Meaningful Sources of Career Advice for Law Students

Navigating career decisions can be one of the most challenging aspects of law school, and many students find themselves seeking advice to chart their path forward. Whether considering judicial clerkships, corporate law roles, public interest positions, or alternative legal careers, law students often feel a mix of excitement and uncertainty. Balancing academic demands with the pressure to make strategic choices about internships, networking, and future goals requires careful planning. And the guidance of mentors, professors, and peers can make all the difference.

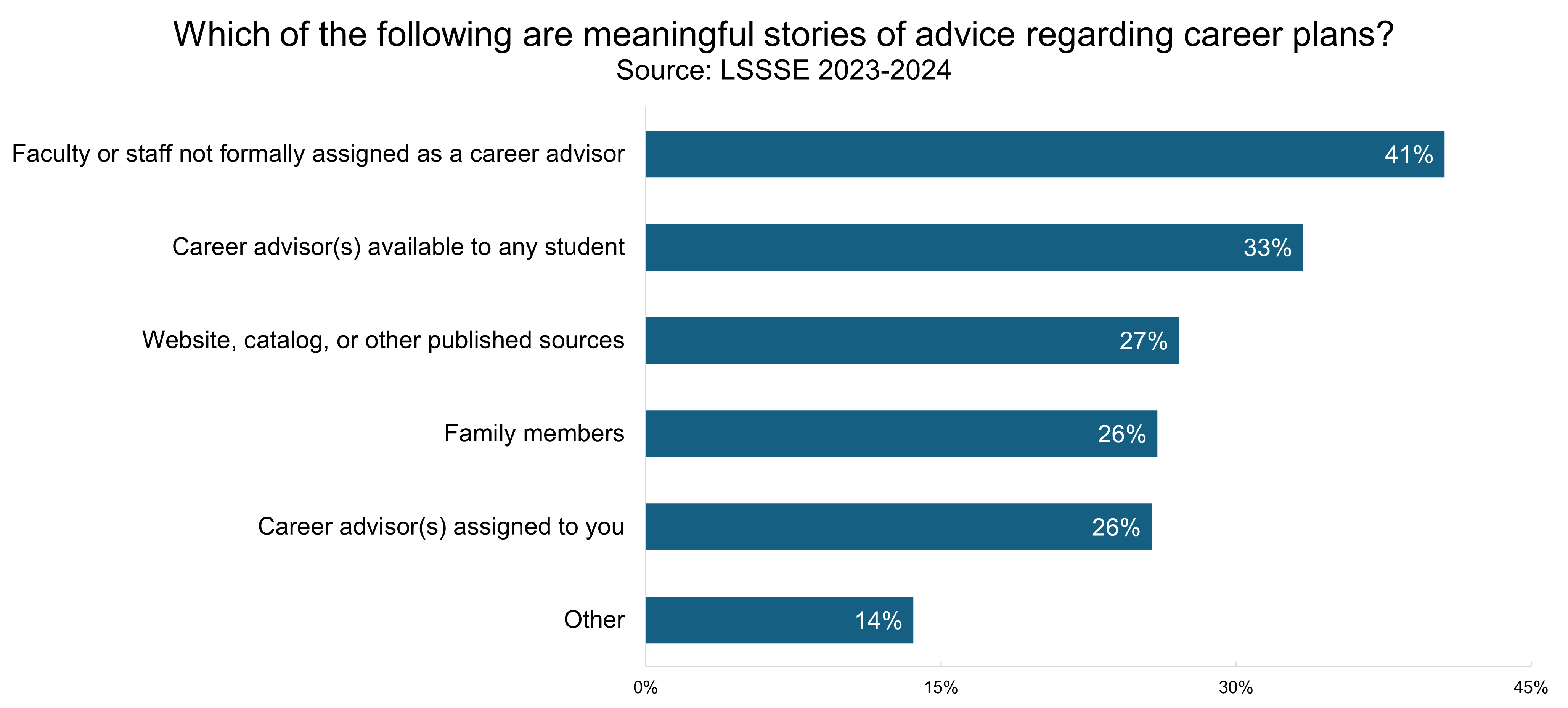

Using 2023-2024 data from the LSSSE Student Services module, we examined the meaningful sources of career advice that law students draw upon to help with professional preparation. Interestingly, law students are more likely to seek out career advice from faculty or staff members not formally assigned as career advisors rather than from formal career advisors at their law school. Only about a third of law students receive meaningful advice from careers advisors available to any student, and only about a quarter receive meaningful advice from a career advisor assigned to them, which is equal to the percentage of students receiving meaningful advice from family members (26%).

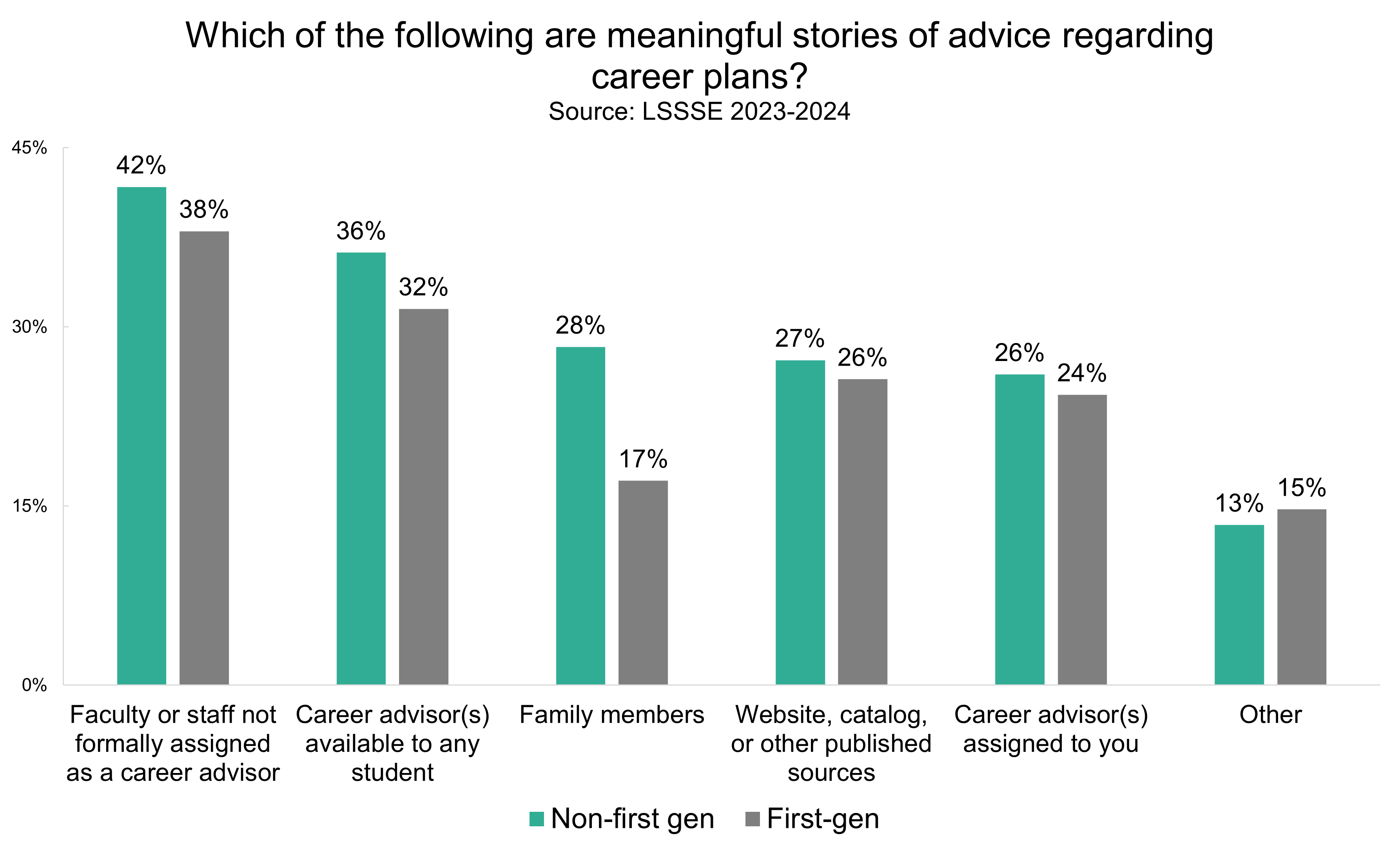

Given that family input will vary widely across different student backgrounds, we compared the sources of career advice for first-generation and non-first-generation law students. For first-generation law students (those who do not have a parent with at least a bachelor's degree), family members are much less likely to be a meaningful source of career advice. However, troublingly, first-generation students are also less likely to receive meaningful career advice from other sources relative to their non-first-generation peers. In other words, law schools may not be filling the gaps for first-generation students to support their transition into the legal profession.

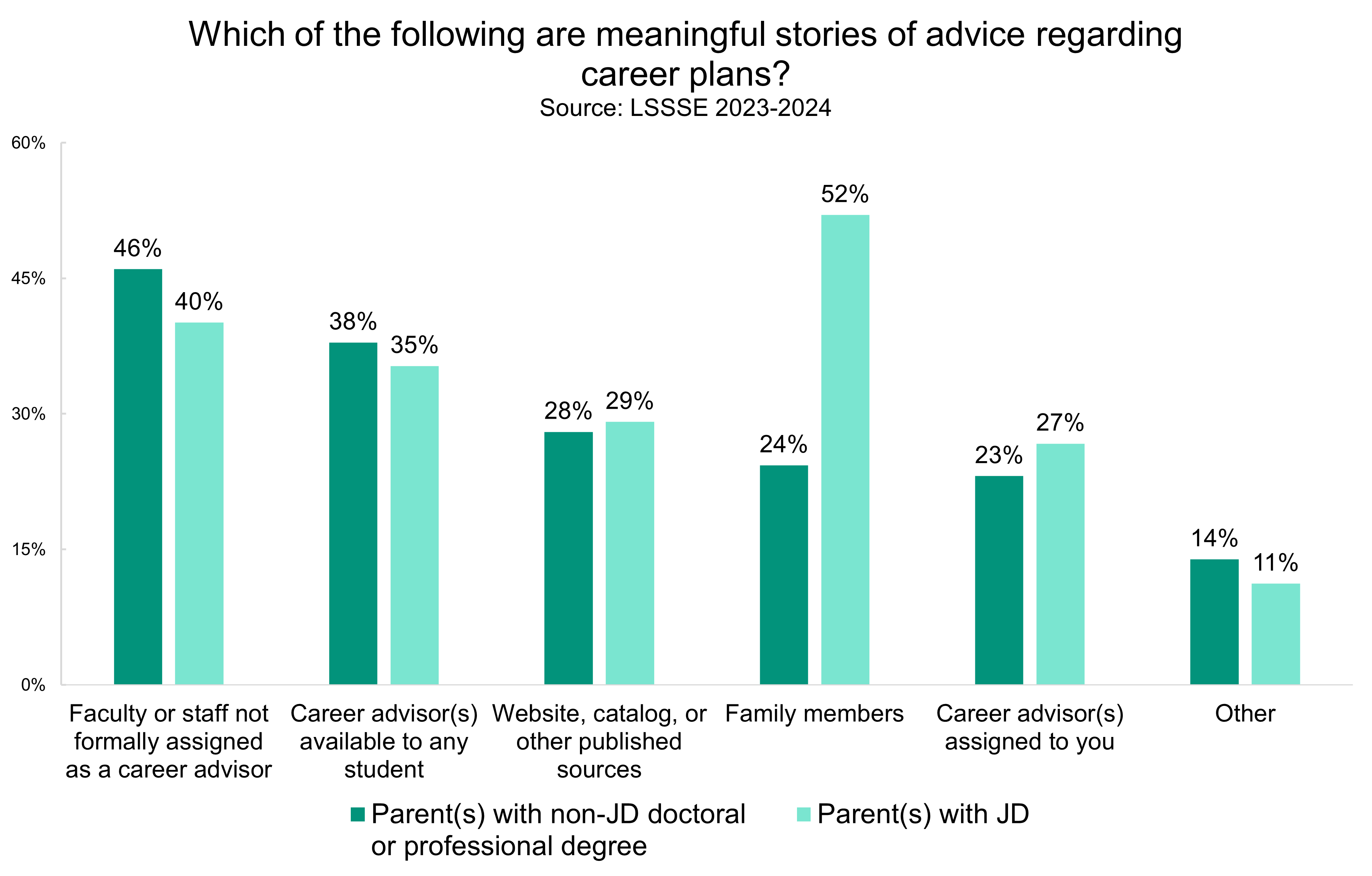

Digging deeper into the non-first-generation data, we wanted to know what impact having a parent with a law degree has on students’ sources of meaningful career advice. Among students who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree, we see, not surprisingly, that students who have a parent with a JD are more likely to cite family members as a meaningful source of career advice than students who have a parent with a non-JD doctoral or professional degree. However, only around half (52%) of law students who have a parent with a JD note that they are receiving meaningful career advice from a family member. The students with a JD-holding parent are a little more likely to get advice from career advisors assigned to them and a little less likely to receive advice from faculty, staff, or career advisors who are not formally assigned to them.

These findings highlight critical gaps and opportunities in how law schools support students in their career preparation. While informal networks and personal relationships with faculty or staff often play a vital role, the data suggest that formal career advising structures may not be as effective as they could be, particularly for first-generation students. Law schools should consider rethinking how they engage with students in career advising, ensuring that resources are accessible and tailored to meet the diverse needs of their student body. By strengthening these systems and bridging the advice gap, particularly for those from underrepresented backgrounds, law schools can better prepare all students for the challenges and opportunities of the legal profession.

The Parenting Penalty for Law Students

Laila L. Harris

Laila L. Harris

Associate Professor of Law & Co-Director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic

Associate Provost of International Affairs

Tulane University Law School

This fall, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory on the mental health and well-being of parents, responding to levels of high stress parents report and the harmful effects on their own mental health, as well as their children’s. This was on the heels of findings from a national study that a majority of parents experience isolation, loneliness and burnout related to parenting. For those of us at law schools, often recognized as high stress environments already, it raises the question: what is the landscape for parents in law schools?

Professor Lindsay M. Harris (University of San Francisco Law School) and I have begun talking and writing about “the parenting professor penalty,” the panoply of harms and challenges that pregnant and parenting people, as well as those who are presumed to become pregnant or parenting, face in entering and being successful as faculty within the legal academy. We are bringing this topic to the annual AALS meeting, focused on “Courage in Action” held in January as a discussion group session and welcome you to join us. Yet faculty often comprise those with the most privileged positions in law schools, relative to staff and students. Law students who are parents, or more broadly caretakers, may face steep challenges and inequities related to their status and circumstances.

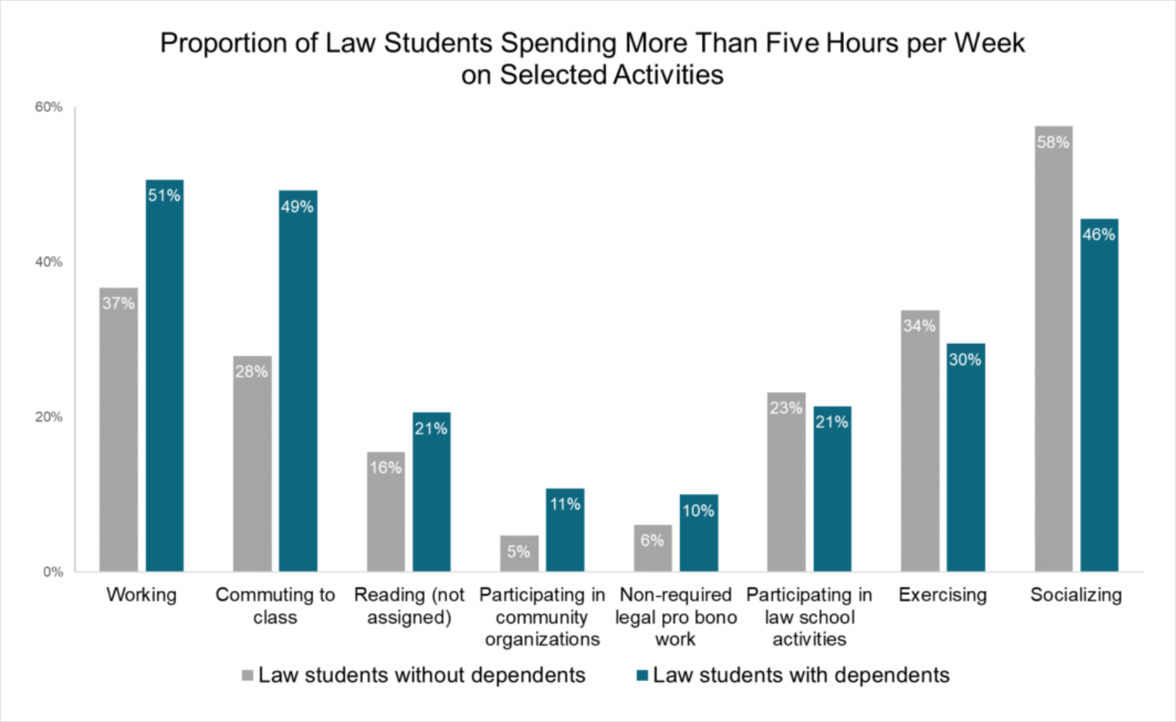

Mental health has long been a concern in law schools and the legal profession. According to LSSSE, around 60% of law students experience very high law-school related stress or anxiety. Law students who also serve as caretakers are particularly likely to have more stress. This is especially true because students with dependents also spend more time on commuting to class and working, and less time on exercising and socializing, which may help combating anxiety and isolation.

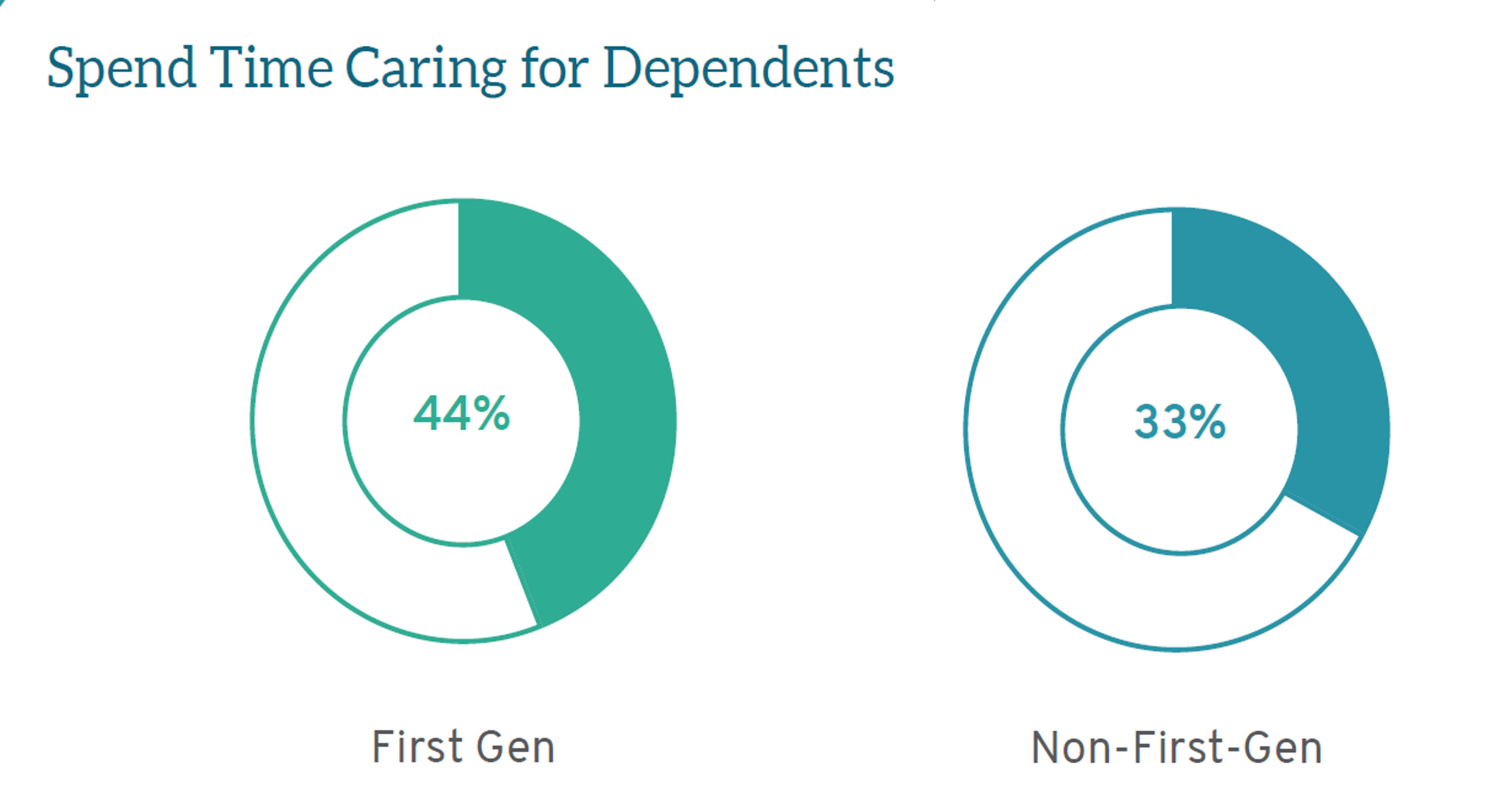

While about one-third of law students reported spending time caring for dependents, the burden of hours spent every week is particularly high for non-traditional law students. First-gen students comprise a larger portion of law student caretakers: 44% of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

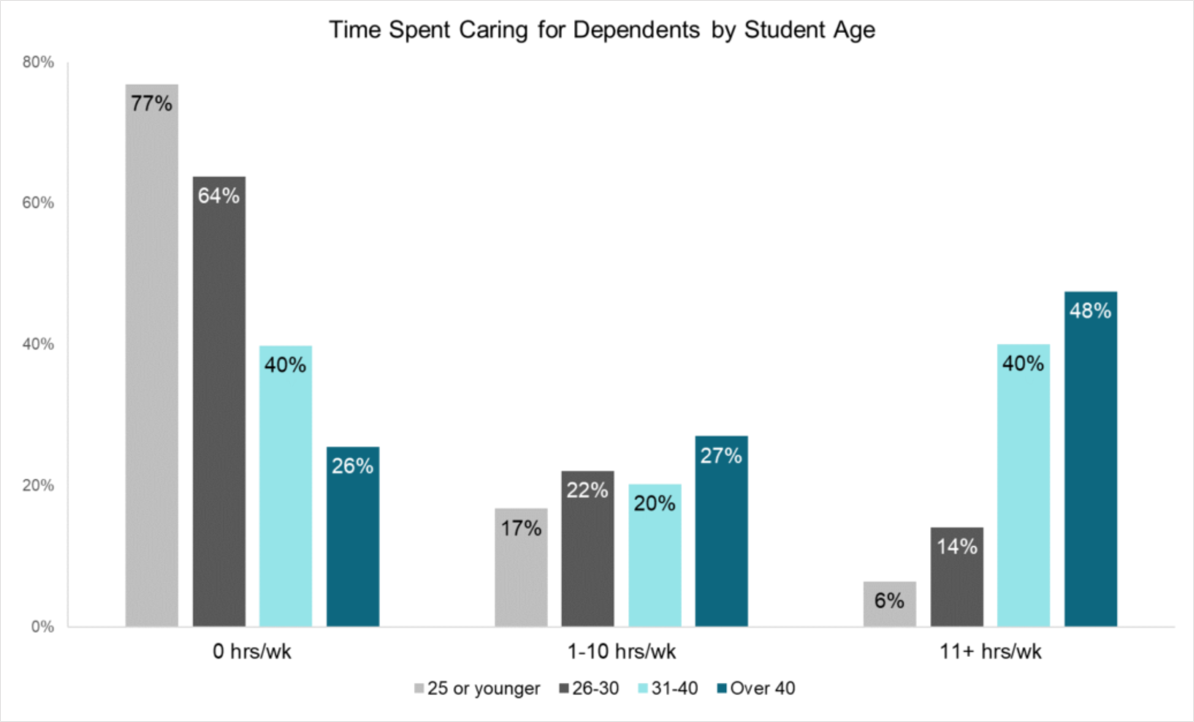

Caretakers are also over-represented in part-time law programs, with 56% of part-time students reporting caretaking for dependents. Time spent caretaking per week is highest for older law students, as 40% of those aged 31-40 spent 11 or more hours per week caretaking, and nearly half of those aged over 40 spent 11 or more hours caring for dependents.

Given these genuine concerns for law student caregivers, how can we as law faculty respond individually and collectively, and how can we respond institutionally as law schools?

As individual actors, law professors should think about how to account for the stresses parenting law students may be facing. Professor Harris and Professor Mallika Kaur recently released a co-edited volume titled How to Account for Trauma and Emotions in Law Teaching, which is instructive and helps to mainstream conversations about stress and well-being within law schools. Professors may, for example, want to think about whether they want to model “parenting loudly,” though this is not without varying consequences depending on an individual professor’s positionality, as Professor Meera E. Deo documents in her book Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia.

How can law schools as institutions respond to the special needs of law students who are caretakers and are at risk of heightened stress and burnout? As part of the ABA mandate that law schools provide substantial opportunities to explore “well-being practices,” law schools should offer meaningful courses and co-curricular activities to address law students’ well-being, including trainings, screenings, and policies to encourage work-life balance. These co-curricular programs should also have resources to address the particular needs of law students who are parents or caretakers. Some institutions do this already. For example, some schools have created a clearinghouse of information directing students to school and city-specific parenting resources, as well as child care subsidies and student groups.

Schools should also conduct internal assessments to learn about the experiences and needs of law students who are caregivers to consider whether policies and practices around leaves and broader resources for this community are responsive to needs. Creative responses including creating parenting support groups are warranted. Schools can also take steps to accommodate the schedules for working parents. For example, one law school designated one of the nine first year small section modules as the parent module (affectionately called the “mommy mod”) and classes were scheduled to align with times when school was open and to accommodate drop off and pick up responsibilities. Similarly, another school designed a part-time law program so law students with school age children take coursework while their children are in school. Finally, as a broader measure and perhaps an impetus for the cultural shift the moment demands, U.S. law schools should consider signing on to the International Guidelines for Wellbeing in Legal Education, which would require a comprehensive overhaul of law school structure, curriculum, and atmosphere with well-being in mind.

Assessment of ABA Standard 303(c)

The American Bar Association (ABA) Standard 303(c) mandates that law schools provide students with substantial education on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism to ensure they are equipped to serve a diverse client base and uphold justice in an inclusive legal environment. This requirement, effective for all law schools accredited by the ABA, emphasizes integrating this training at critical junctures in a law student's education, such as during orientation and within a course prior to graduation. Standard 303(c) encourages schools to create meaningful, context-specific programs that prepare future lawyers to understand and navigate the societal and cultural complexities affecting the legal system.

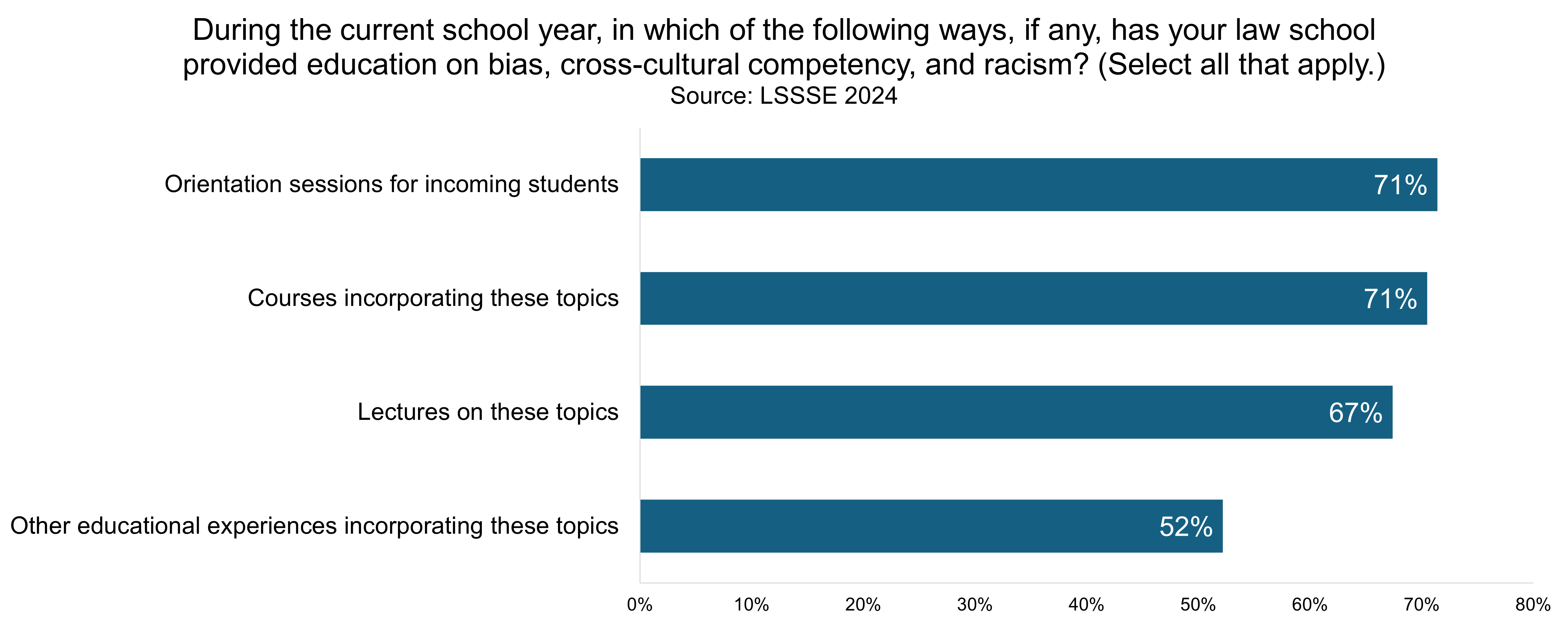

To aid law schools in evaluating their success toward meeting the requirements of Standard 303(c), LSSSE began asking questions about bias and anti-racism education during the 2024 survey administration. The question asks “During the current school year, in which of the following ways, if any, has your law school provided education on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism? (Select all that apply.)” and gives the following options:

- Orientation sessions for incoming students

- Lectures on these topics

- Courses incorporating these topics

- Other educational experiences incorporating these topics

Substantial numbers of law students are receiving bias, cross-cultural competency, and anti-racism training in each of the four venues. Orientations for incoming students and courses incorporating these topics were the most selected answers, encompassing 71% of students. Two-thirds (67%) of students had received lectures on these topics, and a little over half (52%) of students participated in other educational experiences incorporating these topics.

ABA Standard 303(c) represents a step toward fostering a more inclusive and culturally aware legal profession prepared to serve diverse communities with empathy, insight, and a commitment to equity. By mandating that law schools provide substantial education on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism, this Standard ensures that future lawyers are equipped not only to recognize but also to challenge the social and cultural biases that can impact the justice system. LSSSE data show that the majority of law students are receiving this essential training through orientations, lectures, and integrated courses. To assess whether students at your law school are having these experiences and to compare your law students to the national averages, sign up for LSSSE 2025. Registration is now open.

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Law Student Online Engagement and Universal Socratic

Christopher J. Robinette[1]

Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

In the fall of 2023, Southwestern Law School received ABA approval to operate the country’s first fully online Juris Doctor program. Moreover, to increase student flexibility, the program is asynchronous, with only a few voluntary synchronous sessions. In essence, the students and professor will not be online together in a Zoom room, but students will access videos of the professor and exercises on their own schedules.

As a law professor who has taught in-person courses for over twenty years, I deliberated a long time before volunteering to teach online. I love the energy of the face-to-face classroom and, frankly, I was somewhat skeptical about the efficacy of online law classes, particularly in the first year. In fact, one of the most compelling reasons that I agreed to teach online was the hope of improving my pedagogy in the “real” classroom. As I began planning my online course, however, I became excited about the possibilities particular to the online mode.

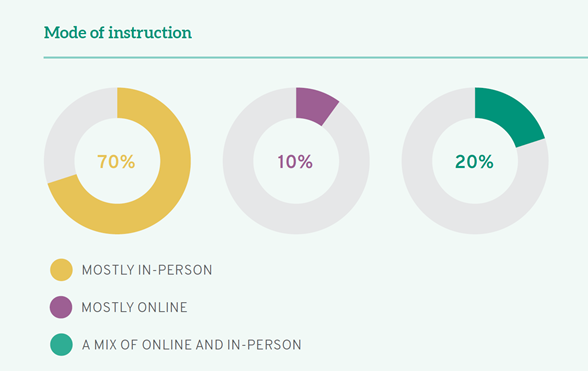

The 2022 LSSSE Annual Report, Success with Online Education, says half (50%) of all law students were enrolled in at least one course that was taught mostly or entirely online and every law school participating in the LSSSE survey offered at least some online courses. Most law students (70%) took courses that met in-person, though 10% took mostly online courses, and 20% reported that they had enrolled in a mix of courses that met online and in-person. Of those who did meet online, most (78%) were in synchronous classes; but 3% of LSSSE respondents in online courses met asynchronously and an additional 19% were in hybrid courses. Clearly, online education is here to stay and could grow even more prominent in the years ahead.

As an instructor, my biggest concern about teaching online was something about which LSSSE is expert: engagement. Keeping students engaged can be difficult under any circumstances, but it is especially challenging online. I believe a solution to the online engagement problem is not singular; instead, it lies in numerous program and instructional design decisions. With that in mind, I considered how law professors engage their students, particularly first years, in the traditional classroom. Of course, a major technique is the Socratic method, in which the professor asks a (usually cold-called) student increasingly challenging questions about a case. This is an interactive mode of teaching and learning that involves the students and does not conceive of them as passive recipients of knowledge. Although they exist, I do not need the overwhelming data telling me that active learning is superior. I can sense it in the fact that the air starts to go out of the room whenever I lecture my students for lengthy periods of time.

Was there a way to adapt the Socratic method to the online asynchronous environment? In thinking about this, I had to admit that one facet of the Socratic method in the classroom was not replicable. In the traditional classroom, the professor is able to tailor her follow-up questions precisely to the student’s answers. This is not possible in an asynchronous online class. But—and this is where I grasped that the online environment has advantages—you can ask all of the students all of the questions. In the traditional classroom, one student is on call. Ideally, we expect the other students to be following along and answering the questions silently for themselves. In reality, we know that at least some of them do not. They are spaced out, or shopping online, or simply exhausted. In an online course, all students can be engaged. And it can be verified.

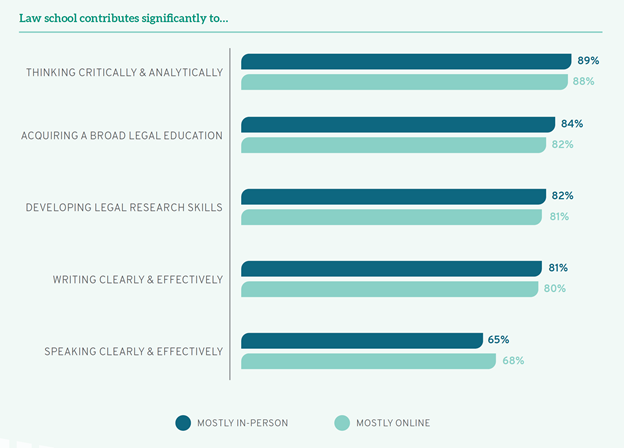

This is how I developed the Universal Socratic for my online course. For each module in my course, I selected one case that I found significant and created an interactive exercise around that case. I wrote five questions about the case. For the first few modules, I followed the structure of a basic case brief (facts, issue, holding, disposition, rationale), allowing the students to reinforce their briefing skills. As the modules progressed, I formulated more questions in the upper ranges of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analyzing, evaluating, and creating). Thanks to exercises like this, LSSSE data indicate that students believe legal education contributes to multiple skills, especially thinking critically and analytically, as much online as in-person.

I then drafted answers to the questions. Using Canvas’s Quizzes feature, I inserted the questions and required the students to answer them one at a time. After the student has answered each question, and before they answer the next question, they are shown my answer and are able to compare it to theirs. Not only asking the questions but providing prompt feedback is helpful to engage students. Using this process, the student and I are essentially having a dialogue, even though I do not have the benefit of their exact answer in real time in person. Moreover, every student in the class engages in the exercise of answering the questions.

Given the growth in online education, students will benefit from legal educators modifying effective face-to-face techniques, like the Socratic method, for the asynchronous online mode. When educators do so, they will find that some features of online education make it better than the original.

[1] I benefited greatly on this project from the ideas of my terrific colleagues Catherine Carpenter, John De Sousa, and Danni Hart.

Barriers to Choosing Public Interest Law Careers

Lawyers who practice public interest law are often driven by a desire to create positive social change and to advocate for marginalized or underserved communities. The work can be deeply rewarding as it allows lawyers to address issues like civil rights, environmental justice, housing, and access to healthcare. The sense of purpose and fulfillment from working on causes that align with personal values can be a significant motivator. However, there are potential barriers to pursing public interest work. To better understand these barriers, LSSSE partnered with Equal Justice Works in 2023 to survey students about how their law school supports public interest law, how their law school educates students on topics relevant to public interest law, and what barriers exist to pursuing a public interest law career. The joint final report that details the findings can be found here. In this blog post, we share some findings on the barriers to accepting a position in public interest law after graduation.

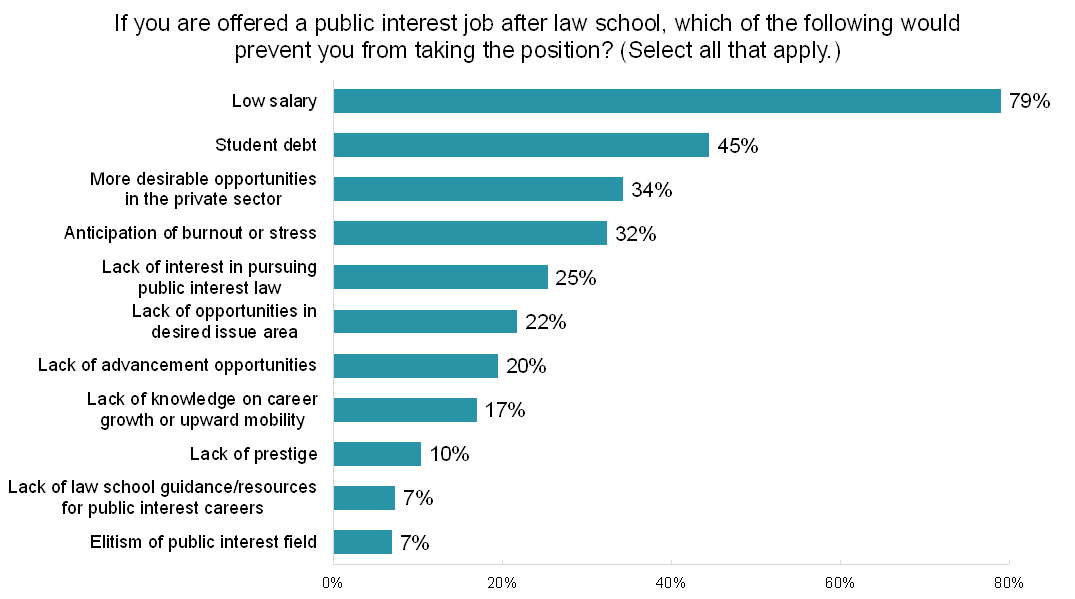

Law students were presented with a list of potential factors that would prevent them from taking a public interest law job after law school if they were offered one and instructed to select all the reasons that apply to them. Understandably, financial concerns were high on the list of reasons why students would choose not to accept a public interest law position. Nearly four out of five students (79%) cited low salary, and nearly half of students (45%) were concerned about their ability to pay off student debt. Interestingly, only about a third of students (34%) indicated they were motivated by more desirable opportunities in the private sector, and only a quarter (25%) cited a lack of interest in public interest law. This suggests students are attracted to public interest law, but their interest is tempered by financial considerations. One bright spot is that students do appear to be well-supported in law school guidance and resources for public interest careers. Only 7% of students cited a lack of this type of support as a barrier to pursuing a public interest career.

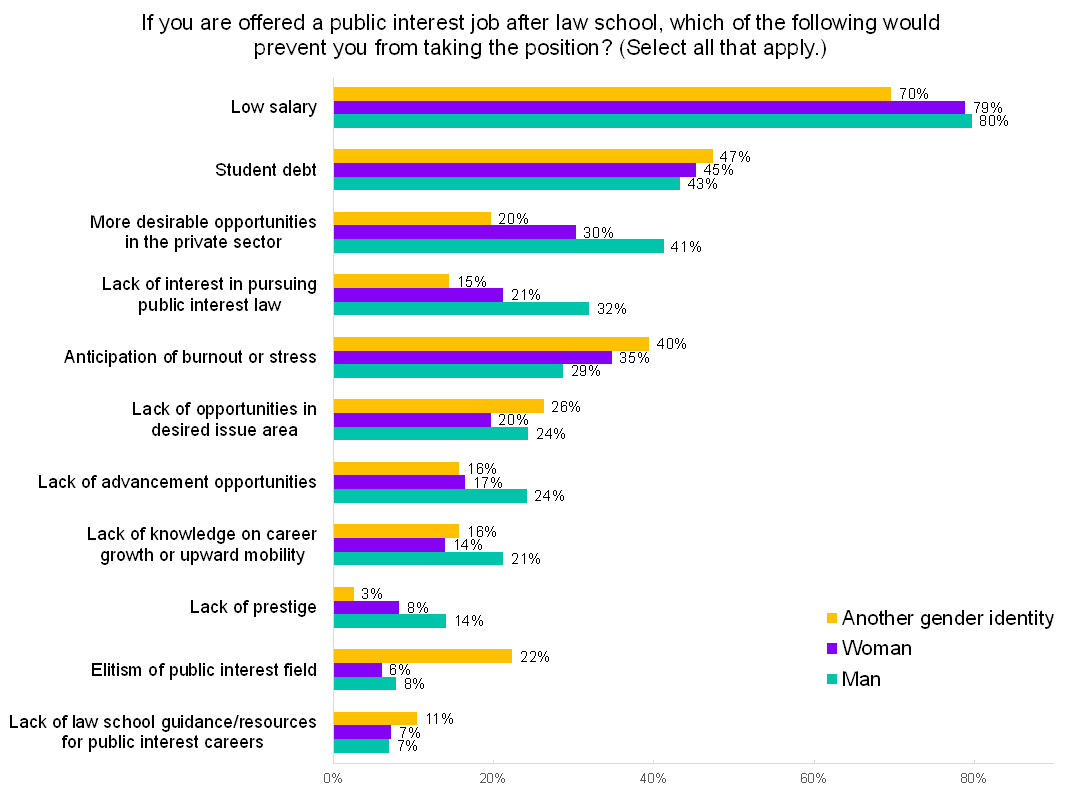

There are some notable gender differences in factors preventing students from taking a public interest law position. Men are more likely to see the private sector as more desirable and to have a lack of interest in public interest law. They are also more concerned than women and people of other gender identities about a lack of prestige and a lack of advancement opportunities or upward mobility in the public interest law sphere. People who do not identify as a man or a woman are less deterred by the prospect of a low salary, and they are less likely to see the private sector as more desirable or to cite a lack of interest in public interest law. However, they are the group most likely to be concerned about potential burnout or stress and to be concerned about elitism in the public interest field. Women tend to fall somewhere in between men and people of other gender identities in terms of which factors are most likely to deter them from taking a public interest job after law school. They are equally concerned about low salary as men, but they are less likely to cite a lack of interest or more desirable opportunities in the private sector as reasons not to pursue public interest. However, women are the least likely of all genders to cite a lack of opportunities in their desired issue area as a reason to avoid public interest.

Some barriers to working in public interest law—such as financial considerations—are concerns of a large majority of students. However, some concerns are more salient to certain subgroups of students. Employers interested in recruiting and retaining new public interest lawyers may consider tailoring their efforts to address these issues in order to increase their ability to attract potential future employees.

The Role of Data in Mission-Focused Law School Leadership

The Role of Data in Mission-Focused Law School Leadership

Jelani Jefferson Exum

Dean & Rose DiMartino and Karen Sue Smith Professor of Law

St. John’s University School of Law

I am a mission-focused leader. Of course, many law school deans would describe themselves in the same manner. Every law school has a mission that identifies and guides the institution. Most law deans were drawn to law school leadership because we believe in the transformative power of legal education, but also because we believe in the mission of our institution. That is my story. As the new Dean of St. John’s University School of Law, I am inspired and guided by the mission of the law school. The mission of St. John’s Law focuses on providing access to an excellent legal education for a diverse student body; teaching and scholarly innovation; building an antiracist community; inspiring civic engagement; and developing leaders. I realize that in order to lead the law school in a manner that stays true to this mission, I need to have an in-depth and nuanced understanding of our student body and their experiences. The data provided by LSSSE are a powerful tool for any law dean – especially one new to an institution – to learn about their student population and the broader legal education landscape. That data, in turn, can assist a dean in supporting the mission of the school.

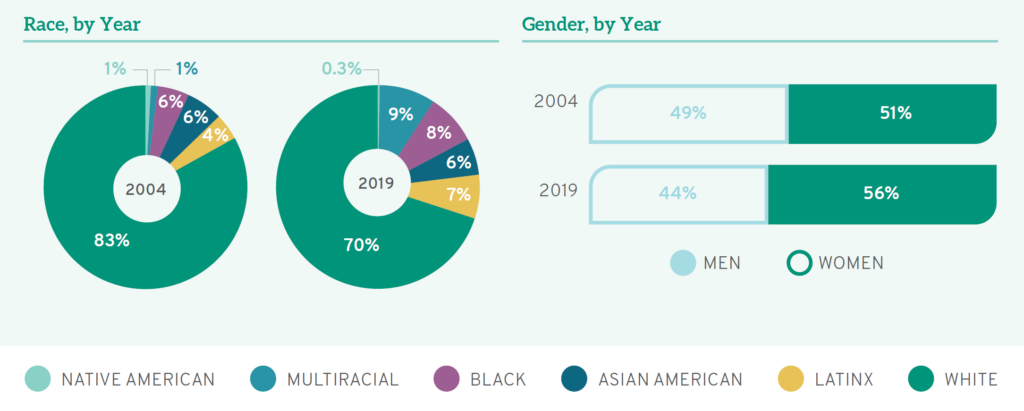

There may have been a time in legal education when staying true to mission was an easy task. That certainly is not the case in today’s educational and legal climate. For instance, for nearly 100 years, St. John’s Law has opened its doors to a diverse student body – many of whom were first generation college or law school students – and provided them with access to a legal education that would transform their economic mobility. This focus on making legal education more accessible to a diverse group of students, which has been a hallmark of St. John’s Law, is increasingly challenging. The recent constraints placed on admissions by the Supreme Court means that fulfilling this diversity mission priority requires more intentional work on the part of law school deans and their admissions teams. LSSEE’s longitudinal data, such as that provided in The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, provides important information on the shifts in the demographics and needs of law students over the years.

The data summaries are very detailed and break out certain results based on students’ race, gender, sexual orientation, and age. These statistics can aid in understanding the evolving expectations of students in ways that can also inform methods of communicating your school’s value and strengths to a diverse body of prospective students.

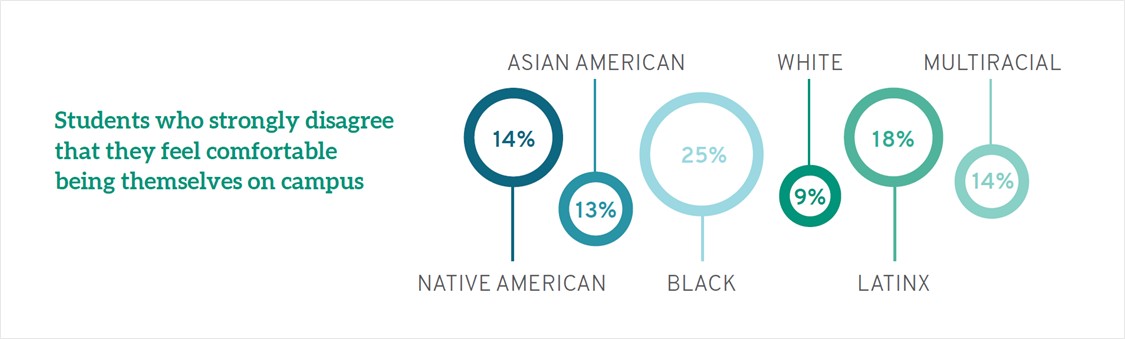

Understanding a diverse student body is not only important in maintaining a mission of access, it is also vital to schools that are working to stay true to an antiracism mission. LSSSE data has been extremely useful in illuminating the culture of law schools. Specifically, the 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, provides in-depth information on a variety of topics that give insight into the student experience, from institutional support, to belonging, to diversity skills.

Before I became dean, St. John’s Law used this report, in addition to other school-specific data, to inform the development of its annual Anti-Racism Day programming for 1L students. Now that I have joined as dean, this type of LSSSE data has helped me to think through, not only admissions challenges, but various aspects of our school where the effects of institutional racism can be investigated and addressed – from assessments to student services to teaching strategies. This information also helps us to measure the success of our commitment to an innovative application of knowledge. We will continue to use LSSSE reports as an indirect measures of student success and competence in our learning outcomes. LSSSE survey results give us a mechanism to learn what students think about their learning and experience in law school to use in concert with our more direct assessment measures. In this way, LSSSE data are valuable across mission goals, tying together the points relevant to antiracism, student learning, and overall student success and well-being.

Today’s law school has more need than ever to draw upon its mission statement to chart a path forward. There are many pressures and changes in legal education that make it easy for a school to lose its way. From addressing issues of free speech and academic freedom in light of concerns regarding student inclusion and belonging to navigating how to embrace and champion diversity and access within new legal limits --a law school can easily veer off target and lose its foundational values. LSSSE and the data it so thoughtfully collects and disseminates can be a powerful tool in staying the course for a mission-focused leader.

Joint Degree and Certificate Programs

Law students may choose to pursue a joint degree or a certificate to enhance their academic and professional credentials by acquiring specialized knowledge and skills that complement the standard legal education. A joint degree program allows a student to earn two degrees in less time and with fewer credits than if they pursued each degree separately. Joint degree programs, such as those combining a Juris Doctor (JD) with a Master of Business Administration (MBA) or a Master of Public Administration (MPA), offer a comprehensive understanding of related fields, which broadens career opportunities and provides a competitive edge. Similarly, certificate programs in areas such as intellectual property law, environmental law, or international human rights allow students to gain targeted expertise that can be applicable in their future legal practice.

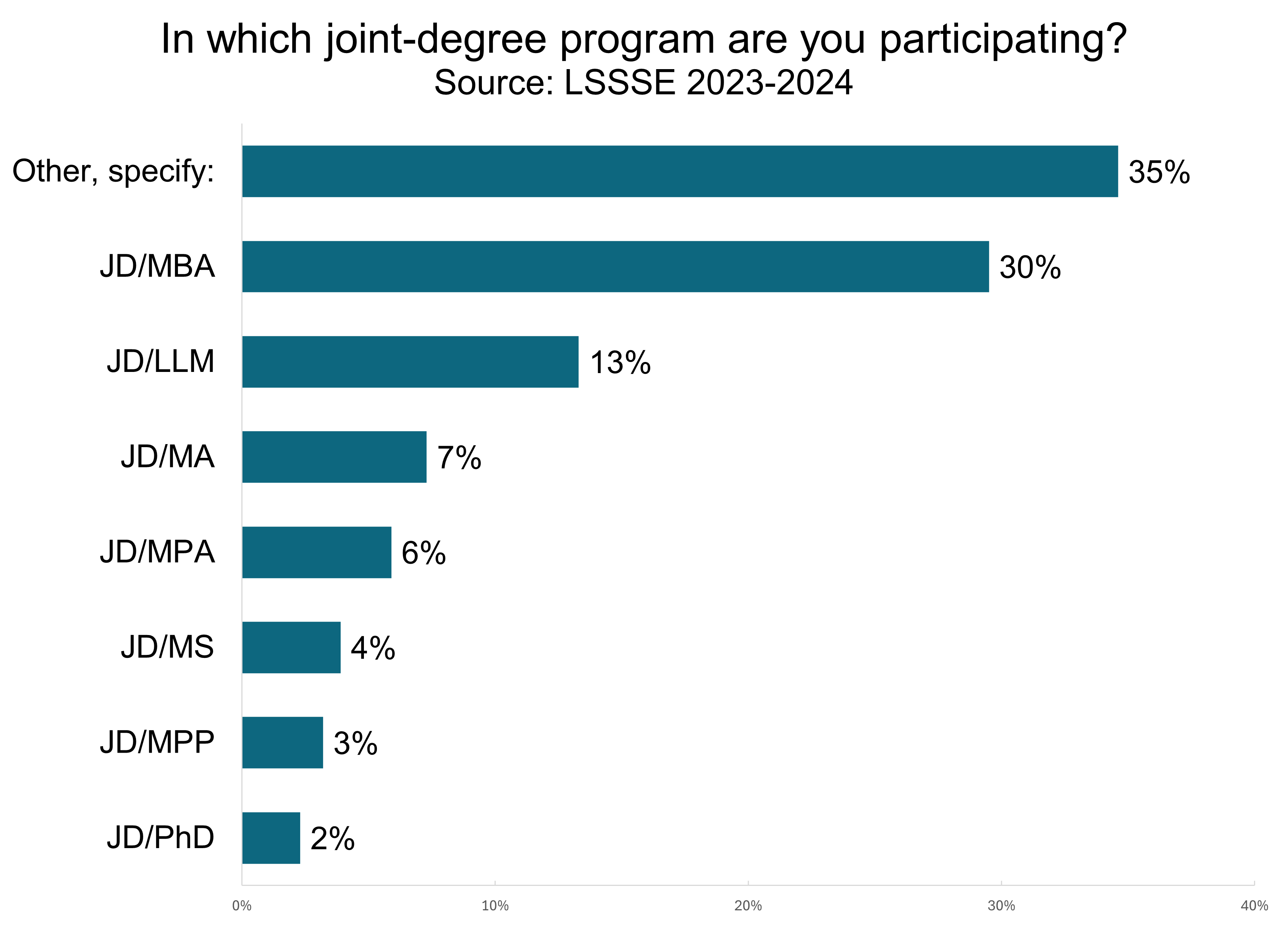

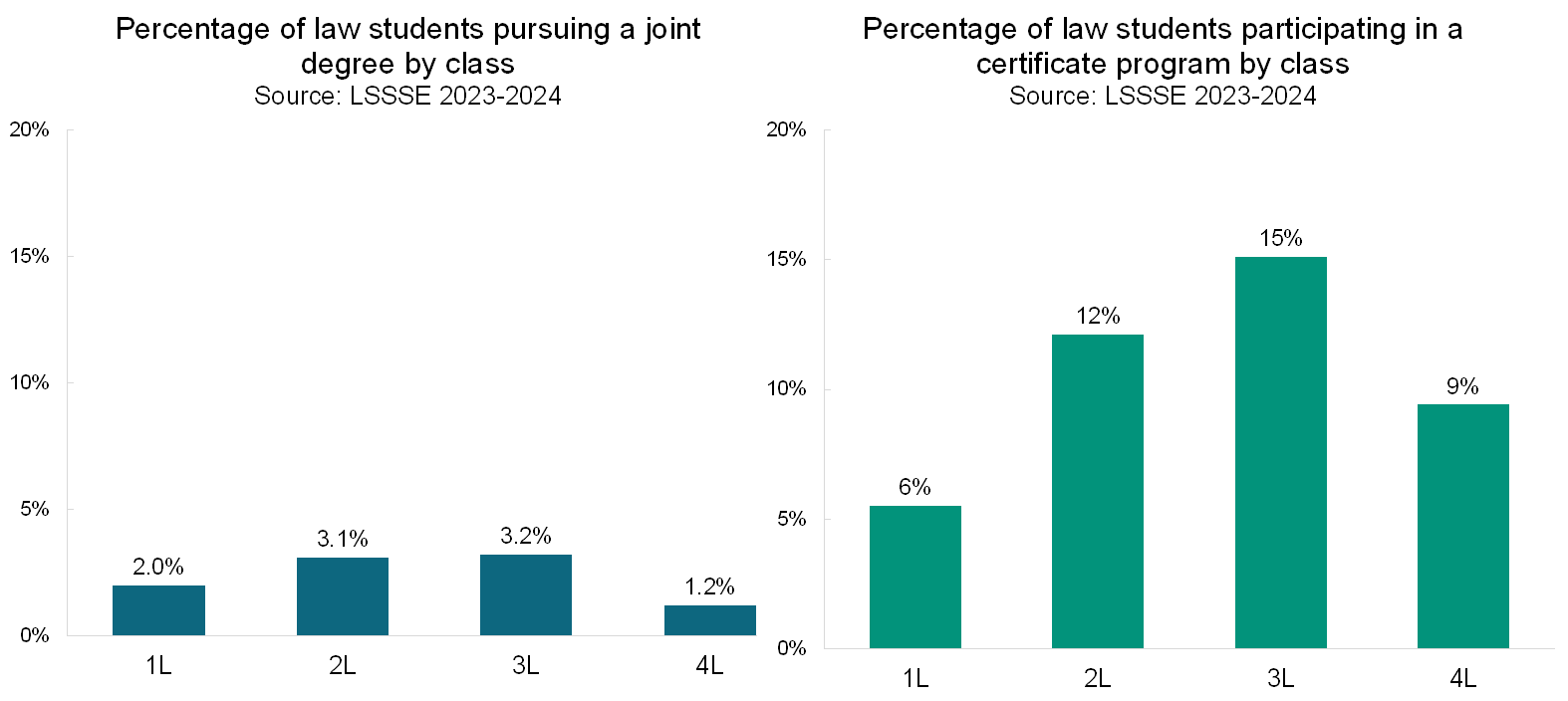

Just under three percent of LSSSE respondents were completing a joint degree in 2023 and 2024. Joint degree programs are often quite specific to the unique offerings of a particular law school. In fact, the most popular joint degree program on the survey is “Other, specify.” Of the LSSSE-provided options, the combined JD/MBA is by far the most popular choice among joint degree students (30%), followed by the JD/LLM (13%), the JD/MA (7%), and the JD/MPA (6%). Only 2% of joint degree students are pursuing a JD/PhD.

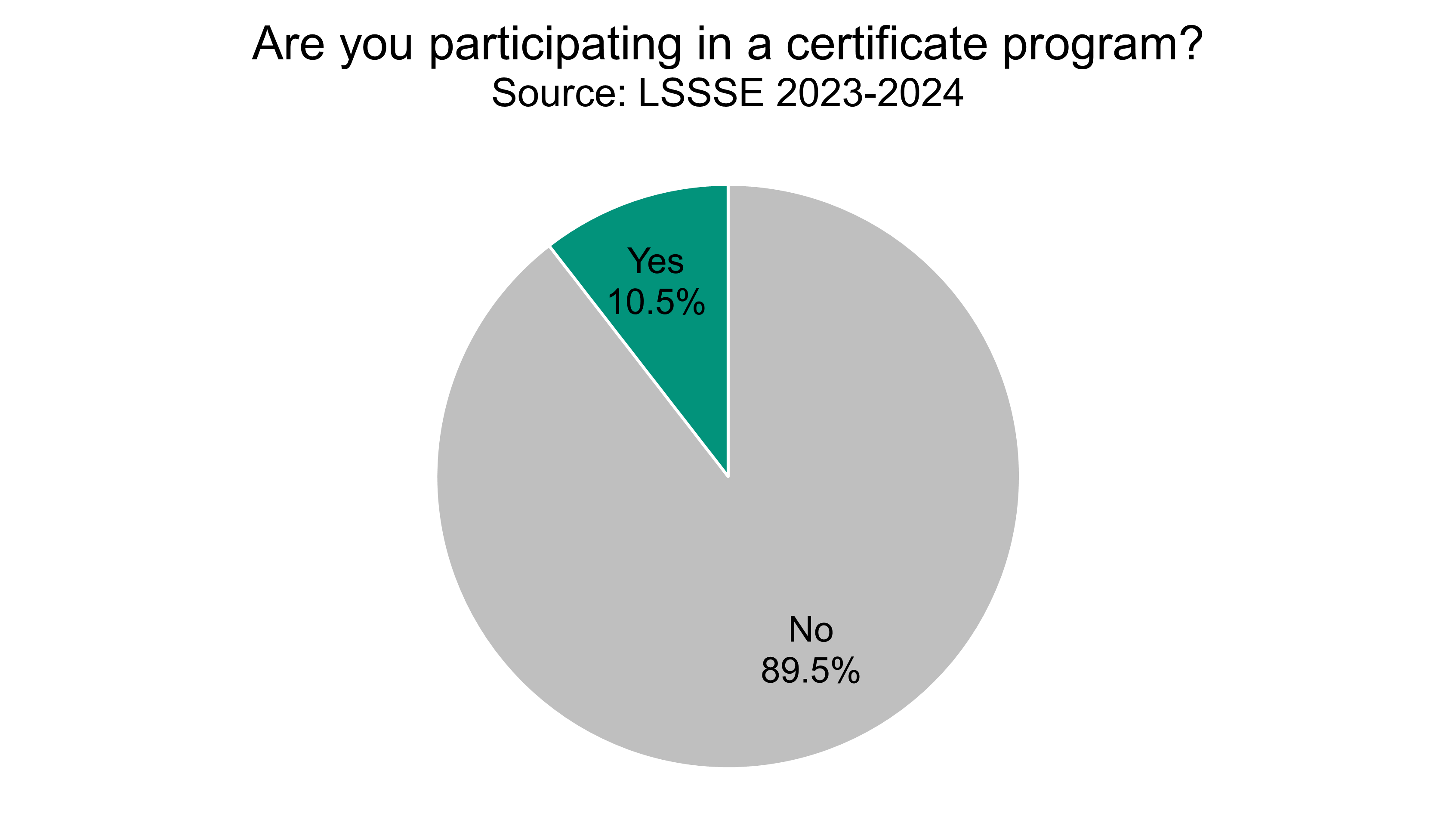

Certificate programs can provide additional content knowledge without the commitment of another entire degree, which makes them a somewhat more popular option. Nearly 11% of LSSSE respondents were pursuing a certificate in 2023 and 2024. The most common certificate program specializations included Health Law, Intellectual Property Law, Business Law, and Environmental Law.

Law students appear to add on certificates as they progress through law school. Only 6% of 1Ls were pursuing a certificate, but among 3Ls, that number rose to 15%. It may be that 1L students do not realize the value, availability, or relative ease of completion of certificates during the course of completing their law degrees and only add them on once that has been made clear to them. This may signal that law schools could advertise their certificate offerings more clearly to prospective and incoming students. Interestingly, there is also a small difference in the percentage of students who are pursuing joint degrees across their years in law school. Around 2% of 1L students were completing a joint degree, compared to 3.2% of 3L students.

By completing joint degree programs and earning certificates, law students can demonstrate their commitment to interdisciplinary learning and their ability to integrate legal principles with other subject areas. These students ultimately enhance their versatility and effectiveness as practitioners in a complex legal landscape.

By completing joint degree programs and earning certificates, law students can demonstrate their commitment to interdisciplinary learning and their ability to integrate legal principles with other subject areas. These students ultimately enhance their versatility and effectiveness as practitioners in a complex legal landscape.

Improve the Diversity of the Profession By Addressing the Costs of Becoming a Lawyer

Improve the Diversity of the Profession By Addressing the Costs of Becoming a Lawyer

Joan Howarth

Professor Emerita, Boyd School of Law, UNLV

Dean Emerita, Michigan State University College of Law

One of the themes of my book, Shaping the Bar: The Future of Attorney Licensing (Stanford University Press 2023), is that becoming a lawyer in the United States is too expensive. Unlike in many other countries, the U.S. law degree typically requires three or four years of expensive postgraduate study, which should be enough time to produce and assess minimum competence to practice law. But after graduating from law school bar candidates typically spend two more months and thousands of dollars immersed in bar prep with a commercial company. The billion-dollar bar prep industry covers the gap between what was learned in law school and what is required to pass a bar exam. Student loans do not cover the cost of those bar prep courses or the living expenses while preparing for the exam. Law graduates without financial resources face financial emergencies – or time-consuming jobs for paychecks -- when they are supposed to be using all their time preparing for the bar exam.

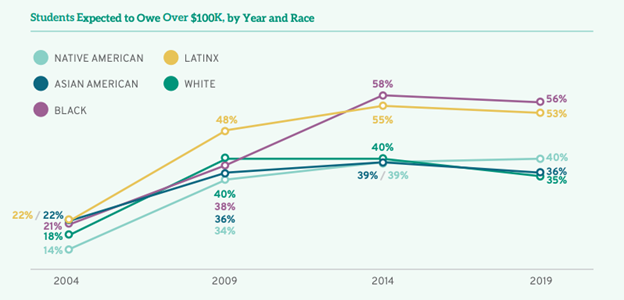

Not surprisingly, then, research shows that economic assets are a significant factor in bar passage. And LSSSE research shows us the connections between the excessive expense of becoming a lawyer and the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in bar passage rate.

The racial and ethnic bar passage disparities are extreme. For example, the national ABA statistics for first time passers in 2023-24 show White candidates passing at 83%, compared to Black candidates (57%) with Asians and Hispanics in the middle (75% and 69%, respectively).

These disturbing figures are very related to the expense of becoming a lawyer.

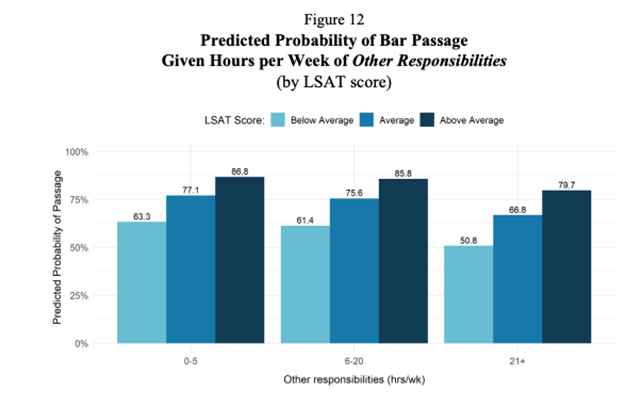

The 2021 National Report of Findings for the AccessLex/LSSSE Bar Exam Success Initiative showed that law grads who take care of children or work in non-law jobs have a harder time passing bar exams.

These problems were confirmed in a large 2021 study of New York bar takers. Even after controlling for LSAT and other academic factors, law grads who had greater financial resources were significantly more likely to pass but grads who worked for pay were significantly less likely to pass.

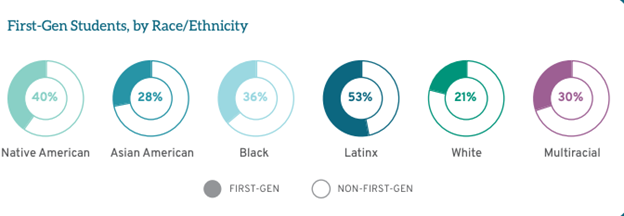

Who are the law grads with fewer financial resources? LSSSE research shows us that Black and Latinx students are carrying more law school debt than White students.

LSSSE’s 2023 Annual Report focused on first-gen law students shows that law students who are the first in their families to graduate from college are more likely to be from underrepresented communities.

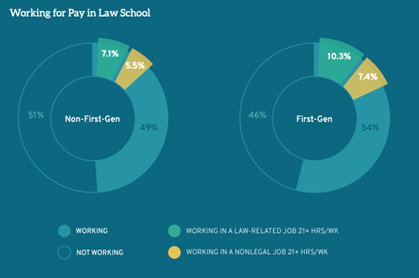

First-gen students are also more likely to work for money and work in non-law related jobs in law school.

LSSSE data from that report show that first-gen law students are also more likely to care for dependents.

In other words, law graduates who could be great lawyers—too many of whom are people of color, first-generation law students, and parents—are failing bar exams because they cannot drop everything else for two months to devote themselves to memorizing thousands of rules, most of which they would not use in practicing law, and most of which they will forget quickly after walking out of the exam.

Finally, though, after decades of stability -- or stagnation -- in attorney licensing, change is here. And some of the changes, such as the new pathway to licensure in Oregon based on supervised practice instead of a traditional bar exam, or the Nevada Plan in which most of the requirements can be satisfied during law school, should significantly decrease the costs of licensure and add flexibility for candidates with responsibilities beyond studying for a bar exam. These reforms are long overdue.

Learning to Think Like a Lawyer

Learning to think like a lawyer is crucial for developing essential analytical skills and a nuanced understanding of legal principles. This process involves honing the ability to critically assess legal issues, construct persuasive arguments, and anticipate counterarguments. Learning to think like a lawyer is challenging because it requires a shift in mindset and the development of complex analytical skills. Law students must master intricate legal concepts and apply them to varied contexts, often under pressure. This involves not only understanding the law but also critically analyzing case precedents and identifying subtle distinctions. Additionally, the emphasis on precision in language and argumentation can be daunting, as even minor errors can significantly impact legal outcomes. By the time they are ready to graduate, most law students have learned to cultivate a mindset that prioritizes logical reasoning and ethical considerations, which are vital for effective advocacy. Ultimately, mastering this way of thinking not only prepares students for successful careers in law but also equips them to navigate complex societal issues with integrity and insight.

LSSSE provides a Learning to Think Like a Lawyer (LTTLL) Engagement Indicator that is a succinct metric for understanding the degree to which students are engaging in this learning process. The LTTLL Engagement Indicator combines several individual survey questions that are statistically and conceptually related to one another. This makes Engagement Indicators meaningful for comparisons because they reduce the risk of relying too heavily on any individual survey question. The LTTLL Engagement Indicator combines the following questions from the main LSSSE survey:

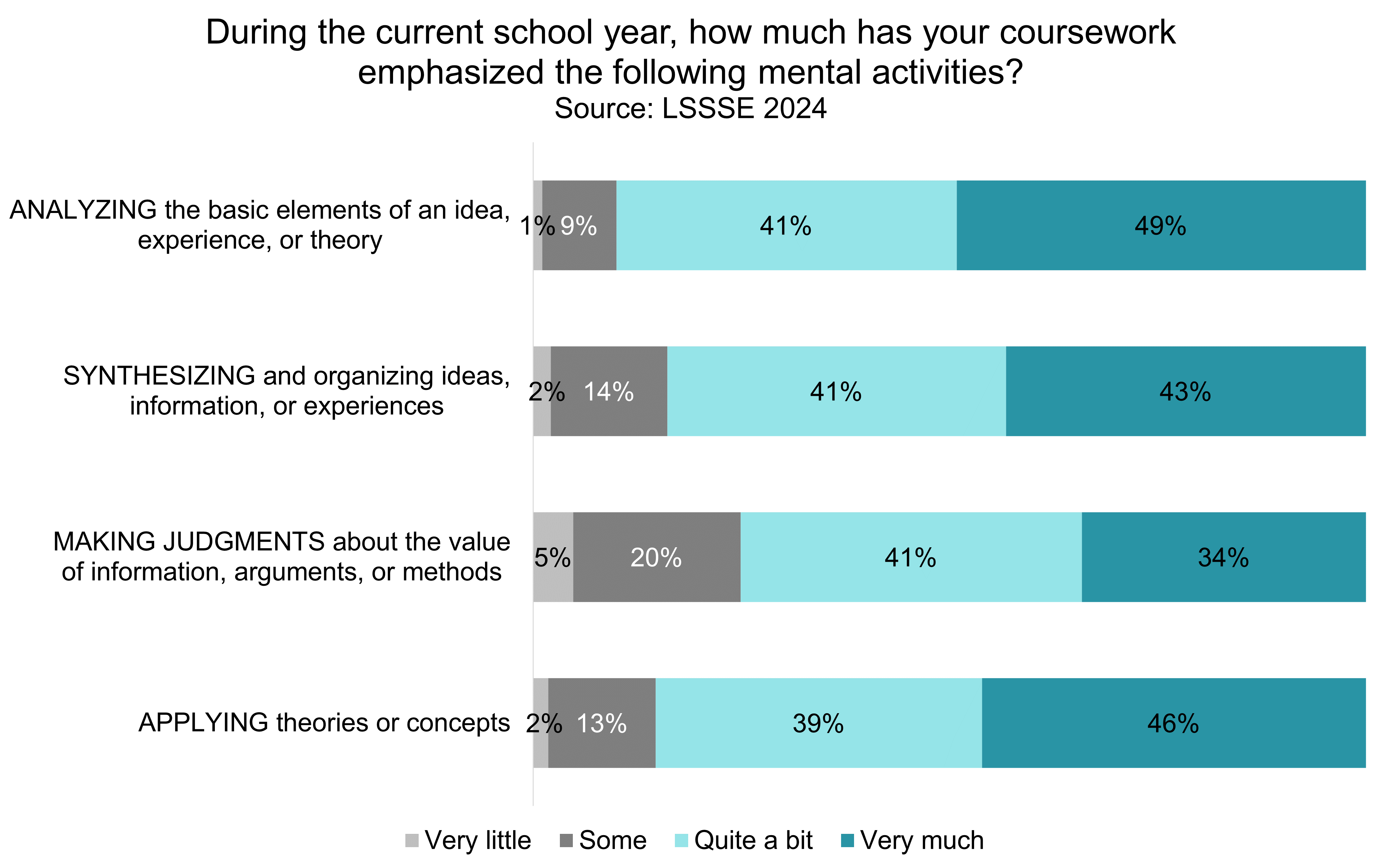

During the current school year, how much has your coursework emphasized the following mental activities?

- Analyzing the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory, such as examining a particular case or situation in depth, and considering its components

- Synthesizing and organizing ideas, information, or experiences into new, more complex interpretations and relationships

- Making judgments about the value of information, arguments, or methods, such as examining how others gathered and interpreted data and assessing the soundness of their conclusions

- Applying theories or concepts to practical problems or in new situations

The response options are “very much,” “quite a bit,” “some,” and “very little.”

Of the four cognitive activities, students are most heavily engaged in analyzing the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory. Ninety percent of law students do this often or very often. Next comes applying theories or concepts to practical problems or in new situations (85%) and synthesizing and organizing ideas, information, or experiences into new, more complex interpretations and relationships (84%). Three-quarters (75%) of law students frequently make judgments about the value of information, arguments, or methods, such as examining how others gathered and interpreted data and assessing the soundness of their conclusions.

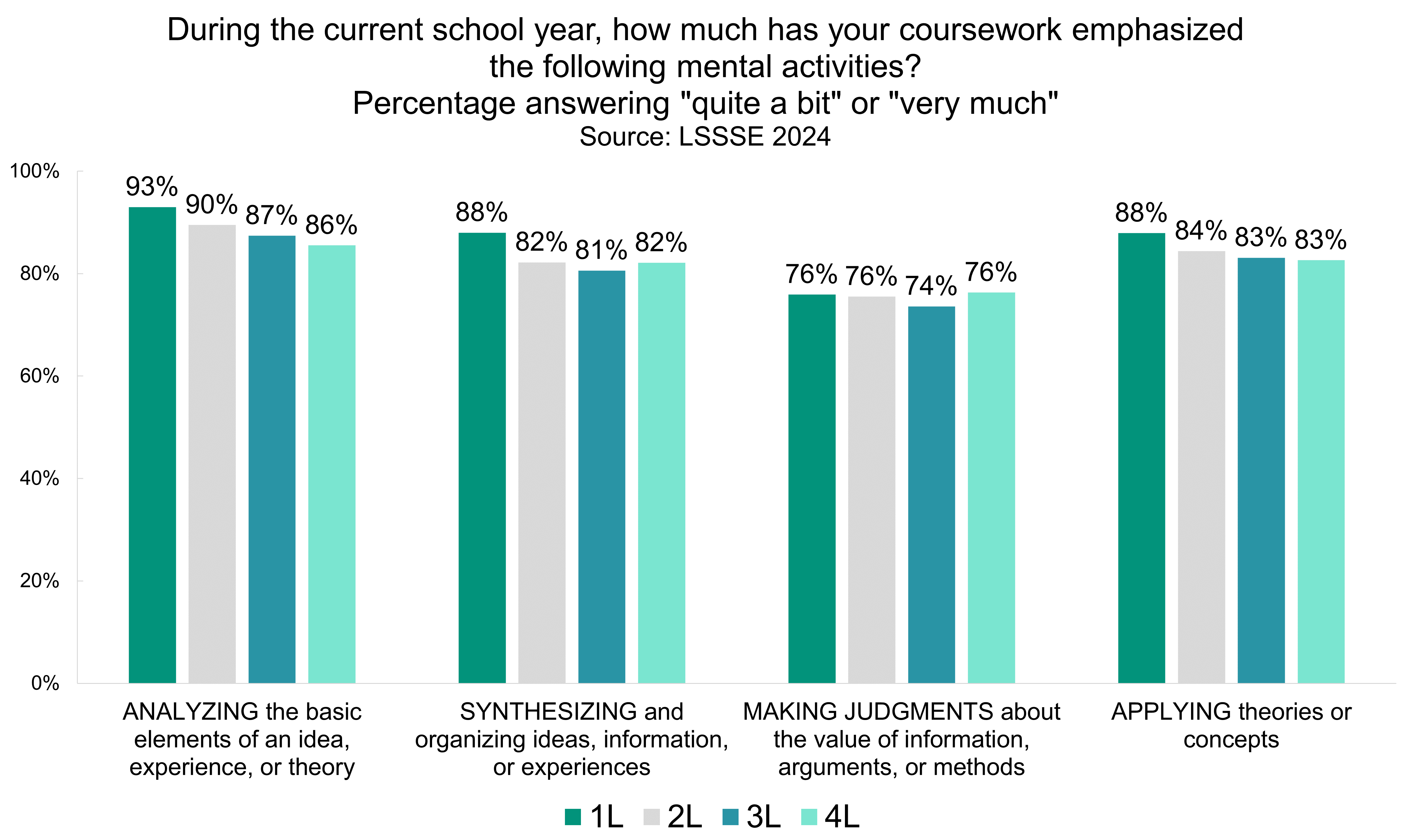

There are some interesting differences in how students respond to these questions across class years. 1L students are more likely to frequently engage in all the LTTLL mental activities compared to 2L and 3L students. For example, 93% of 1L students frequently analyze the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory, compared to only 86% of 3L students. Generally, 1L students are somewhat more engaged with the law school experience and more enthusiastic overall relative to their more seasoned peers, so that might explain this discrepancy. However, it is also possible that 3L students have become so fluent with these processes that they do not necessarily note them in isolation from the type of legal thinking which has become automatic to them.

By applying legal theories and concepts to real-world scenarios, aspiring lawyers learn to navigate the intricacies of the law, develop strategic approaches, and ultimately advocate effectively for their clients. This comprehensive skill set is essential for rigorous legal thinking and practice. LSSSE provides customized tools to gauge how well your students are learning these crucial mental processes as well as ways to compare your students to selected peers and national averages. Contact us to learn more.

Artificial Intelligence and JD Students

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the ability of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as reasoning, learning, or decision making. AI has been applied to various domains, including law, where it can assist in research, drafting, analysis, or prediction. However, the use of AI in the law is certainly not without controversy, particularly given the high-profile and embarrassing incidents in which lawyers who had not properly vetted their AI bot’s research included AI hallucinations in court filings.

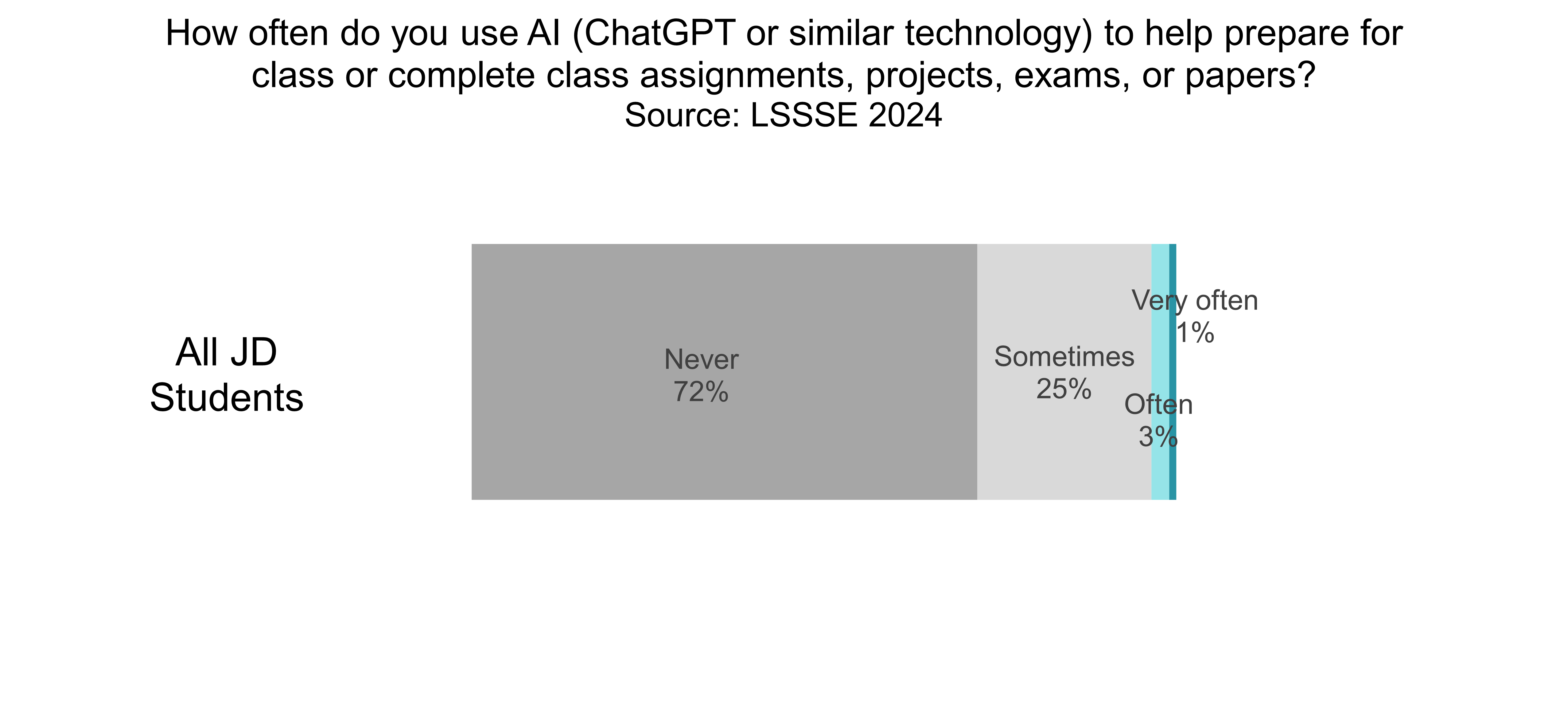

Institutions of higher education are currently grappling with the question of whether artificial intelligence is an essential tool of the future workforce or a means by which students may attempt to bypass their own educational enrichment and critical thinking skill development. We wanted to know how often JD students are currently using AI in their law school coursework. In 2024, LSSSE added the following question:

How often do you use AI (ChatGPT or similar technology) to help prepare for class or complete class assignments, projects, exams, or papers?

- Never

- Sometimes

- Often

- Very often

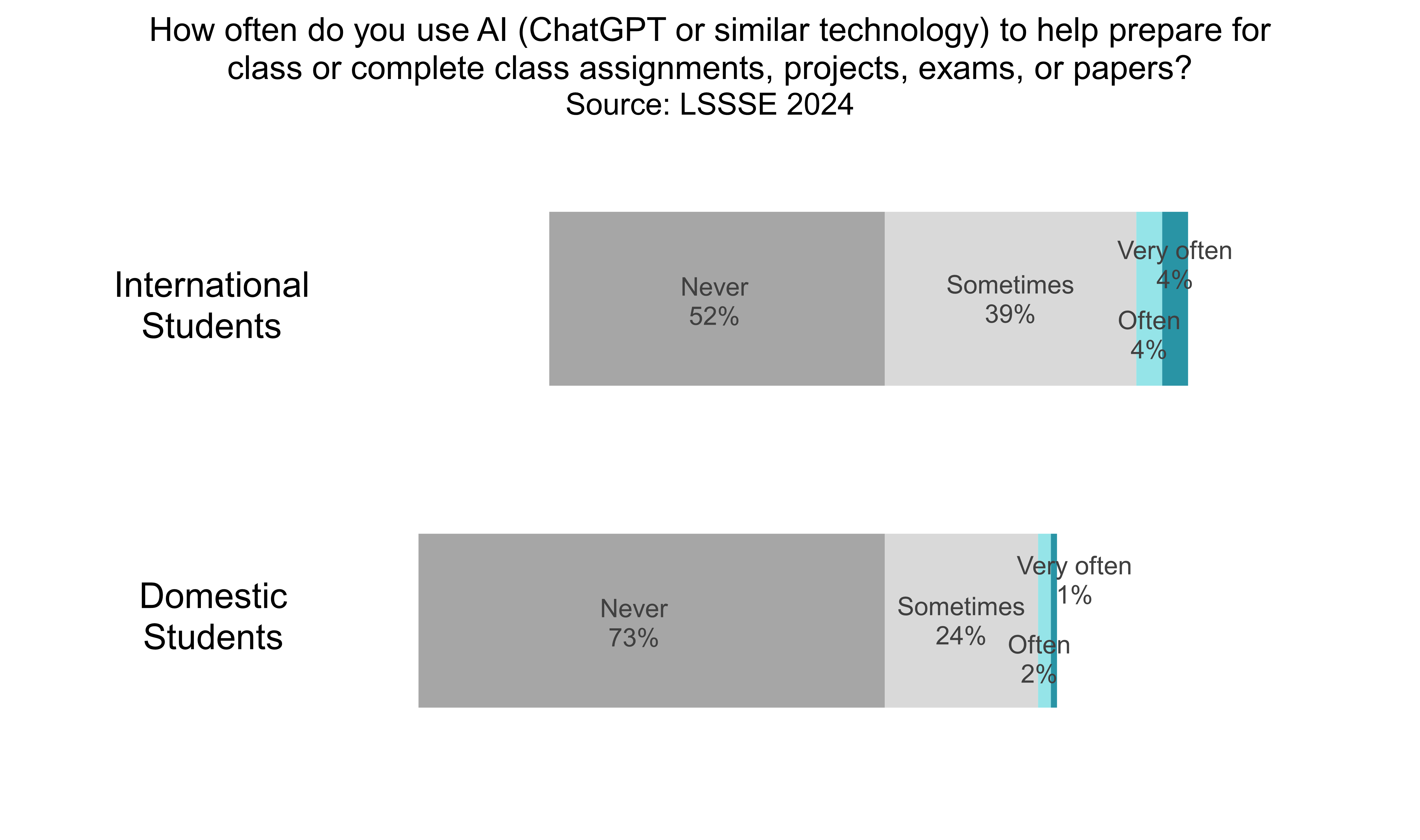

Our analysis shows that most law students are not currently using AI in their coursework at all. Almost three-quarters (72%) never use AI to prepare for class or complete assignments. A quarter of law students (25%) sometimes use AI in their coursework, and only 4% use it often or very often.

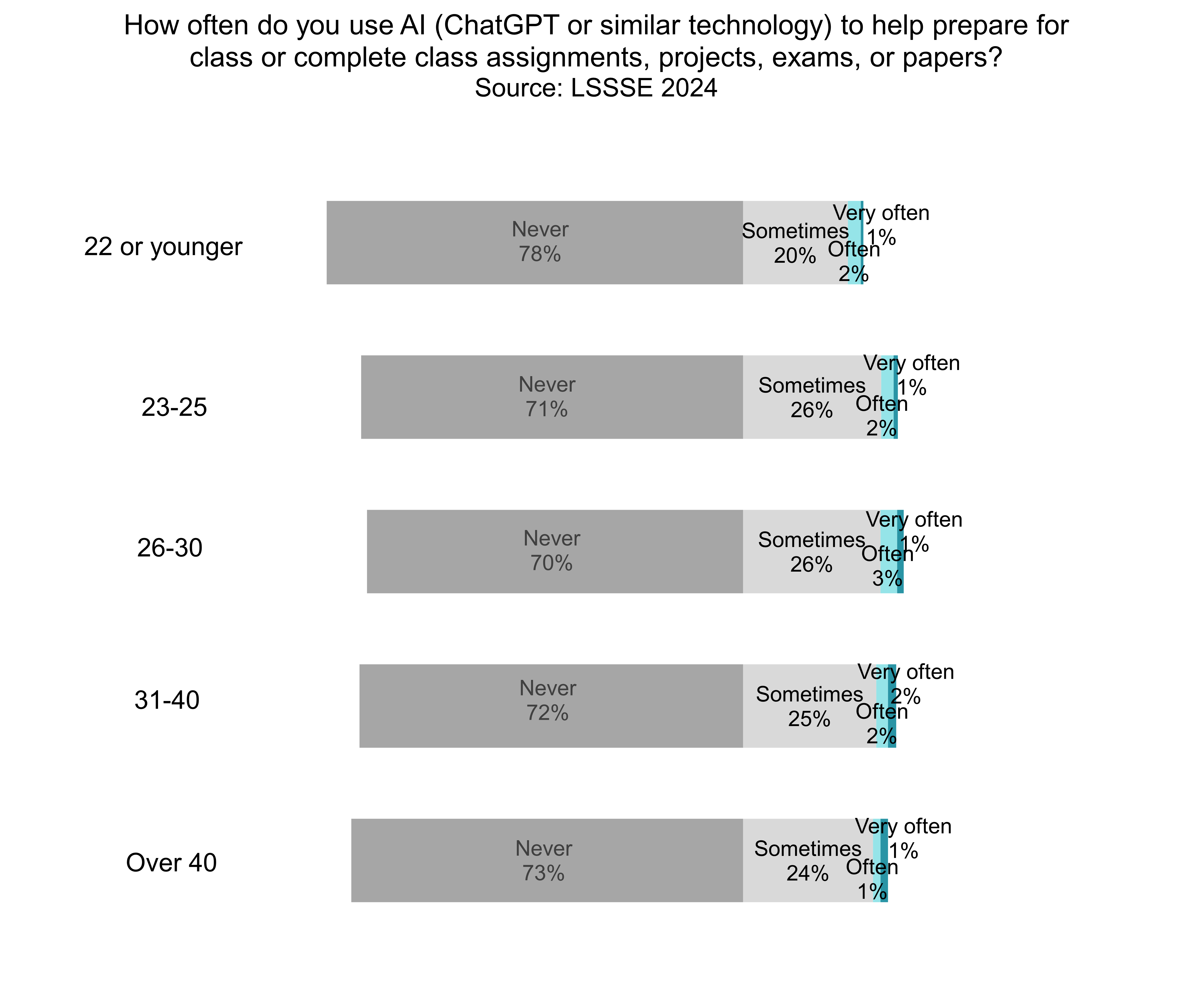

There are only slight generational differences in AI usage, with students in the 23-30 age group a perhaps a tiny bit more likely to use AI than other students. Interestingly, law students who are 22 or younger are the least likely age group to use AI for class preparation or assignments, with only 22% doing so at least sometimes.

However, international law students are much more likely than domestic law students to use AI for their law school coursework. Almost half of international law students (48%) use AI at least sometimes compared to only 27% of domestic law students. This parallels a larger trend in undergraduate education in which U.S. college students are much less likely to use AI than their counterparts elsewhere in the world. International students attending U.S. law schools who speak English as a second language may be drawn to AI because of the ways it can be harnessed to support the unique needs of multilingual students, particularly in decoding complex texts. Whether AI usage for this or any other purpose is necessarily desirable remains to be seen, although it is useful to note that students are already accessing and using these tools.

AI usage among law students in the U.S. is currently quite low, with most students never using it for their coursework. There are some variations by age and nationality, particularly with international law students using AI tools at a much higher rate than domestic law students. Law schools would be wise to pay attention to both the potential benefits of AI for legal research and writing, as well as the challenges and limitations of AI in the legal domain. LSSSE will continue to track AI usage to understand the degree to which law students are using these tools in their pursuit of learning and understanding the law.