Navigating career decisions can be one of the most challenging aspects of law school, and many students find themselves seeking advice to chart their path forward. Whether considering judicial clerkships, corporate law roles, public interest positions, or alternative legal careers, law students often feel a mix of excitement and uncertainty. Balancing academic demands with the pressure to make strategic choices about internships, networking, and future goals requires careful planning. And the guidance of mentors, professors, and peers can make all the difference.

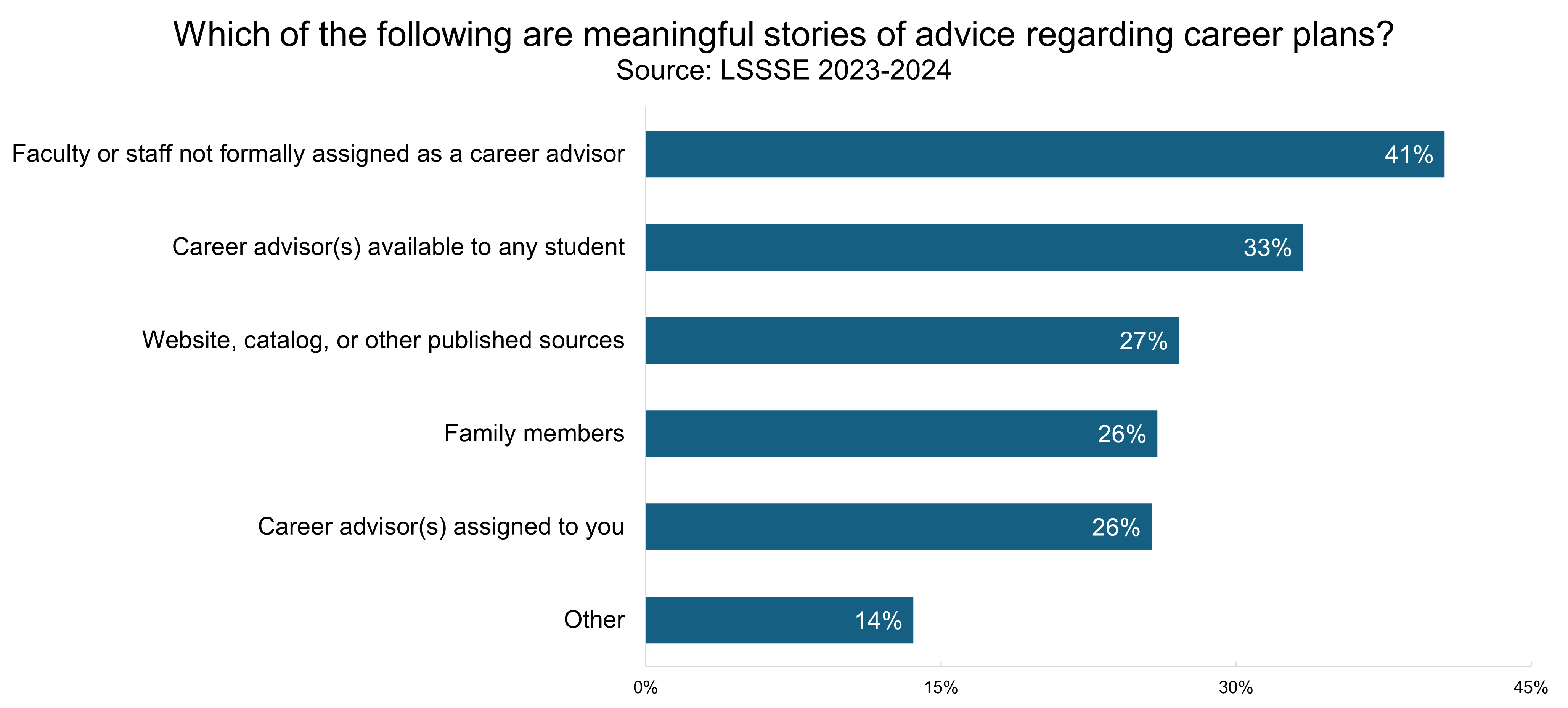

Using 2023-2024 data from the LSSSE Student Services module, we examined the meaningful sources of career advice that law students draw upon to help with professional preparation. Interestingly, law students are more likely to seek out career advice from faculty or staff members not formally assigned as career advisors rather than from formal career advisors at their law school. Only about a third of law students receive meaningful advice from careers advisors available to any student, and only about a quarter receive meaningful advice from a career advisor assigned to them, which is equal to the percentage of students receiving meaningful advice from family members (26%).

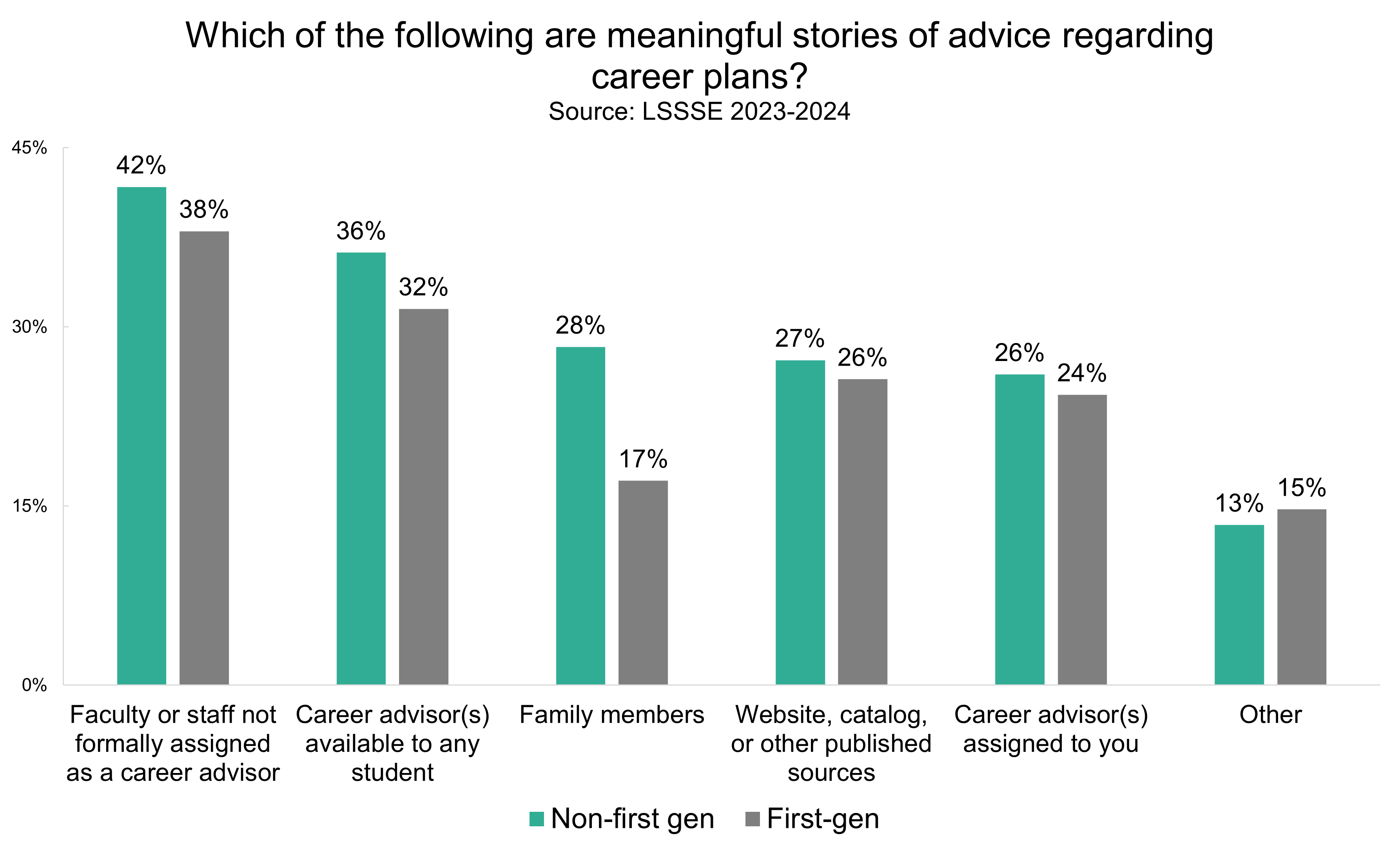

Given that family input will vary widely across different student backgrounds, we compared the sources of career advice for first-generation and non-first-generation law students. For first-generation law students (those who do not have a parent with at least a bachelor’s degree), family members are much less likely to be a meaningful source of career advice. However, troublingly, first-generation students are also less likely to receive meaningful career advice from other sources relative to their non-first-generation peers. In other words, law schools may not be filling the gaps for first-generation students to support their transition into the legal profession.

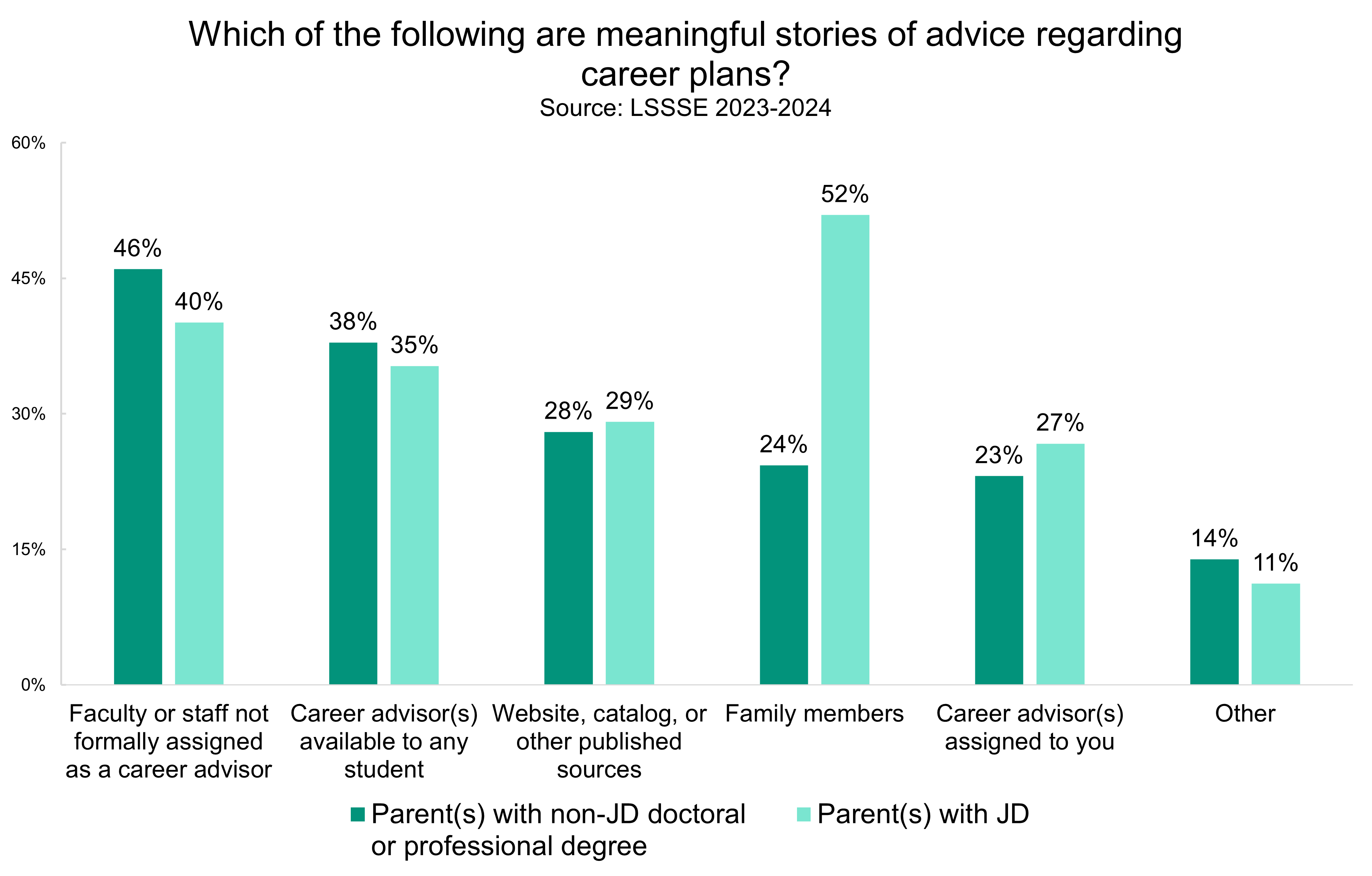

Digging deeper into the non-first-generation data, we wanted to know what impact having a parent with a law degree has on students’ sources of meaningful career advice. Among students who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree, we see, not surprisingly, that students who have a parent with a JD are more likely to cite family members as a meaningful source of career advice than students who have a parent with a non-JD doctoral or professional degree. However, only around half (52%) of law students who have a parent with a JD note that they are receiving meaningful career advice from a family member. The students with a JD-holding parent are a little more likely to get advice from career advisors assigned to them and a little less likely to receive advice from faculty, staff, or career advisors who are not formally assigned to them.

These findings highlight critical gaps and opportunities in how law schools support students in their career preparation. While informal networks and personal relationships with faculty or staff often play a vital role, the data suggest that formal career advising structures may not be as effective as they could be, particularly for first-generation students. Law schools should consider rethinking how they engage with students in career advising, ensuring that resources are accessible and tailored to meet the diverse needs of their student body. By strengthening these systems and bridging the advice gap, particularly for those from underrepresented backgrounds, law schools can better prepare all students for the challenges and opportunities of the legal profession.