Stephen Daniels

Research Professor Emeritus

American Bar Foundation

Shih-Chun Chien

Assistant Professor

Cleveland State University College of Law

Students’ motivations for attending law school and choosing law as a career are crucially important. So we have argued in two previous posts[1] and elsewhere.[2] Those motivations are important for understanding students’ career aspirations and what they hope to do as lawyers. (we have a special interest in public service).[3] More generally they help in understanding the future of the legal profession and the role it plays or should play in our society.

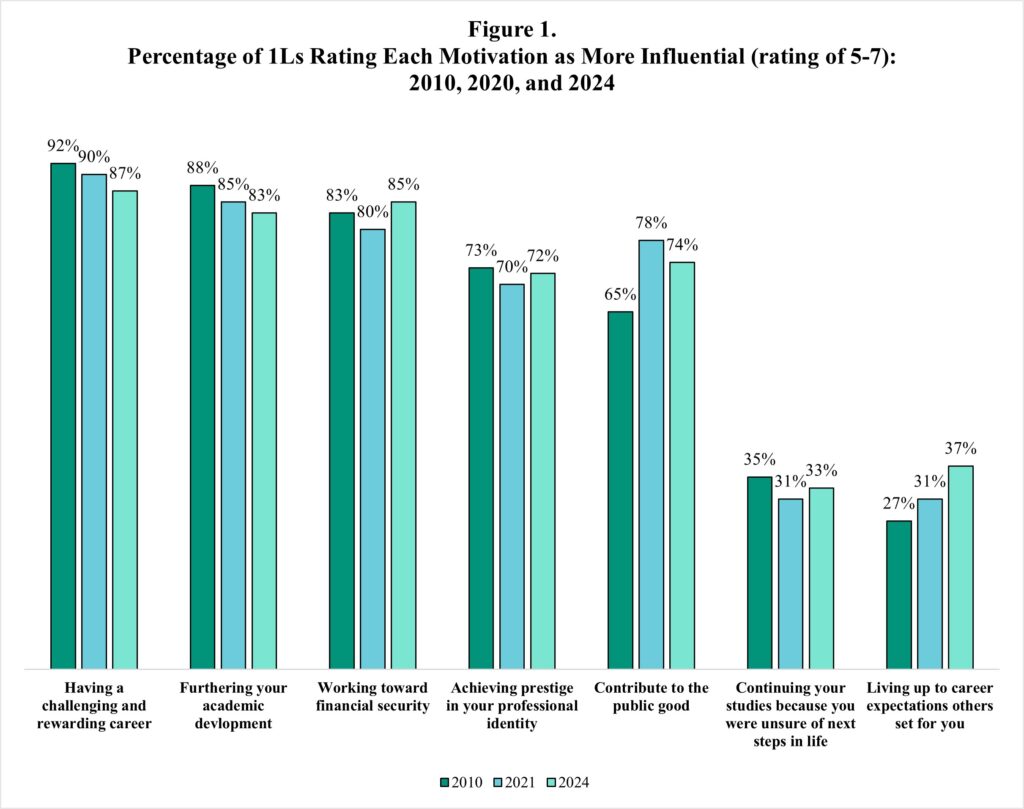

Our exploration of motivations began with a special set of seven questions (in addition to the full suite of annual questions) posed to a subset of the 2010 LSSSE survey schools. The questions asked students to rate each of seven motivations on seven-point scale from “not at all influential” to “very influential” (see Figure 1 below). Importantly, each motivation was assessed independently, meaning students were not asked to choose among them. These questions were the focus of our first post.

Wanting to extend our work we asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions to the 2021 survey. They generously did so adding the questions for a subset of schools. With an interest in any change in responses to the motivation questions, a comparison of the 2010 and 2021 responses to those questions was the focus of our second post.

Working with the null hypothesis of no substantial change in motivations between 2010 and 2021, we found that to be the case with one key exception. It involved the motivation of contributing to the public good, one of importance to us with our interest in public service. It became more important in 2021 compared to 2010. Wondering if this change signaled an ongoing shift or perhaps just a short-term disturbance related to the COVID pandemic, we again asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions for a subset of schools in the 2024 survey. And again, they did.[4]

Here we compare the 2024 motivation responses to those from 2010 and 2021, looking for evidence of an ongoing shift for contributing to the public good or a short-term disturbance.

Drawing from each of the surveys, Figure 1 compares 1L responses to the seven motivation questions. The bars represent the percentage who reported that a given motivation was more influential for them (a rating of 5, 6, or 7 on the seven-point scale). 1Ls because they are closest to the decision to attend law school.

Perhaps the most striking general pattern is the relative stability in 1L motivations. With only small decreases over time in the degree of influence, the intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development are the most intense motivations. They are followed by the extrinsic motivation of financial security, which stayed within a narrow range. A bit lower in intensity is the extrinsic motivation of prestige, that also stayed within a narrow range.

Perhaps the most striking general pattern is the relative stability in 1L motivations. With only small decreases over time in the degree of influence, the intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development are the most intense motivations. They are followed by the extrinsic motivation of financial security, which stayed within a narrow range. A bit lower in intensity is the extrinsic motivation of prestige, that also stayed within a narrow range.

The extrinsic motivation of contributing to the public good is different, with a marked increase from 2010 to 2021 in its importance. The question for us is whether this was just a short-term disturbance. While there is a small decrease in 2024 (not unlike those for challenging career and academic development), the percentage does not return to the 2010 level. The importance of this is a focus of our ongoing analyses.

Perhaps we can say these five motivations make-up a relatively stable core (relative only because of the shifts for public good) for most students, one reflecting the mixture of motivations – intrinsic and extrinsic — drawing students to law school. The remaining two motivations – unsure and others – are less important in comparison, but not unimportant. They are different in not having an identifiable substance as the others do and pose an interesting interpretative challenge.

Importantly, even at the individual-level students report a mixture of motivations – particular motivations are not necessarily mutually exclusive (again, each motivation was assessed independently). A simple correlation matrix using he 2024 data – which shows the relationships each of the motivations has with each of the other motivations – shows few relationships that are not significant.[5]

Not every law school appears in each annual LSSSE survey or in the motivation subsets, but one school did appear in each of the motivation subsets. Like the general pattern in Figure 1, it had a marked increase in the importance of the public good motivation between 2010 and 2021 (more influential going from 63% to 77%), with a slight decrease in 2024 (more influential 75%). A second school appeared in 2010 and 2024, with more influential at 66% in 2010 and at 73% in 2024. What we don’t know is whether some schools may be more attractive to those motivated by the public good and others less so.

The extent to which motivations and aspirations are connected is the focus of our ongoing work along with the ways law schools can support public service careers. While not all who are motivated by the public good will go into public service, it is still important to know if the interest in the public good follows students into other legal careers as well. Fostering this motivation should be a part of any idea of professional identity.

___

[1] Stephen Daniels and Shih-Chun Chien,” Beyond Enrollment: Why Motivations Matter to the Study of Legal Education and the Legal Profession?” LSSSE Guest Blog (Sept. 24, 2020); Stephen Daniels and Shih-Chun Chien, “Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now” (Dec. 21, 2021).

[2] Shih-Chun Chien and Stephen Daniels, Who Wants to be a Prosecutor? And Why Care? Law Students’ Career Aspirations and Reform Prosecutors’ Goals, 65 HOWARD L.J. 173 (2021).

[3] While we are interested in public service generally, we have a special interest in the criminal justice system (e.g., as prosecutors and public defenders).

[4] The respective motivation subsets were not the same for each survey (2010, 2021, and 2024). Perhaps we can look at the subsets as a very rough form of sampling with replacement from a relatively small population.

[5] The relationship between public good and financial security is not significant as is the relationship between public good and unsure and public good and others’ expectations. Of course, not all relationships are strong or even positive.