Guest Post: Rising With the Tide: Using National and Off-Cycle LSSSE Data to Improve Practice and Scholarship

Rising With the Tide: Using National and Off-Cycle LSSSE Data to Improve Practice and Scholarship

Rising With the Tide: Using National and Off-Cycle LSSSE Data to Improve Practice and Scholarship

Trent Kennedy, MA, JD

National LSSSE data are a valuable and oft-overlooked resource to improve scholarship and data-informed practice. Their free online Public Reporting Tool gives everyone access to aggregated data from the last eight years of LSSSE administrations, allowing for quick checks and relatively detailed dives. Researchers and administrators who are interested in testing assumptions, building theories across data sources, and leveraging national norms should keep it in mind as their projects take shape.

The demographics of LSSSE participants reflect those of US law students overall (at least as of 2017). A total of 181 US law schools have participated in LSSSE since 2004, and each year’s cohort contains law schools from up and down the US News and World Report ratings (and one of my favorite data visualizations in legal education reminds us that it is a rating), capturing institutional diversity as well as student demographics.

Student Affairs professionals, faculty members, and administrators can use the Public Reporting Tool for a number of different useful functions, which are especially powerful when combined with school-specific data.

Testing Assumptions

National LSSSE data allow users to test myths, assumptions, and meso-ideas about law student characteristics and experiences. For example, after noting that 27.1-29.2% of LSSSE participants between 2014 and 2019 reported being first-generation college graduates, Georgetown Law began to investigate the experiences of our own first-generation students, law student affairs professionals from across the country engaged more deeply with the NASPA Center for First-Generation Student Success, and the AALS Section on Student Services is exploring a collaborative program about the needs of first-generation students writ large. As the old assumptions about our student populations become less and less useful, local and national data will help identify needs and marshal resources for the future of legal education.

National LSSSE data also show a consistent decline in overall satisfaction and preference for the same law school as JD students progress from 1L to 3L year. Students in their 3L year will certainly have more experience with and information about their law school, but local data are needed to know if they will really be the best boosters to alumni or prospective students.

Norming

The converse of assumption testing is establishing norms that can be leveraged to influence student behavior. Social norming is a common technique in public health communication, often used to combat perceived isolation as a barrier to healthier behavior. In 2017, my office was struck by the national data around the LSSSE core survey question 6c “In your experience at your law school, how satisfied are you with: Personal counseling?”. Of 20,574 students surveyed that year, 9,132 indicated that they had not used personal counseling while in law school. The actual satisfaction of the remaining 11,442 students ran the gamut, but careful observers will note that 55.6% of JD students participating in LSSSE indicated some uptake of personal counseling services (as distinguished from academic advising, career counseling, and financial aid advising). With so many of our students convinced that they are the only one struggling, seeing flyers around campus with a majority message to the contrary is a powerful sign that vulnerability and help-seeking are nothing to be ashamed of.

In the same vein, national LSSSE data on law student time use helped us build a norming campaign intended to reduce students’ overall stress and sense of time famine (the belief that you have too much to do and too little time to do it all). A quick run through the 2017 LSSSE data showed us that 1Ls spend an average of 31.93 hours per week reading and preparing for class. With 15 hours of weekly classroom instruction for Georgetown Law 1Ls at the time of the project and even factoring in a full night’s sleep each night, that leaves students with plenty of hours per week of waking time not spent in class or studying. That should be around 65 hours to enjoy their meals, visit the gym, talk with their families, or explore the community around them. From our conversations with students and other LSSSE data, we know they don't feel like they have that much time and spend their hours according to that feeling. We wanted to break them out of the cycle of stress and time famine. We presented the LSSSE data on time spent studying and the ensuing arithmetic on other available time during 1L Orientation in the hopes of relieving perceived time pressure, encouraging self-sustaining behavior, and restoring a sense of control to our 1Ls’ lives. A minority of the student feedback still showed the perennial hobgoblin of anxious peer comparison, but the response from the majority of students (and a few visiting alumni) was positive. They wanted the intended outcome and trusted a norm articulated with national data.

Scholarly Corroboration, Synthesis, and Theory-Building Across Data Sets

National LSSSE data can also be used to corroborate or support local data, allowing for the development of theories across multiple data sets. Law student stress has been a perennial topic of interest, rising in perceived importance as post-recession career pressure continues to haunt current students. Segerstrom’s idiosyncratic instrument revealed time pressure, difficulty of material, and lack of feedback to be chief concerns of law students in the late 1990s but “academic environment” was not. National 2015 LSSSE data from a special module on law student stress reported both the overall level of stress and the major sources of that stress, finding that academic performance and academic workload were the most common concerns while classroom environment/teaching methods was the least common. Flynn, Li, and Sánchez’s 2019 study of law student stress found that workload pressure was the strongest predictor of law student distress, but that course design and grading failed to show statistically significant relationships with the expected distress outcomes. Interested scholars might struggle to meaningfully synthesize Segerstrom and Flynn et al. without the intervening LSSSE data that facilitate a clearer focus on student perceptions rather than the institutional structures that produce them.

Even without timely local data, national and off-cycle LSSSE data enhance other avenues for scholarship and practice. By making the most of that data, legal educators can check their assumptions about student demographics and behavior, make new norms visible to change student attitudes, and connect other data sets into a more coherent (and actionable) landscape. Scholars and practitioners would do well to consider national LSSSE data when looking for insights on a proposal, program, or institutional problem.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 4)

The Troubling Secret to Success

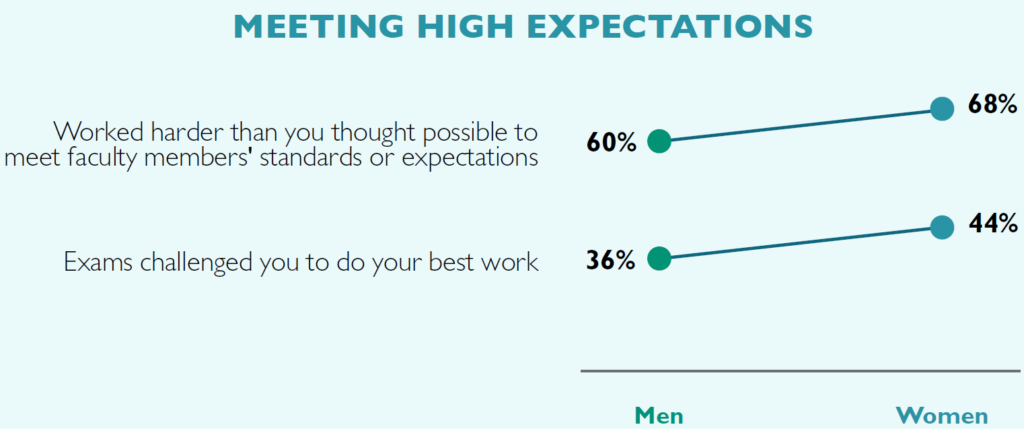

What is the secret to the success of female law students? They enter law school with fewer resources and amass significant burdens once enrolled, but perform at equal or higher levels than their male peers along many metrics. The data suggest one clear answer: women law students work extraordinarily hard, juggling their various personal and academic responsibilities at the expense of self-care. While most students work hard to meet the high expectations of their professors, women students report sustained effort at higher levels than their male peers. A full 68% of women note that they “Often” or “Very Often” worked harder than they thought they could to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations, compared to 60% of men. Similarly, higher percentages of female students than male rise to the challenge of submitting their best work on exams. LSSSE respondents were asked to report “the extent to which your examinations during the current school year have challenged you to do your best work” on a 7-point scale. Remarkably, 44% of women report the highest level of engagement (a 7 out of 7) as compared to 36% of men. Again, these findings of hardworking women are consistent across race/ethnicity.

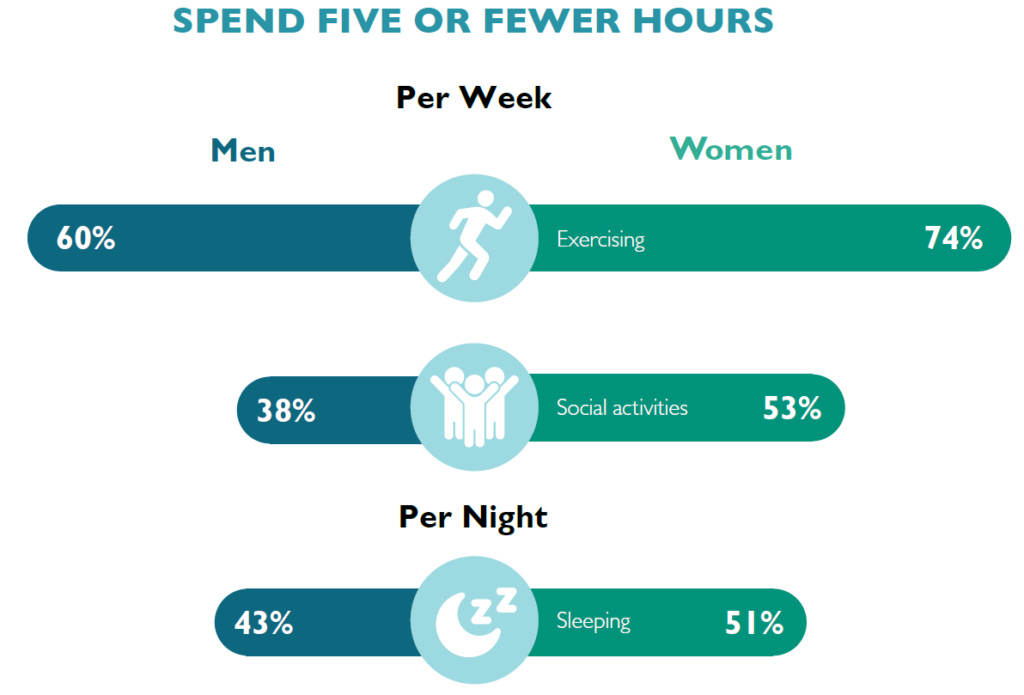

Tragically, the hard work that women dedicate to enabling their success comes at a significant cost. The tradeoff is that women are much less likely than men to engage in important social, leisure, and self-care activities. Each of these findings is consistent across racial/ethnic groups when comparing women with men. For instance, 41% of women spend zero hours per week reading for pleasure, compared to 25% of men. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of women law students find little time for physical fitness, with 74% reporting that they exercise no more than 5 hours a week (along with 60% of men). Expanding this concept to other leisure activities—including watching TV, relaxing, or even partying—does not improve this gender disparity. More than half (53%) of women law students spend five or fewer hours per week engaged in any of these social activities, compared to just over a third (38%) of men. Furthermore, half (51%) of women report sleeping five or fewer hours per night in an average week, along with 43% of men. In the scramble to get ahead academically, women are overlooking downtime; they are prioritizing their academic success at the expense of their own wellbeing. Such limited opportunities to disconnect from schoolwork, engage in physical fitness, rest, relax, and socialize with others can have serious implications for the long-term physical and mental health of women law students.

For more in-depth analysis about gender disparities in legal education, you can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website or contact us.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 3)

Opportunities for Improvement

Given the many challenges facing women upon entry to law school, it is no surprise that there are also opportunities to improve the experience for women students in legal education. LSSSE data on concepts as varied as classroom participation, caretaking, and debt make clear that women need greater support.

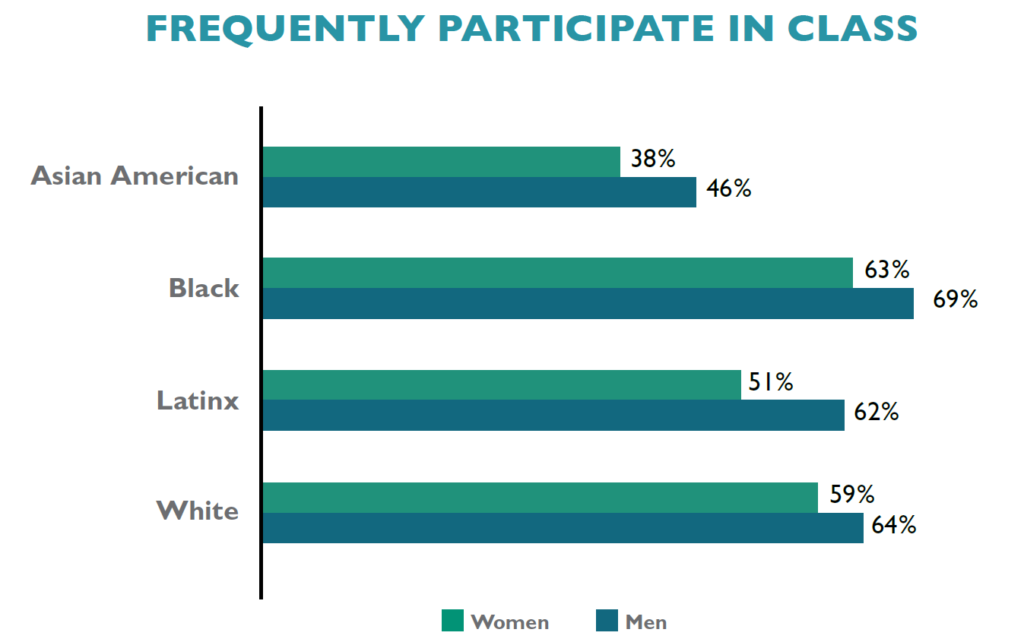

Engagement in campus life is an especially significant indicator of success. Law students who are deeply invested in both classroom and extracurricular activities tend to maximize opportunities for success overall. As stated in a previous post, women are just as likely as men to be involved in various co-curricular endeavors. Yet, smaller percentages of women than men are deeply engaged in the classroom. While 64% of men report that they “Often” or “Very Often” ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions, only 58% of women do. This gender disparity remains pronounced within every racial/ethnic group, as men participate in class at higher rates than women from their same background. There are also interesting variations by raceXgender, with Black men frequently participating at higher rates than any other group (69%), and at almost twice the rate of Asian American women (38%).

Many women students also spend numerous hours during their law school careers providing care to household members. For instance, 11% of women report that they spend more than 20 hours per week providing care for dependents living with them, as do 8.6% of men. These competing responsibilities require a significant investment of time, which could otherwise be spent on studying for class, working with faculty on a project outside of class, or even engaging in leisure activities. Instead, these students are taking care of their families.

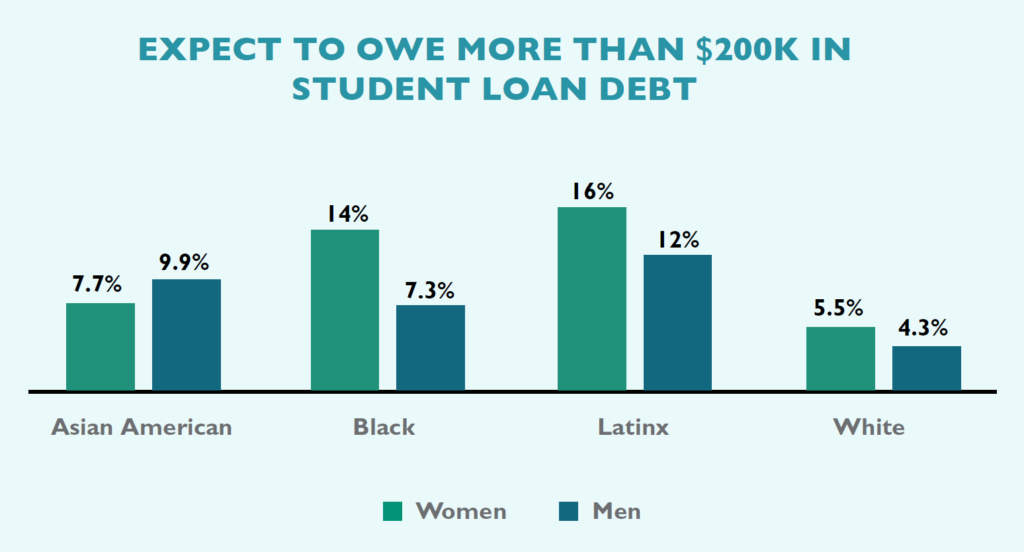

An especially troubling discovery is that high percentages of women than men incur significant levels of debt in law school. Among those who expect to graduate from law school with over $160,000 in debt are 19% of women and 14% of men. This gender difference remains constant within every racial/ethnic group. Even more alarming is the disparity among those carrying the highest debt loads: 7.9% of women will graduate from law school owing over $200,000 as compared to 5.5% of men. LSSSE data not only confirm existing research on racial disparities in educational debt, with people of color and especially Black and Latinx students borrowing more than their peers to pay for law school, but also reveal that women carry a disproportionate share of the debt load as compared to men. Furthermore, when considering the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, we see that women of color specifically are graduating with extreme debt burdens.

Next week, we will conclude this series with some troubling trade-offs that women make to overcome the disadvantaged position in which they often find themselves relative to their male counterparts. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 2)

Contextualizing Women’s Success

Women’s relative success in law school is quite significant when we consider basic demographic differences between women and men when they first enroll in law school. Fewer economic resources and lower test scores do not seem to inhibit women from achieving at high levels once on campus.

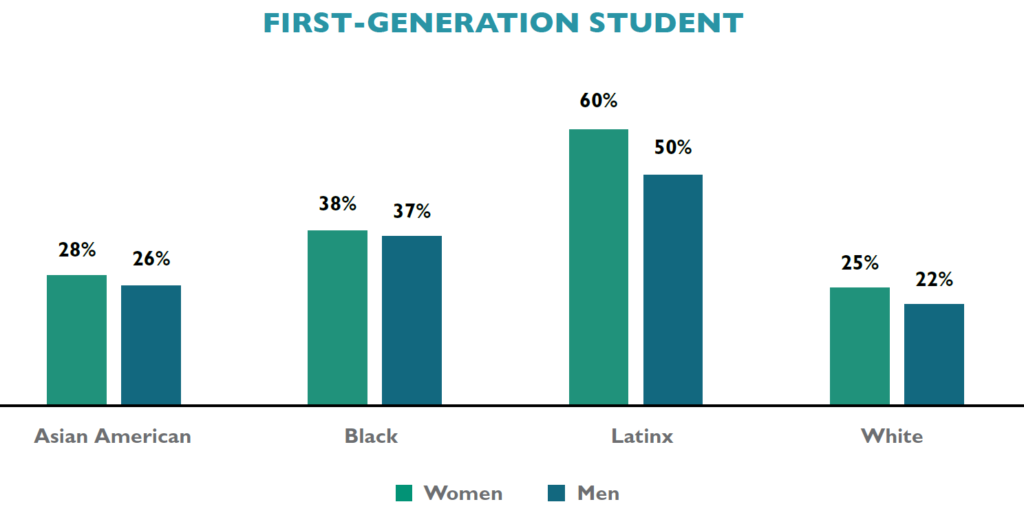

Parental education is a common proxy not only for family income but for future educational success, with the children of highly educated parents generally drawing on class privilege and extra resources to achieve at high levels. LSSSE data reveal that women are more likely than men to be first-generation law students, with 30% reporting that neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree as compared to 25% of male law students. This finding is consistent for women regardless of race/ethnicity, with Asian American, Black, Latinx, and White women being more likely than men from those same backgrounds to be the children of parents who did not earn at least a college degree.

Even considering those whose parents are highly educated, women law students are less likely than men to have a parent who is a lawyer. Among those reporting that they have a parent who earned a doctoral or professional degree, 57% of men but only 52% of women report that their parent’s degree is a J.D. Only Asian American women are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic background to have a parent with a law degree; higher percentages of male law students who are Black, Latinx, or White have a lawyer parent than women from those same backgrounds.

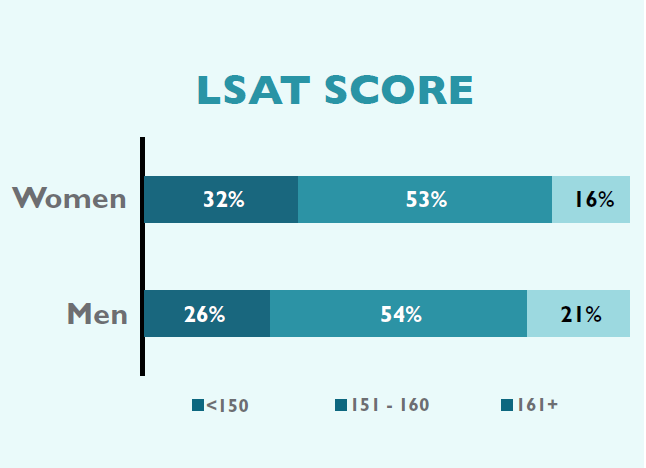

In addition to demographic differences based on parental status, women also report lower LSAT scores than men, even when comparing within racial/ethnic groups. While 21% of men report LSAT scores in the highest range of 161 or above, only 16% of women report similar achievement on this exam. This finding mirrors other critiques of high-stakes testing as potentially limiting opportunities for non-traditional students including women and people of color.

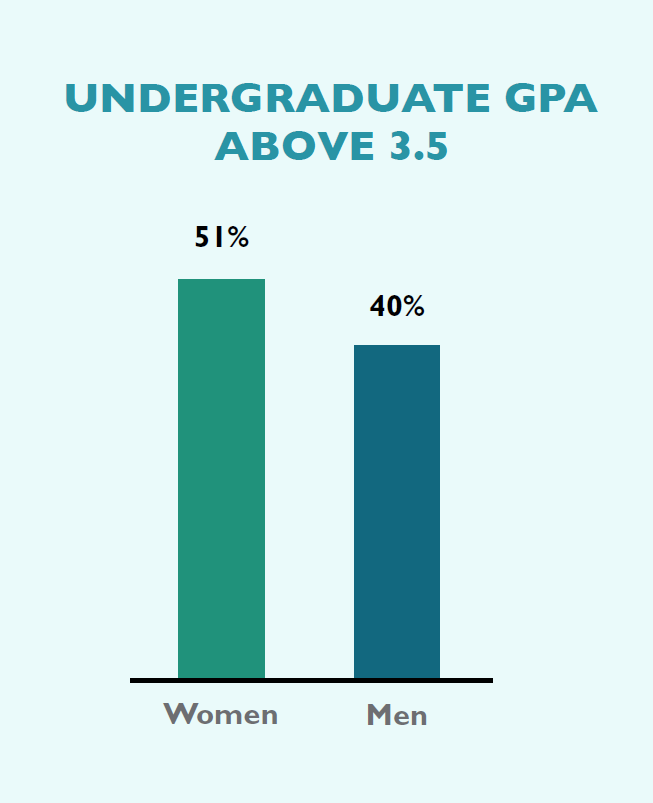

Conversely, higher percentages of women than men enter law school with undergraduate grade point averages (UGPAs) in the top range. A full 51% of women report UGPAs of 3.5 and above as compared to only 40% of their male classmates. As with LSAT scores, this gender finding is consistent across race/ethnicity: when comparing women and men from the same background, women outperform men on UGPA. Recall that in spite of the inconsistency of lower LSAT scores and higher UGPAs, women nevertheless report slightly higher overall law school grades than men. This may further bolster research questioning the value of using test performance as the primary determinant of expected success in law school and beyond.

The next post in this series will offer some opportunities for improvement in gender equity in legal education. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 1)

The past two decades have seen increasing numbers of women in law schools. After graduating from law school, women lawyers enjoy greater opportunities for financial independence, security of employment, and a potential for leadership facilitated by the J.D. degree. Yet, gender inequities in pay and position continue to plague the legal profession. In spite of this conundrum, there has been little scholarly attention given to the experience of women while in law school.

The 2019 LSSSE Annual Results celebrate women. We investigate the successes of women law students—using objective and subjective measures to reveal various accomplishments. We also interrogate their backgrounds and the context for their enrollment in law school, revealing challenges women overcome and the sacrifices they make to succeed. This Report not only shares findings on women as a whole, but also features comparisons by gender and race/ethnicity, providing greater depth and context to the overall experience of women law students. Our findings make clear that women’s success comes at great personal and financial cost. Greater awareness of these challenges provides both an imperative and an opportunity for administrators, institutions, and leaders in legal education to invest more deeply in the success of women.

The Good News

Women are succeeding in legal education along numerous metrics. When considering overall satisfaction rates, roughly equal percentages of women (81%) and men (83%) report that their entire experience in law school has been either “Good” or “Excellent.” In spite of generally high marks for all groups, there are notable differences by race/ethnicity. While the vast majority (75%) of Black women characterize their overall experience as positive, these rates are lower than those of women who are Asian American (78%), Latina (78%), and White (84%).

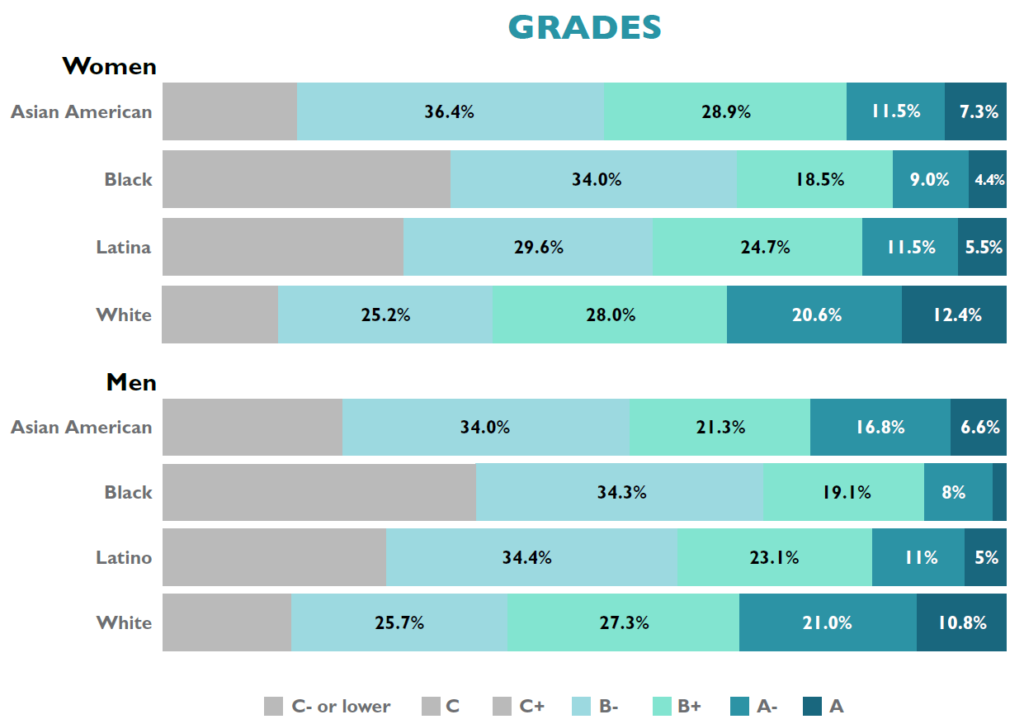

In addition to appreciating their law school experience, women are also excelling academically. Women’s self-reported law school grades are slightly higher than men’s. As one example 10.3% of women report earning mostly A grades in law school compared to 9.5% of men. There is important variation not only by race but also by the intersectional consideration of raceXgender. To start, 7.3% of Asian American women, 4.4% of Black women, and 5.5% of Latinas claim mostly A grades as compared to 12% of White women law students. Yet, when investigating grades within each racial/ethnic group by gender, women are nevertheless outperforming men.

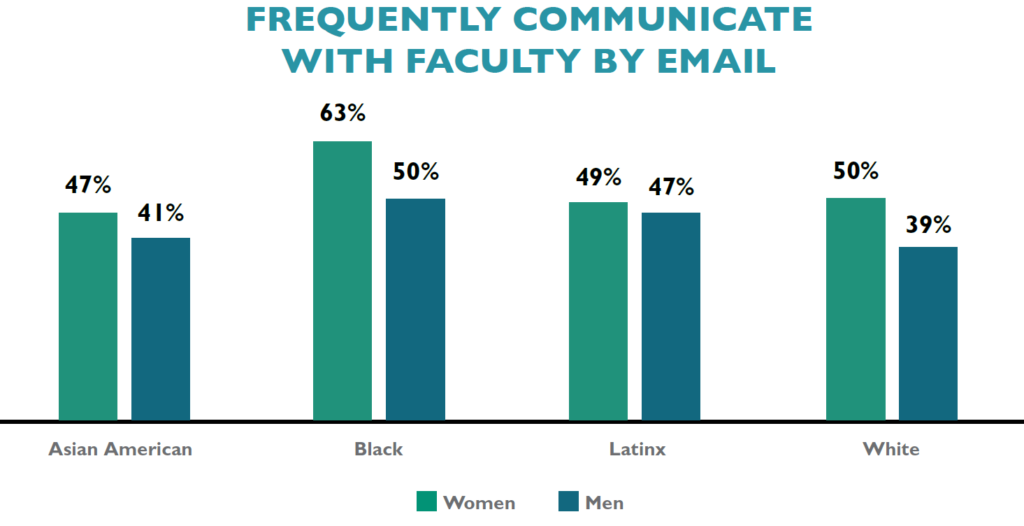

Additionally, women are adept at utilizing particular resources in law school, connecting with faculty and fellow students. Just over half (51%) of women use email to communicate with a faculty member “Very often” compared to only 40% of men. In fact, at 63%, Black women are more likely to engage in frequent email contact with faculty than any other raceXgender group. Women, regardless of their racial/ethnic background, are also more likely than men on average to engage in ongoing and frequent conversations with faculty and other advisors about career plans or job search activities. Women and men are also engaged in co-curricular activities at roughly equivalent rates, including the percentages participating in pro bono service, moot court, and law journals. A majority of students also enjoy positive interactions with classmates. A full 79% of men and 75% of women report the quality of their relationships with peers as a five or higher on a six-point scale. Furthermore, 65% of women rely on and invest in membership in law student organizations—which research has shown provide social, emotional, cultural, and intellectual support for many students. Black women (68%), Latinas (65%), Asian American women (60%), and White women (65%) join student groups at higher rates than men as a whole (53%).

Women are clearly engaged members of the law school community. Our next post in this series will discuss contextual differences between men and women before entering law school that suggest women are more likely to have to overcome obstacles to be successful. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

Guest Post: LSSSE Data Illustrates Public Service Intent Among Asian American Law Students

Aryssa Ham

Undergraduate Researcher

University of California, Davis

Public Service Intent Among Asian American Law Students

What drives people to set aside their personal interests to help the collective? In 2017, Yale Law School and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association found that Asian Americans gravitate towards careers in law firms and business over the public sector more than any other racial group, with few Asian Americans citing a desire to enter government as motivation to attend law school (Chung et al. 2017). Prior studies on the underrepresentation of racial minorities within the legal field often point to lack of academic or financial support as barriers to public service; yet Asian Americans were found to be the highest earning racial group in the U.S. and were overrepresented in top law schools (Sabharwal & Geva-May 2013; Kochhar & Cilluffo 2018; Chung et al. 2017).

This prompts a string of questions: Why are Asian Americans drawn to the private sector of the legal field? Why are they underrepresented in government and public interest? Alternatively, do Asian Americans prefer other forms of public service, such as pro bono work? If so, why doesn’t any other racial group appear to parallel this preference?

Despite past studies noting a weaker interest in the public sector among Asian Americans, few delve into potential explanations or examine variances among ethnicity. The original rallying, pan-ethnic Asian American identity has become a racial label that eclipses meaningful differences, propagating the Model Minority stereotype (Wu 2014:246). This social construct manifests in overlooked outcome disparities within the Asian American community, thus making ethnicity especially critical to examine.

As an undergraduate studying both psychology and sociology, I began an honors thesis last summer that integrates my majors: taking career decisions—a private, subjective experience—and zooming out to explore how these decisions interact with how society is organized and maintained. In my thesis, I study the professional trajectories of Asian Americans within the legal field—particularly the factors that determine whether and when an individual enters, stays, or switches into the public or private sector. Ultimately, I aim to shed light on why the legal profession is an underused entryway into government for Asian Americans, while simultaneously revealing the contrasting stories that vary by ethnicity.

Why LSSSE data?

I examine the extracurricular activities of law students to uncover patterns among students exhibiting public service motivation before fully entering the legal field. Although students can enter law school at different points in their life, I treat law school extracurriculars as the first major professional fork between the public and private sector.

While LSSSE data on student pro bono experiences are publicly accessible, ethnicity data are not shared on the website. After reaching out to Professor Meera Deo and LSSSE, they graciously provided the 2019 analyses that I needed.

I looked at 3 LSSSE Questions:

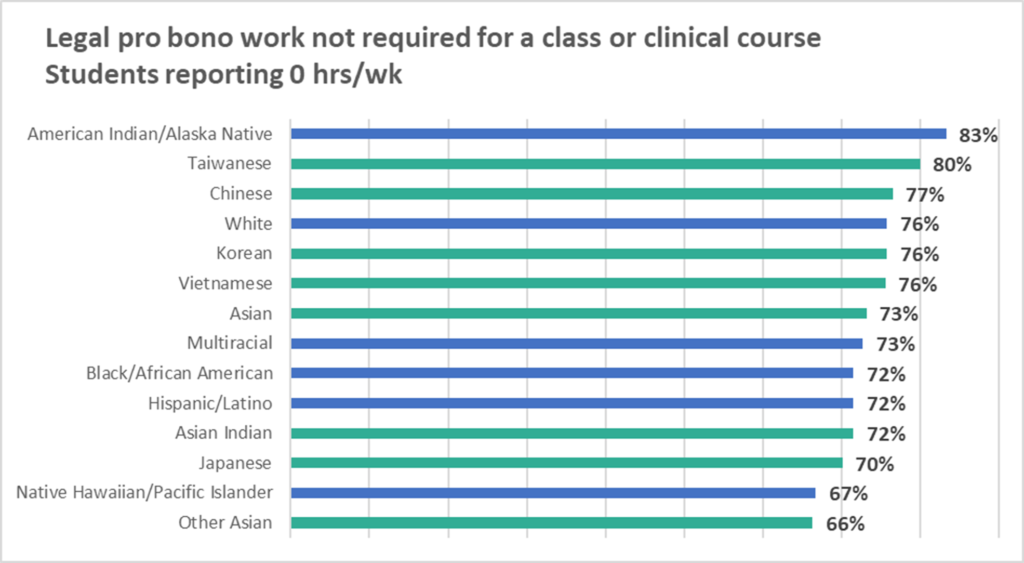

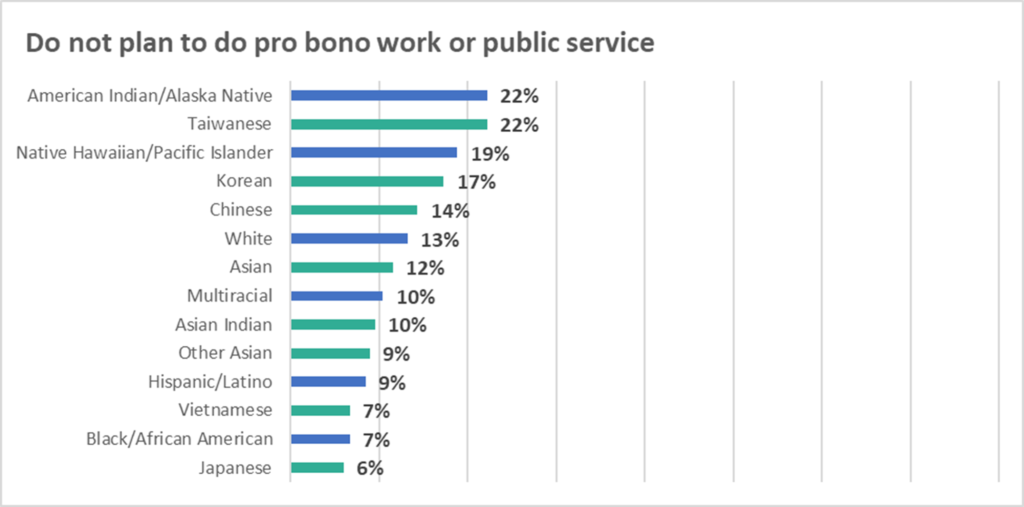

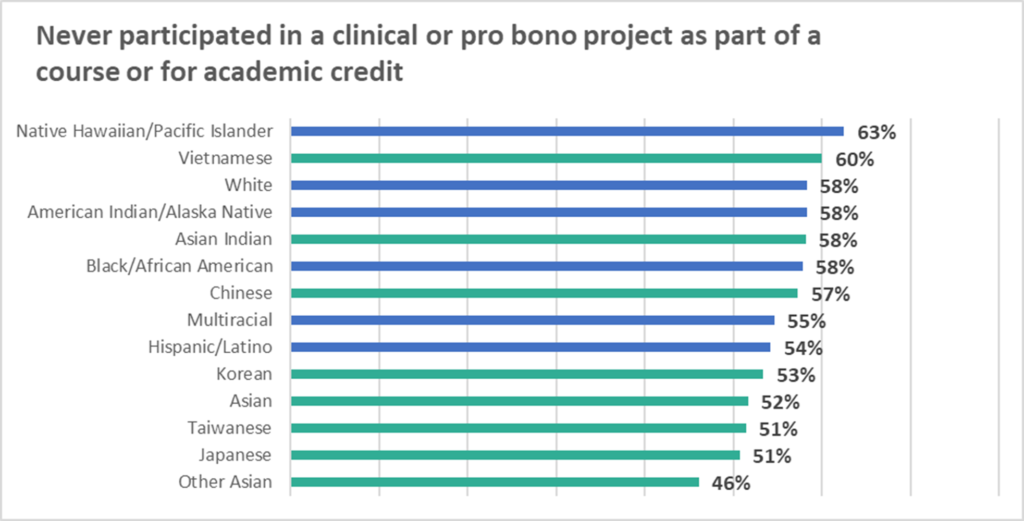

The first question (Pro Bono) asked for the number of hours a student spends each week doing legal pro bono work not required for a class or clinical course. The second (Public Service) asks if a student has done or plans to do pro bono work or public service before graduation, with response options "undecided," "do not plan to do," "plan to do," or "done." The final question (Clinical Project) asks how often a student has participated in a clinical or pro bono project as part of a course or for academic credit, with response options ranging from "never" to "very often."

Here’s what I found:

Pro Bono: Asian ethnicities with greater proportions of participation in pro bono work tend to be those with higher than national median incomes and better representation as elected officials, with four Japanese Americans and five Asian Indian Americans currently holding office in U.S. Congress, while other Asian ethnicities, such as Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, or Vietnamese American, include one to two representatives, if at all. Other Asian, Japanese, and Asian Indian have the lowest proportion of students responding with "0 hours/week."

Public Service: While this question tracks progress from 1L to 3L, the graph echoes the results of Pro Bono, with Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese American students being the only Asian ethnic groups with a higher proportion of “do not plan to do” than white students.

Clinical Project: The proportion of Asian Americans who have participated is the highest among all races. When broken down by ethnicity, Other Asian, Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean American have the lowest proportion of “never” responses. On the other end, proportions of Asian Indian Americans reporting “never” (58.2%) most closely mirrors those of white students (58.3%). Finally, Vietnamese Americans have the highest proportion aside from Hawaiian/Pacific Islander reporting “never,” but they also have the second-highest proportion reporting “very often,” only behind Other Asian.

Note: The “Other Asian” label is large, with a sample size more than doubling three of the six other reported Asian ethnicities. Ideally, a Filipino category would have been useful among the ethnic breakdowns, as Filipino Americans constitute the third largest proportion of Asian Americans.

Main Takeaway

The findings reiterate how the Model Minority stereotype harmfully obscures the needs of many Asian Americans. Although the proportion of Asian Americans who contribute pro bono work is lower than other racial minorities and higher than white students, Asian ethnicities with fewer structural constraints (e.g., higher national median income, greater government representation) contribute a greater proportion of pro bono hours than Black and Latinx students, leaving students of other Asian ethnicities potentially overlooked or under-supported.

This concludes the survey portion of my thesis. To complement the survey data, I am conducting interviews with Asian American lawyers in both the public and private sectors. I hope to code the transcripts for potential public service motivation factors, uncover individual attitudes toward the public sector, and fully explore the linear and nonlinear paths of Asian Americans in law.

Huge thanks to Professor Deo and the LSSSE staff for being incredibly helpful! As an undergrad, I was astonished at how willing they were to accommodate me, and I’m so grateful for their support.

Finally, if anything piqued your interest, please don’t hesitate to contact me at aham@ucdavis.edu.

References

Chung, Eric, Samuel Dong, Xiaonan April Hu, Christine Kwon and Goodwin Liu, Yale Law School & National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, A Portrait of Asian Americans in the Law (2017).

Kochhar, Rakesh, and Anthony Cilluffo. “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians.” Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 12 Jul. 2018, www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/.

Sabharwal, Meghna and Iris Geva-May, “Advancing Underrepresented Populations in the Public Sector: Approaches and Practices in the Instructional Pipeline.” Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19:4, 2013, 657-679, DOI: 10.1080/15236803.2013.12001758

"U.S. Asians Have a Wide Range of Income Levels." Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 8 Sept. 2017, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/ft_17-09-08_asian_income/.

Guest Post: What LSSSE Data Can Teach Us About Developing Our Law Students for Influence and Impact as Leaders

Leah Teague

Leah Teague

Chair, AALS Section for Leadership

Associate Dean and Professor, Baylor Law School

Leah_Teague@baylor.edu

https://traininglawyersasleaders.org/

In legal education we brag about the leadership positions our graduates hold. We tell our current students they too will be leaders someday. We expect that of them. But what are law schools doing to prepare students for those roles? You might be surprised to know that we do very little in law school to intentionally develop students’ leadership acumen and skills.

One might argue that all of legal education is training for leadership. Lawyers routinely use skills developed in law schools (such as critical thinking, legal analysis and advocacy) to help others. Attorneys also serve others by strategizing, persuading, and ultimately commanding the room, whether it be the boardroom, courtroom, or public arena. These are all foundational leadership skills. So why aren’t we being more intentional about preparing our students for the leadership roles we know they will someday assume?

Perhaps more importantly, why aren’t we teaching our students about the critical leadership roles played by lawyers throughout history and the urgent need for us to continue to do so? With precious little time spent in law school on the role of lawyers in society and increasing emphasis on law as a business and lawyers as legal technicians and specialists, fewer students leave law school with an understanding of our role as protectors of the rule of law, seekers of justice, wise counselors to individuals and businesses, and effective community leaders. While understandable, considering the economic and other competing pressures on lawyers’ time today, but how ironic – and concerning – considering that the majority of law school applicants still state in their personal statements their desire to go to law school to do good – to right wrongs, stand up for those without voice or power, or to make a difference in society.

Lawyers are small in numbers. We are less than one-half of one percent of the population in America. Yet, we are still mighty in impact and influence. But that might not continue. Some are concerned that our influence is already waning. For example, in the mid-19th century, almost 80% of members of U.S. Congress were lawyers. By the 1960s this dropped to under 60%. Currently, it is about 40%. Does having fewer leaders trained and experienced in strategic planning, advocacy, negotiation and civil discourse make a difference? Don’t we need more decision-makers at all levels who are trained in the law and who understand our obligation to society as guardians of democracy?

The question for us as legal educators is how do we better prepare our students for these important roles? To address this important issue, a new Section for Leadership was approved by the American Association of Law Schools. Our section reached out to Meera Deo and Chad Christensen at LSSSE to look at what we can learn from data already being collected by LSSSE. Chad shared his thoughts and findings during a webinar on November 5, 2019.

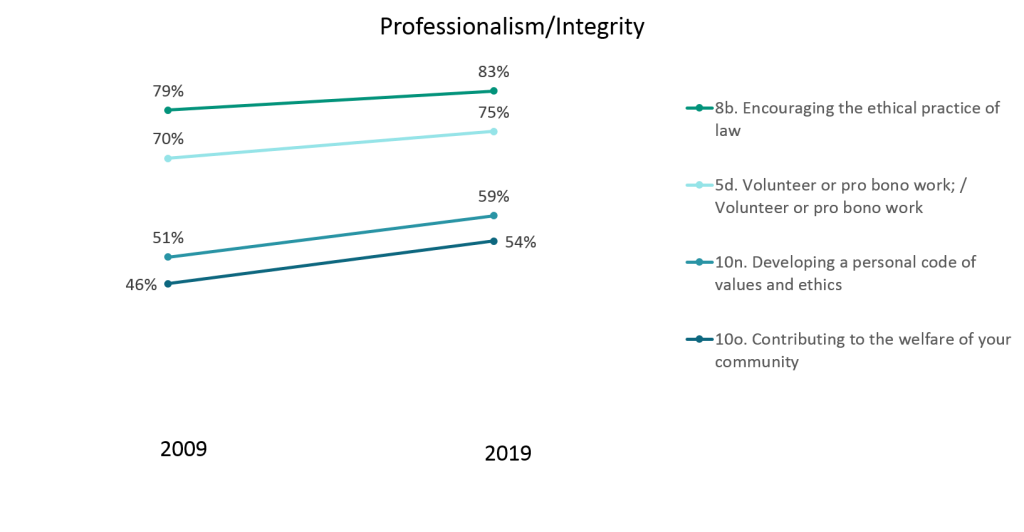

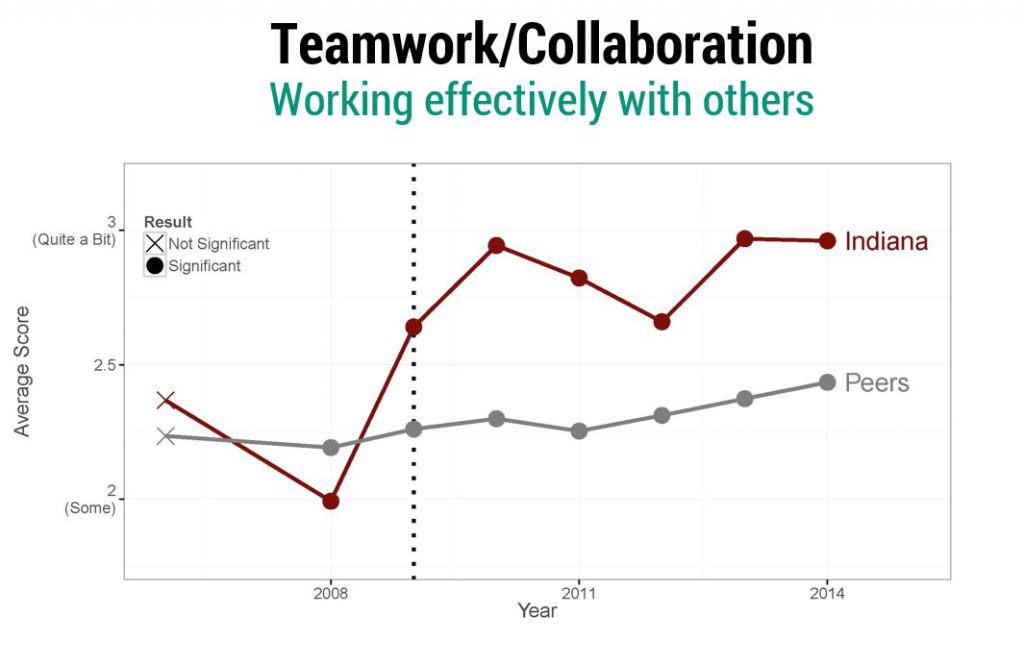

Chad began with an overview of work being done at the Holloran Center and others to look at professional competencies touted by a series of reports (such as MacCrate and Carnegie), desired by legal employers, and now mandated by ABA Standards 302(c) and (d). Many of these professional competencies are attributes of leadership and are included in the annual LSSSE instrument, including teamwork and collaboration, professionalism and integrity, self-directedness and cultural competencies. Chad shared the specific LSSSE questions related to these attributes and discussed the findings related to those questions from 2009 to 2019. The good news is that Chad’s charts showed improvement over time in almost all of those questions. (You can view the specifics of the LSSSE questions and the results related to these leadership attributes by downloading the Webinar Slides.)

Even more exciting was the example he shared of LSSSE in action. In 2008, Indiana University (IU) 1Ls reported a significantly lower level of teamwork/collaboration than 1Ls at its peer schools. After introducing a first-year, legal professions course in 2009 that emphasized a goal-oriented, collaborative approach to legal work, IU experienced a significant improvement in that category.

We believe the work at a growing number of law schools to introduce leadership development into their programming and curriculum not only will benefit students but also our profession and society. With that said, we are still figuring out how to be most effective and where to focus our efforts. We agree that the goal is to teach our students about the critical role lawyers play in society and our obligation as lawyers to serve, and then to better prepare them for the many opportunities they will have to serve. We want to help our students develop skills and traits that not only will enable them to be more effective in their professional roles but also will better equip them to make a meaningful difference in the lives of the individuals and organizations they serve. We also know that when they do so they will experience the kind of meaningful fulfillment that leads to satisfaction, contentment and happiness. Don’t we all want that for our students? For ourselves?

We believe the work at a growing number of law schools to introduce leadership development into their programming and curriculum not only will benefit students but also our profession and society. With that said, we are still figuring out how to be most effective and where to focus our efforts. We agree that the goal is to teach our students about the critical role lawyers play in society and our obligation as lawyers to serve, and then to better prepare them for the many opportunities they will have to serve. We want to help our students develop skills and traits that not only will enable them to be more effective in their professional roles but also will better equip them to make a meaningful difference in the lives of the individuals and organizations they serve. We also know that when they do so they will experience the kind of meaningful fulfillment that leads to satisfaction, contentment and happiness. Don’t we all want that for our students? For ourselves?

Our thanks to our co-sponsors for the webinar, LSSSE, AALS Section for Empirical Studies of Legal Education and the Legal Profession, and AALS Section on Law and the Social Sciences. We were excited to find more kindred spirits in our work! Our special thanks to Chad for his personal and vested interest in leadership development for lawyers. We look forward to further collaborations!

We invite all who are interested in introducing or expanding leadership development for law students at your school to join us. Feel free to contact me for more information at Leah_Teague@baylor.edu.

Guest Post: Student Engagement and Law School Stress

Gary R. Pike, Ph.D.

Gary R. Pike, Ph.D.

Professor, Higher Education & Student Affairs

Indiana University

The opening scenes of the 1973 movie The Paper Chase show Professor Charles Kingsfield (played by John Houseman) sternly questioning his first-year students about the fine points of case law. Professor Kingsfield’s questioning is so intense that one student becomes physically ill. Although The Paper Chase is a work of fiction, the stress of trying to be a success in law school is very real. In her Huffington Post article, Kate Mayer Mangan reported that 96% of all law students experience high levels of stress, a rate that is much higher than rates for medical school and other graduate students. According to Mangan, law school stress appears to be a product of workload and the teaching methods used in most law schools—case-diaogue instruction. Research I just conducted using data from the 2015, 2016, and 2017 LSSSE administrations showed that law school stress played an important role in what students learn.

Stress in Law School

Stress in law school was greatest for first-year students, first-generation students, women, Latinx, and Asian American students. The amount of debt incurred in law school also increased law school stress. Likewise, students’ effort in their courses increased stress, but the extent to which students felt supported in law school reduced stress.

Student Engagement, Stress, and Learning

A goal of my research was to examine the relationships among student engagement, stress, and learning during law school. I found that both the effort students put forth in their courses and the extent to which students feel supported in law school were strongly related to both academic and personal/social gains. This finding is consistent with the findings of the National Institute of Education’s Study Group on Excellence in American Higher Education report Involvement in Learning, which concluded that both setting high standards and supporting students are necessary for student success. Law school stress had a negative effect on academic learning gains, although it was not related to personal/social learning outcomes.

Gender Differences

I also found that the relationships among student engagement, stress, and learning gains differed for males and females. First and foremost, stress had a much stronger negative effect on academic outcomes for women, compared to me. This is a serious concern because women reported significantly higher levels of stress than men. On a positive note, a supportive environment in law school tended to have a stronger effect for women than men on reducing the negative effects of stress on academic gains.

Conclusion

In sum, my research shows that stress is a serious concern in law school, particularly during the first year. Stress tends to be greatest for underrepresented groups in law school—women, first-generation students, as well as several racial/ethnic minority groups. Law school deans and other administrators and faculty members who are interested in reducing stress and reducing the negative effect of stress should focus on creating supportive environments in law school, particularly for women and minoritized groups.

____

References

Mangan, K. M. (2014, October 28). Law school quadruples the chances of depression for tens of thousands: Some changes that might help. Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/kate-mayer-mangan/law-school-quadruples-dep_b_5713337.html.

National Institute of Education Study Group on the Conditions of Excellence in American Higher Education. (1984, October). Involvement in learning: Realizing the potential of American higher education. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. ERIC Document Reproduction Service, ED246833.

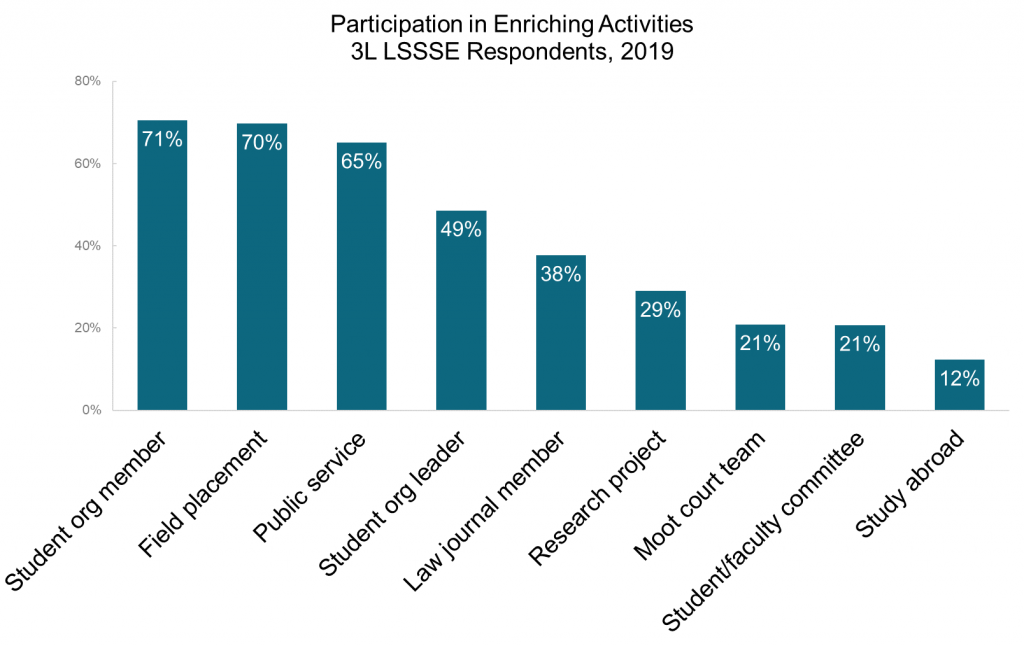

Enriching Experiences: Expectations and Reality

Participation in enriching activities can help law students gain experience, learn new skills, and forge professional connections. LSSSE is a powerful tool for measuring student engagement both inside and outside the classroom. Using 2019 LSSSE data, we know that most students had joined at least one student organization (71%), completed a field placement (70%), and engaged in public service (65%) by the end of their third year. Relatively few students had competed on a moot court team (21%), served on a student/faculty committee (21%), or studied abroad (12%).

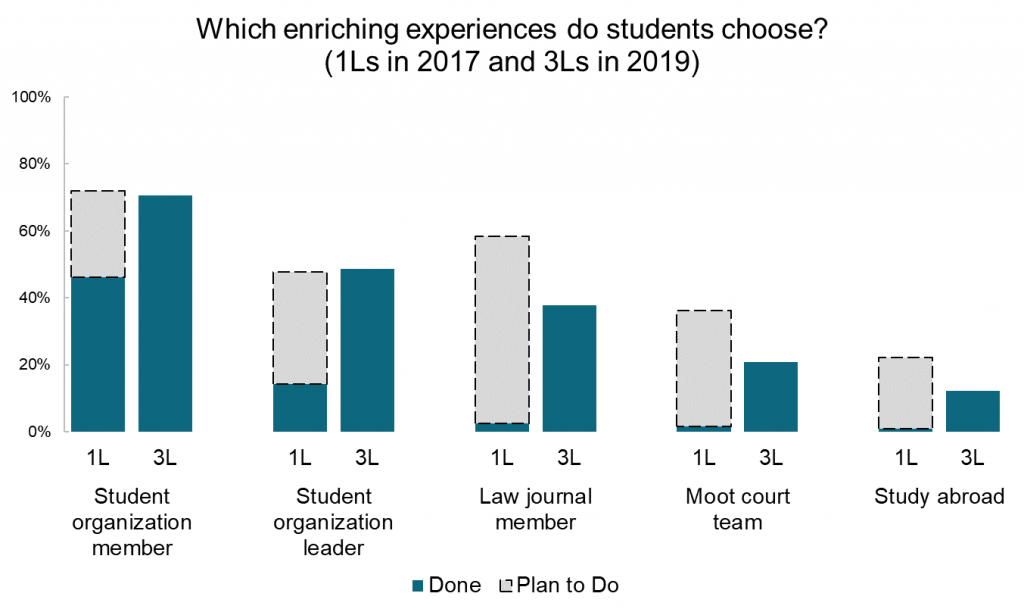

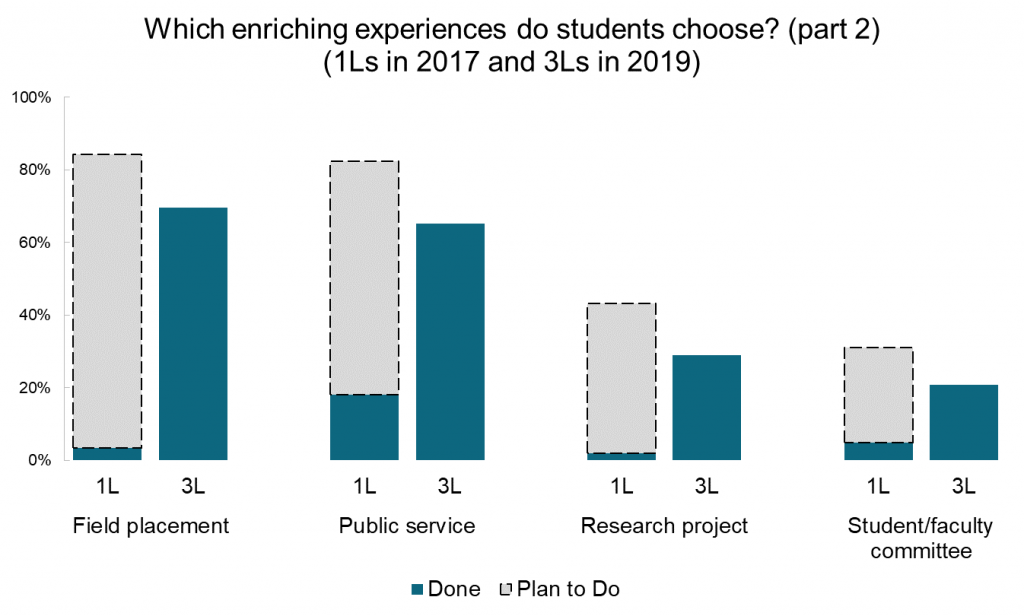

But how do 1L students’ intentions to engage in enriching experiences match their experiences? We compared the 1L student data from 2017 with 3L student data from 2019 to see whether students in this cohort had ultimately engaged in the activities that seemed most appealing early in their law school careers.

Nearly half (46%) of student had joined at least one student organization by the end of their first year, and another 26% planned to do so eventually (72% total). Indeed, by 2019, 71% of students had become a member of a student organization. The expectations and reality were similarly matched for student organization leadership, with 14% serving in a leadership position during their first year and another 34% planning to take on a leadership role eventually (48% total). In 2019, 49% of students reported having been a student organization leader. However, approximately a third of students expected to work on a law journal, but only 20% of students had been law journal members by the time they became 3Ls.

Gaining real-world legal experience was a high priority for 1L students, with 84% of 1Ls expressing interest in field placements and 82% expressing interest in public service. Most students engage in these experiences before graduation (70% and 65%, respectively). Less than half of 1L students express interest in research projects (43%) or student/faculty committees (31%), and even fewer go on to participate in these activities (29% and 21%, respectively).

As one might expect, different activities have different levels of appeal for students. But in general, 1L student seem to accurately predict where they will devote their extracurricular energy over the course of their law school careers.

Guest Post: Connecting Bar Exam Performance to the Law Student Experience

Aaron N. Taylor

Executive Director

AccessLex Center for Legal Education Excellence

There is much research tying student engagement to academic performance. The more engaged students are, the better their academic outcomes. Little of this research, however, has been conducted in the law school context. This is a significant gap in information, particularly given the extent to which law schools must focus on outcomes, such as bar exam passage rates.

AccessLex Institute aims to fill this gap with an upcoming report summarizing our work with the AccessLex/LSSSE Bar Exam Success Initiative. The report—planned for release in Spring 2020—will present findings from analyses of factors that impact law school academic performance and first-time bar exam performance among graduates of 19 law schools that are participating in the initiative.

We considered a range of factors, including graduate demographic background; their undergraduate GPA and LSAT score; their law school grades; and responses that many of them provided on the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) in their third year. In all, we tested the marginal influence of over 60 engagement variables on law school grades and bar exam performance.

Understanding the factors that influence academic and bar exam outcomes can aid law schools in identifying high-impact experiences and interventions premised on student success. This insight could also help schools better design their admission processes in ways that properly contextualize admission factors and minimize overreliance on certain factors.

Across all 19 schools, measures of law school academic performance were the strongest predictors of bar exam performance. For the vast majority of schools, LSAT scores and undergraduate grades (UGPA) were partial predictors of law school academic performance. At the median level, a one-point increase in LSAT score was associated with a 0.07 increase in final law school GPA. At the median level, a one-tenth point increase in UGPA was associated with a 0.08 increase in final law school GPA (LGPA). The LSAT score had a statistically significant predictive relationship with final GPA at 18 of the 19 schools. The UGPA was tied to final GPA at 15 of the 19 schools.

The analyses also yielded interesting findings about relationships between different aspects of student engagement (as captured by LSSSE responses) and academic and bar exam performance overall and among the 19 schools. Below are three of the most notable. All of these findings yielded statistically significant relationships to final LGPA or bar exam outcome, even after controlling for the other factors in the model. Put simply, these factors were independently influential.

#1: Raise your hand if you’re……unsure.

The frequency of asking questions in class had a positive and statistically significant relationship to final LGPA. Students who reported asking questions “very often” in class had a predicted final LGPA of 3.25, while those who reported “never” asking questions in class had a predicted final LGPA of 3.18. Asking questions are a manifestation of engagement, and among the pool of students we studied, questions were associated with higher grades.

#2: Do the reading!

Unsurprisingly, coming to class unprepared was associated with lower grades. Students who reported coming to class unprepared “very often” had a predicted final LGPA that was 0.17 grade points lower than those who reported “never” coming to class unprepared. So, students: do the reading. Your grades really do depend on it.

#3: Student-faculty interaction matters

At nine of the 19 schools, the quality of relationships between students and faculty had a positive, statistically significant relationship to final GPA (the strongest predictor of bar exam outcome). Students who rated these relationships highly tended to have higher GPAs. Interactions with faculty members are central to the law student experience. How students view their professors – as teachers, as mentors, as sources of guidance and support – translates into more engagement and better outcomes.

Be on the lookout for our national report as well as a companion blog on this website providing a more in-depth discussion of key findings. This analysis will employ applied research principles and methods to provide participating schools with tangible, actionable information, including explanation and illustration of significant findings from the project and appropriate recommendations. If your law school would like to be a part of our initiatives involving student engagement and bar success, contact us at research@accesslex.org.