Verna L. Williams

CEO

Equal Justice Works

Our nation is experiencing an access to justice crisis. According to the Legal Service Corporation, 92% of low-income people’s civil legal needs went unmet in 2022, leaving a massive gap in our justice system. What’s more, the number of lawyers focusing on underserved populations is very small. According to the American Bar Association, fewer than one percent of lawyers are paid legal aid attorneys. As law schools plan for the coming academic year, I urge them to consider how to address this untenable gap in our legal system.

Put simply, creating lasting change for communities and in our justice system requires more graduates to choose public interest law. The fact that so few law graduates pursue this route is not only problematic, but also puzzling. As a law school dean, I saw first-hand that many aspiring attorneys chose legal education because they wanted to serve the public. In my new position as CEO of Equal Justice Works, a nonprofit that connects law students, law school professionals, lawyers, and advocates with fellowships at legal services organizations and other opportunities in public interest law, we are tackling this problem head on.

Consider student loan debt. AccessLex reports that, on average, law students borrowed $157,300 last year. Students of color graduate with an average educational debt twice the amount of their white classmates. With entry-level public interest attorneys earning a median $63,200, compared to $200,000 for law firm associates, it’s hardly surprising that so many graduates would choose private practice.

What else explains the dearth of public interest attorneys? To answer that question, Equal Justice Works partnered with the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), an invaluable resource, to identify blind spots in supporting future public interest lawyers. Working with LSSSE, we crafted questions for the 2023 LSSSE Survey to help quantify just how accessible information about pursuing public interest law is for law students across surveyed law schools.

The results illustrate that many opportunities exist for legal education to build or strengthen support for new public interest lawyers. Among the findings:

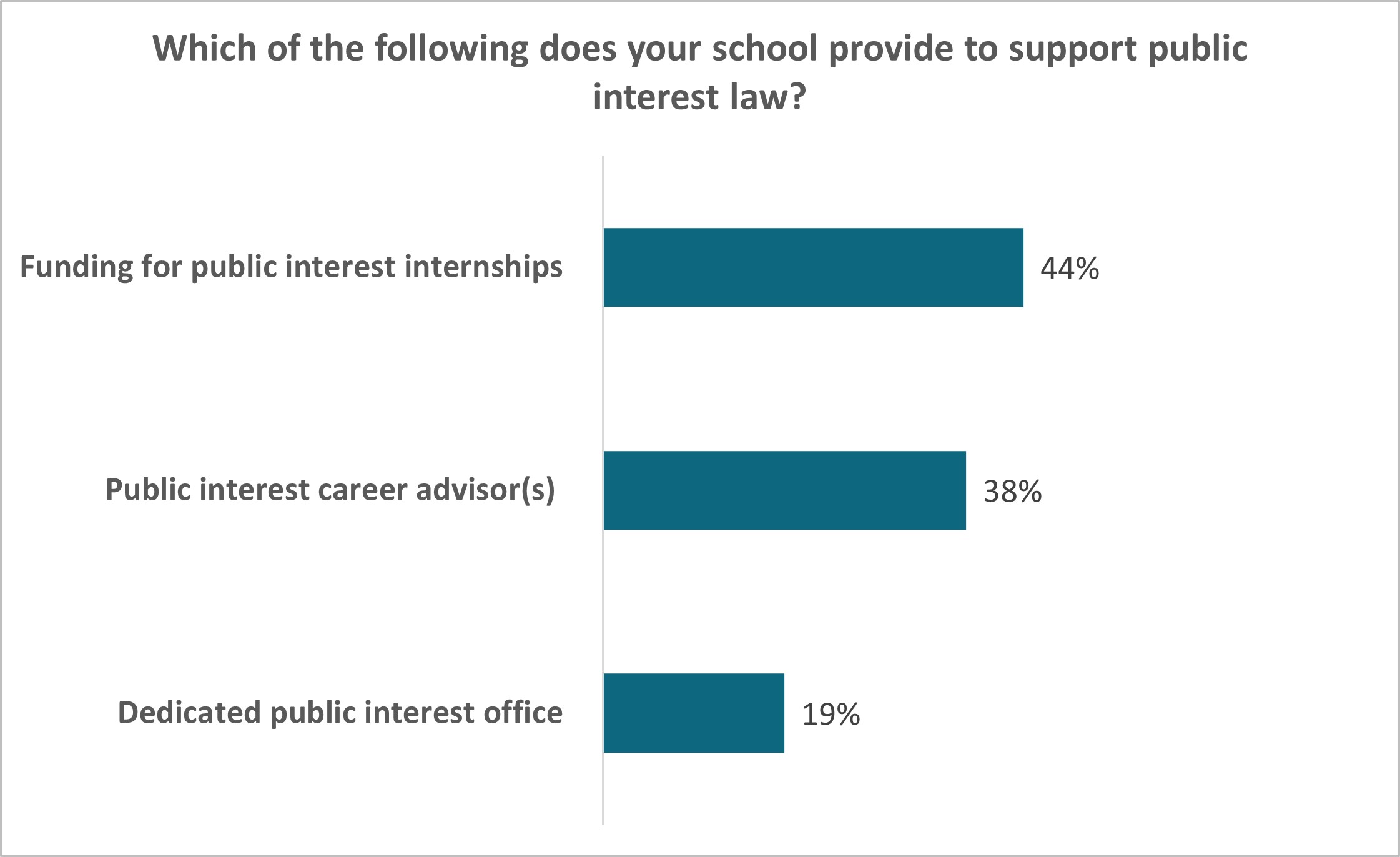

- Only 44% of participating schools provide funding for public interest internships.

- An even smaller percentage of schools, 38%, employ public interest career advisors.

- Just 19% of law schools have a dedicated public interest office.

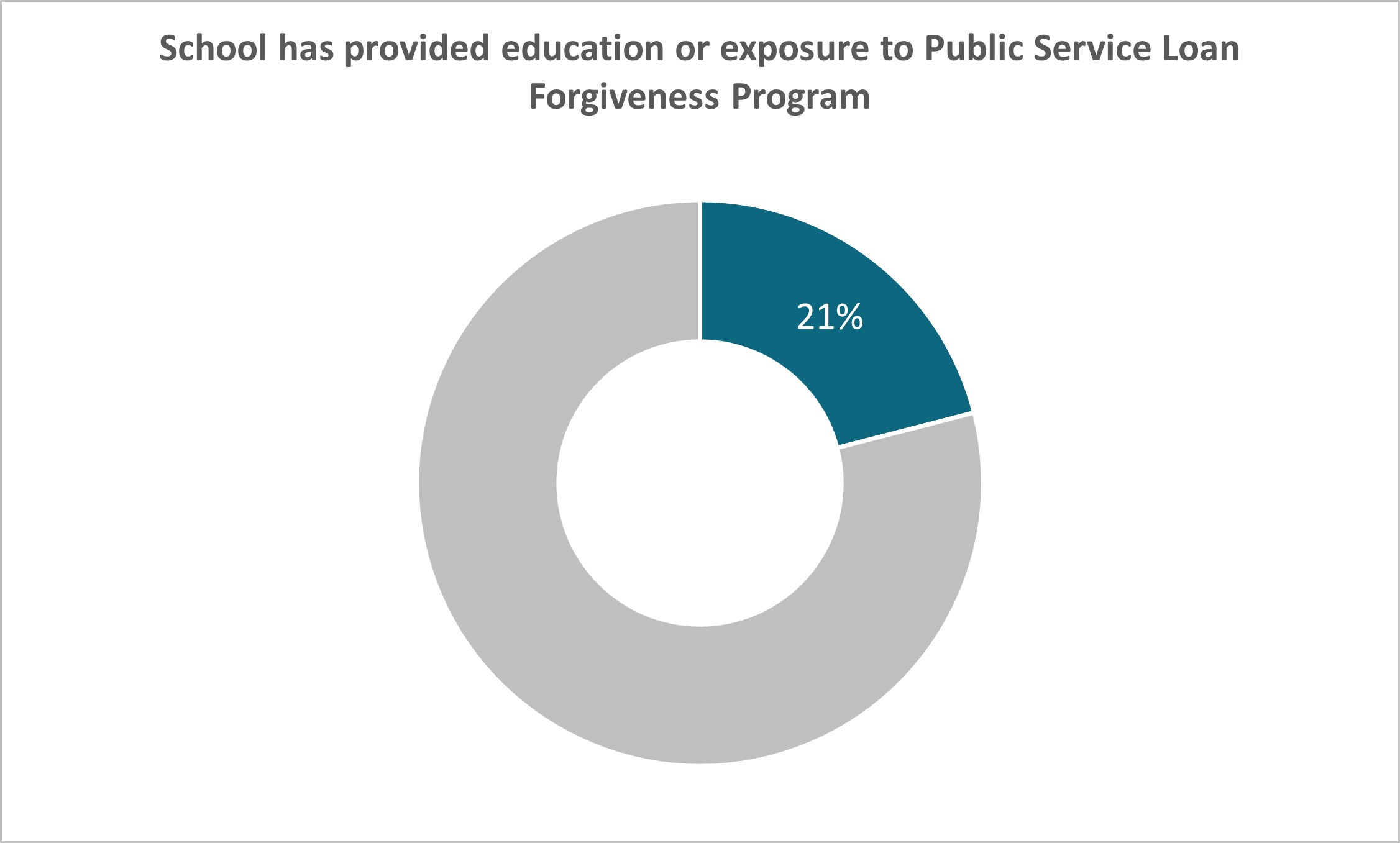

- When asked whether their school provided education and exposure to tools like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), the answer was a disheartening 21% responded in the affirmative.

The result is a knowledge gap about how to make the most of existing resources that can make pursuing public interest feel less like fantasy and more of a reality.

The LSSSE survey results strike a chord in me. Like today’s students, I chose law school because I wanted to make a difference. But before I began my public interest journey, I practiced in BigLaw to get my financial house in order—when I graduated, loan repayment assistance plans were brand new. I was able to get settled with my associate’s salary, paid off some debt, and never looked back.

My debt was considerably less than that of today’s student – but no less frightening. I wouldn’t trade my trajectory for anything, having had the privilege of practicing at the Department of Justice and the National Women’s Law Center. I built on those experiences as a faculty member at the University of Cincinnati College of Law (UC), in part, to create and support the next generation of feminist legal advocates. As a faculty member, I co-founded and co-directed the Nathaniel Jones Center for Race, Gender, and Social Justice, through which we created a clinic, advised students seeking public interest fellowships, and put on programs about how to “make a difference while making a buck.” Serving as dean of the law school allowed me to facilitate other efforts to make public interest opportunities available to students. I’m especially proud of the partnership we engaged in with Hamilton County Municipal Court to create the Help Center, which provided assistance to unrepresented litigants. Staffed by a UC attorney, the Help Center engaged students and volunteer lawyers who together have served tens of thousands of people.

Now, at the helm of Equal Justice Works, my colleagues and I continue the longstanding work of building a movement of public interest leaders who are transforming the communities we live in, come from, and partner with. But we can’t do it alone.

These survey results remind us we have a long way to go. But we are in this for the long haul. Partnerships with law schools are a key part of our strategy. We support member law schools, the majority of accredited institutions in the nation, in myriad ways —from educating law school professionals through webinars and other informational resources or introducing thousands of students to the field in the nation’s largest public interest career fair, to preparing them for such careers through summer fellowships and our Public Interest Primer. In addition to those resources, our law school engagement and advocacy team travels the country, visiting member schools to meet with students and share information about our programs and opportunities. Through these efforts and more, Equal Justice Works seeks to fill in the gaps about public interest law for students. Thanks to the LSSSE survey, we have important information to help amplify our efforts.

When millions of people in the United States cannot access legal assistance to avoid eviction, maintain custody of their children, or escape an abusive partner, we need an all-hands-on deck solution. Every part of the legal profession must focus on this crisis. Law schools must continue to institutionalize their commitment to pro bono work and public service. By continuing to work together, we can empower this next generation of advocates to be ready to direct their passion for impact where it’s most necessary.