Gregory S. Parks

Professor of Law

Wake Forest University School of Law

Etienne C. Toussaint

Associate Professor of Law

University of South Carolina Joseph F. Rice School of Law

In the first seventy-three years of the Virginia Law Review’s existence, there were no Black members. In 1987, three Black students were welcomed as members of the Virginia Law Review, two of whom were invited because of a newly implemented affirmative action plan. Yet, it would take until 2021—approximately 108 years after the law journal’s establishment—for the Virginia Law Review to elect its first Black Editor-in-Chief (“EIC”), Tiffany Mickel. Some might argue that this narrative merely reflects the difficulty of joining, much less leading, one of the nation’s most prestigious law journals at one of its top-ranked law schools where the enrollment of Black students is routinely low. After all, Mickel is exceptional among Black law students nationwide as one of only a few Black women in the United States with a materials science and engineering degree from MIT. Yet, the Virginia Law Review’s story appears to be more of an illuminating trend concerning law review’s diversity problem than a heroic triumph for Black law students.

For example, in January 2022, Texas Law Review elected Jason Onyediri as its first Black EIC, after nearly 100 years of the journal’s existence, and Bradford McGann became Northwestern Law Review’s first Black EIC. More recently, in 2024, the Harvard Law Review elected law student Sophia Hunt as only its second Black woman president in 137 years. In fact, of the less than seventy Black EICs from the top 100 law schools across U.S. history, more than half were elected in the past ten years. What inspired the dramatic increase in the diversity of law review leadership in recent history, and why has it taken so long?

This question—what we call law review’s “diversity problem”—does not have an easy answer. While legal scholars have been talking about diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”) on law review boards for far longer than the past decade, no American law school has yet to solve it. Since at least the 1980s, scholars have studied the impact of affirmative action policies on the diversity of law review boards. Early studies revealed that law reviews that did not have an affirmative action program often had no non-White members at all, much less in positions of leadership on the editorial board. Further, these studies showed that law reviews that implemented a mixed-method editor selection process (e.g., assessing first-year grades alongside performance on a writing competition) only fared slightly better.

Few law reviews have implemented structural changes to both the editor selection and scholarship publication process. As a result, DEI on law reviews remains low. Further, even as law schools push for greater DEI in the classroom, few law schools seem to be concerned with the diversity of their law review boards.

Critics of affirmative action and progressive DEI efforts argue that law school’s so-called diversity problem does not imply that law schools are failing their law students or their local communities. Rather, they argue, too few qualified racially and ethnically minoritized students are applying to and enrolling in law school. Perhaps law review’s diversity problem is a symptom of law schools’ failure to admit more underrepresented students? Or, perhaps there is a lack of interest among Black students to join the law review and rise to leadership? We disagree. And the data support us.

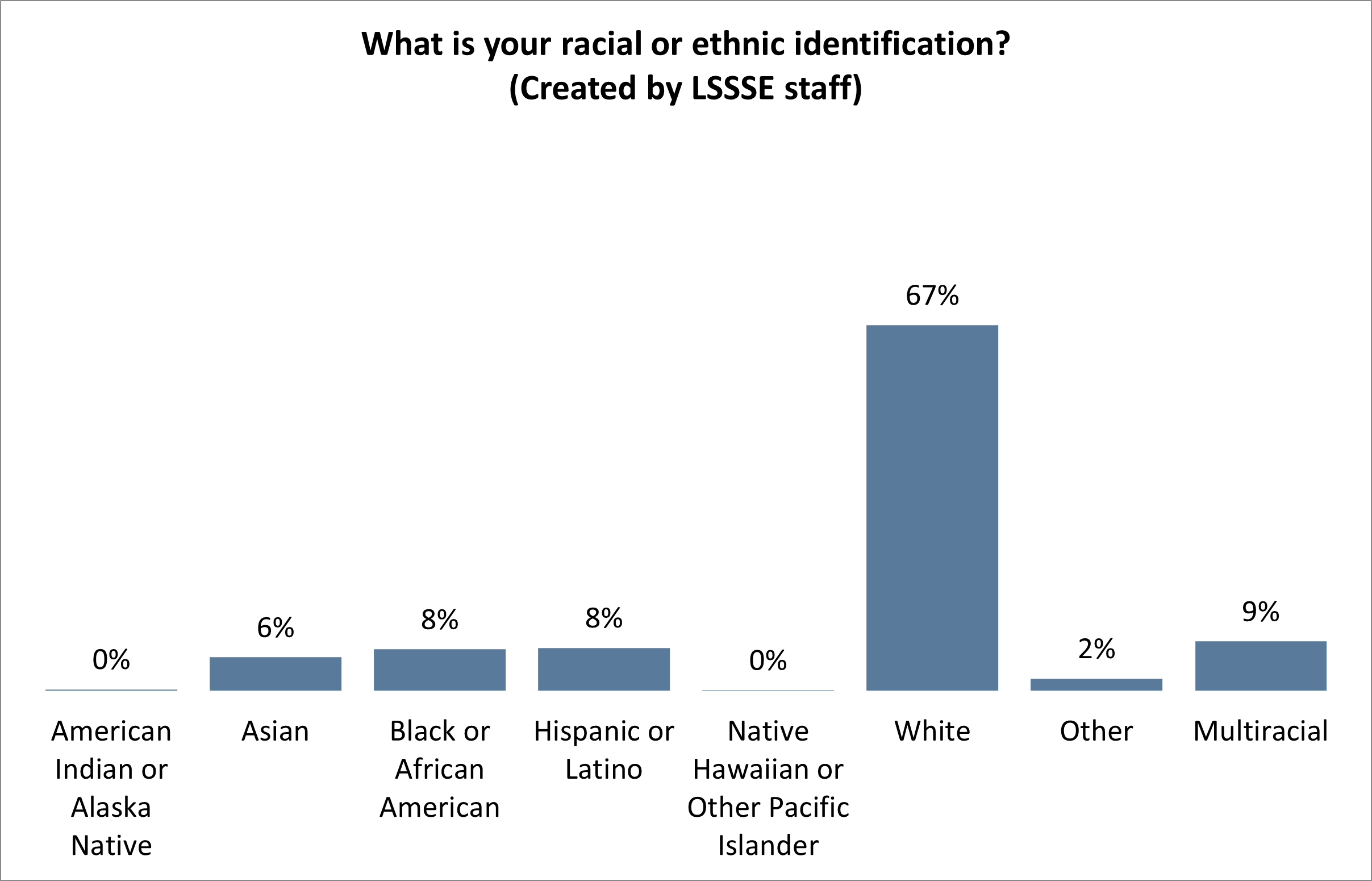

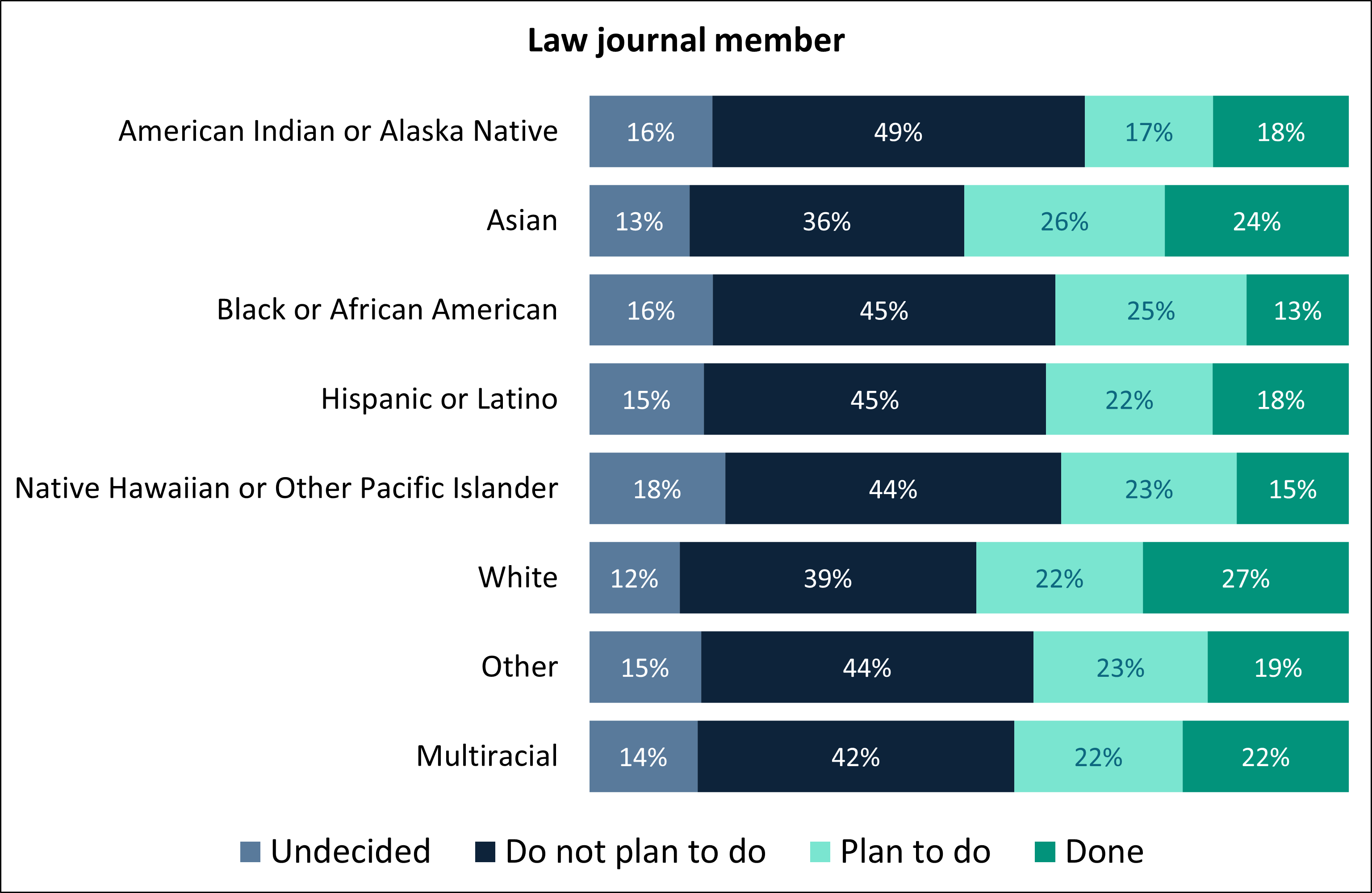

LSSSE data reveal that roughly 8% of current law students are Black. Still, while White students remain the majority (67%), many Black students continue to pursue opportunities to join and lead the law review. Furthermore, there is significant interest among Black students in joining other law journals. Approximately 13% of Black LSSSE respondents note that they have already joined a law journal and an additional 25% note that they plan to do so in the future. Accordingly, the (lack of) participation and leadership of Black law students on law reviews does not reflect apathy.

We believe that law review’s diversity problem must be engaged in the broader context of two complementary lenses: (1) sociopolitical efforts to eradicate racial injustice; and (2) institutional efforts to reform legal education.

On the one hand, the lens of socio-politics suggests that DEI efforts in law reviews experience the push and pull of racial attitudes and perceptions across the nation. For example, researchers have shown that although the election of President Barack Obama in 2008 improved the public’s perception of Black people’s work ethic and intelligence, racial attitudes became more polarized between 2009 and 2013, coinciding with an increased number of racially motivated killings of Black people nationwide. Nationwide calls for racial reckoning in the summer of 2020 after the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, among others, coincided with a dramatic uptick in Black EICs in 2021 and 2022. Accordingly, at least one driver of the increased attention to DEI issues in law reviews during the past ten years may be attributed to the increased attention nationwide to racial justice issues since President Obama’s election.

On the other hand, DEI efforts in law reviews also experience the push and pull of racial attitudes and perceptions across their law school community, including the views and attitudes of their faculty. Consider the current project of “building an Antiracist law school,” as Dean Danielle M. Conway of Penn State Dickinson Law puts it, that has been decades in the making. That effort has only been amplified in recent years, with law faculty increasingly prioritizing racial justice in their teaching and scholarship. Therefore, another driver of the increased attention to DEI issues in law reviews during the past ten years could be law professors’ increased attention to modern social movements, such as the Movement for Black Lives.

We argue that there are three fundamental drivers of law review’s diversity problem, with implications not just for law reviews, but for legal education writ large. First, there is confusion on the purpose of DEI. The purpose of DEI for law reviews is not solely to increase diversity on the law review roster to enhance the learning experience of students on the journal. A deeper purpose of DEI, we argue, is to realign the distorted function of the law review with its ideal purpose. While one of law review’s fundamental purposes is to promote scholarly discourse on law and law reform to promote the public’s interest, in practice, many law reviews serve merely as a gatekeeper for elite law practice and prestigious clerkships.

Second, there is confusion on the role that DEI plays in the legal education experience. The role of DEI for law reviews is not merely to increase the equality of opportunities for underrepresented students, nor simply to increase the discussion of marginalized experiences and diverse perspectives of law in public forums. We argue that the role of DEI is to articulate a more ambitious conception of “equity” in law, political economy, and legal education. As Lani Guinier argued, the very concept of meritocracy that governs how racially and ethnically minoritized students pursue equitable outcomes on the pathway toward legal practice must be challenged as an historically limited vision of legal education.

Finally, the value of DEI for law reviews has been distorted. The value of DEI is not simply its ability to increase the number of marginalized voices in mainstream legal discourse. DEI efforts must also challenge the culture of mainstream legal discourse altogether. Challenging elitism in the legal profession, we argue, requires a bold critique of the toxic ideologies that color societal views on meritocracy and leadership, which can influence the very color of law review itself.

To be sure, the recent wave of Black law review EICs is a bold step in the right direction. However, more work remains to dismantle the gatekeeping function of law reviews and transform it into an educational space open to all law students and all members of the broader community.