Cyra Akila Choudhury

Professor of Law

FIU College of Law

Center for Law and Digital Technologies, Leiden University

Asian Americans have been in the news a great deal in the last several years. This year has been the year for Asians in the movies. Over the pandemic years, Asians and Asian Americans were in the news regularly for being victims of racial harassment and violence. That violence reached its extreme in the Atlanta massacre of six Korean American women working at a spa. The brief outpouring of support and solidarity after the shootings were welcome but not sustained. Within months, Asians went back to being a marginal minority group.

Even though we are the fastest growing minority, too often, we are only given attention in extraordinary moments: when we are the agents (Oscar winners, school shooters) or objects (victims of violence) of spectacular events. The most recent sustained attention given to Asian Americans has been in the context of the legal attacks on affirmative action.[1]

As Asians, we occupy the spotlight but not the sunlight, solidarity ebbs and flows, and our excellence is a double-edged sword. In this blog post, I reflect on the ways in which we have become agents for change in ways that overcome the binary glare of the spotlight or dark of its shadow. Asians have practiced and should continue to commit to radical solidarity both among ourselves and with other groups even as we unapologetically embrace our excellence. I offer these reflections as part of an ongoing conversation about what it means to be Asian American—an umbrella that includes a diverse group of people—in this moment.

- Seeking the sunlight not the spotlight

We are used to not being seen and not attracting attention to ourselves. Psychologist Jenny T. Wang writes in Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans,[2] that safety was one of the primary needs of her immigrant family. Safety meant following the plan of achieving stability and success without fuss. Often this means that we keep our heads down and get the job done, sacrificing what we truly love for the sake of duty. The light is shone on us by others when they perceive something worthy of notice.

In short, unless we are winning Oscars, running Google, or being massacred, people really don’t notice Asians. This is the spotlight effect. An external gaze that lights us up temporarily. As law students and lawyers, this might happen when we win an award or a big case. But what about when we’re not winning something? Asians deserve the sunlight and not the spotlight. That is to say, rather than being content with attention primarily when we achieve excellence, we deserve to be visible and present just as we are. Living in the sunlight also means being willing to be seen in our various workplaces and in society. Raising our hand in class, speaking in our own voice, running for public office, applying for promotion, and owning our histories and accomplishments.

- Practicing radical solidarity

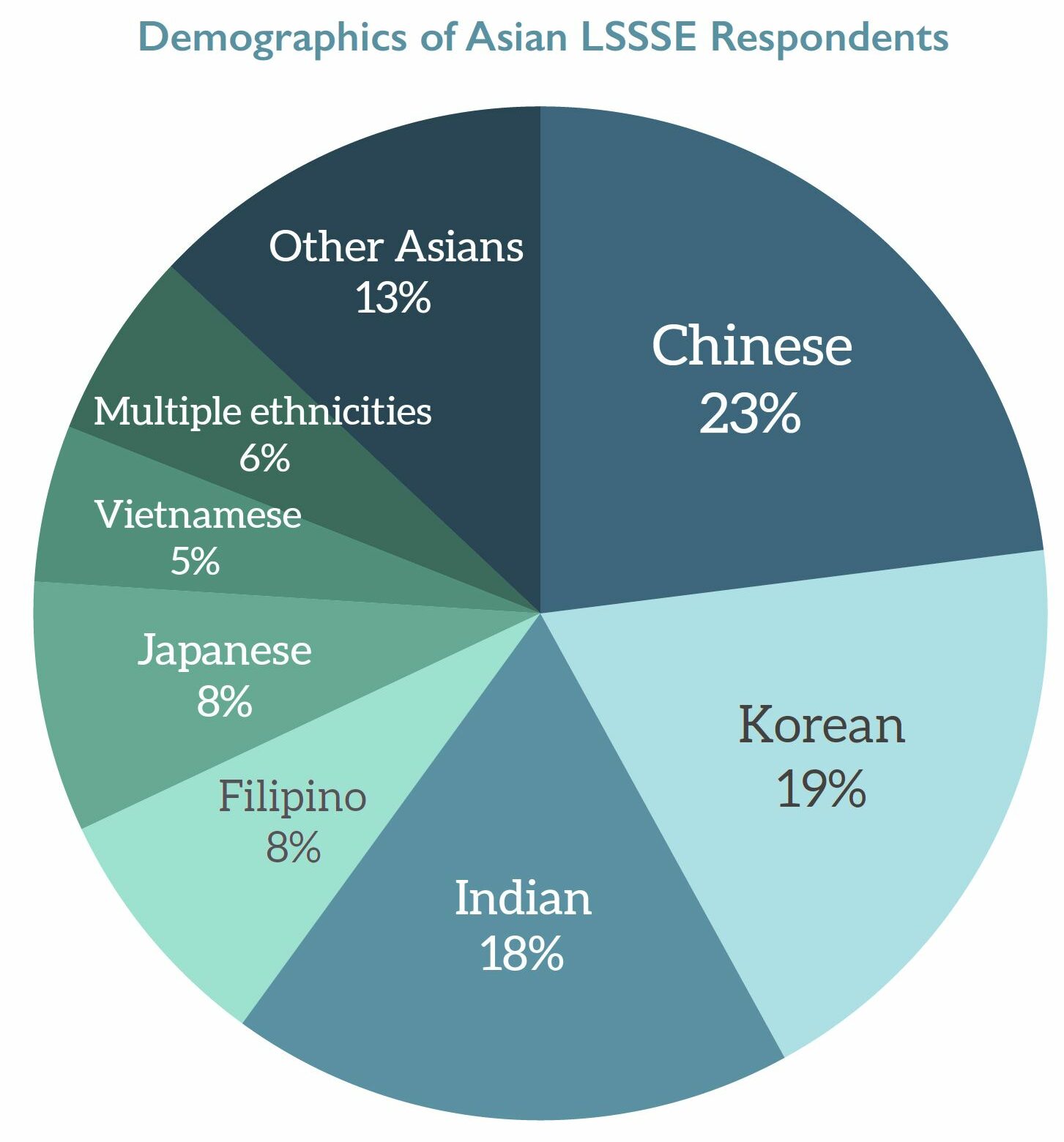

Asia is a vast geography with ancient civilizations. “Asian” is not a race, a cultural group, nor a linguistic group. Asian Americans hailing from different parts of Asia are a diverse group with many sub-diasporas. In legal education, for instance, Asian Americans include those with ancestors from China, Korea, India, the Philippines, Japan, and Vietnam. Increasingly, the shared experiences of these communities in the U.S. based on political marginalization, racism, immigration, and some cultural values have led to a growing sense of shared identity as well.

Yet, much more work needs to do be done to forge these nascent bonds. After the Atlanta massacre and the pandemic related violence against East Asian communities, there was a surge of broader recognition that Asian Americans were subjects of racism. This massacre was preceded by the massacre of six Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012. This too was an Asian massacre and yet, we rarely connect the two as anti-Asian racism. Solidarity among Asians in an increasingly polarized political society has become very important if we want to shape and direct change.

Yet, much more work needs to do be done to forge these nascent bonds. After the Atlanta massacre and the pandemic related violence against East Asian communities, there was a surge of broader recognition that Asian Americans were subjects of racism. This massacre was preceded by the massacre of six Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012. This too was an Asian massacre and yet, we rarely connect the two as anti-Asian racism. Solidarity among Asians in an increasingly polarized political society has become very important if we want to shape and direct change.

Asians have been partners in all of America’s struggles: the civil rights movement, labor rights, anti-war protests, and resistance to the War on Terror. We have demonstrated our solidarity with other groups, and we must do the same within our Asian communities as well. Radical solidarity, as I define it, means showing up for the struggle when called. When Black communities call for resistance, we show up. When Latinx communities ask for solidarity, we show up. Same for feminists and LGBTQ communities. We cannot succeed meaningfully in isolation. These struggles overlap within our communities. Moreover, radical solidarity is something we do without taking stock. I recall an acquaintance remarking in response to the Atlanta massacre, “I’d like to support Asians Americans, but they call the cops,” This is the opposite of radical solidarity. It is contingent solidarity and as we all know, fair-weather friends are of limited value. No single group has succeeded without radical solidarity from other groups. Without the civil rights movement, many of us would not even be Americans.

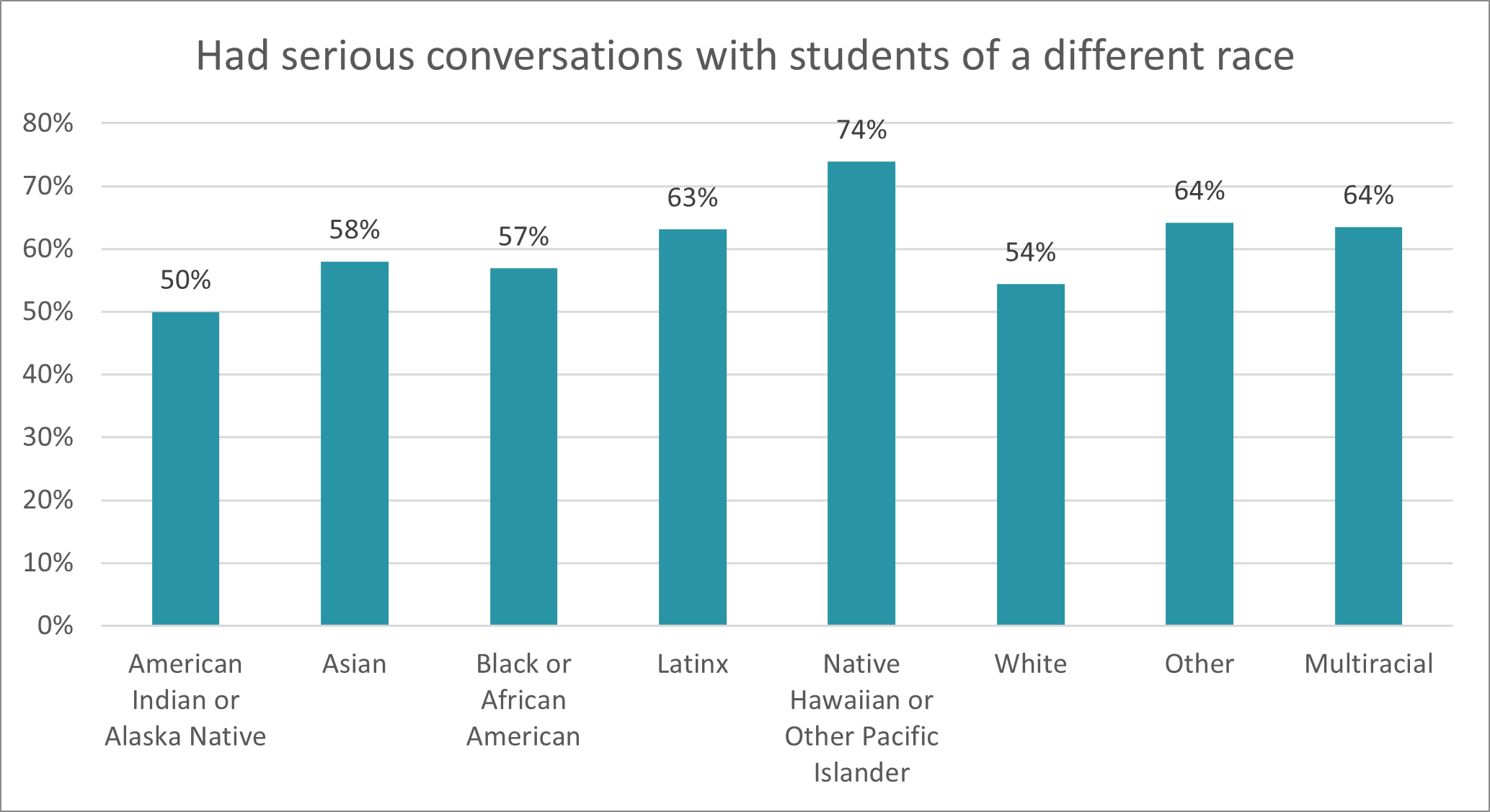

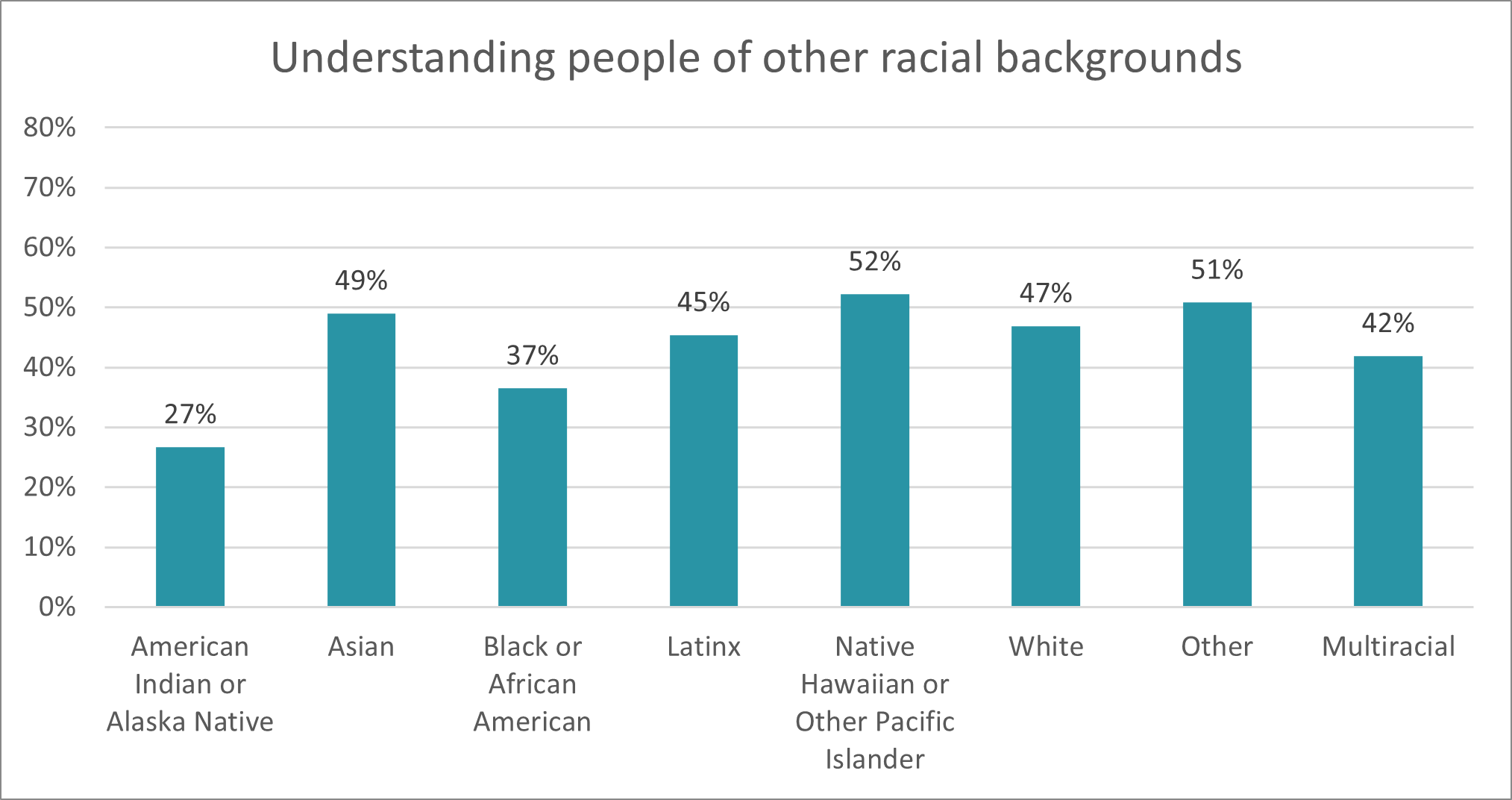

For law students, radical solidarity means working with other groups, showing up for their events, collaborating with others. LSSSE data make clear that law students excel at this already, both having serious conversations with students of a different race and working to understand students from different racial backgrounds.

For law professors, it means mentoring across various communities, perhaps reading across histories and cultures, and comparative research. For lawyers, it means building professional bridges and perhaps doing pro bono work for the communities that need it. Radical solidarity might require humility but not apology. I’m sure that there are many in our communities with very different ideas and politics but I speak here to the majority of us who believe in social equality.

- Embracing excellence and failure

Asians Americans are known as the “model minority.” It’s a pernicious myth about exceptionalism that is used to chastise other minority groups. In the last few years, weaponizing Asian excellence to harm other minority groups has been difficult for most Asians because we support affirmative action. How do we celebrate the very excellence that has been used to falsely exceptionalize us? Others have written extensively about the harms of this myth not only to others but to Asians themselves. Here I want to reflect on another consequence: a reluctance to embrace our successes and excellence as a community because it reinforces the myth.

The model minority myth has led to an ambivalence in celebrating our communities’ successes—an obstacle that few other groups have had to overcome. Achieving success because of hard work should be celebrated for itself while understanding that it says nothing about the value and success of any other group. Our radical solidarity with marginalized groups prevents us from claiming any exceptionalism for ourselves. And celebrating Asian Americans who succeed should not be mistaken for it. Nor should it be denigrated as mere borrowing, assimilationism, or white adjacency which is another kind of negative exceptionalism. Other groups’ similar successes are rarely spoken of in these denigrating ways.

So, celebrate the Indian kids who win spelling bees, the Chinese kid who wins the math competition while rejecting that Asians are somehow exceptional at spelling or math! Our stars are just that: stars. We have exceptional talents who deserve to be celebrated.

I want to end on a positive note on what is commonly thought to be a negative experience: failure. One stereotype about Asians is that, in our families and communities, failure is not an option. However, we should embrace failure as part of success rather than as a shameful shortcoming. As a law professor, I tell my students that they should learn from their failures, admit to them, overcome them, and move forward. Failures are inevitable and learning to cope with them without shame is important to the mental health of the community.[3] Asians fail as much as any other group and to deny this is to enforce an unacceptably high standard. To fully lay the model minority myth at rest, we must accept both our success and our failure. Asian belonging is not contingent on group accomplishment or excellence. We deserve the sunlight, to be visible, and fully accepted as Americans when we’re winning as well as when we’re not.

____

[1] Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard; Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina

[2] Jenny T. Wang, Ph.D., Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans (2023).

[3] See id.