Law Students are Highly Satisfied with Law Libraries

Law libraries are an essential cornerstone of legal education, providing students with the resources, spaces, and support needed to excel academically and to prepare for their future careers. Understanding how students feel about their law libraries is critical for ensuring these spaces and services effectively meet their needs. Exploring student satisfaction provides valuable insights into what is working well and where improvements can be made, helping law schools enhance the library experience and strengthen its role in fostering academic and professional success.

The Law Library topical module is an extension of the LSSSE survey that provides participating law schools with the opportunity to assess specific features of their law library including satisfaction with library training and support, quality of print and online resources, usefulness of physical spaces, and achievement of learning outcomes related to legal research. Today we will share satisfaction with some of the general features of academic law libraries using data from the 22 law schools that administered the Law Library module between 2022 and 2024.

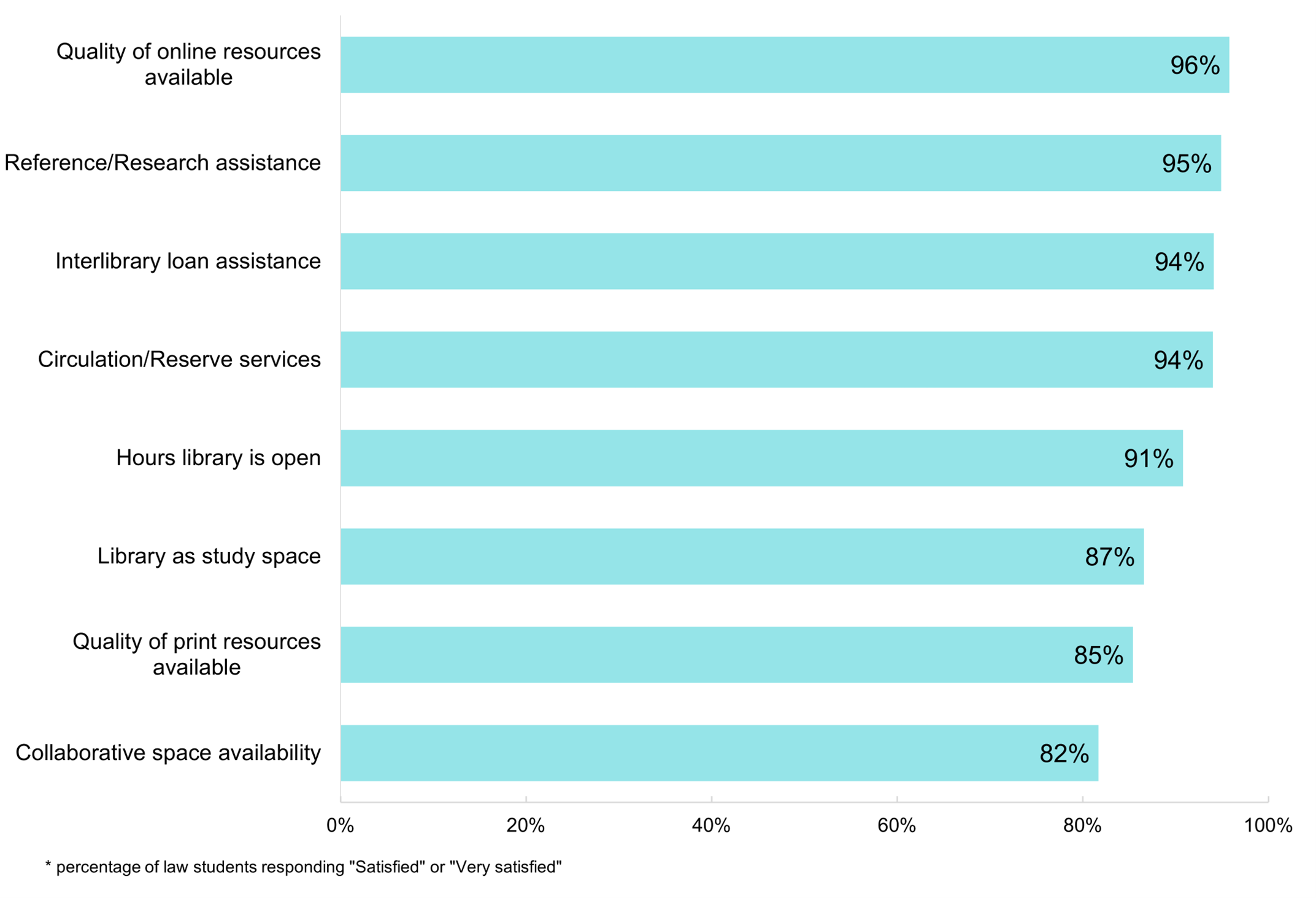

Four in five law students (82%) used the law library in the past year, and those students using the law library are are generally very satisfied with the services they receive. An astonishing 94+% of law library users are satisfied or highly satisfied with the quality of their law library’s online resources, reference/research assistance, interlibrary loan assistance, and circulation/reserve services. When students are dissatisfied with aspects of their library, their concerns are more likely to be related to access to the physical spaces, including hours the library is open (91% satisfaction), use of the library as a study space (87% satisfaction), and collaborative space availability (82% satisfaction). These satisfaction levels are still quite high, however, and this dissatisfaction can be viewed as a sign that students’ major complaints are that they want more of the library: longer hours and more collaborative and individual workspaces to use.

Law libraries play a vital role in shaping the academic and professional success of law students. The high levels of satisfaction with key library services underscore the critical support these libraries provide. The areas where students express less satisfaction highlight opportunities for growth, particularly in enhancing access to physical spaces. By listening to students' feedback and addressing their needs, law schools can ensure their libraries remain dynamic, indispensable resources that empower students to thrive.

Joint Degree and Certificate Programs

Law students may choose to pursue a joint degree or a certificate to enhance their academic and professional credentials by acquiring specialized knowledge and skills that complement the standard legal education. A joint degree program allows a student to earn two degrees in less time and with fewer credits than if they pursued each degree separately. Joint degree programs, such as those combining a Juris Doctor (JD) with a Master of Business Administration (MBA) or a Master of Public Administration (MPA), offer a comprehensive understanding of related fields, which broadens career opportunities and provides a competitive edge. Similarly, certificate programs in areas such as intellectual property law, environmental law, or international human rights allow students to gain targeted expertise that can be applicable in their future legal practice.

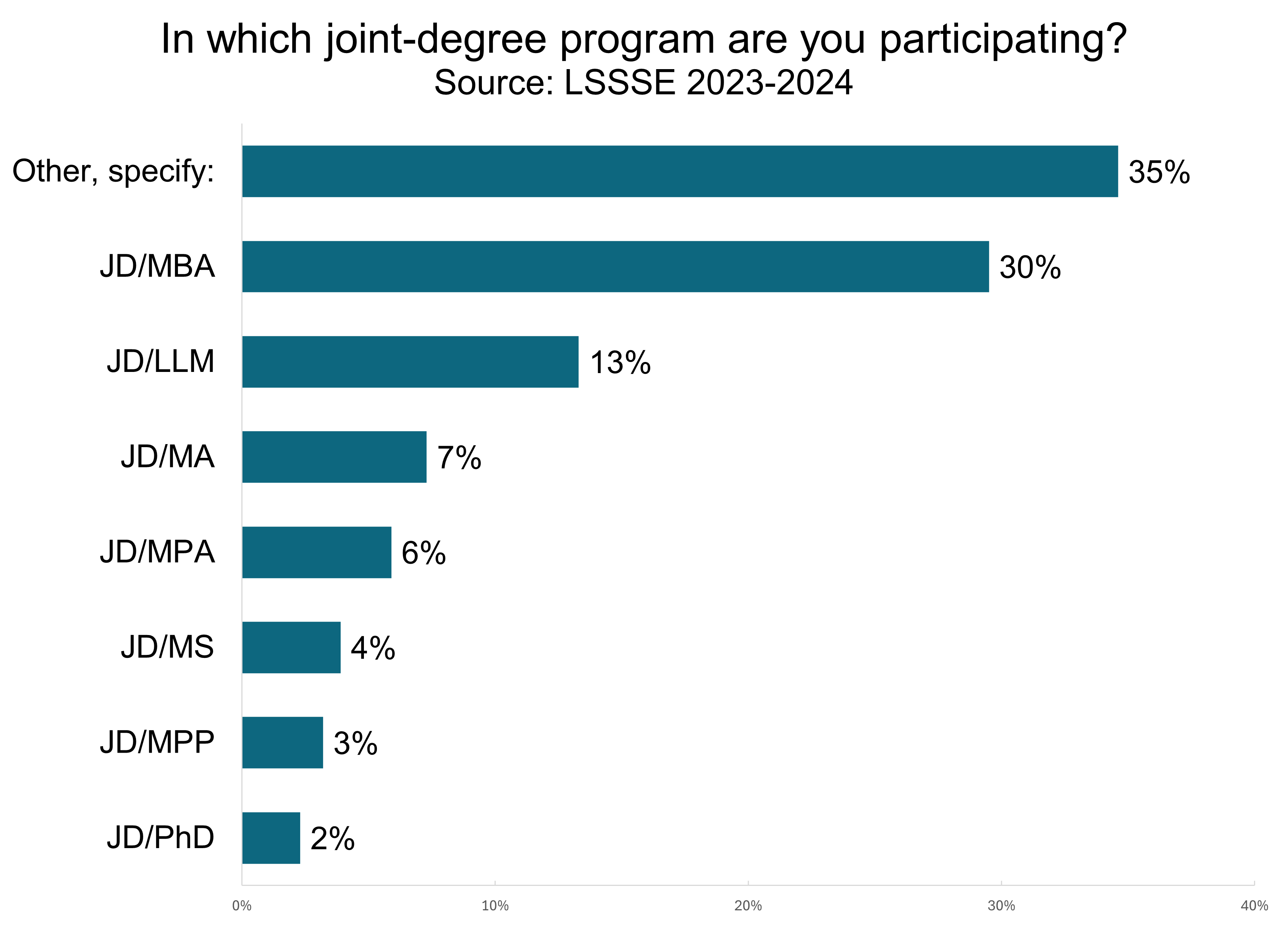

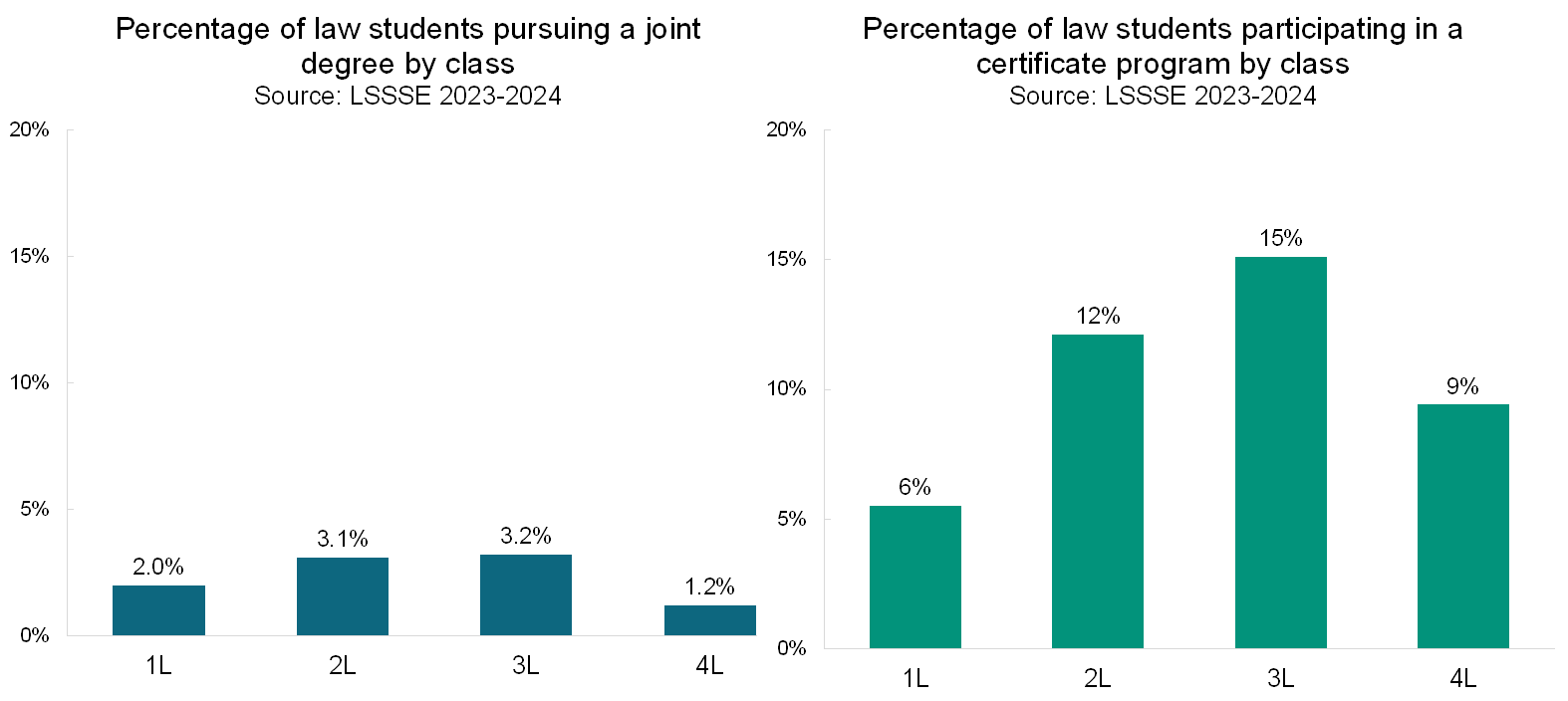

Just under three percent of LSSSE respondents were completing a joint degree in 2023 and 2024. Joint degree programs are often quite specific to the unique offerings of a particular law school. In fact, the most popular joint degree program on the survey is “Other, specify.” Of the LSSSE-provided options, the combined JD/MBA is by far the most popular choice among joint degree students (30%), followed by the JD/LLM (13%), the JD/MA (7%), and the JD/MPA (6%). Only 2% of joint degree students are pursuing a JD/PhD.

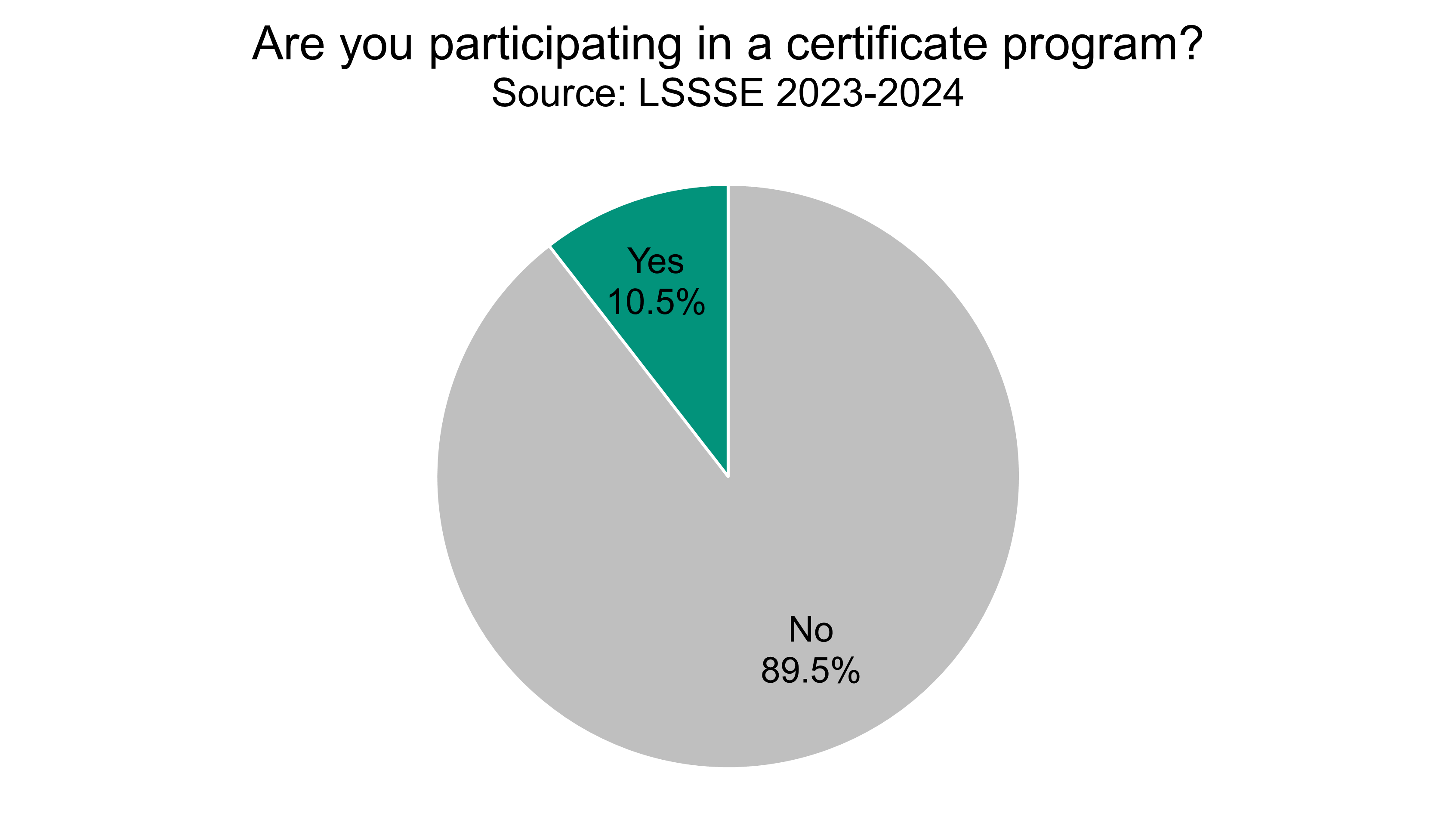

Certificate programs can provide additional content knowledge without the commitment of another entire degree, which makes them a somewhat more popular option. Nearly 11% of LSSSE respondents were pursuing a certificate in 2023 and 2024. The most common certificate program specializations included Health Law, Intellectual Property Law, Business Law, and Environmental Law.

Law students appear to add on certificates as they progress through law school. Only 6% of 1Ls were pursuing a certificate, but among 3Ls, that number rose to 15%. It may be that 1L students do not realize the value, availability, or relative ease of completion of certificates during the course of completing their law degrees and only add them on once that has been made clear to them. This may signal that law schools could advertise their certificate offerings more clearly to prospective and incoming students. Interestingly, there is also a small difference in the percentage of students who are pursuing joint degrees across their years in law school. Around 2% of 1L students were completing a joint degree, compared to 3.2% of 3L students.

By completing joint degree programs and earning certificates, law students can demonstrate their commitment to interdisciplinary learning and their ability to integrate legal principles with other subject areas. These students ultimately enhance their versatility and effectiveness as practitioners in a complex legal landscape.

By completing joint degree programs and earning certificates, law students can demonstrate their commitment to interdisciplinary learning and their ability to integrate legal principles with other subject areas. These students ultimately enhance their versatility and effectiveness as practitioners in a complex legal landscape.

Learning to Think Like a Lawyer

Learning to think like a lawyer is crucial for developing essential analytical skills and a nuanced understanding of legal principles. This process involves honing the ability to critically assess legal issues, construct persuasive arguments, and anticipate counterarguments. Learning to think like a lawyer is challenging because it requires a shift in mindset and the development of complex analytical skills. Law students must master intricate legal concepts and apply them to varied contexts, often under pressure. This involves not only understanding the law but also critically analyzing case precedents and identifying subtle distinctions. Additionally, the emphasis on precision in language and argumentation can be daunting, as even minor errors can significantly impact legal outcomes. By the time they are ready to graduate, most law students have learned to cultivate a mindset that prioritizes logical reasoning and ethical considerations, which are vital for effective advocacy. Ultimately, mastering this way of thinking not only prepares students for successful careers in law but also equips them to navigate complex societal issues with integrity and insight.

LSSSE provides a Learning to Think Like a Lawyer (LTTLL) Engagement Indicator that is a succinct metric for understanding the degree to which students are engaging in this learning process. The LTTLL Engagement Indicator combines several individual survey questions that are statistically and conceptually related to one another. This makes Engagement Indicators meaningful for comparisons because they reduce the risk of relying too heavily on any individual survey question. The LTTLL Engagement Indicator combines the following questions from the main LSSSE survey:

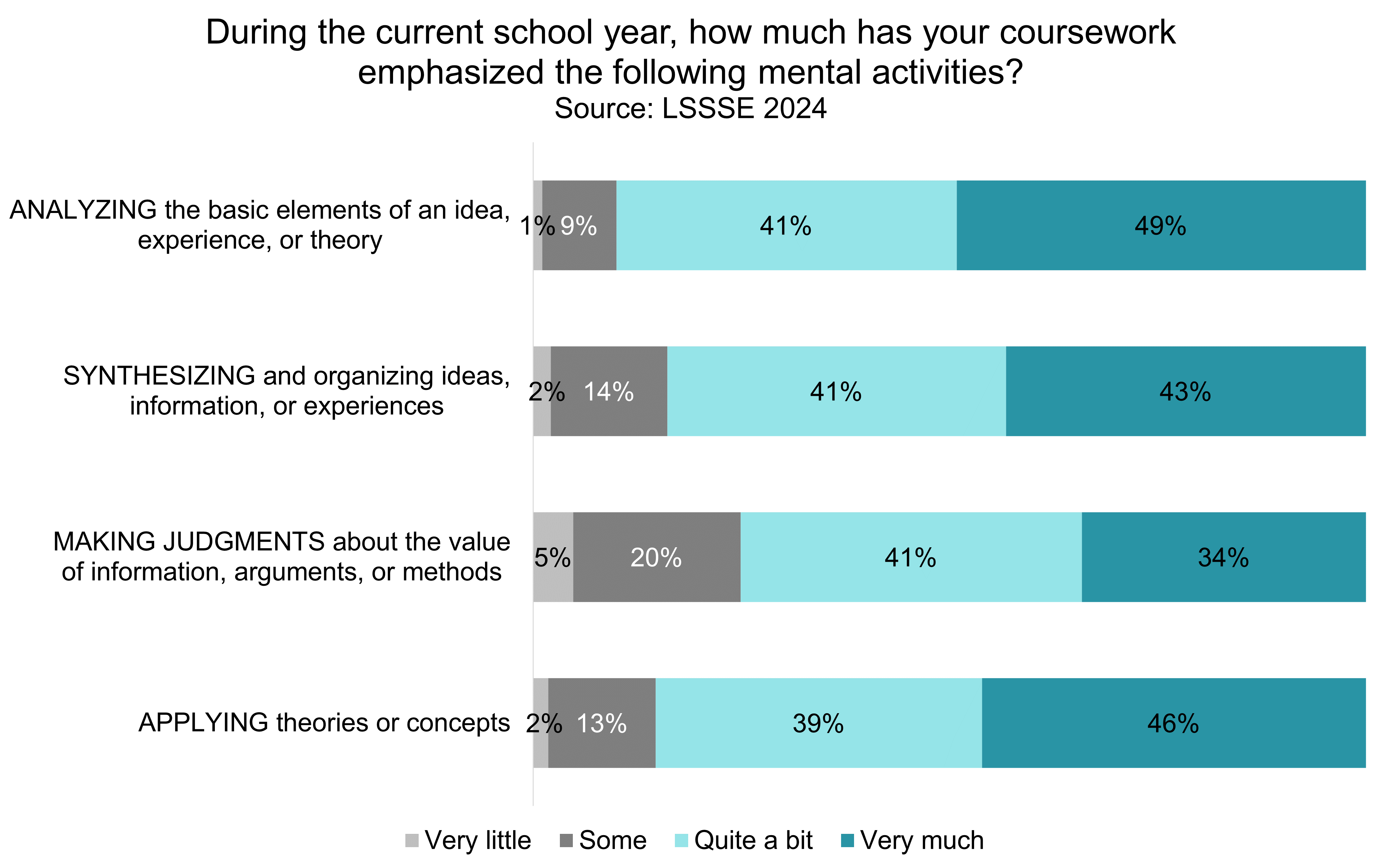

During the current school year, how much has your coursework emphasized the following mental activities?

- Analyzing the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory, such as examining a particular case or situation in depth, and considering its components

- Synthesizing and organizing ideas, information, or experiences into new, more complex interpretations and relationships

- Making judgments about the value of information, arguments, or methods, such as examining how others gathered and interpreted data and assessing the soundness of their conclusions

- Applying theories or concepts to practical problems or in new situations

The response options are “very much,” “quite a bit,” “some,” and “very little.”

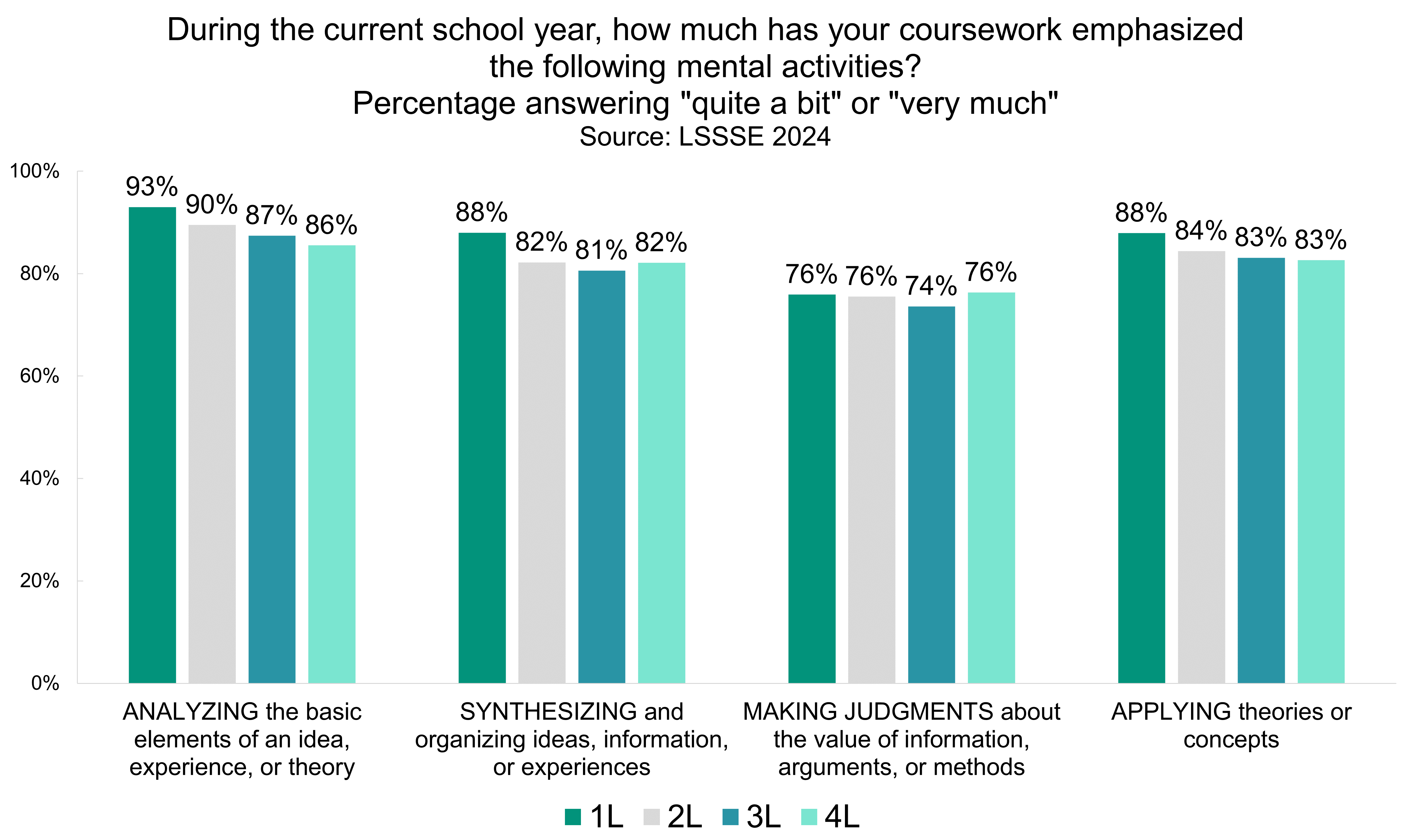

Of the four cognitive activities, students are most heavily engaged in analyzing the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory. Ninety percent of law students do this often or very often. Next comes applying theories or concepts to practical problems or in new situations (85%) and synthesizing and organizing ideas, information, or experiences into new, more complex interpretations and relationships (84%). Three-quarters (75%) of law students frequently make judgments about the value of information, arguments, or methods, such as examining how others gathered and interpreted data and assessing the soundness of their conclusions.

There are some interesting differences in how students respond to these questions across class years. 1L students are more likely to frequently engage in all the LTTLL mental activities compared to 2L and 3L students. For example, 93% of 1L students frequently analyze the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory, compared to only 86% of 3L students. Generally, 1L students are somewhat more engaged with the law school experience and more enthusiastic overall relative to their more seasoned peers, so that might explain this discrepancy. However, it is also possible that 3L students have become so fluent with these processes that they do not necessarily note them in isolation from the type of legal thinking which has become automatic to them.

By applying legal theories and concepts to real-world scenarios, aspiring lawyers learn to navigate the intricacies of the law, develop strategic approaches, and ultimately advocate effectively for their clients. This comprehensive skill set is essential for rigorous legal thinking and practice. LSSSE provides customized tools to gauge how well your students are learning these crucial mental processes as well as ways to compare your students to selected peers and national averages. Contact us to learn more.

Artificial Intelligence and JD Students

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the ability of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as reasoning, learning, or decision making. AI has been applied to various domains, including law, where it can assist in research, drafting, analysis, or prediction. However, the use of AI in the law is certainly not without controversy, particularly given the high-profile and embarrassing incidents in which lawyers who had not properly vetted their AI bot’s research included AI hallucinations in court filings.

Institutions of higher education are currently grappling with the question of whether artificial intelligence is an essential tool of the future workforce or a means by which students may attempt to bypass their own educational enrichment and critical thinking skill development. We wanted to know how often JD students are currently using AI in their law school coursework. In 2024, LSSSE added the following question:

How often do you use AI (ChatGPT or similar technology) to help prepare for class or complete class assignments, projects, exams, or papers?

- Never

- Sometimes

- Often

- Very often

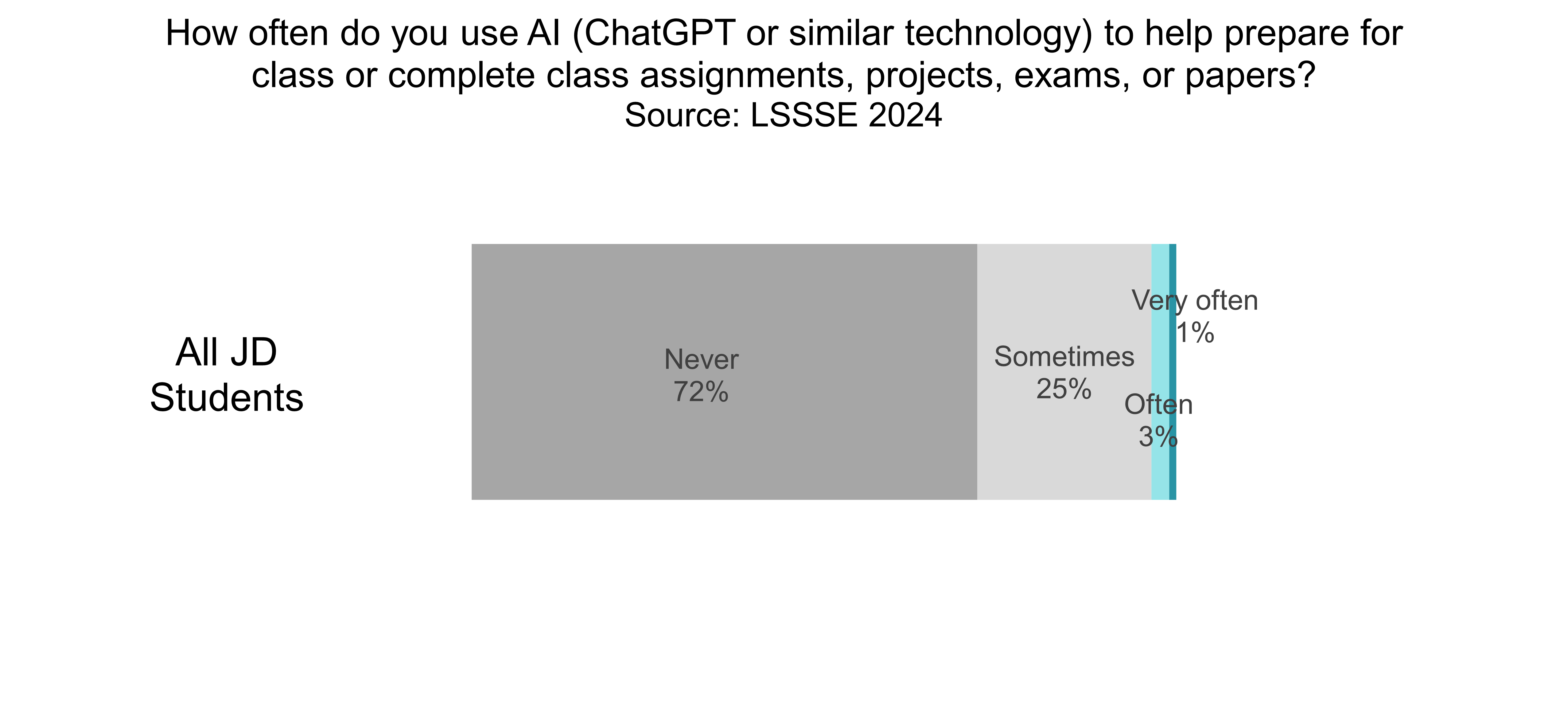

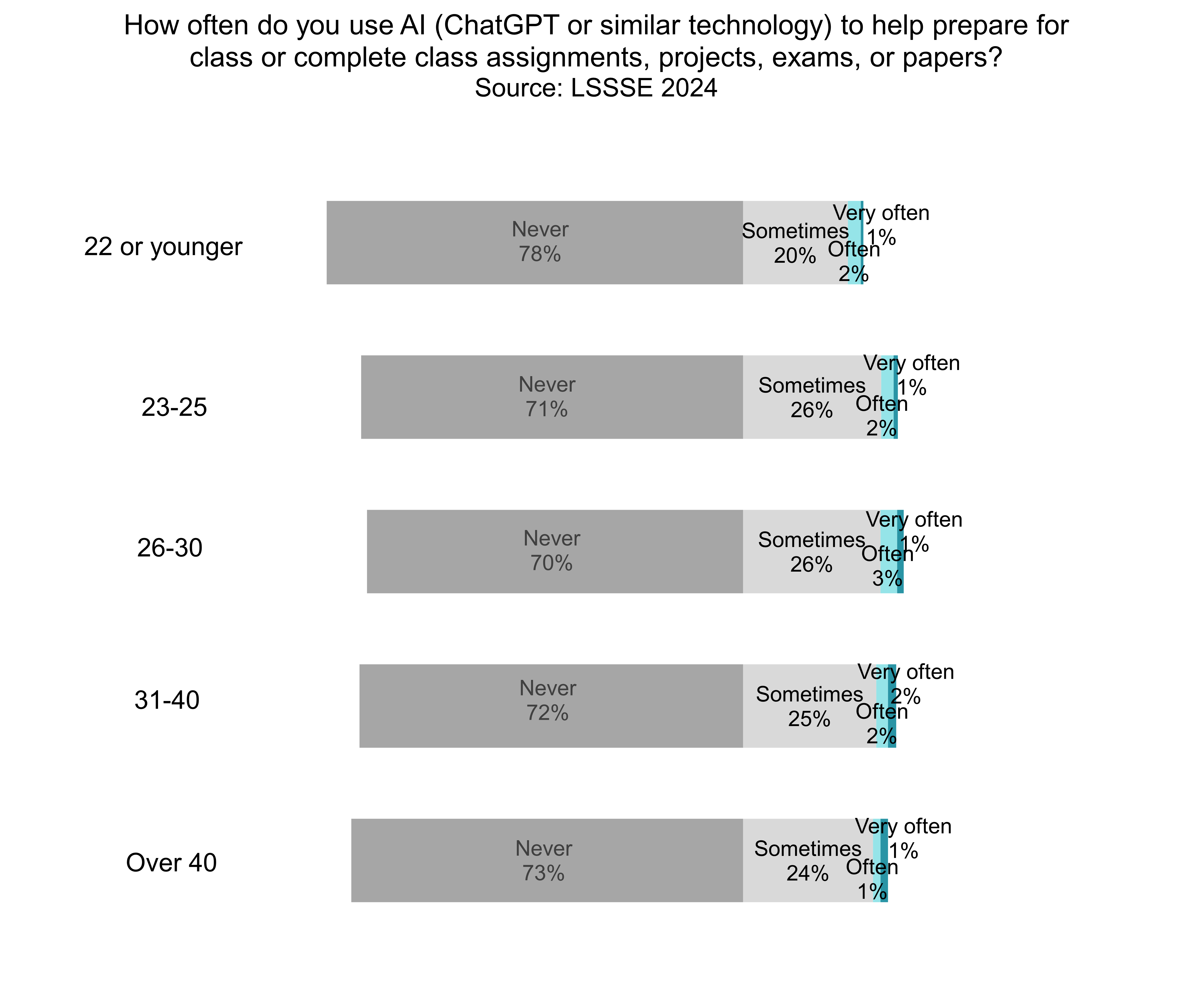

Our analysis shows that most law students are not currently using AI in their coursework at all. Almost three-quarters (72%) never use AI to prepare for class or complete assignments. A quarter of law students (25%) sometimes use AI in their coursework, and only 4% use it often or very often.

There are only slight generational differences in AI usage, with students in the 23-30 age group a perhaps a tiny bit more likely to use AI than other students. Interestingly, law students who are 22 or younger are the least likely age group to use AI for class preparation or assignments, with only 22% doing so at least sometimes.

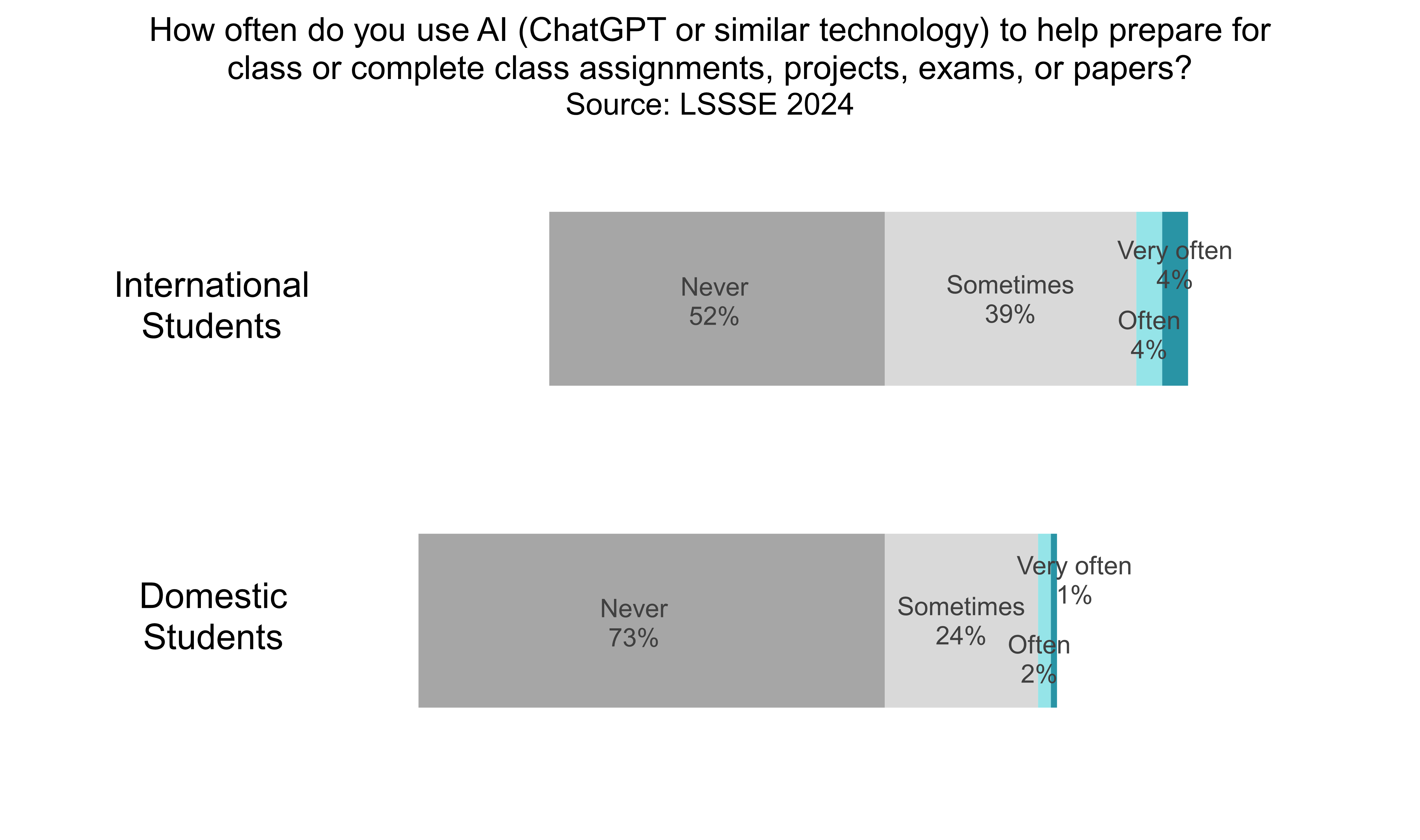

However, international law students are much more likely than domestic law students to use AI for their law school coursework. Almost half of international law students (48%) use AI at least sometimes compared to only 27% of domestic law students. This parallels a larger trend in undergraduate education in which U.S. college students are much less likely to use AI than their counterparts elsewhere in the world. International students attending U.S. law schools who speak English as a second language may be drawn to AI because of the ways it can be harnessed to support the unique needs of multilingual students, particularly in decoding complex texts. Whether AI usage for this or any other purpose is necessarily desirable remains to be seen, although it is useful to note that students are already accessing and using these tools.

AI usage among law students in the U.S. is currently quite low, with most students never using it for their coursework. There are some variations by age and nationality, particularly with international law students using AI tools at a much higher rate than domestic law students. Law schools would be wise to pay attention to both the potential benefits of AI for legal research and writing, as well as the challenges and limitations of AI in the legal domain. LSSSE will continue to track AI usage to understand the degree to which law students are using these tools in their pursuit of learning and understanding the law.

Law Students Working Harder Than They Thought Possible

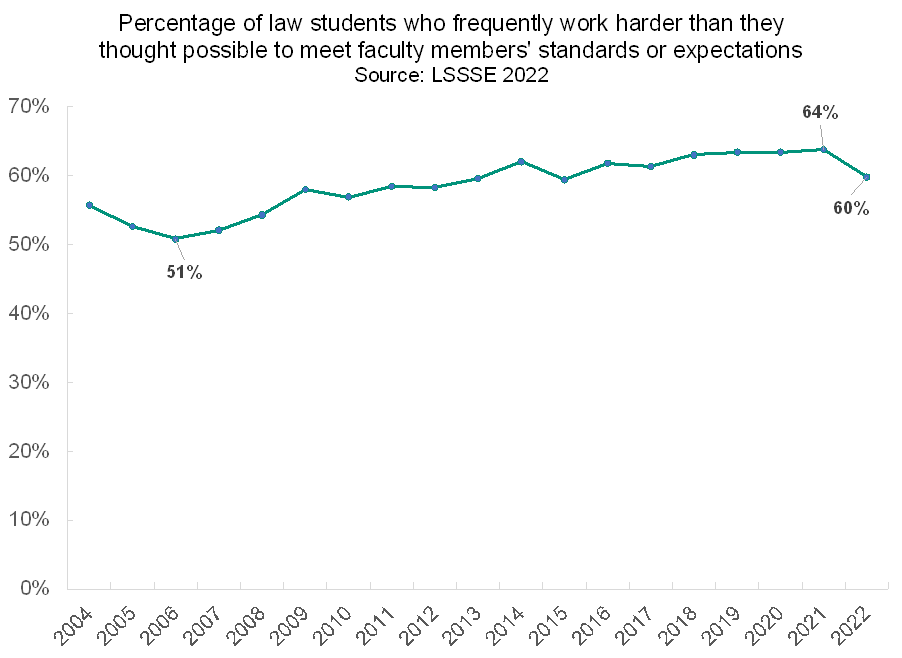

Faculty hold law students to high standards. In 2022, 60% of law students frequently worked harder than they thought possible to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations. This number has generally trended upward over the last twenty years, although the lowest recorded percentage of students frequently working harder than they thought possible was still a respectable slight majority (51%) in 2006. In 2022, only 8% of students never worked harder than they thought possible.

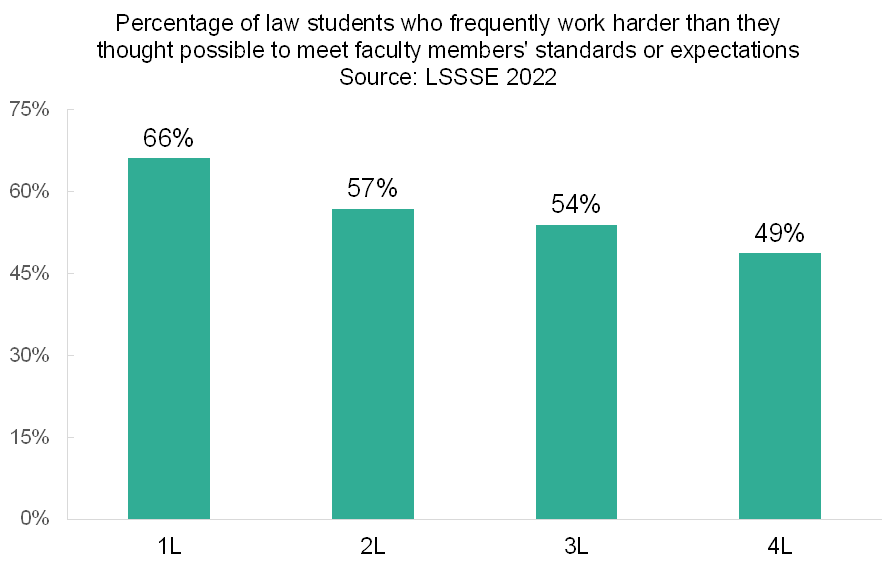

Somewhat unsurprisingly, students who are new to law school are more likely to push themselves to their limits than students who are accustomed to law school life. Two-thirds (66%) of 1L students frequently work harder than they thought possible compared to 54% of 3Ls and 49% of 4Ls. Perhaps new law students are particularly eager to prove themselves to their professors and peers or perhaps more senior students are accustomed to the way that the law school curriculum draws out their best performance and thus already know exactly how hard they can work.

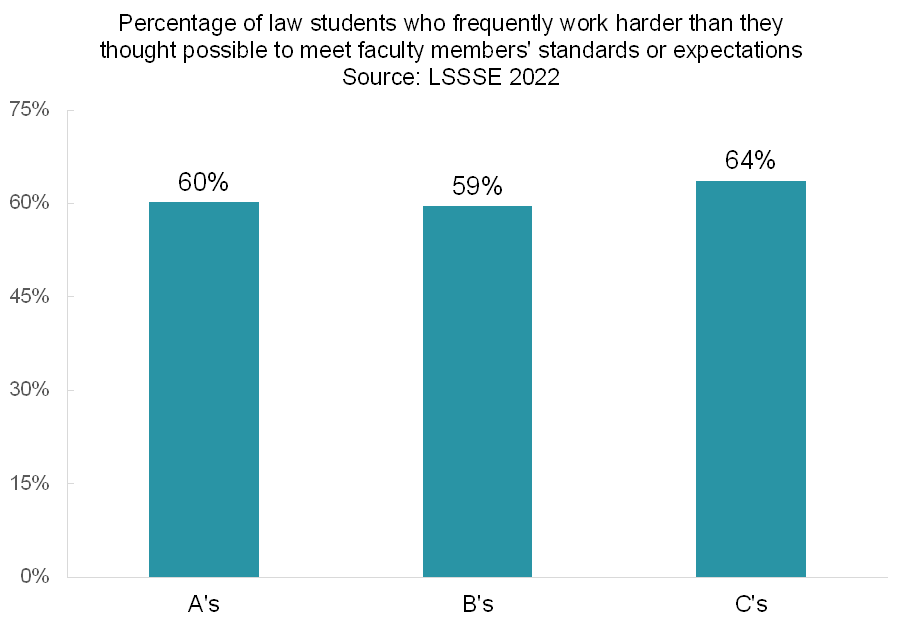

Interestingly, students who generally achieve C grades in law school are more likely to frequently work harder than they thought possible compared to students who achieve mostly A’s and B’s. This may indicate that degree of effort is not always accurately reflected by scores on papers and exams for some students.

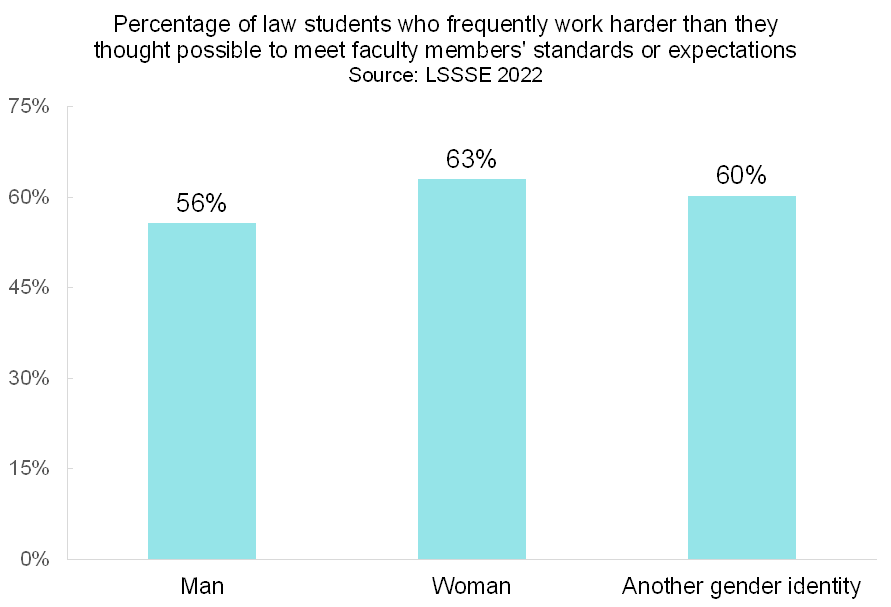

Finally, there are gender differences in the percentage of students who surprise themselves with the intensity of their efforts. Sixty-three percent of women frequently work harder than they thought possible to meet faculty standards or expectations compared to 56% of men. People with another gender identity fall in between at 60%. Ten percent of men and people with another gender identity never work harder than they thought possible compared to only 7% of women.

The data are clear that attending law school is a challenging and demanding endeavor. Most students rise to the occasion by pushing themselves to do their best work in order to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations. Hopefully these efforts are counterbalanced by supportive law schools who also foster good self-care and community care practices for budding legal professionals.

Providing the support law students need to succeed academically

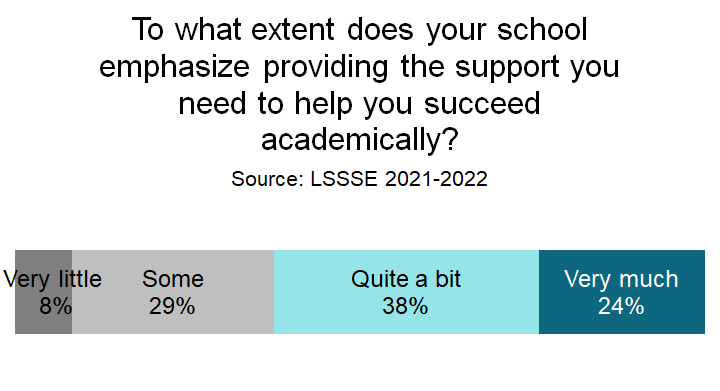

A strong academic program is the foundation of any law school. Equally important is that law schools provide the support services students need to meet the rigors of the curriculum. About two-thirds of law students feel that their law school places “quite a bit” or “very much” emphasis on providing the support they need to succeed academically.

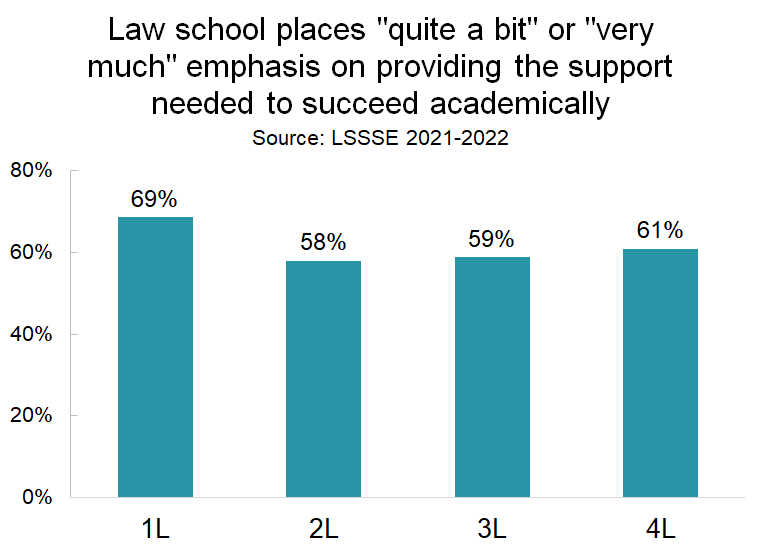

1L students are more likely to feel supported than their more advanced colleagues. Although the general optimism and positivity that 1L students feel toward their experience tends to steadily decline with advancing years for any measure of engagement, for the perception of academic support, satisfaction drops markedly among 2L students and then remains at that level during 3L and 4L years. This suggests that there is an initial sense of being supported that fades fairly quickly after students adjust to their new environment.

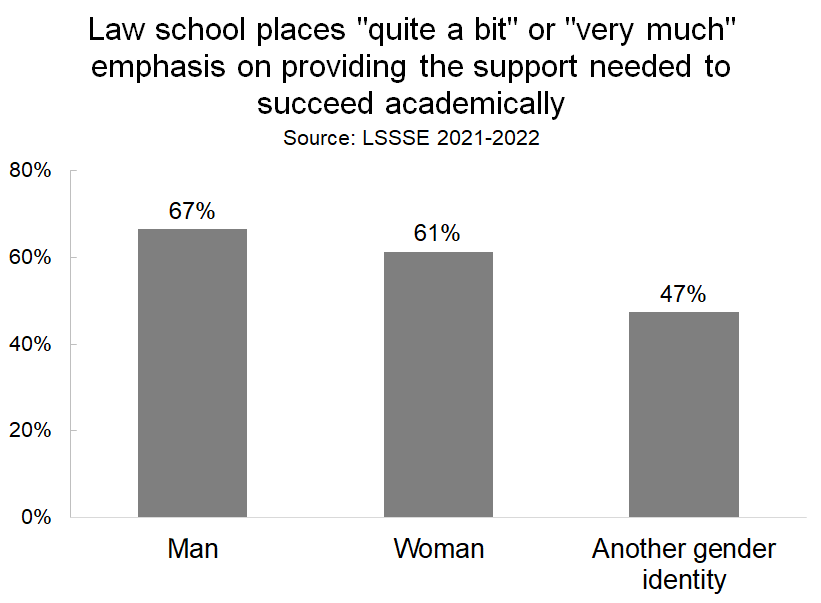

Two-thirds of men feel that their law schools places a strong emphasis on supporting academic success, which is slightly higher than the proportion of women who feel similarly (60%), but fewer than half of the people who have another gender identity feel that level of academic support.

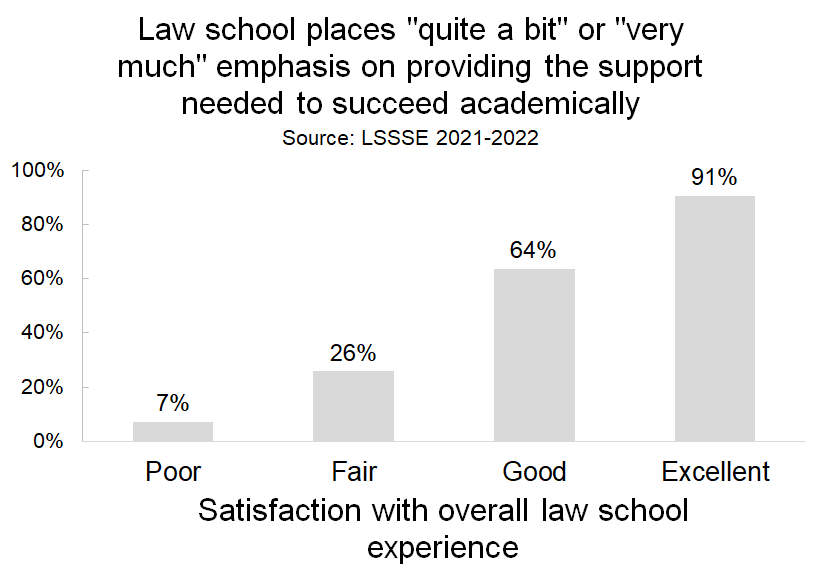

Importantly, the degree to which students feel academically supported is very strongly correlated with whether they are satisfied with their overall law school experience. A full 91% of students who rate their experience as “excellent” feel supported in their academic success compared to only 7% of students who have are having a “poor” experience.

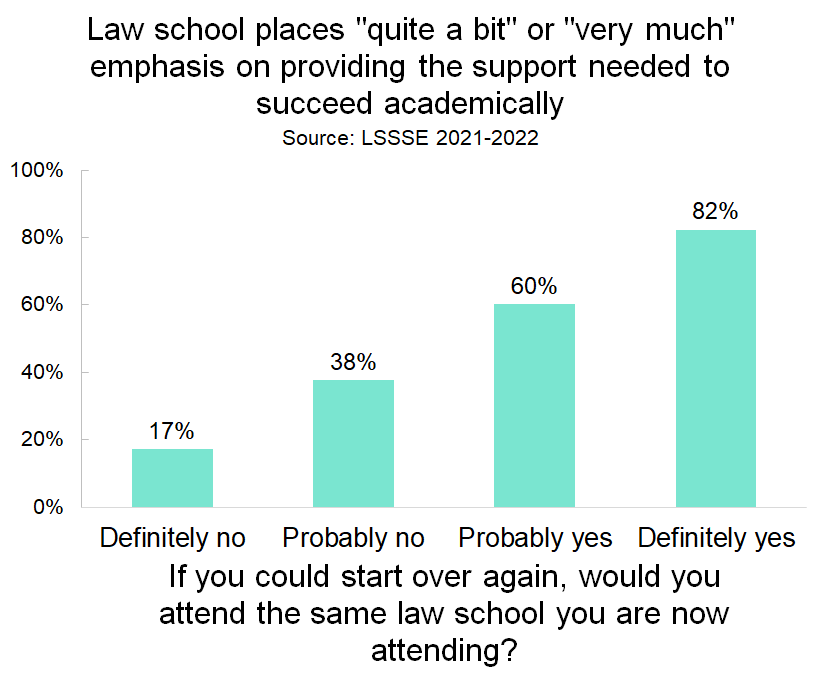

Perceived degree of academic support is also closely tied to whether a student would choose their law school again if they could start over, although the relationship is slightly less stark than for overall law school satisfaction. Among students who would either probably not or definitely not attend the same school, about 32% feel supported to succeed academically. But among students who would probably or definitely attend the same school, 70% feel academically supported.

Law students are driven to succeed in the face of the challenges presented by their academic program. Students who feel supported in their academic endeavors by their schools are more likely to be satisfied with their overall experience and to say that they would choose the same school if they could start over. Academic support is integral to a successful law school experience and likely impacts students’ long-term satisfaction and likelihood to become alumni who speak highly of their alma maters.