The Power of Critical Legal Research

Priya Baskaran

American University Washington College of Law

Every year students ask me which classes are “the most important” to prepare them for successful and fulfilling legal careers. Should they focus on Bar classes or load up on Business Law for future corporate practice? Or should they opt for a seminar that will really engage their interest in human rights or environmental justice? Inevitably many students seek me out because as a professor at the top ranked clinical program at American University Washington College of Law, I actively engage in the practice of law. I also closely supervise and ultimately grade my clinic students on their own lawyering skills. The students who seek my advice do so because they are keen to acquire the skills and training to lawyer well. My response often surprises students: Take an advanced legal research class and focus on Critical Legal Research.

Legal research is too often conflated with navigating a commercial search database as quickly as possible. In reality, legal research is a complex, dynamic, and iterative process that requires a combination of critical thinking, analysis, strategy, and perseverance. Legal research is also a large part of the average attorney’s work life, particularly early career attorneys.[1] Finally, and most importantly in my mind, developing strong legal research foundations is essential to solving complex, real-world problems. This latter point is only increasing in relevance with the continued growth of generative AI.

Legal research provides students with a primer in intersecting legal regimes, showcasing how various subjects we teach in self-contained classes actually combine and impact the facts of any given case or circumstance.[2] Legal research then teaches students how to critically examine and sort these intersections into tiers of relevance for their various research questions and research tasks. Finally, legal research focuses on creating search plans and strategies. This includes understanding where they find this information – specialized secondary sources, primary authorities practice related resources, even specialized databases. Students also actively analyze and evaluate the results of their searches, making thoughtful and critical determinations when sorting and prioritizing information.[3]

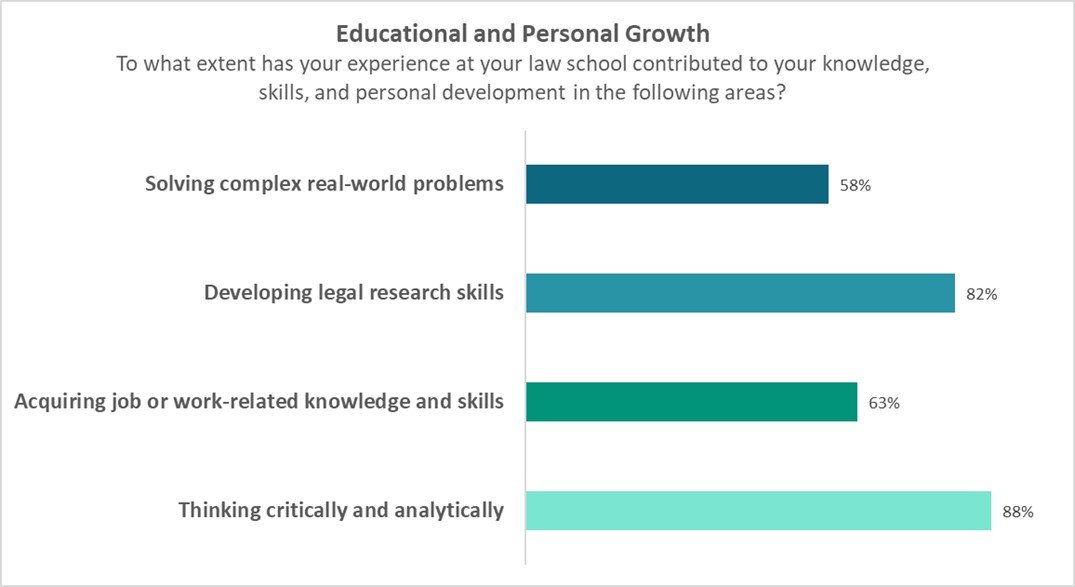

A properly taught legal research class excels in equipping students with the skills essential to good lawyering: 1) complex problem solving by researching messy or novel situations, 2) practical training in a core lawyering skill – legal research, 3) the ability to engage in active learning by directly researching, and 4) developing critical thinking and analysis skills. We see from LSSSE data that a majority of law students do learn these skills in law school.

*Students responding “quite a bit” or “very much”

In particular, a number of schools are increasingly using critical information literacy and Critical Legal Research to teach legal research. Critical legal information literacy is a pedagogy that challenges conceptions of legal research databases as neutral or comprehensive. Instead, critical information literacy teaches students that legal information is intentionally curated and categorized, often for commercial purposes.[4] This teaches students to be careful, thoughtful readers when their search results skew in favor of the status quo. Similarly, Critical Legal Research (CLR) builds on critical legal information literacy and incorporates critical legal theories and methodologies into the legal research process.[5] CLR challenges students to rethink their research questions, research strategies, and develop more expansive and thoughtful research plans in order to account for systemic bias. CLR underscores how the existing commercial search databases can entrench hegemonic interests, harming novel arguments that can advocate for more just outcomes.[6]

Take for example the case of a retail employee in June 2020. The employee works for a popular coffee chain that has been deemed “an essential business” during the COVID-19 epidemic. The employee routinely has to interface with customers who refuse to follow the safety protocols required by the county health department, including masking. Her manager requires employees still serve these customers despite the violation of the county health code and the CDC requirements. The employee finds her current work situation untenable for a number of reasons. First, she is deeply troubled by the request to break county law by violating the health department’s mandate. Second, she is concerned for her safety and the safety of her family (including an immunocompromised dependent). She feels like she has no choice but to quit her job but is worried about qualifying for unemployment insurance benefits.

We can immediately issue spot many complicated legal problems that will arise from this case. We can also identify the person being impacted by these “justice” issues – a worker facing both economic precarity and unsafe working conditions. Finally, we should be able to recognize that legal precedent will be exceedingly thin as June 2020 was still the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Building a case with little to no case law requires creative thinking and creative research strategies. What other sources may prove informative or be persuasive? Are there corollaries we can draw to other illnesses or other jurisdictions we should use to build our argument? Finally, we must identify and discuss that justice – when it goes against the dominant interests – requires creative and tireless advocacy on the part of the attorney.

Moreover, the continued growth of generative AI requires that we are even more thoughtful in training students.[7] A poorly trained student will use generative AI as a crutch, adding minimal to no value and simply regurgitating the algorithms findings. A well-trained researcher will identify the shortcomings of the AI tools, creating a comprehensive search plan and strategy that acknowledges and mitigates these flaws. For example, an AI tool may write a briefing memo summarizing the findings and state that the worker has little precedent and therefore a weak case. A well-trained researcher will be able to understand why this AI argument is insufficient for the client and for greater justice. The researcher may even be able to use this AI answer to play devil’s advocate, building a more creative response to counter the points generated by the status quo algorithm.

There is no shortage of conversation surrounding AI in law schools. In addition to discussing academic integrity and ethics, we must use this moment to explore critical pedagogies. How can we as professors help our students understand the blindspots of commercial AI? How can we train them to become better thinkers, lawyers, and advocates by exposing them to the limitations and injustice implications of both AI and traditional research? The answer may lie in leveraging critical legal information literacy and CLR in our own classes and pedagogies.

Although legal research is often limited to the first year curriculum, there are ample opportunities for instructors to engage with the topic in other courses. My forthcoming article, Searching for Justice: Incorporating Critical Legal Research in Clinic Seminar, includes a bibliography of scholarly work and pedagogical tools created by librarians and experts in the field. Professors can and should scaffold student learning by leveraging Critical Legal Research within their pedagogies, training more thoughtful and critical attorneys.

__

[1] Noting that new attorneys spend an average of one third of their time researching. Steven A. Lastres, Rebooting Legal Research in a Digital Age 3 (2013), https://www.lexis nexis.com/documents/pdf/20130806061418_large.pdf [https://perma.cc/SH5Q-Z2D3].

[2] THE BOULDER STATEMENTS ON LEGAL RESEARCH EDUCATION: THE INTERSECTION OF INTELLECTUAL AND PRACTICAL SKILLS (Susan Nevelow Mart ed., Heinemann, 2014). P. xii.

[3] Sarah Valentine, Legal Research as a Fundamental Skill: A Lifeboat for Students and Law Schools, 39 U. Balt. L. Rev. 173, 201 (2010).

[4] Yasmin Sokkar Harker, Legal Information for Social Justice: The New ACRL Framework and Critical Information Literacy, 2 Legal Info. Rev. 19,43 (2016-2017).

[5] .Nicholas F. Stump, Following New Lights: Critical Legal Research Strategies as a Spark for Law Reform in Appalachia, 23 Am. U. J. Gender Soc. Pol’y & L. 573, 603 (2015); Nicholas Mignanelli, Critical Legal Research: Who Needs It?, 112 LAW LIBR. J. 327 (2020).

[6] Nicholas F. Stump, COVID, Climate Change, and Transformative Social Justice: A Critical Legal Research Approach, 47 WM. & MARY ENVTL. L. & POL’Y REV. 147 (2022).

[7] For a fuller exploration of the intersection between generative and legal research, I recommend reading: Nicholas Mignanelli, Prophets for an Algorithmic Age, 101 B.U. Law Rev. 41, 44 (2021).