Guest Post: Legal Education and the Illusion of Inclusion

Guest Post: Legal Education and the Illusion of Inclusion

Shaun Ossei-Owusu

Shaun Ossei-Owusu

Presidential Assistant Professor of Law

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School

A new semester and a potentially new political landscape are upon us. Last month law students around the country resumed coursework. Their educational pursuits are virtual, in-person, or some mix of both. No matter the format, law students continue their educational journey in an ideologically polarized pandemic society where race, class, and gender disparities are on sharp display.

Students will also be learning in a context where changes in our legal system may have direct relevance to their legal education. As is typically the case, a newly constituted Supreme Court has a diverse docket this term that might shape substantive areas of law that students take courses in, chiefly constitutional law. There will be regulatory shifts that come with new administrations. These kinds of changes will have meaning for administrative law and related areas of law: health law, environmental law, employment law, and civil rights, to name a few. COVID-19 has upended state and federal judiciary systems in ways that have still-undetermined implications for procedural courses law students take (e.g., evidence, civil procedure, criminal procedure) and access to justice issues more generally. And we know from the late Deborah Rhode’s work which communities access to justice issues tend to devastate—racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations.

Notwithstanding future uncertainty, one thing can be said with some measure of confidence: issues of race and gender—amongst other social categories—will remain relevant inside and outside the sometimes intellectually-cordoned off walls of law schools. How these issues are integrated in the classroom, if they are at all, will affect the substantive learning of law and will either include or exclude historically marginalized groups.

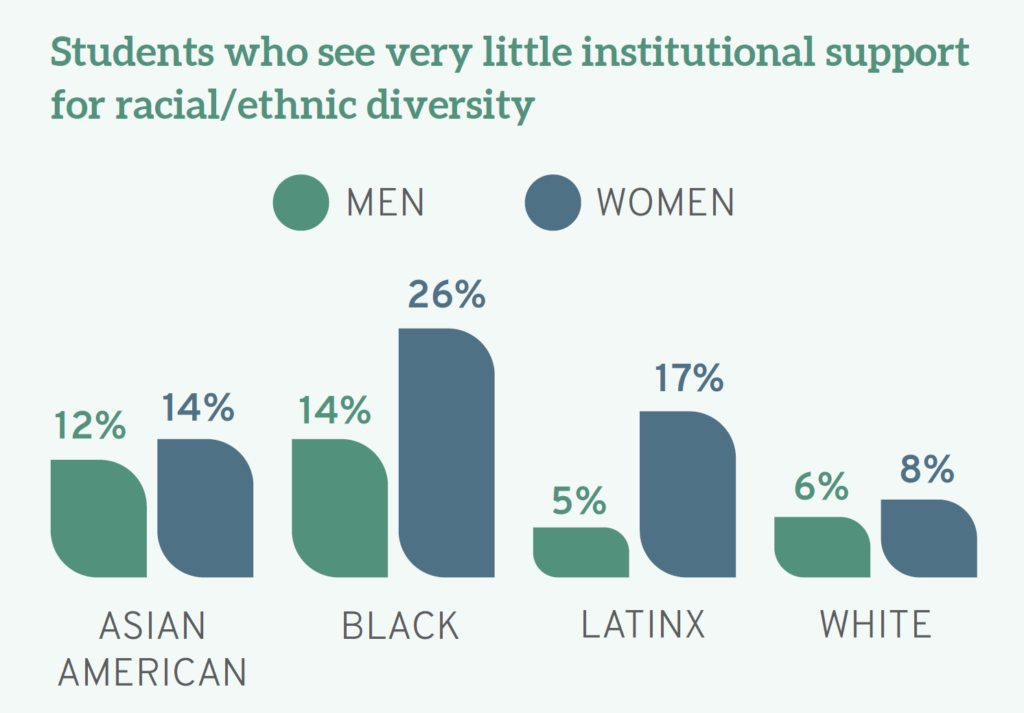

In the specific context of legal education, the results of Law School Survey of Student Engagement’s (LSSSE) Annual Survey illuminate. The Report provides a glimpse into how law schools fail to meet the aspirational goal of inclusion that often takes up primetime real estate on their websites and promotional materials. From my own read, the most jaw-dropping finding is intersectional in nature and about Black and Latinx women law students—aspiring attorneys who are often told that they do not look like lawyers when they transition to practice. 26% of Black women respondents and 17% of Latinx women respondents reported that their schools do “very little” to support racial and ethnic diversity.

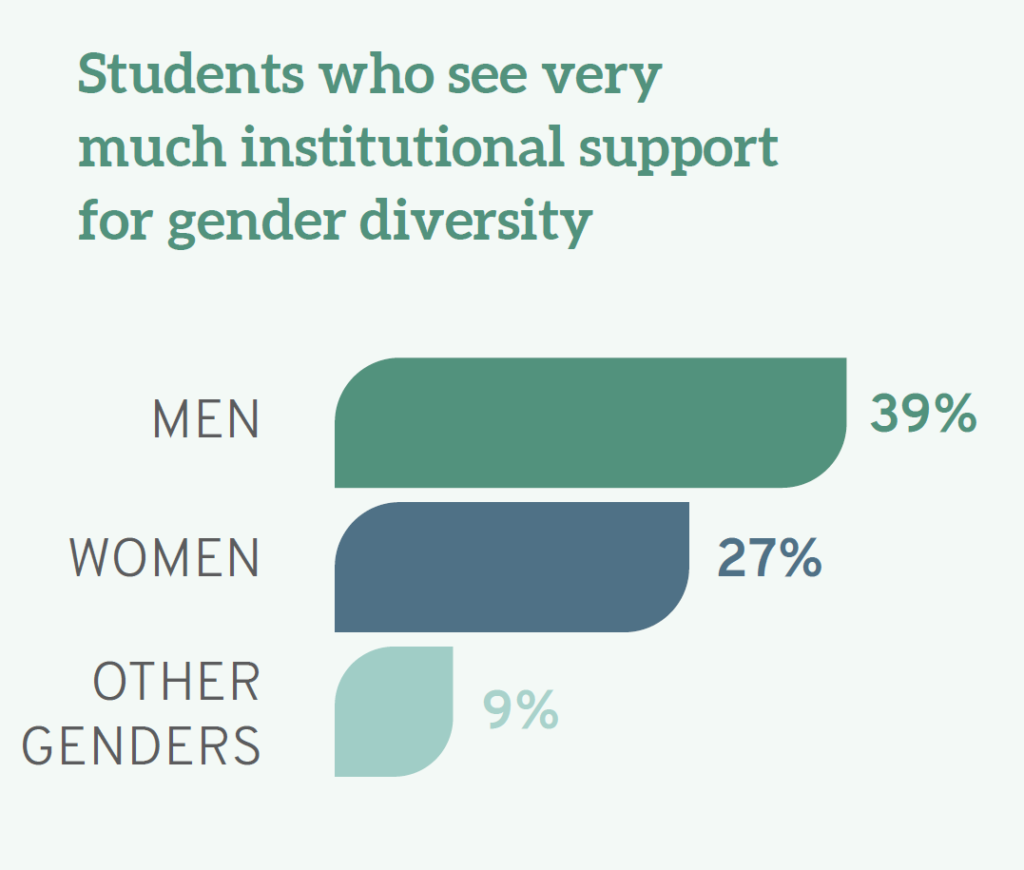

Disenchantment with the lack of support for diversity can be distilled even further. The Report notes that men varied on the issue of gender inclusivity, with 39% “very much” believing that their schools support gender diversity compared to 27% of women and 9% of individuals who identified with the “other gender” category.

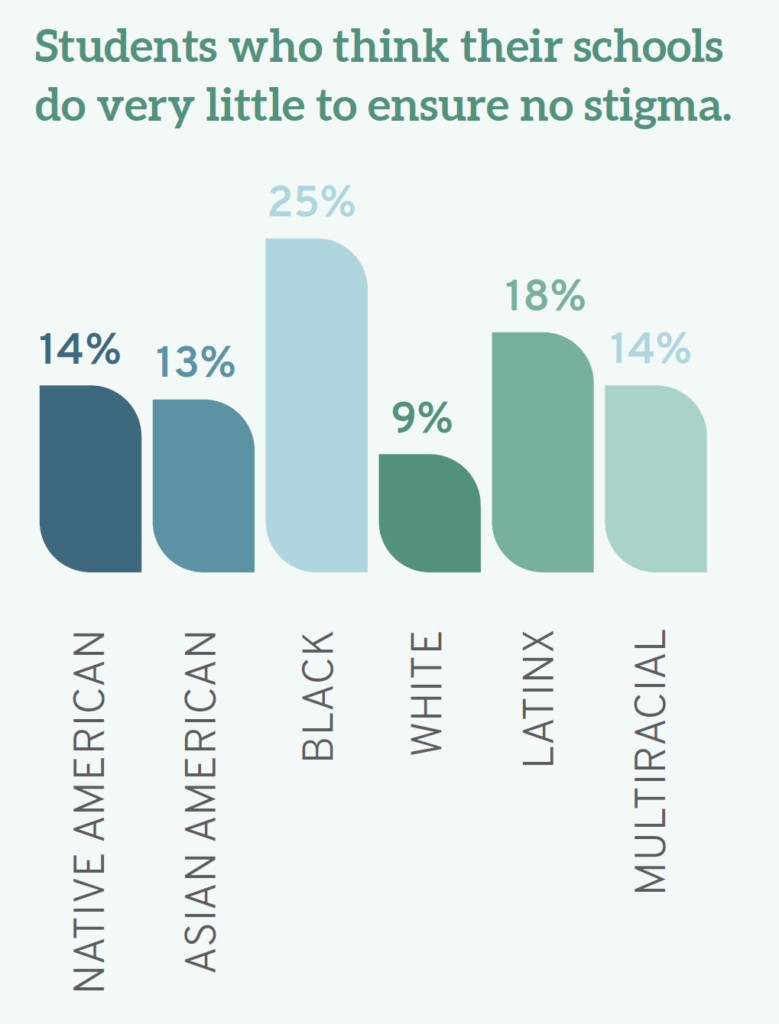

In the context of race, student views also differed, with 9% of White students, 14% of Native American students, 18% of Latinx students, and 25% of Black students believing that their schools do “very little” to ensure that students are not stigmatized based on identity.

Where sexuality and sexual orientation are concerned, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only “very little” to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbian students, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing “very little” in this regard. What do these findings mean for legal education and the political moment I gestured to in the beginning?

LSSSE’s data suggest that some students are dissatisfied with the six-figure education they are receiving. Put plainly, law students from backgrounds that the profession has historically excluded—women, racial minorities, LGBTQ communities, and people with disabilities in particular—do not feel part of the academic community and believe law schools are relatively disinterested in their stigmatization. In some ways, this is unsurprising, as there is a deep scholarly literature and genre of books on student disappointment with law school. Moreover, student disenchantment with legal education—which has a history of exclusion that traces back to the nativism and anti-Semitism of the early twentieth century—may in some ways be pre-determined.

The confines of the classroom, which is one of the many areas the LSSSE survey discusses, provides more insight into the inclusion-exclusion dyad. From the vantage point of some educators, law school is simply about training people to be lawyers. The most generous reading of this position suggests that social justice-like ideas like “inclusion” are too ideologically weighty to meaningfully bring in the classroom. For people who subscribe to this view, attempts at inclusion can create impossible-to-navigate landmines for professors. More skeptically, some see inclusion as an ancillary. Read in this light, the primary goal is to inculcate legal knowledge. For these professors, some things are not relevant to the practice of law and are therefore not relevant to legal education.

Such professional school-based views of legal education, vary in their reasonableness, but are held by swaths of the professoriate. Yet, there is a two-fold problem, and this is where the LSSSE survey is especially useful. First, this vision of legal education rubs up quite abrasively against the representations of law schools as bastions of inclusion. Second, this version of education, in some ways, undermines the well-touted “diversity rationale” in affirmative action jurisprudence. What does diversity mean when the subjects of diversity feel alienated?

Considering the mismatch between some students’ experiences and the stricter professional school model of legal education that some professors are beholden to, there are some options. Educators can simply be more intellectually honest about the reality that law school is a site of professionalization where inclusion principles can be trivialized. Alternatively, law schools can continue to disingenuously hitch the law school wagon to social justice rhetoric while failing to actualize inclusion as a practice. Or, in the most courageous and imaginative versions of themselves, law schools can refashion their curriculum and use developments in the legal world as opportunities to offer more inclusive learning environments.

For law schools committed to the third way, resources abound. Complaints about the need to diversify the content of law school courses have existed for decades. Scholars such as Derrick Bell and Dorothy Brown have authored casebooks that describe how race intersects with different areas of the legal curriculum, whereas feminist legal theorists, poverty researchers, scholars of law and sexuality have penned their own books, supplements, and articles that all give educational guidance on how to bring these issues into core courses, and do so in ways that are doctrinally sound. Still, some professors—many of whom have the most analytically sharp minds on their university campuses—throw their hands up in despair or continue with the same regularly scheduled program. For some of these instructors, these conversations were absent in their legal education, and they were likely not trained to incorporate these issues. Some may think it would be better to leave this work of thematic inclusion to their more expert colleagues (e.g., scholars of race, sex, class, disability) rather than wade into territory where they are sure to mess up. But throwing one's hands up in despair is increasingly a less credible course of action. The pandemic, along with the protests of 2020, have forced some people to rethink how they deliver course content, and more importantly, have made inequality a more prominent theme in our public discourse. The current socio-political moment, and the reality of pandemic pedagogy, call for curricular redesign.

Fortunately, the tools to make the classroom more inclusive are available and they are not limited to the usual courses. To be sure, law professors have written about how first-year courses like criminal law and property are inattentive to inequality in ways that produce the responses found in the LSSSE survey and have offered suggestions on how those same courses could easily be improved. But attempts to diversify and create a more inclusive curriculum are not confined to these foreseeable areas of law but can be found in more unsuspecting places like evidence, corporate law, trust and estates, and intellectual property, to name a few.

Law professors have also identified space in the curriculum for trans-substantive engagement with the kinds of questions and perspectives that demonstrate an awareness of inequality, both in legal education and in law more generally. Indeed, I, along with my colleague Karen Tani, have taken on the task of trying to simultaneously create an inclusive learning environment that rigorously addresses inequality by creating a 50-person Law and Inequality course at Penn Law. This endeavor and more meaningful engagements with diversity need not be limited to women, racial minorities, and sexual minorities. Inclusion also implicates and has meaning for the larger law student population. One of the most understated findings in the LSSSE Report is that 16 percent of white students believed law schools placed “very little” emphasis on issues of equity and privilege and do not prioritize providing students with the skills necessary to confront discrimination and harassment.

My purpose here is not to proselytize teaching a course like the one we are offering. Instead, I want to highlight how student dissatisfaction with inclusion, which the Report highlights in detailed and accessible fashion, can be situated within this critical juncture. 2021 is a unique moment where law schools can reimagine legal education in real time, and for a post-pandemic world. This will not be easy, as this is a stressful time for faculty—some of whom are in high-risk groups during the pandemic and/or have a variety of care obligations. COVID-19 has upended a lot of assumptions and forced people to change longstanding pedagogical practices. Institutions could do a lot of good by encouraging faculty reflection and supporting creative reorganization of current courses.

The LSSSE Report tells us that in many ways, law schools are failing to provide the inclusive educational spaces that they, I believe in good faith, want to offer and that students of various backgrounds actively desire. Ultimately, the teaching tools are available, the moment is ripe, and the only outstanding question is whether legal educators will make the changes necessary so that the next LSSSE survey offers more optimistic findings.

Guest Post: Connections and Community in Distanced Classrooms

Guest Post: Connections and Community in Distanced Classrooms

Jessica Erickson

Jessica Erickson

Professor & Associate Dean for Faculty Development

University of Richmond School of Law

Law faculty put significant thought into designing courses. We draft learning objectives, carefully craft assessments, and consider how to engage students inside and outside of the classroom. When law school courses suddenly moved online, many faculty had to think about a new aspect of course design how to build connections in classrooms where students were remote. Even in classes that were able to meet in-person, many of us found it difficult to develop a classroom community when students were in masks and seated six feet apart.

When we could no longer have casual conversations with students after class or in the hallways, many of us realized just how crucial these connections are for our students and for us. In this blog post, I discuss the importance of relationships to student learning and outcomes, as well as how to develop these relationships in online, hybrid, or physically distanced classes.

- The Importance of Relationships

Connections and community are essential to student learning. As I have previously discussed, research from undergraduate institutions shows that a sense of community is associated with increased motivation, greater enjoyment of classes, and more effective learning. Crucially, data from the Law Student Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) shows that these connections matter to law students as well. LSSSE data has been used to examine both the inputs and outputs of law students’ sense of belonging. Using LSSSE data, we can gain insight into what causes law students to feel a sense of belonging (inputs) and the impact that a sense of belonging has on law students’ performance in law school and their career (outputs).

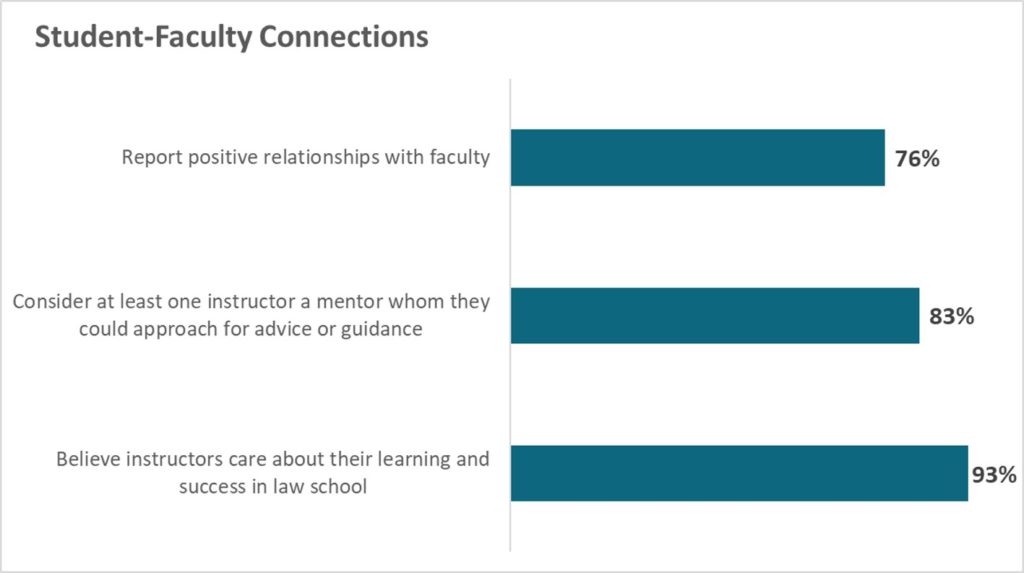

Starting with inputs, LSSSE’s 2018 report Relationships Matter surveyed more than 18,000 students at 72 law schools. The report concludes: “Relationships with faculty, administrators, and peers are among the most influential aspects of the law student experience. These connections deepen students’ sense of belonging and enhance their understanding of class work and the profession.” Connections, in other words, are key when it comes to fostering law students’ sense of belonging. Law schools are doing a good job at developing connections, with 83% of students stating that they have at least one faculty member whom they could approach for advice or guidance.

When it comes to outputs, we can look at research by Professor Victor D. Quintanilla using LSSSE data. He found that a sense of belonging significantly predicted three key outputs – (1) students’ overall experience in law school, (2) whether they would choose to go to law school again, and (3) their academic success (i.e., law school GPA). Moreover, not only does a student’s sense of belonging predict academic performance, but the impact was even greater than other commonly used predictors such as undergraduate GPA and LSAT scores. This means that, even if students come to law school with different academic backgrounds, we can help close this gap by fostering our students’ sense of belonging.

Unfortunately, the research also suggests that building this sense of community is much harder in online or hybrid courses, which most of us who taught this past fall can probably confirm. Now we need to think even more deliberately about how to develop these connections in our classes.

- Building Relationships in Remote or Physically Distanced Classrooms

This past summer, I wrote two blog posts, one with suggestions on how faculty can connect with students in these new learning environments and the other with suggestions on how faculty can help students connect with each other. In this post, I want to reflect back on these strategies now that I have tried many of them with my own students.

First, I found office hours to be a key way to connect with students. I renamed my office hours “student hours” on the advice of a colleague, and I borrowed language from this same colleague to include in my syllabus: “I call these ‘student hours’ for a reason: they are for you. You should come to these student hours if you have a question about the course, but you can also just stop by to introduce yourself, ask any other questions, or talk about your law school experience. I want to get to know you!” At the start of each meeting, I talked with students about how law school was going, and it was a great opportunity to get to know them better.

I call these ‘student hours’ for a reason: they are for you. You should come to these student hours if you have a question about the course, but you can also just stop by to introduce yourself, ask any other questions, or talk about your law school experience. I want to get to know you!

Second, I used technology to connect with students individually. I asked each of my students to create their own Google Doc and share it with me, and they were required to compete short pre-class assignments in their Google Docs. I’ve used this strategy in the past, and found it to be a great way to make sure that students understand the reading. This semester, though, I set aside 1-2 hours before each class to include personal comments on each students’ assignments. I had 52 students across two classes, so it took a while, but it allowed us to connect more personally. I also gave them “Just for Fun” optional questions to include in their Google Doc where they could tell me their favorite board game or share a picture of their pet. I featured a few at the start of class, which was a fun way to personalize a class full of masked students. You can read more about my pre-class assignments here.

Third, several of my colleagues set up individual and small-group meetings with students. One colleague held individual “office hours” with each student. Another who taught a hybrid class met separately with all of her students who were fully remote. A third held online coffee breaks with 3-4 students at a time where the only rule was that they could not talk about course material.

Fourth, optional events allowed me to connect with students in a more relaxed way. In class, I was often preoccupied with the day’s material and all of the tech challenges of my hybrid classroom. In optional events, however, we could talk and connect in a lower-stakes way. I held an optional discussion about a Supreme Court oral argument. I also held review sessions and a Civil Procedure game night where students competed in an online kahoot! If you’ve never tried a kahoot!, I strongly recommend it. It was a great way to let students test their knowledge and have fun at the same time.

Finally, I created opportunities for students to connect with each other. Many faculty were not sure whether students could work in groups six feet apart and wearing masks. It turns out that students can work together pretty easily even under these circumstances. Although it was tempting to incorporate more individualized assessments to keep students separated, it’s important to give them opportunities to deepen their learning with each other. I sometimes felt like a middle school dance chaperone reminding students to stay an appropriate distance apart, but it was worth it.

The final thing I will add is that we need to be careful that our efforts to connect with students do not overwhelm them or us. It is tempting for these community-building exercises to be added on top of what we already ask our students to do in our courses. Now that we have some experience in these new classroom settings, we can be a bit more selective in what we choose to include and assess whether we need to scale back in other areas. At the end of the day, though, as LSSSE data has shown us, relationships matter, and we need to think about how to cultivate these relationships even in these unusual times.

Guest Post: Issue (Blind)Spotting: Using Data to Understand Candidate Motivations to Attend Law School

Guest Post: Issue (Blind)Spotting: Using Data to Understand Candidate Motivations to Attend Law School

Kristin Theis-Alvarez

Kristin Theis-Alvarez

Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid

Berkeley Law

Law school trains students to “issue-spot.” This means faculty test whether students can apply general knowledge to novel situations. The approach mimics the day-to-day practice of law: a client walks through the front door and you weave together their particular issue with your understanding of the applicable law in general. This isn’t unlike what admissions office representatives do when presenting to or advising prospective applicants. I’ve been in law school admissions since 2007, and have communicated with countless candidates, read thousands of applications, and partnered with a wide range of organizations that seek to increase access to legal education – so I have some sense of what applicants are asking. Against that backdrop (what admissions professionals believe is generally true about people interested in law school), our role is to offer advice based on specific candidate concerns. Where do we gain that broader understanding? LSSSE survey data is a good place to start if we want to move beyond anecdotal evidence. It can inform our understanding of candidate motivations for pursuing a law degree which then refines our outreach and recruitment messaging.

For example, through LSSSE data we learn that most students cite a desire to have a challenging and rewarding career as the most influential factor in their decision to enter law school. Over three-quarters of respondents indicated this was their primary motivation for seeking a law degree. So, it’s reasonable to suppose that when speaking to a room of prospective applicants, admissions professionals ought to emphasize career opportunities and employment outcomes. We might focus that message to highlight our school’s unique attributes (placing more emphasis on the percentage of our graduates working in public interest law or the number with federal clerkships, for example), but we’re always speaking to that core motivation.

Another significant motivator for law school attendance is the extent to which earning a law degree can lead not just to a rewarding career, but a lucrative one. LSSSE data tell us that many law students are pursuing the degree based on a desire to work toward greater financial stability. Taken together, the ability to get a job – and for that job to be one that provides financial stability – largely informs the decision to attend law school. This leads admissions professionals to frequently reference our school’s median starting salaries, and partially explains why we emphasize a ‘return on investment’ model to justify the cost of the degree.

LSSSE data also suggest that a desire to further one’s own personal academic development is a significant motivator for law school attendance. As a result, admissions professionals might emphasize our school’s leading programs, commitment to experiential education, research centers, and interdisciplinary education opportunities. We explain that law school is one of the few graduate programs where the strong possibility of professional and financial success intersects with that of individual growth. (More people might pursue a PhD in Classics if the academic job market looked different, and we might have fewer law students if instead of teaching through the casebook method we just handed everyone a list of rules to memorize.) We balance employment statistics with anecdotes about student skills being developed and deployed.

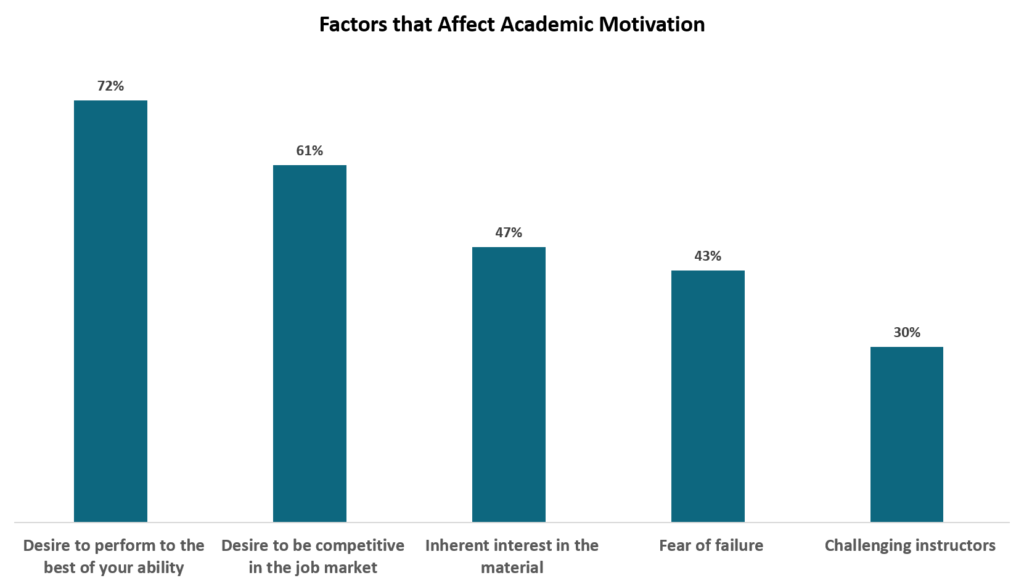

At the same time, less than half of LSSSE respondents report that an “inherent interest” in the curriculum or material they are learning is a source of motivation for them to work hard in law school. This may be why most law admissions professionals are not talking to eager undergraduate students about provisional remedies. It’s also why we generally explain a legal education as the opportunity to develop a diverse toolkit that can be used to solve complex problems, and not merely a content delivery method. Instead, more than half of respondents cite being competitive in the job market as a primary motivation to work hard in law school.

However, there are assumptions that admissions professionals might make when deploying student experience data in our work. Are we asking who we mean when we say “law students,” and who we imagine when we picture “prospective applicants”? More importantly, how do those assumptions lead to missed opportunities to reach candidates from backgrounds underrepresented in the applicant pool?

One way to illustrate this is to examine the differences between general LSSSE data about motivations for attending law school and what we know about the motivations for particular groups. Within the National Native American Bar Association (NNABA) Report “The Pursuit of Inclusion: An In-Depth Exploration of the Experiences and Perspectives of Native American Attorneys in the Legal Profession,” there is a section on the pipeline to law school and the legal profession with a forward written by Stacy Leeds, Dean Emeritus and Professor of Law at the University of Arkansas. This section of the NNABA Report indicates that Native American attorneys were more motivated to enter law school in order to give back to their tribe or Nation, to fight for justice for Indians, and to fight for the betterment of Native peoples’ lives, and less motivated by personal or financial benefit. The data suggest that Native American attorneys’ motivation for attending law school is more connected to identity and heritage, and less tied to individual benefit. According to the NNABA Report, “The difference in why many Native Americans may go to law school is fundamental to understanding how to inspire and motivate more Native Americans to consider law school and the legal profession.” Therefore, not talking to Native American candidates about how to leverage a legal education to serve Native peoples is a missed opportunity to build or fortify interest in the degree.

LSSSE survey data can and should inform a law school admissions office’s outreach and recruitment efforts, but aggregate data can’t be the end of the inquiry. Even within LSSSE data lies the opportunity to further disaggregate, dig deeper, and challenge our assumptions. Admissions professional making use of quantitative data must intentionally work to avoid participation in, or replication of, what Professor Victoria Sutton termed the “paper genocide” of Native American students. And as the NNABA data demonstrates, it’s not safe to assume that what’s true for most is true, or even relevant, for all. Furthermore, the 2020 LSSSE Annual Report “Diversity & Exclusion” shows that the contours of these distinctions persist during (and may even be amplified by) the law school experience itself. Law admissions professionals should therefore question our assumptions about the audiences we speak to, and the students we speak about. Like good lawyers, we must hold general information in the back of our minds, but also listen carefully, research meticulously, and make adjustments. Spotting that issue will not only make admissions professionals more effective, it will ultimately contribute to a more diverse legal profession.