Asian applicants together with no distinctions made between South and East Asians; the arbitrariness of the Hispanic categorization; and the under inclusiveness of the Middle Eastern classification. Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion made a similar observation with respect to the categorization of Black students:

The “Black or African American” category covers everyone from a descendant of enslaved persons who grew up poor in the rural south, to a first-generation child of wealthy Nigerian immigrants, to a Black-identifying applicant with multi-racial ancestry whose family lives in a typical American suburb.

Gorsuch’s critique is salient because the original purpose of race-conscious affirmative action programs was to remediate the multi-generational effects of slavery and the afterlives of slavery. Yet, as documented by legal scholars like Angela Onwuachi-Willig, in the early 2000s Black students at elite universities were overwhelmingly mixed-race students, or first- or second-generation Black Americans, meaning their parents and/or grandparents were immigrants. Lani Guinier and Henry Gates raised concerns in 2004 because only one-third of Harvard’s Black undergraduate students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America, descendants of persons enslaved in America.

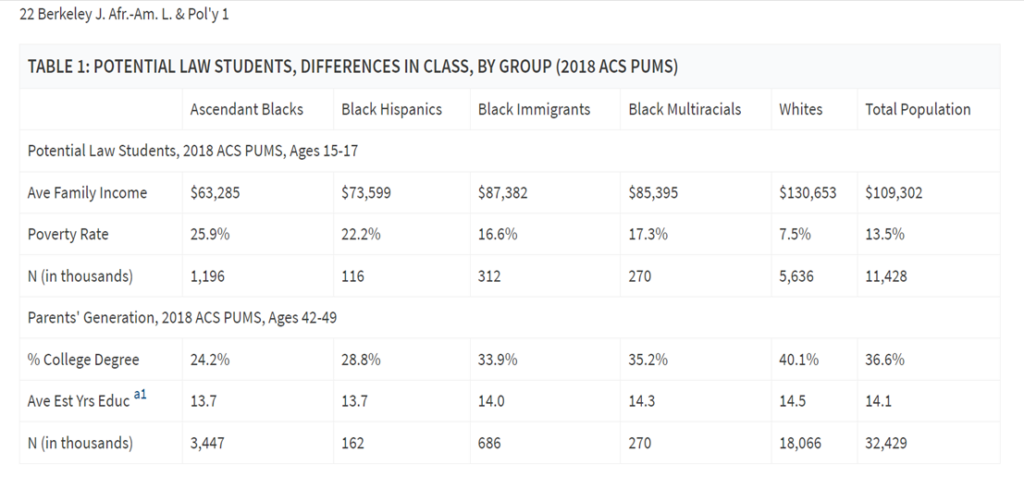

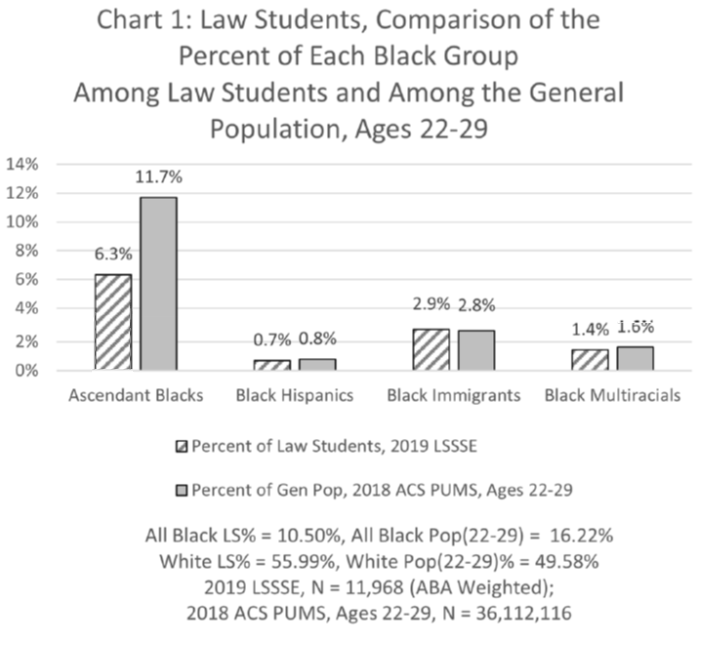

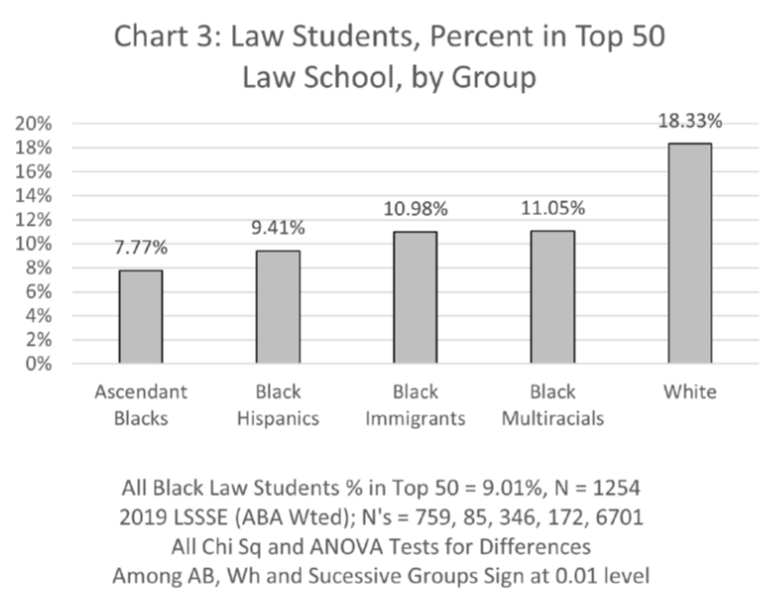

Recent research by Kevin Brown and Kenneth Dau-Schmidt relying on LSSSE Survey data shows that not much has changed since the early 2000s. Similar patterns of disproportionate representation of what Brown and Dau-Schmidt call “ascendant Blacks” (those with two American-born Black (non-biracial) parents) exists in law school enrollment today. The data show three noteworthy trends:

First, while structural racism impacts all Black people in America, it impacts some groups more acutely. As they write in their article, ascendant Black law students have lower average family incomes, higher poverty rates, and are less likely to have parents with a college degree.

Second, all Black people, except Black Immigrants (defined as Black people with at least one parent not born in America), are underrepresented among law students; furthermore, the extent of underrepresentation is much worse for ascendant Black law students than for other Black law students.

Third, ascendant Black law students are underrepresented at Top 50 law schools relative to their representation within the population of Black people in America, and relative to all other groups of Black law students.

The data and their implications should inform the path universities take to reinvent their affirmative action programs. Diversity is still recognized as a compelling state interest. Universities can and should fashion admissions programs that seek to increase representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. To be sure, they should also continue to make efforts to increase representation of all Black groups because race remains a salient and undeniable barrier for all Black people in America. Yet the unique burdens and history of subordination linked directly to American slavery imposes a special remedial obligation on universities to provide access to Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. This is especially true for elite universities such as Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that directly benefited from slavery.

In Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in Students for Fair Admissions, he offers a potential Constitutional path for doing so. He suggests that a classification consisting of descendants of persons enslaved in America is not a racial category. He contends that:

[The 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Act ] applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not [B]lacks writ large. And, because “not all [B]lacks in the United States were former slaves,” “ ‘freedman’ ” was a decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.

His comments, as other scholars have noted, raise questions as to the legality of an affirmative action program centered on descendants of persons formerly enslaved in America, as such a categorization may not be subject to the same level of heightened scrutiny as a race-based classification. Nonetheless, Thomas’ assertion that “freedmen” was not a racial categorization is admittedly dubious. But such a targeted program might also be justified under the remedial justification for race conscious policies. Thus, universities should take Thomas seriously. They should fashion admissions programs aimed at increasing the representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. LSSSE data and history demonstrate the normative case for doing so.

Guest Post: Legal Education During the Pandemic: The Experiences of Latinx Law Students

Raquel Muñiz

Assistant Professor

Lynch School of Education & Human Development and School of Law (by courtesy)

Boston College

Andrés Castro Samayoa

Associate Professor of Higher Education

Lynch School of Education & Human Development

Boston College

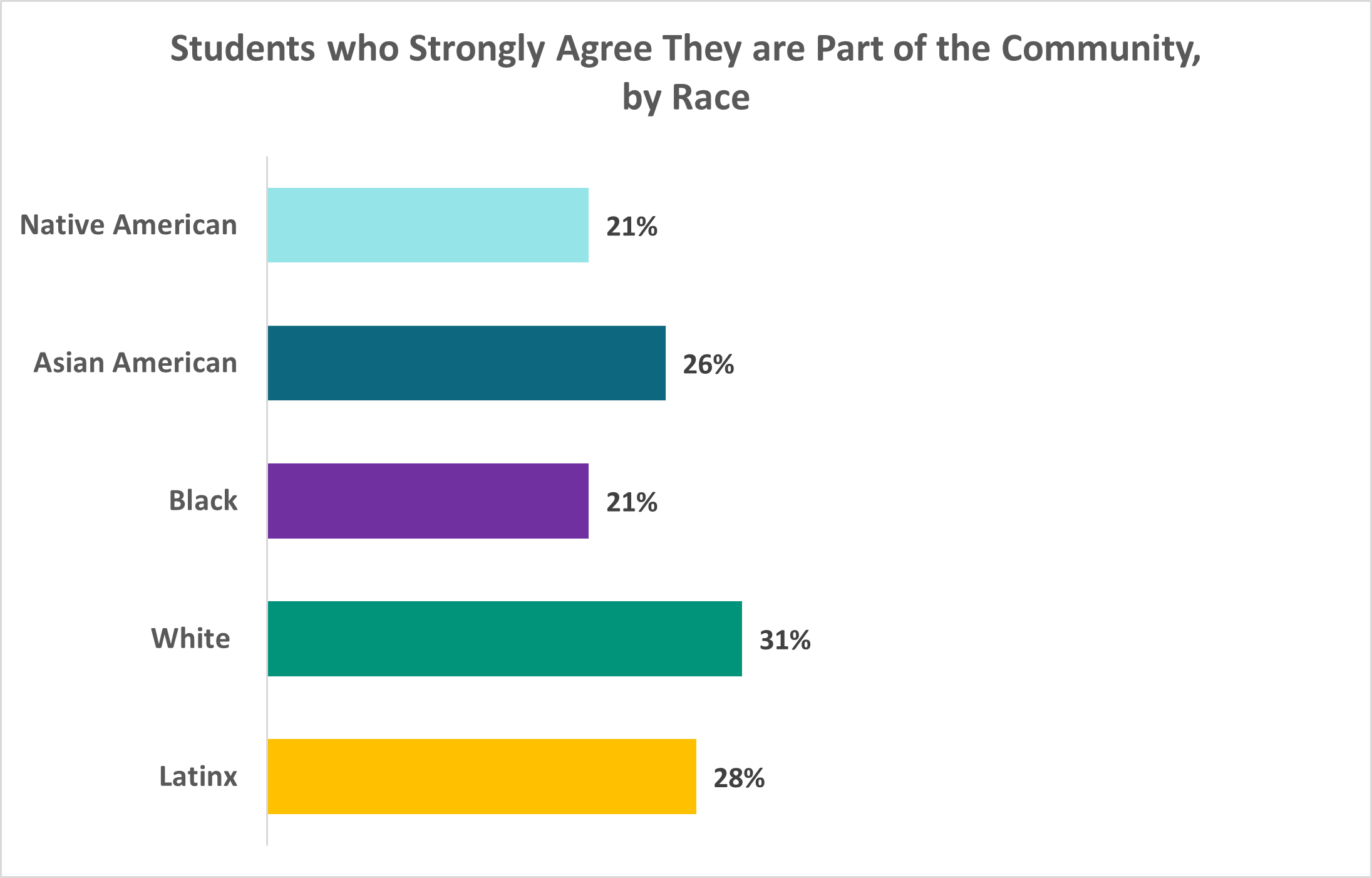

Latinx people remain underrepresented in the legal profession and experience exclusion and marginalization during law school. The culture and environment unique to legal education present challenges to their experiences. For instance, LSSSE data show that in 2020 only 28% of Latinx law students strongly felt part of their law school community and only 1 out of 5 Latinx law students reported feeling comfortable being themselves at their institutions. Moreover, while Latinx representation in law school has increased over time, they carry greater financial burdens. LSSSE has found that Latinas are more likely to borrow over $200,000 than men of the same ethnicity or than women from any other background. This troubling trend remains consistent in longitudinal reporting. Latinx law students remain a student population in need of structural support to access and succeed in law school as they are socialized into the profession.

In 2019, we began a project to understand how Latinx law students across differently ranked law schools (Tier 1, 2, 3 & 4) valued their legal education. We recruited students at law schools enrolling the largest proportion of Latinx law students across each Tier, two schools per tier. In total, we interviewed 81 law students: T1 (23 students total), T2 (23), T3 (24), and T4 (11). Our data collection extended into 2020, giving us a rare insight into how Latinx law students made sense of their legal education as the height of the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded.

Students were generally satisfied with the prompt response that their law schools employed as they shifted from in-person to virtual classes. They also agreed that a law degree is a timeless degree because, as a student noted, “[T]he world is always going to need attorneys.” Additionally, law students experienced the same disruptions as other students—disruptions to their routines, challenges concentrating and finding a space to study, as well as loss of community with other students, faculty, and staff. One noted: “It’s a loss of sense of community. It’s hard for you to keep in touch with your peers. It’s very difficult. It’s kind of like you’re just watching a YouTube video of the doctrine.” These trends align with LSSSE’s report, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, which revealed numerous challenges including increases in loneliness and inability to concentrate.

In-depth qualitative interviews with 2Ls and 3Ls also revealed how the pandemic amplified challenges endemic to legal education, namely: a zero-sum hypercompetitive environment driven by hierarchical metrics of prestige as proxies of success. Students’ references to these concerns expressed themselves differently depending on their law school’s rankings. Student concerns in Tier 1 law schools centered around whether online courses would impact student learning, grades, bar passage rates, and subsequently law school rankings. Law school rankings were important to students in highly ranked law schools, because they viewed them as deeply intertwined with premium post-graduation employment opportunities. One student articulated this concern, noting:

I think as a law student, it makes me feel better about the money I’m taking off to go to law school, because they’d make me feel like people will want to hire me because of the school ranking. . . . I’m just really concerned about COVID and how that’s going to affect the rankings and schools and the type of student [learning.] I just feel like we’re better students when we do in-person classes. . . . It will affect the bar passage rate and, in consequence, school ranking.

These concerns were magnified in T1 schools compared to other law schools: Students expressed concerns that their law school would fall in the rankings as a result of COVID and that the money they paid (and often, borrowed) to attend a highly ranked law school would not yield results, leading to fewer professional opportunities. Tier 2 law students expressed a more salient concern with disruptions to the relationships they had built through experiential learning and summer placements. They also worried about the high cost of attending law school and whether that was a worthy investment or if COVID would diminish their investment.

In contrast, students in one of the T3 law schools had a heightened awareness of their schools’ lower ranking and worried that jobs in the legal profession would shrink because of COVID and the few positions left would go to students in higher ranked law schools. The second T3 school was heavily focused on public interest law, and students repeatedly noted that their degree post-graduation was even more valuable, because there is an increasing need for lawyers who advocate for the rights of marginalized communities. Concerns over job prospects as a result of the pandemic were consistent in both T4 law schools.

While law schools continued to pivot to online learning and maintain a semblance of structured routine, within-class rankings became a topic of debate fueled by competition. Students in schools with class rankings across all tiers discussed their concerns with the Pass/Fail system adopted by schools. Multiple students shared that the lack of grades would lead to decreased motivation for students to excel academically. Others expressed a preference for grades, because this meant they would be able to outperform their peers and this would benefit their class ranking. This dominant sentiment is captured by a student in a T3 law school:

There's been some concerns about the grading system, because schools nationwide have decided to go to Pass/Fail or Credit/No Credit. . . . [T]hat created a lot of buzz and a lot of anxiety . . . . [There were] Facebook debates on: What’s better? What’s worse? And some folks are saying on Facebook that people of color have it harder and that we should just do Pass/Fail. Whereas my perception of this was: given the fact that I have actually been through a lot personally, I felt like I was actually looking forward to this. Because I felt like people that have not experienced adversity, right now, they’re facing it. And I know what it’s like to have to think on your feet. So, I was thinking to myself, “Well, go ahead, bring on the grades.” Like, we’re just going to see who can do what they can do.

Students’ responses to the early days of COVID reveal how even unexpected global disruptions can serve to further entrench the hyper competitive economy of prestige in preparing future lawyers. Four years into COVID-19, few institutional practices have attempted to curtail these efforts. In the past few months, the specter of artificial intelligence platforms like ChatGPT once again offer an opportunity to reconsider how we can equitably respond to the future of the profession. Will we heed the call?

Acknowledgement: This project was funded by AccessLex/AIR and The Spencer Foundation.

Self-Check: Are We Paying Attention to Developments in the Profession?

Guest Post

Marsha Griggs

Associate Professor of Law

Saint Louis University School of Law

The BlueBook® is in its twenty-first edition and for the last fifteen years has been available online as well as in its original spiral-bound print version.[1] I could not imagine publishing a Law Review article, submitting a court brief, or teaching a Legal Writing course without consulting the most current edition of the BlueBook. Although I don’t care about uniform citation guides for my day-to-day writing tasks, I understand the expectation of proper citation for formal writing projects.

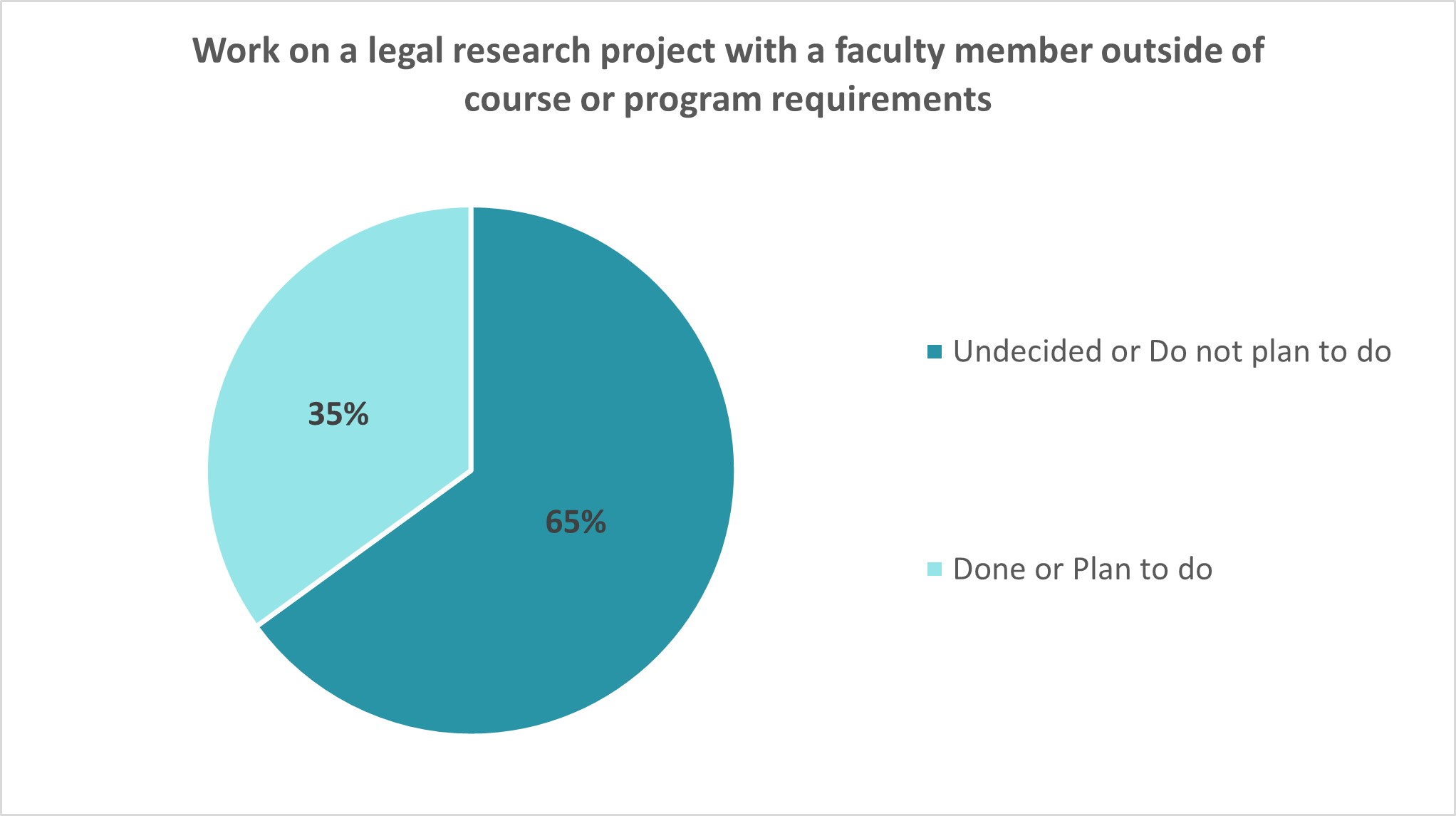

To meet that expectation, I gratefully rely upon my research assistants and the meticulous eye of journal editors. I am out of practice with my “blue booking” skills, because I consistently hire someone else to do it for me. I know that many other mid-career faculty and law practitioners can relate. Thankfully, LSSSE Survey data show that law students benefit from working on legal research tasks with faculty outside of class assignments. Although student research responsibilities for faculty and journals often fall outside the experiential education radar, these tasks are important to practice readiness.

While it is perfectly fine for me to outsource necessary cite checking to a student or even to an A.I. tool like ChatGPT, I am still ultimately responsible for my written product. The same is true about our professional responsibilities as lawyers. We can and should rely on available technology and skilled providers who can aid us in delivering legal services and establishing and enforcing laws and policies. But we must do so with a conscious awareness that tools, practices, policies, and laws are constantly subject to change.

Lawyers and legal educators have an ethical obligation to engage in continuing study and education to keep abreast of changes in law practice and legal rules, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.[2] That obligation includes keeping up with changing rules for attorney licensure. Yet very few law professors and even fewer attorneys in practice understand the previous and proposed sweeping changes in attorney admission, including who creates and controls the bar exam.

Outsourcing a specific legal task—like research or cite checking, is not the same thing as outsourcing a regulatory function—like licensing attorneys. In a forthcoming article, Outsourcing Self-Regulation, I address how states have contracted with outside providers to produce bar exam questions and to score the exams. Like my outsourced blue booking, it saves time and results in a higher quality product. But when the outsourcing of a responsibility is combined with inattention or lack of supervisory accountability, it becomes delegation of a regulatory power or duty. Such a shifting of regulatory authority threatens the autonomy of the legal profession.

Today, bar exam questions are almost uniformly written and selected by the NCBE. [3] The NCBE has successfully lobbied for a single unform exam to replace the varied individual state law exams. The widespread adoption of a Uniform Bar Exam has privatized bar admission to the point that states no longer have control (or even input) into the content, scope, or timing of their licensing exam. The privatization of the bar exam is at odds with the cornerstone principle of resolute self-regulation and freedom from external influence.

The planned debut of the NextGen bar exam in 2026 threatens to further weaken the judicial autonomy in attorney admission.[4] Dangerously little is known about this new exam and law schools too are fully at the mercy of NCBE for crumbs of information about the next exam. We cannot effectively help our students to prepare for licensure if we ourselves are unfamiliar with the licensure exam and its format and cannot verify its validity.

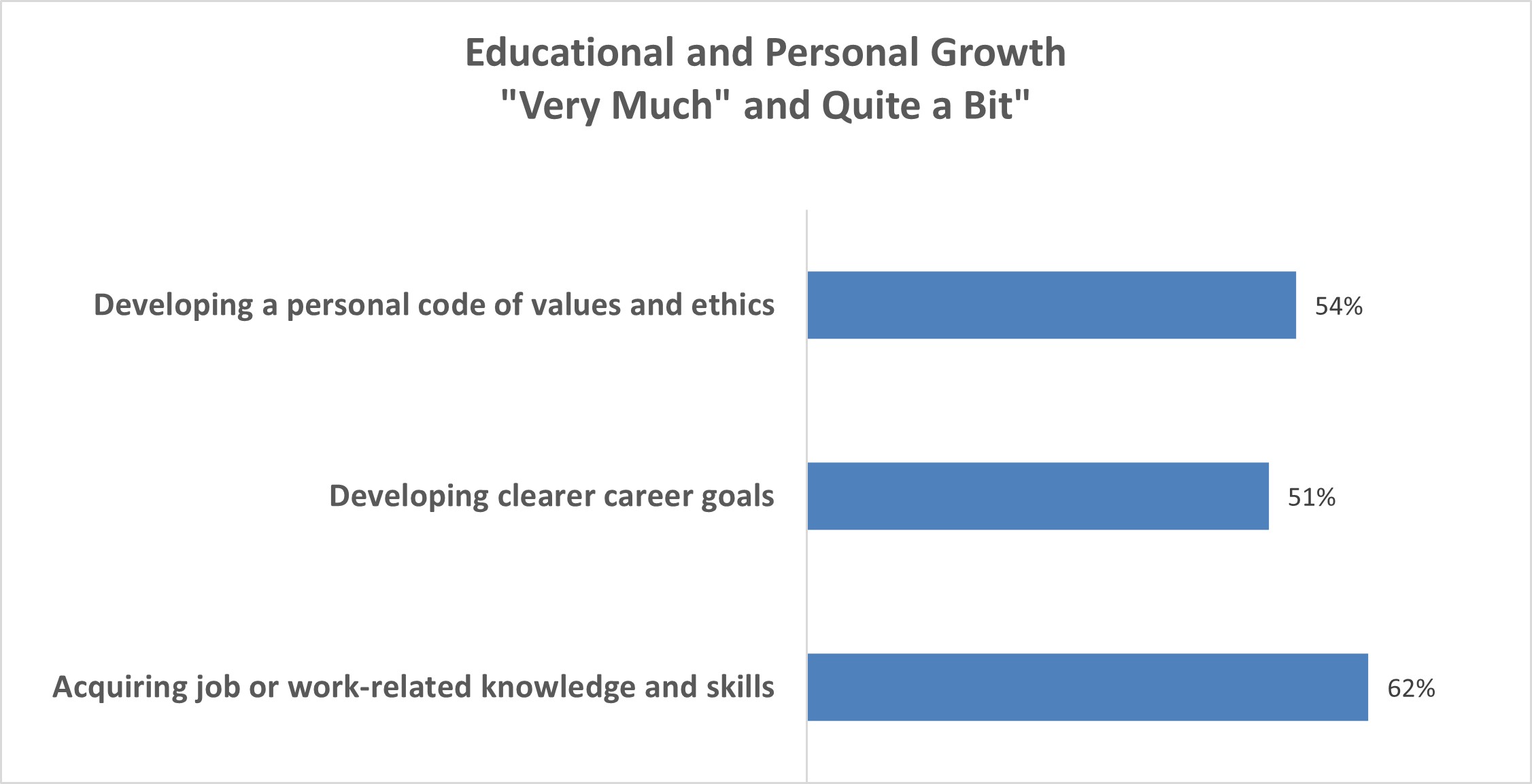

The LSSSE Survey data show that law students feel that law schools have generally prepared them for work-related tasks and supported them in developing career goals and personal ethics.

A quantifiable component of preparing law students for the practice of law is preparing them for the bar exam that allows them entry into law practice.

The pathway to becoming an attorney in the United States typically involves attending and graduating from law school, and successful completion of some competency assessment. All but a few U.S. jurisdictions use performance on a bar examination as a proxy for minimum competence to practice law. Since the genesis of licensure by examination, the format, content, scoring, and source of bar exams have been contentious issues in the legal profession.[5] The arguments for and against the use of bar exams are too great to list or summarize here, but—however it is measured—law schools are responsible for ensuring that their graduates are minimally competent to deliver legal services directly to clients upon completion of the program of legal education.

As members of a self-regulated profession, we have a responsibility not only to know about the scope of the regulatory exam, but also to set the standards for what the regulatory exam should measure and how it should do so. We must pay attention to developments in attorney licensing if we aim to continue to meet the needs of our students who will pursue licensure.

___

[1] The BlueBook: A Uniform System of Citation R.15.8(c)(v), at 154 (Columbia L. Rev. Ass’n et al. eds., 21st ed. 2020).

[2] American Bar Assoc’n Model Rule of Professional Conduct 1.1 Comment 8.

[3] The National Conference of Bar Examiners is a not-for-profit corporation with its principal office in Wisconsin. https://www.ncbex.org/about/media-kit/

[4] https://nextgenbarexam.ncbex.org/

[5] See e.g. Joan W. Howarth, Shaping the Bar: The Future of Attorney Licensing (2023), and Marsha Griggs, Building a Better Bar Exam, 7 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 1 (2019).

The Power of Critical Legal Research

The Power of Critical Legal Research

Priya Baskaran

American University Washington College of Law

Every year students ask me which classes are “the most important” to prepare them for successful and fulfilling legal careers. Should they focus on Bar classes or load up on Business Law for future corporate practice? Or should they opt for a seminar that will really engage their interest in human rights or environmental justice? Inevitably many students seek me out because as a professor at the top ranked clinical program at American University Washington College of Law, I actively engage in the practice of law. I also closely supervise and ultimately grade my clinic students on their own lawyering skills. The students who seek my advice do so because they are keen to acquire the skills and training to lawyer well. My response often surprises students: Take an advanced legal research class and focus on Critical Legal Research.

Legal research is too often conflated with navigating a commercial search database as quickly as possible. In reality, legal research is a complex, dynamic, and iterative process that requires a combination of critical thinking, analysis, strategy, and perseverance. Legal research is also a large part of the average attorney’s work life, particularly early career attorneys.[1] Finally, and most importantly in my mind, developing strong legal research foundations is essential to solving complex, real-world problems. This latter point is only increasing in relevance with the continued growth of generative AI.

Legal research provides students with a primer in intersecting legal regimes, showcasing how various subjects we teach in self-contained classes actually combine and impact the facts of any given case or circumstance.[2] Legal research then teaches students how to critically examine and sort these intersections into tiers of relevance for their various research questions and research tasks. Finally, legal research focuses on creating search plans and strategies. This includes understanding where they find this information – specialized secondary sources, primary authorities practice related resources, even specialized databases. Students also actively analyze and evaluate the results of their searches, making thoughtful and critical determinations when sorting and prioritizing information.[3]

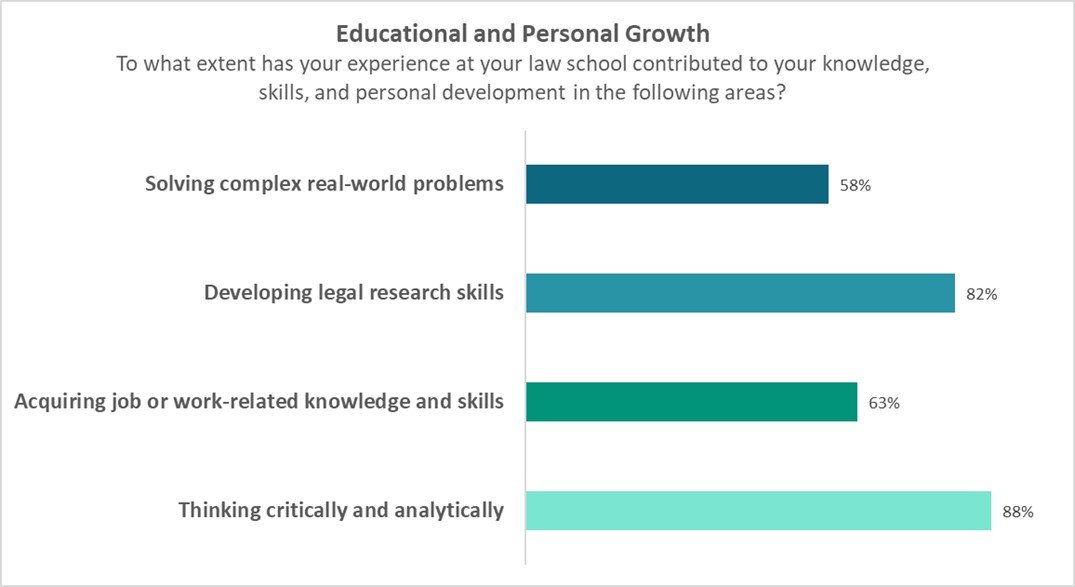

A properly taught legal research class excels in equipping students with the skills essential to good lawyering: 1) complex problem solving by researching messy or novel situations, 2) practical training in a core lawyering skill – legal research, 3) the ability to engage in active learning by directly researching, and 4) developing critical thinking and analysis skills. We see from LSSSE data that a majority of law students do learn these skills in law school.

*Students responding “quite a bit” or “very much”

In particular, a number of schools are increasingly using critical information literacy and Critical Legal Research to teach legal research. Critical legal information literacy is a pedagogy that challenges conceptions of legal research databases as neutral or comprehensive. Instead, critical information literacy teaches students that legal information is intentionally curated and categorized, often for commercial purposes.[4] This teaches students to be careful, thoughtful readers when their search results skew in favor of the status quo. Similarly, Critical Legal Research (CLR) builds on critical legal information literacy and incorporates critical legal theories and methodologies into the legal research process.[5] CLR challenges students to rethink their research questions, research strategies, and develop more expansive and thoughtful research plans in order to account for systemic bias. CLR underscores how the existing commercial search databases can entrench hegemonic interests, harming novel arguments that can advocate for more just outcomes.[6]

Take for example the case of a retail employee in June 2020. The employee works for a popular coffee chain that has been deemed “an essential business” during the COVID-19 epidemic. The employee routinely has to interface with customers who refuse to follow the safety protocols required by the county health department, including masking. Her manager requires employees still serve these customers despite the violation of the county health code and the CDC requirements. The employee finds her current work situation untenable for a number of reasons. First, she is deeply troubled by the request to break county law by violating the health department’s mandate. Second, she is concerned for her safety and the safety of her family (including an immunocompromised dependent). She feels like she has no choice but to quit her job but is worried about qualifying for unemployment insurance benefits.

We can immediately issue spot many complicated legal problems that will arise from this case. We can also identify the person being impacted by these “justice” issues – a worker facing both economic precarity and unsafe working conditions. Finally, we should be able to recognize that legal precedent will be exceedingly thin as June 2020 was still the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Building a case with little to no case law requires creative thinking and creative research strategies. What other sources may prove informative or be persuasive? Are there corollaries we can draw to other illnesses or other jurisdictions we should use to build our argument? Finally, we must identify and discuss that justice – when it goes against the dominant interests – requires creative and tireless advocacy on the part of the attorney.

Moreover, the continued growth of generative AI requires that we are even more thoughtful in training students.[7] A poorly trained student will use generative AI as a crutch, adding minimal to no value and simply regurgitating the algorithms findings. A well-trained researcher will identify the shortcomings of the AI tools, creating a comprehensive search plan and strategy that acknowledges and mitigates these flaws. For example, an AI tool may write a briefing memo summarizing the findings and state that the worker has little precedent and therefore a weak case. A well-trained researcher will be able to understand why this AI argument is insufficient for the client and for greater justice. The researcher may even be able to use this AI answer to play devil’s advocate, building a more creative response to counter the points generated by the status quo algorithm.

There is no shortage of conversation surrounding AI in law schools. In addition to discussing academic integrity and ethics, we must use this moment to explore critical pedagogies. How can we as professors help our students understand the blindspots of commercial AI? How can we train them to become better thinkers, lawyers, and advocates by exposing them to the limitations and injustice implications of both AI and traditional research? The answer may lie in leveraging critical legal information literacy and CLR in our own classes and pedagogies.

Although legal research is often limited to the first year curriculum, there are ample opportunities for instructors to engage with the topic in other courses. My forthcoming article, Searching for Justice: Incorporating Critical Legal Research in Clinic Seminar, includes a bibliography of scholarly work and pedagogical tools created by librarians and experts in the field. Professors can and should scaffold student learning by leveraging Critical Legal Research within their pedagogies, training more thoughtful and critical attorneys.

__

[1] Noting that new attorneys spend an average of one third of their time researching. Steven A. Lastres, Rebooting Legal Research in a Digital Age 3 (2013), https://www.lexis nexis.com/documents/pdf/20130806061418_large.pdf [https://perma.cc/SH5Q-Z2D3].

[2] THE BOULDER STATEMENTS ON LEGAL RESEARCH EDUCATION: THE INTERSECTION OF INTELLECTUAL AND PRACTICAL SKILLS (Susan Nevelow Mart ed., Heinemann, 2014). P. xii.

[3] Sarah Valentine, Legal Research as a Fundamental Skill: A Lifeboat for Students and Law Schools, 39 U. Balt. L. Rev. 173, 201 (2010).

[4] Yasmin Sokkar Harker, Legal Information for Social Justice: The New ACRL Framework and Critical Information Literacy, 2 Legal Info. Rev. 19,43 (2016-2017).

[5] .Nicholas F. Stump, Following New Lights: Critical Legal Research Strategies as a Spark for Law Reform in Appalachia, 23 Am. U. J. Gender Soc. Pol'y & L. 573, 603 (2015); Nicholas Mignanelli, Critical Legal Research: Who Needs It?, 112 LAW LIBR. J. 327 (2020).

[6] Nicholas F. Stump, COVID, Climate Change, and Transformative Social Justice: A Critical Legal Research Approach, 47 WM. & MARY ENVTL. L. & POL’Y REV. 147 (2022).

[7] For a fuller exploration of the intersection between generative and legal research, I recommend reading: Nicholas Mignanelli, Prophets for an Algorithmic Age, 101 B.U. Law Rev. 41, 44 (2021).

Guest Post: Celebrating Asian-Americans: Reflections on Solidarity and Success in the Sunlight

Cyra Akila Choudhury

Professor of Law

FIU College of Law

Center for Law and Digital Technologies, Leiden University

Asian Americans have been in the news a great deal in the last several years. This year has been the year for Asians in the movies. Over the pandemic years, Asians and Asian Americans were in the news regularly for being victims of racial harassment and violence. That violence reached its extreme in the Atlanta massacre of six Korean American women working at a spa. The brief outpouring of support and solidarity after the shootings were welcome but not sustained. Within months, Asians went back to being a marginal minority group.

Even though we are the fastest growing minority, too often, we are only given attention in extraordinary moments: when we are the agents (Oscar winners, school shooters) or objects (victims of violence) of spectacular events. The most recent sustained attention given to Asian Americans has been in the context of the legal attacks on affirmative action.[1]

As Asians, we occupy the spotlight but not the sunlight, solidarity ebbs and flows, and our excellence is a double-edged sword. In this blog post, I reflect on the ways in which we have become agents for change in ways that overcome the binary glare of the spotlight or dark of its shadow. Asians have practiced and should continue to commit to radical solidarity both among ourselves and with other groups even as we unapologetically embrace our excellence. I offer these reflections as part of an ongoing conversation about what it means to be Asian American—an umbrella that includes a diverse group of people—in this moment.

- Seeking the sunlight not the spotlight

We are used to not being seen and not attracting attention to ourselves. Psychologist Jenny T. Wang writes in Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans,[2] that safety was one of the primary needs of her immigrant family. Safety meant following the plan of achieving stability and success without fuss. Often this means that we keep our heads down and get the job done, sacrificing what we truly love for the sake of duty. The light is shone on us by others when they perceive something worthy of notice.

In short, unless we are winning Oscars, running Google, or being massacred, people really don’t notice Asians. This is the spotlight effect. An external gaze that lights us up temporarily. As law students and lawyers, this might happen when we win an award or a big case. But what about when we’re not winning something? Asians deserve the sunlight and not the spotlight. That is to say, rather than being content with attention primarily when we achieve excellence, we deserve to be visible and present just as we are. Living in the sunlight also means being willing to be seen in our various workplaces and in society. Raising our hand in class, speaking in our own voice, running for public office, applying for promotion, and owning our histories and accomplishments.

- Practicing radical solidarity

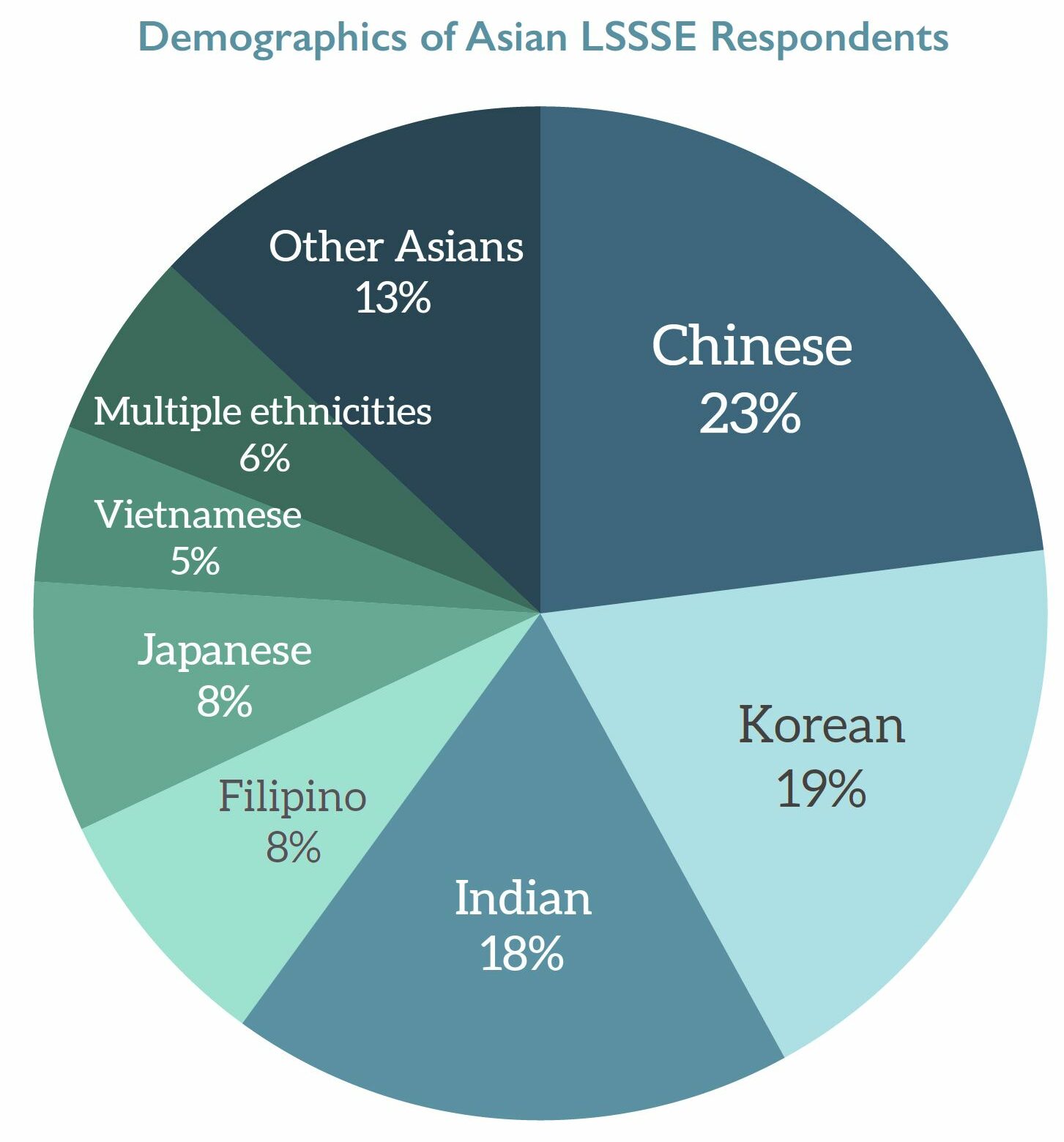

Asia is a vast geography with ancient civilizations. “Asian” is not a race, a cultural group, nor a linguistic group. Asian Americans hailing from different parts of Asia are a diverse group with many sub-diasporas. In legal education, for instance, Asian Americans include those with ancestors from China, Korea, India, the Philippines, Japan, and Vietnam. Increasingly, the shared experiences of these communities in the U.S. based on political marginalization, racism, immigration, and some cultural values have led to a growing sense of shared identity as well.

Yet, much more work needs to do be done to forge these nascent bonds. After the Atlanta massacre and the pandemic related violence against East Asian communities, there was a surge of broader recognition that Asian Americans were subjects of racism. This massacre was preceded by the massacre of six Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012. This too was an Asian massacre and yet, we rarely connect the two as anti-Asian racism. Solidarity among Asians in an increasingly polarized political society has become very important if we want to shape and direct change.

Yet, much more work needs to do be done to forge these nascent bonds. After the Atlanta massacre and the pandemic related violence against East Asian communities, there was a surge of broader recognition that Asian Americans were subjects of racism. This massacre was preceded by the massacre of six Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012. This too was an Asian massacre and yet, we rarely connect the two as anti-Asian racism. Solidarity among Asians in an increasingly polarized political society has become very important if we want to shape and direct change.

Asians have been partners in all of America’s struggles: the civil rights movement, labor rights, anti-war protests, and resistance to the War on Terror. We have demonstrated our solidarity with other groups, and we must do the same within our Asian communities as well. Radical solidarity, as I define it, means showing up for the struggle when called. When Black communities call for resistance, we show up. When Latinx communities ask for solidarity, we show up. Same for feminists and LGBTQ communities. We cannot succeed meaningfully in isolation. These struggles overlap within our communities. Moreover, radical solidarity is something we do without taking stock. I recall an acquaintance remarking in response to the Atlanta massacre, “I’d like to support Asians Americans, but they call the cops,” This is the opposite of radical solidarity. It is contingent solidarity and as we all know, fair-weather friends are of limited value. No single group has succeeded without radical solidarity from other groups. Without the civil rights movement, many of us would not even be Americans.

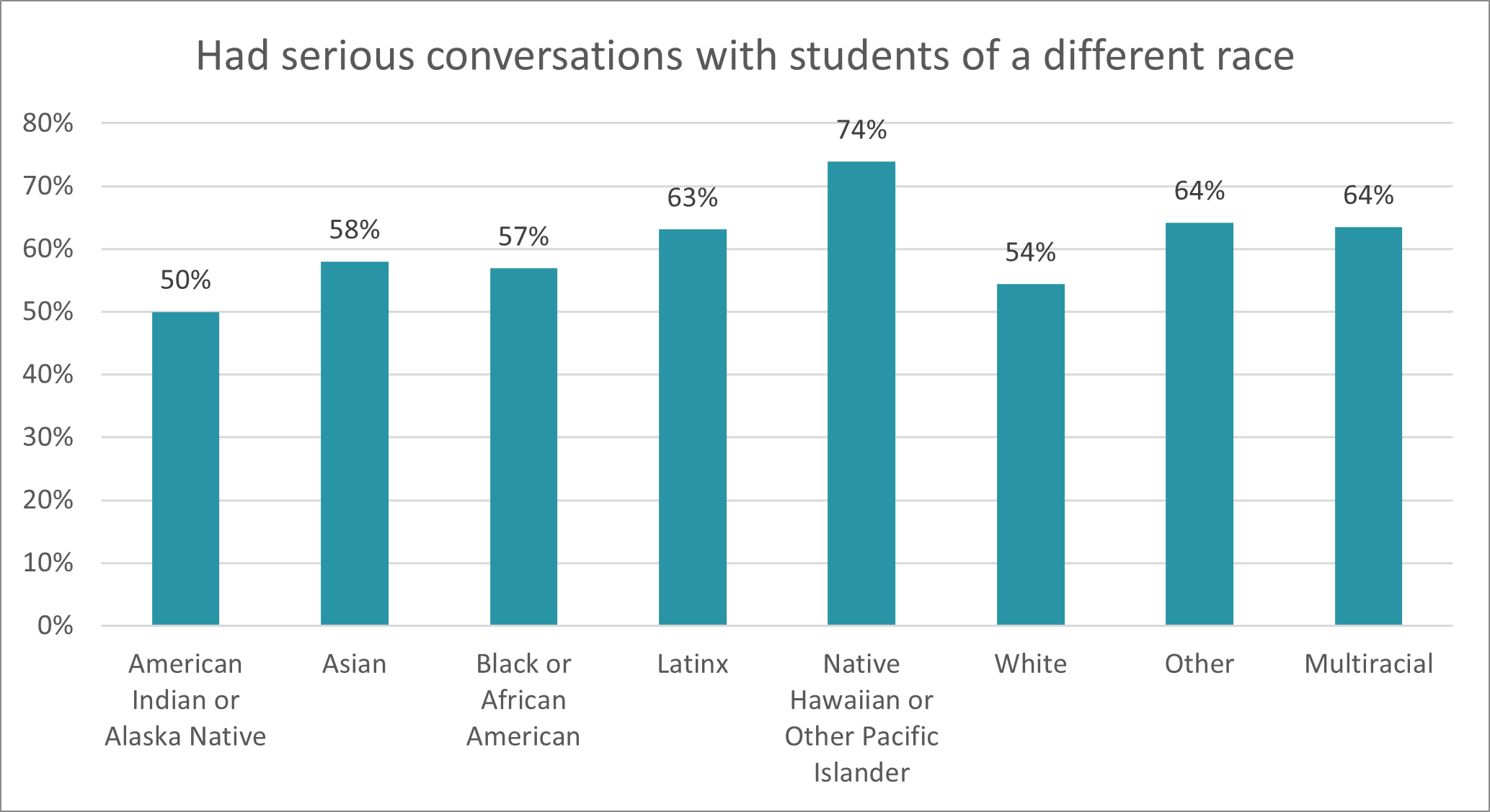

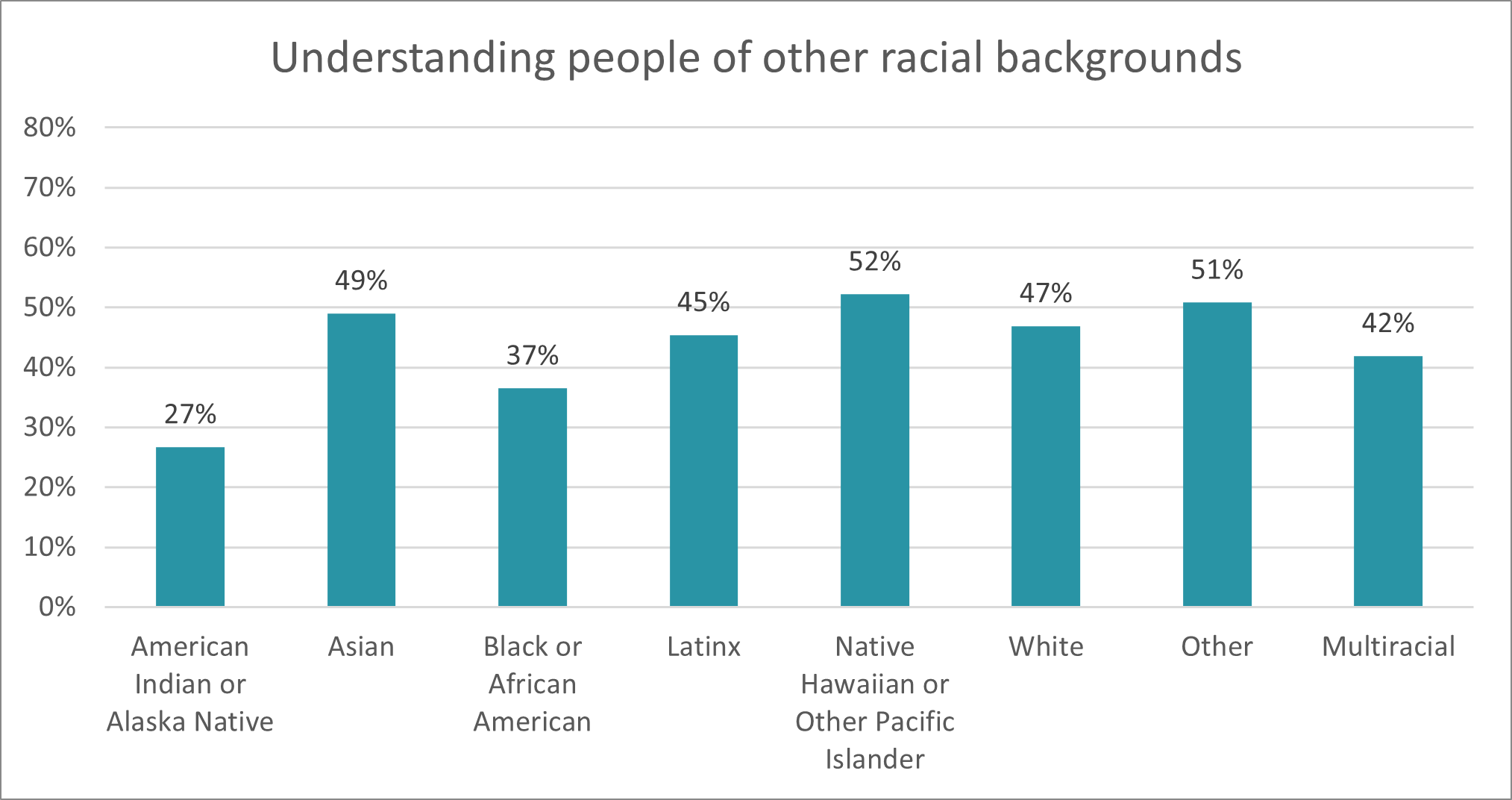

For law students, radical solidarity means working with other groups, showing up for their events, collaborating with others. LSSSE data make clear that law students excel at this already, both having serious conversations with students of a different race and working to understand students from different racial backgrounds.

For law professors, it means mentoring across various communities, perhaps reading across histories and cultures, and comparative research. For lawyers, it means building professional bridges and perhaps doing pro bono work for the communities that need it. Radical solidarity might require humility but not apology. I’m sure that there are many in our communities with very different ideas and politics but I speak here to the majority of us who believe in social equality.

- Embracing excellence and failure

Asians Americans are known as the “model minority.” It’s a pernicious myth about exceptionalism that is used to chastise other minority groups. In the last few years, weaponizing Asian excellence to harm other minority groups has been difficult for most Asians because we support affirmative action. How do we celebrate the very excellence that has been used to falsely exceptionalize us? Others have written extensively about the harms of this myth not only to others but to Asians themselves. Here I want to reflect on another consequence: a reluctance to embrace our successes and excellence as a community because it reinforces the myth.

The model minority myth has led to an ambivalence in celebrating our communities’ successes—an obstacle that few other groups have had to overcome. Achieving success because of hard work should be celebrated for itself while understanding that it says nothing about the value and success of any other group. Our radical solidarity with marginalized groups prevents us from claiming any exceptionalism for ourselves. And celebrating Asian Americans who succeed should not be mistaken for it. Nor should it be denigrated as mere borrowing, assimilationism, or white adjacency which is another kind of negative exceptionalism. Other groups’ similar successes are rarely spoken of in these denigrating ways.

So, celebrate the Indian kids who win spelling bees, the Chinese kid who wins the math competition while rejecting that Asians are somehow exceptional at spelling or math! Our stars are just that: stars. We have exceptional talents who deserve to be celebrated.

I want to end on a positive note on what is commonly thought to be a negative experience: failure. One stereotype about Asians is that, in our families and communities, failure is not an option. However, we should embrace failure as part of success rather than as a shameful shortcoming. As a law professor, I tell my students that they should learn from their failures, admit to them, overcome them, and move forward. Failures are inevitable and learning to cope with them without shame is important to the mental health of the community.[3] Asians fail as much as any other group and to deny this is to enforce an unacceptably high standard. To fully lay the model minority myth at rest, we must accept both our success and our failure. Asian belonging is not contingent on group accomplishment or excellence. We deserve the sunlight, to be visible, and fully accepted as Americans when we’re winning as well as when we’re not.

____

[1] Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard; Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina

[2] Jenny T. Wang, Ph.D., Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans (2023).

[3] See id.