Improve the Diversity of the Profession By Addressing the Costs of Becoming a Lawyer

Joan Howarth

Professor Emerita, Boyd School of Law, UNLV

Dean Emerita, Michigan State University College of Law

One of the themes of my book, Shaping the Bar: The Future of Attorney Licensing (Stanford University Press 2023), is that becoming a lawyer in the United States is too expensive. Unlike in many other countries, the U.S. law degree typically requires three or four years of expensive postgraduate study, which should be enough time to produce and assess minimum competence to practice law. But after graduating from law school bar candidates typically spend two more months and thousands of dollars immersed in bar prep with a commercial company. The billion-dollar bar prep industry covers the gap between what was learned in law school and what is required to pass a bar exam. Student loans do not cover the cost of those bar prep courses or the living expenses while preparing for the exam. Law graduates without financial resources face financial emergencies – or time-consuming jobs for paychecks — when they are supposed to be using all their time preparing for the bar exam.

Not surprisingly, then, research shows that economic assets are a significant factor in bar passage. And LSSSE research shows us the connections between the excessive expense of becoming a lawyer and the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in bar passage rate.

The racial and ethnic bar passage disparities are extreme. For example, the national ABA statistics for first time passers in 2023-24 show White candidates passing at 83%, compared to Black candidates (57%) with Asians and Hispanics in the middle (75% and 69%, respectively).

These disturbing figures are very related to the expense of becoming a lawyer.

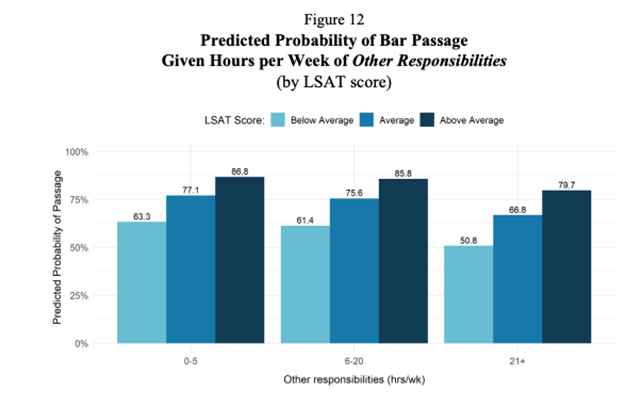

The 2021 National Report of Findings for the AccessLex/LSSSE Bar Exam Success Initiative showed that law grads who take care of children or work in non-law jobs have a harder time passing bar exams.

These problems were confirmed in a large 2021 study of New York bar takers. Even after controlling for LSAT and other academic factors, law grads who had greater financial resources were significantly more likely to pass but grads who worked for pay were significantly less likely to pass.

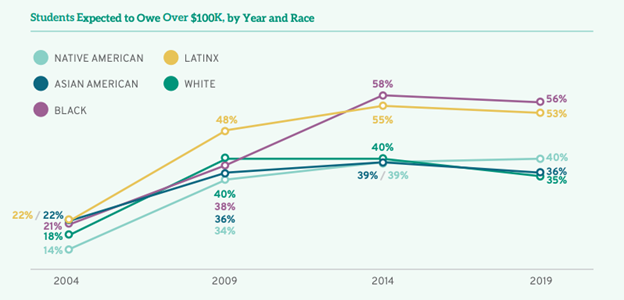

Who are the law grads with fewer financial resources? LSSSE research shows us that Black and Latinx students are carrying more law school debt than White students.

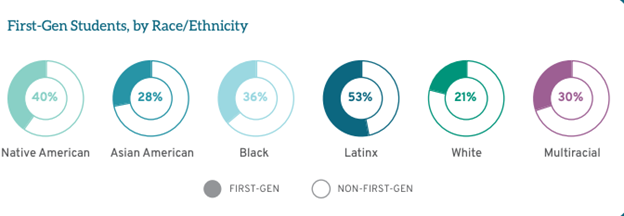

LSSSE’s 2023 Annual Report focused on first-gen law students shows that law students who are the first in their families to graduate from college are more likely to be from underrepresented communities.

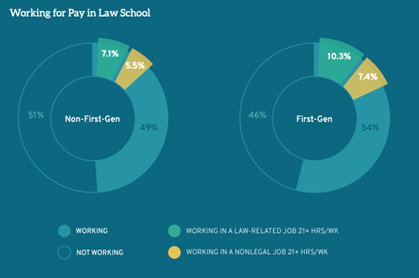

First-gen students are also more likely to work for money and work in non-law related jobs in law school.

LSSSE data from that report show that first-gen law students are also more likely to care for dependents.

In other words, law graduates who could be great lawyers—too many of whom are people of color, first-generation law students, and parents—are failing bar exams because they cannot drop everything else for two months to devote themselves to memorizing thousands of rules, most of which they would not use in practicing law, and most of which they will forget quickly after walking out of the exam.

Finally, though, after decades of stability — or stagnation — in attorney licensing, change is here. And some of the changes, such as the new pathway to licensure in Oregon based on supervised practice instead of a traditional bar exam, or the Nevada Plan in which most of the requirements can be satisfied during law school, should significantly decrease the costs of licensure and add flexibility for candidates with responsibilities beyond studying for a bar exam. These reforms are long overdue.