Guest Post

Marsha Griggs

Associate Professor of Law

Saint Louis University School of Law

The BlueBook® is in its twenty-first edition and for the last fifteen years has been available online as well as in its original spiral-bound print version.[1] I could not imagine publishing a Law Review article, submitting a court brief, or teaching a Legal Writing course without consulting the most current edition of the BlueBook. Although I don’t care about uniform citation guides for my day-to-day writing tasks, I understand the expectation of proper citation for formal writing projects.

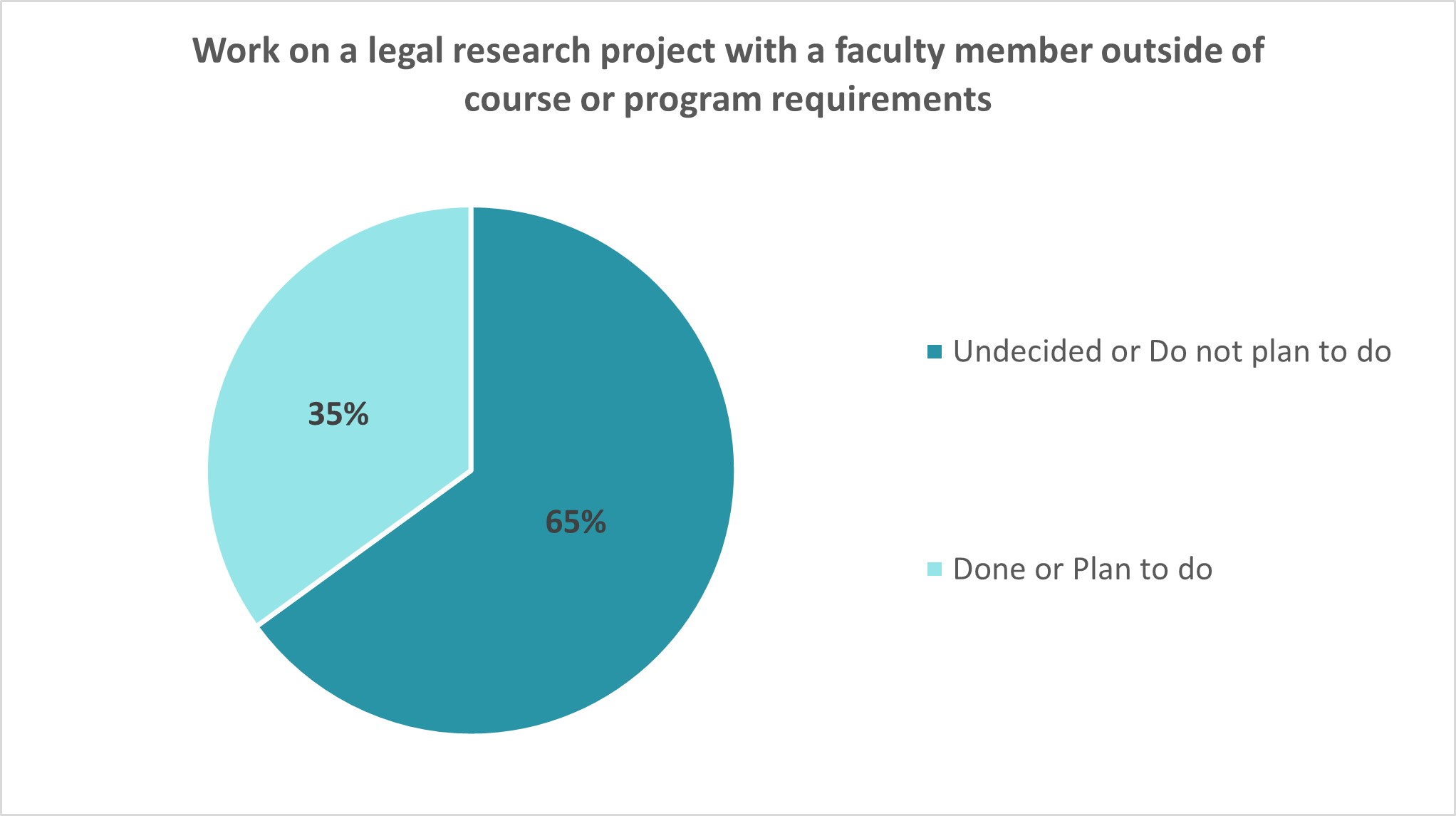

To meet that expectation, I gratefully rely upon my research assistants and the meticulous eye of journal editors. I am out of practice with my “blue booking” skills, because I consistently hire someone else to do it for me. I know that many other mid-career faculty and law practitioners can relate. Thankfully, LSSSE Survey data show that law students benefit from working on legal research tasks with faculty outside of class assignments. Although student research responsibilities for faculty and journals often fall outside the experiential education radar, these tasks are important to practice readiness.

While it is perfectly fine for me to outsource necessary cite checking to a student or even to an A.I. tool like ChatGPT, I am still ultimately responsible for my written product. The same is true about our professional responsibilities as lawyers. We can and should rely on available technology and skilled providers who can aid us in delivering legal services and establishing and enforcing laws and policies. But we must do so with a conscious awareness that tools, practices, policies, and laws are constantly subject to change.

Lawyers and legal educators have an ethical obligation to engage in continuing study and education to keep abreast of changes in law practice and legal rules, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.[2] That obligation includes keeping up with changing rules for attorney licensure. Yet very few law professors and even fewer attorneys in practice understand the previous and proposed sweeping changes in attorney admission, including who creates and controls the bar exam.

Outsourcing a specific legal task—like research or cite checking, is not the same thing as outsourcing a regulatory function—like licensing attorneys. In a forthcoming article, Outsourcing Self-Regulation, I address how states have contracted with outside providers to produce bar exam questions and to score the exams. Like my outsourced blue booking, it saves time and results in a higher quality product. But when the outsourcing of a responsibility is combined with inattention or lack of supervisory accountability, it becomes delegation of a regulatory power or duty. Such a shifting of regulatory authority threatens the autonomy of the legal profession.

Today, bar exam questions are almost uniformly written and selected by the NCBE. [3] The NCBE has successfully lobbied for a single unform exam to replace the varied individual state law exams. The widespread adoption of a Uniform Bar Exam has privatized bar admission to the point that states no longer have control (or even input) into the content, scope, or timing of their licensing exam. The privatization of the bar exam is at odds with the cornerstone principle of resolute self-regulation and freedom from external influence.

The planned debut of the NextGen bar exam in 2026 threatens to further weaken the judicial autonomy in attorney admission.[4] Dangerously little is known about this new exam and law schools too are fully at the mercy of NCBE for crumbs of information about the next exam. We cannot effectively help our students to prepare for licensure if we ourselves are unfamiliar with the licensure exam and its format and cannot verify its validity.

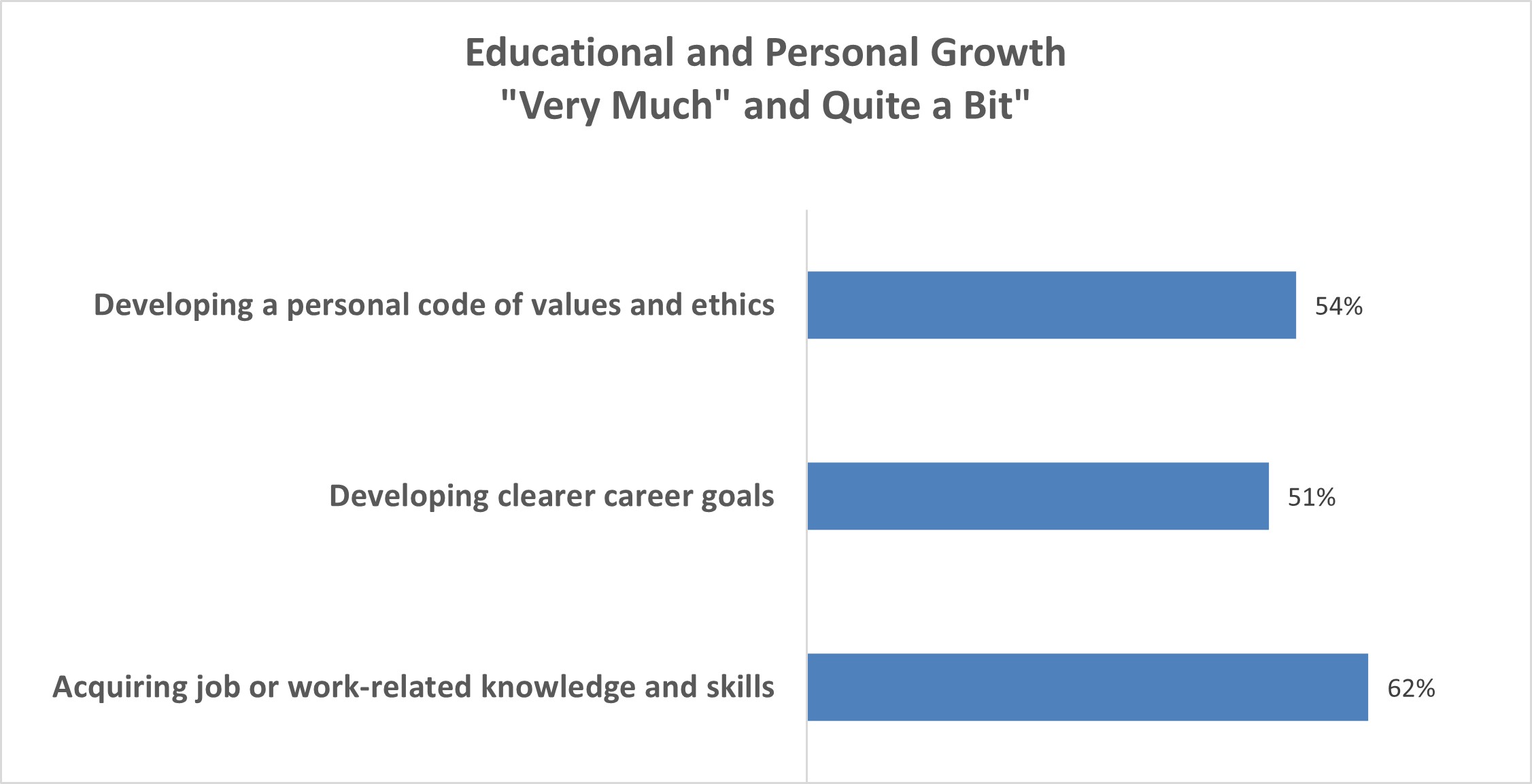

The LSSSE Survey data show that law students feel that law schools have generally prepared them for work-related tasks and supported them in developing career goals and personal ethics.

A quantifiable component of preparing law students for the practice of law is preparing them for the bar exam that allows them entry into law practice.

The pathway to becoming an attorney in the United States typically involves attending and graduating from law school, and successful completion of some competency assessment. All but a few U.S. jurisdictions use performance on a bar examination as a proxy for minimum competence to practice law. Since the genesis of licensure by examination, the format, content, scoring, and source of bar exams have been contentious issues in the legal profession.[5] The arguments for and against the use of bar exams are too great to list or summarize here, but—however it is measured—law schools are responsible for ensuring that their graduates are minimally competent to deliver legal services directly to clients upon completion of the program of legal education.

As members of a self-regulated profession, we have a responsibility not only to know about the scope of the regulatory exam, but also to set the standards for what the regulatory exam should measure and how it should do so. We must pay attention to developments in attorney licensing if we aim to continue to meet the needs of our students who will pursue licensure.

___

[1] The BlueBook: A Uniform System of Citation R.15.8(c)(v), at 154 (Columbia L. Rev. Ass’n et al. eds., 21st ed. 2020).

[2] American Bar Assoc’n Model Rule of Professional Conduct 1.1 Comment 8.

[3] The National Conference of Bar Examiners is a not-for-profit corporation with its principal office in Wisconsin. https://www.ncbex.org/about/media-kit/

[4] https://nextgenbarexam.ncbex.org/

[5] See e.g. Joan W. Howarth, Shaping the Bar: The Future of Attorney Licensing (2023), and Marsha Griggs, Building a Better Bar Exam, 7 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 1 (2019).