Laila L. Harris

Laila L. Harris

Associate Professor of Law & Co-Director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic

Associate Provost of International Affairs

Tulane University Law School

This fall, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory on the mental health and well-being of parents, responding to levels of high stress parents report and the harmful effects on their own mental health, as well as their children’s. This was on the heels of findings from a national study that a majority of parents experience isolation, loneliness and burnout related to parenting. For those of us at law schools, often recognized as high stress environments already, it raises the question: what is the landscape for parents in law schools?

Professor Lindsay M. Harris (University of San Francisco Law School) and I have begun talking and writing about “the parenting professor penalty,” the panoply of harms and challenges that pregnant and parenting people, as well as those who are presumed to become pregnant or parenting, face in entering and being successful as faculty within the legal academy. We are bringing this topic to the annual AALS meeting, focused on “Courage in Action” held in January as a discussion group session and welcome you to join us. Yet faculty often comprise those with the most privileged positions in law schools, relative to staff and students. Law students who are parents, or more broadly caretakers, may face steep challenges and inequities related to their status and circumstances.

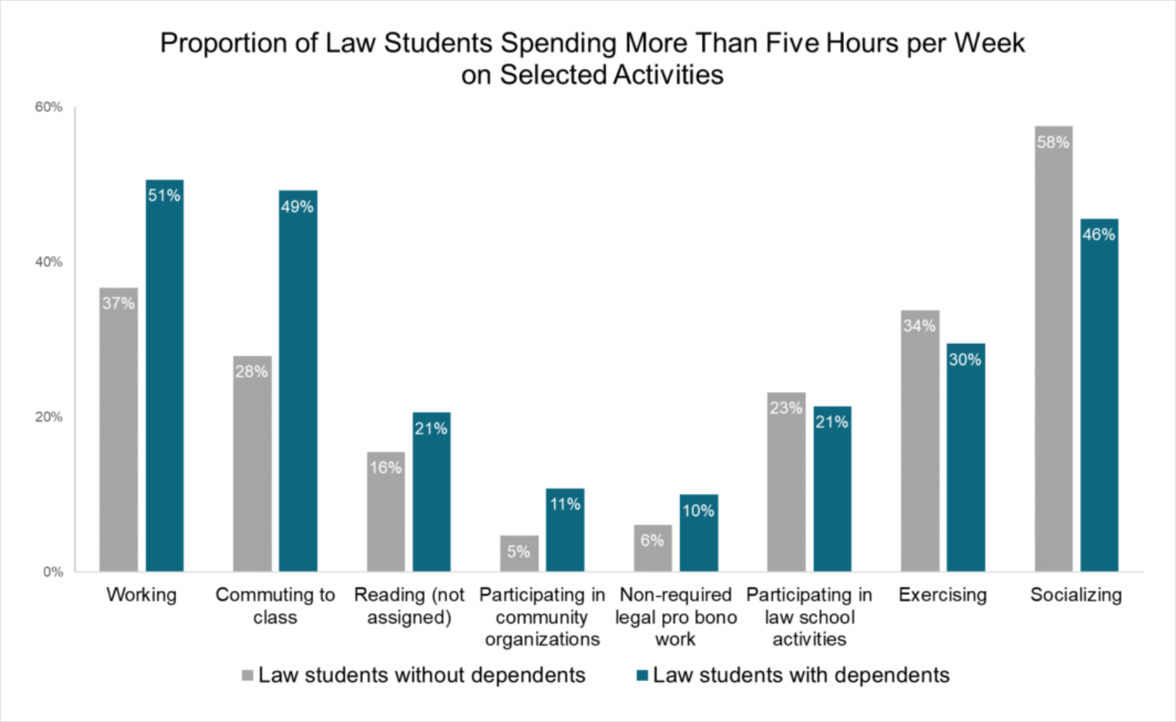

Mental health has long been a concern in law schools and the legal profession. According to LSSSE, around 60% of law students experience very high law-school related stress or anxiety. Law students who also serve as caretakers are particularly likely to have more stress. This is especially true because students with dependents also spend more time on commuting to class and working, and less time on exercising and socializing, which may help combating anxiety and isolation.

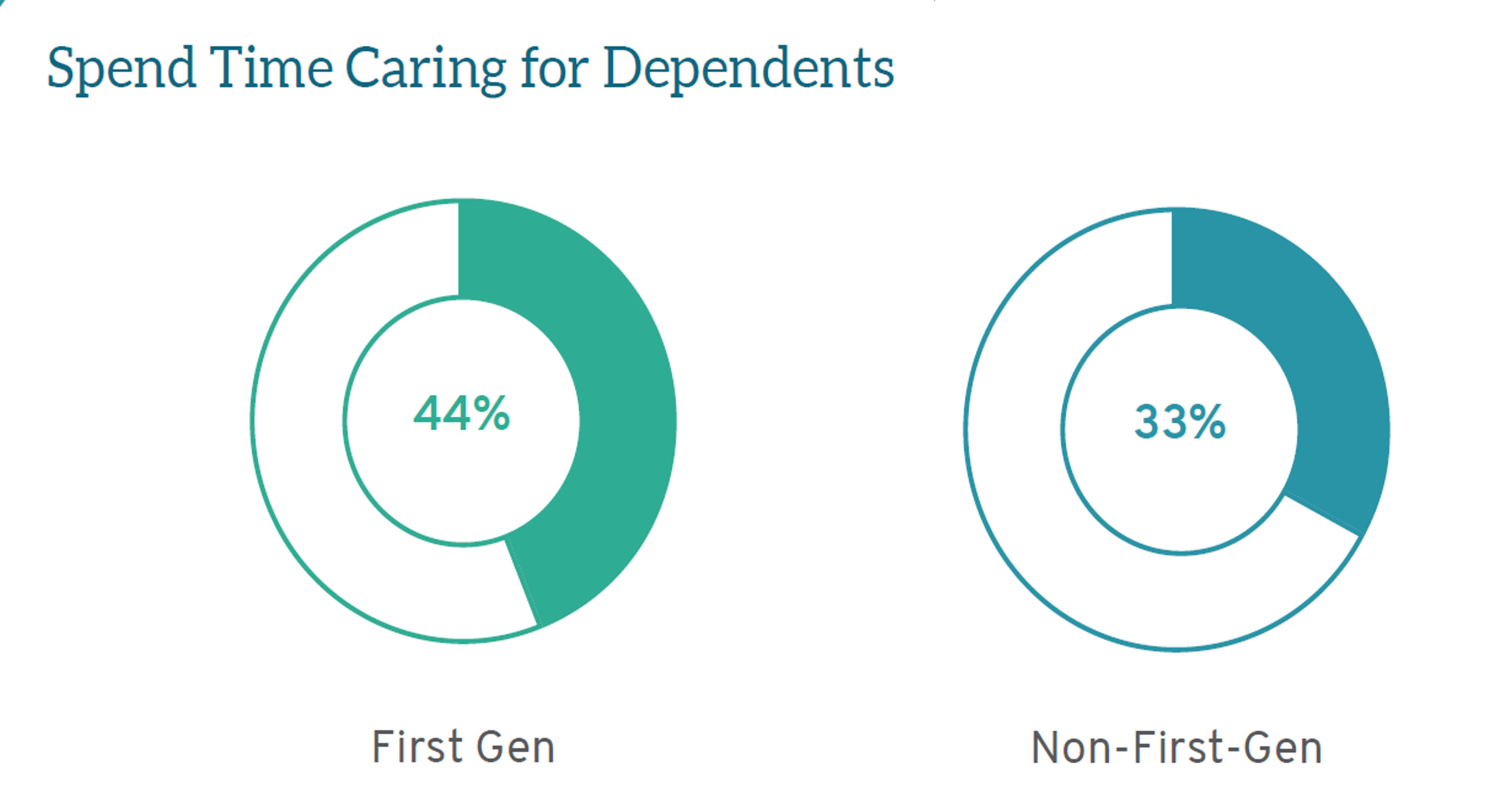

While about one-third of law students reported spending time caring for dependents, the burden of hours spent every week is particularly high for non-traditional law students. First-gen students comprise a larger portion of law student caretakers: 44% of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

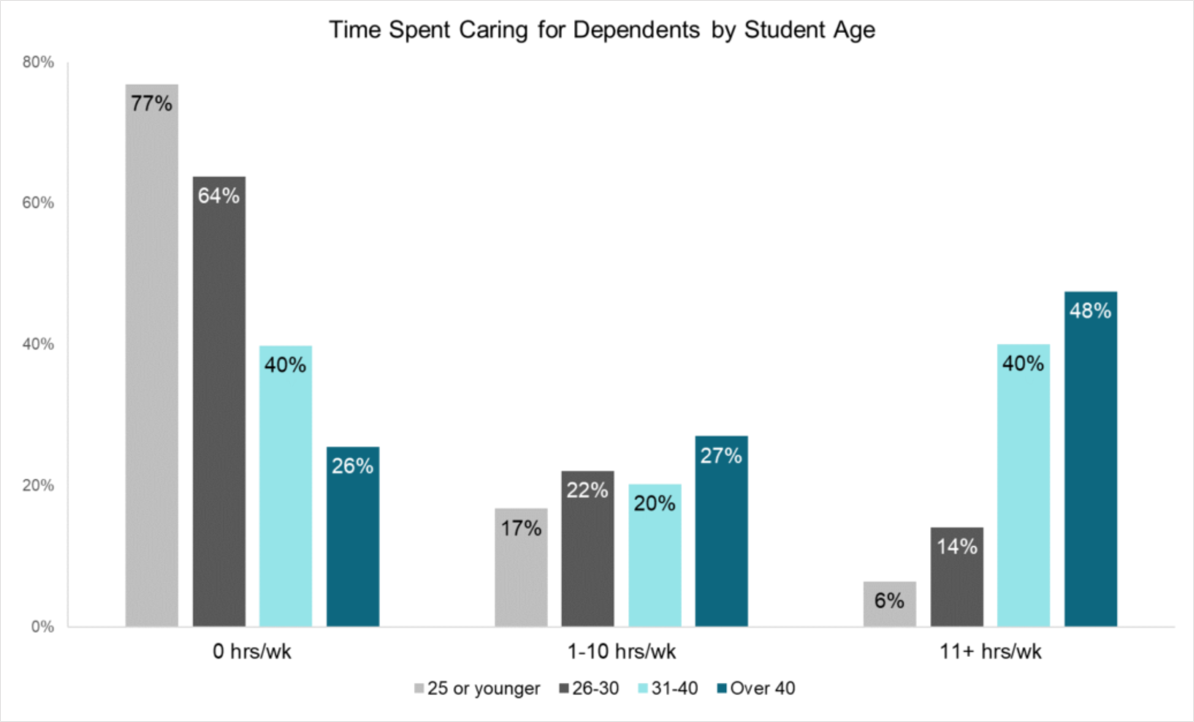

Caretakers are also over-represented in part-time law programs, with 56% of part-time students reporting caretaking for dependents. Time spent caretaking per week is highest for older law students, as 40% of those aged 31-40 spent 11 or more hours per week caretaking, and nearly half of those aged over 40 spent 11 or more hours caring for dependents.

Given these genuine concerns for law student caregivers, how can we as law faculty respond individually and collectively, and how can we respond institutionally as law schools?

As individual actors, law professors should think about how to account for the stresses parenting law students may be facing. Professor Harris and Professor Mallika Kaur recently released a co-edited volume titled How to Account for Trauma and Emotions in Law Teaching, which is instructive and helps to mainstream conversations about stress and well-being within law schools. Professors may, for example, want to think about whether they want to model “parenting loudly,” though this is not without varying consequences depending on an individual professor’s positionality, as Professor Meera E. Deo documents in her book Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia.

How can law schools as institutions respond to the special needs of law students who are caretakers and are at risk of heightened stress and burnout? As part of the ABA mandate that law schools provide substantial opportunities to explore “well-being practices,” law schools should offer meaningful courses and co-curricular activities to address law students’ well-being, including trainings, screenings, and policies to encourage work-life balance. These co-curricular programs should also have resources to address the particular needs of law students who are parents or caretakers. Some institutions do this already. For example, some schools have created a clearinghouse of information directing students to school and city-specific parenting resources, as well as child care subsidies and student groups.

Schools should also conduct internal assessments to learn about the experiences and needs of law students who are caregivers to consider whether policies and practices around leaves and broader resources for this community are responsive to needs. Creative responses including creating parenting support groups are warranted. Schools can also take steps to accommodate the schedules for working parents. For example, one law school designated one of the nine first year small section modules as the parent module (affectionately called the “mommy mod”) and classes were scheduled to align with times when school was open and to accommodate drop off and pick up responsibilities. Similarly, another school designed a part-time law program so law students with school age children take coursework while their children are in school. Finally, as a broader measure and perhaps an impetus for the cultural shift the moment demands, U.S. law schools should consider signing on to the International Guidelines for Wellbeing in Legal Education, which would require a comprehensive overhaul of law school structure, curriculum, and atmosphere with well-being in mind.