Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Erika K. Wilson

Professor of Law, Wade Edwards Distinguished Scholar, and Director of the Critical Race Lawyering Civil Rights Clinic

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 143 S. Ct. 2141 (2023) arguably ended race-conscious admissions policies as we know them. While the Court did not expressly overrule diversity as a compelling state interest, it did find that the way in which Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were using race to achieve diversity was unconstitutional. The majority opinion observed that universities undermined their stated interest in obtaining a racially diverse class by relying upon “opaque racial categories.” It identified as particularly problematic categorizing all Asian applicants together with no distinctions made between South and East Asians; the arbitrariness of the Hispanic categorization; and the under inclusiveness of the Middle Eastern classification. Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion made a similar observation with respect to the categorization of Black students:

The “Black or African American” category covers everyone from a descendant of enslaved persons who grew up poor in the rural south, to a first-generation child of wealthy Nigerian immigrants, to a Black-identifying applicant with multi-racial ancestry whose family lives in a typical American suburb.

Gorsuch’s critique is salient because the original purpose of race-conscious affirmative action programs was to remediate the multi-generational effects of slavery and the afterlives of slavery. Yet, as documented by legal scholars like Angela Onwuachi-Willig, in the early 2000s Black students at elite universities were overwhelmingly mixed-race students, or first- or second-generation Black Americans, meaning their parents and/or grandparents were immigrants. Lani Guinier and Henry Gates raised concerns in 2004 because only one-third of Harvard’s Black undergraduate students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America, descendants of persons enslaved in America.

Recent research by Kevin Brown and Kenneth Dau-Schmidt relying on LSSSE Survey data shows that not much has changed since the early 2000s. Similar patterns of disproportionate representation of what Brown and Dau-Schmidt call “ascendant Blacks” (those with two American-born Black (non-biracial) parents) exists in law school enrollment today. The data show three noteworthy trends:

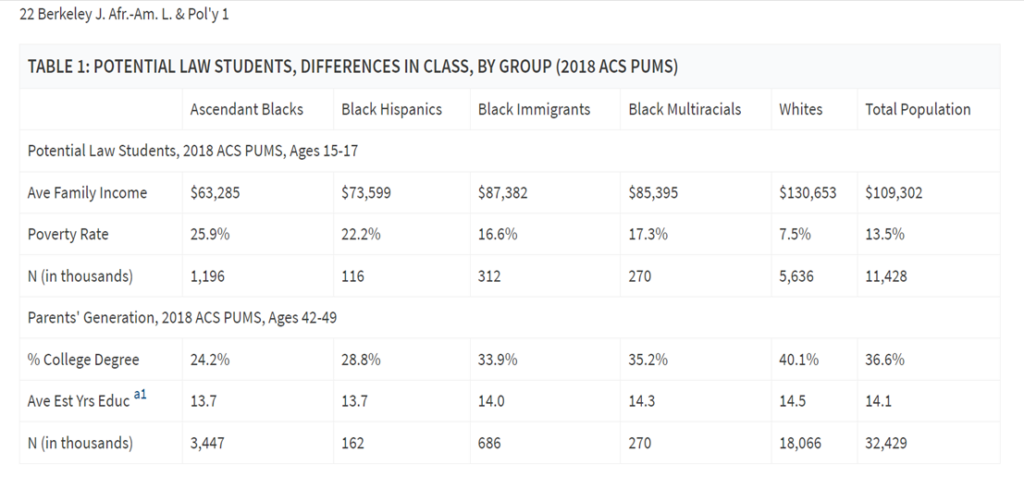

First, while structural racism impacts all Black people in America, it impacts some groups more acutely. As they write in their article, ascendant Black law students have lower average family incomes, higher poverty rates, and are less likely to have parents with a college degree.

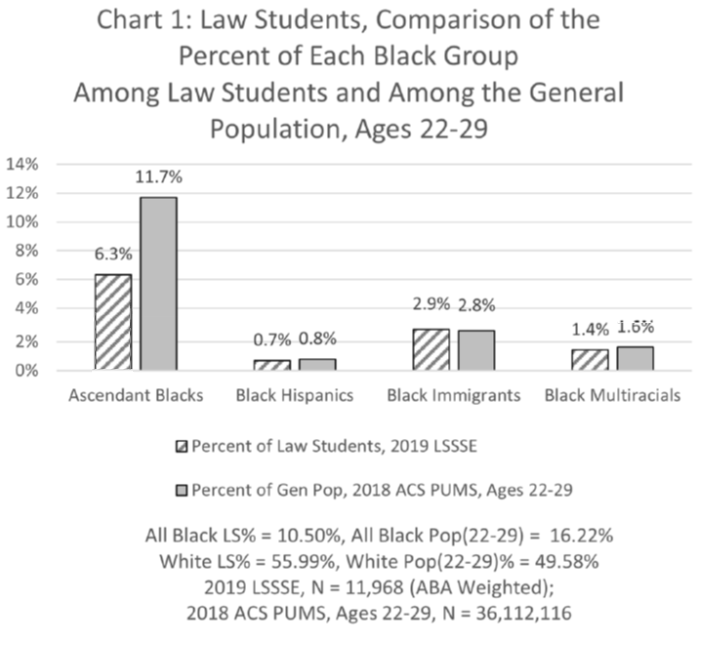

Second, all Black people, except Black Immigrants (defined as Black people with at least one parent not born in America), are underrepresented among law students; furthermore, the extent of underrepresentation is much worse for ascendant Black law students than for other Black law students.

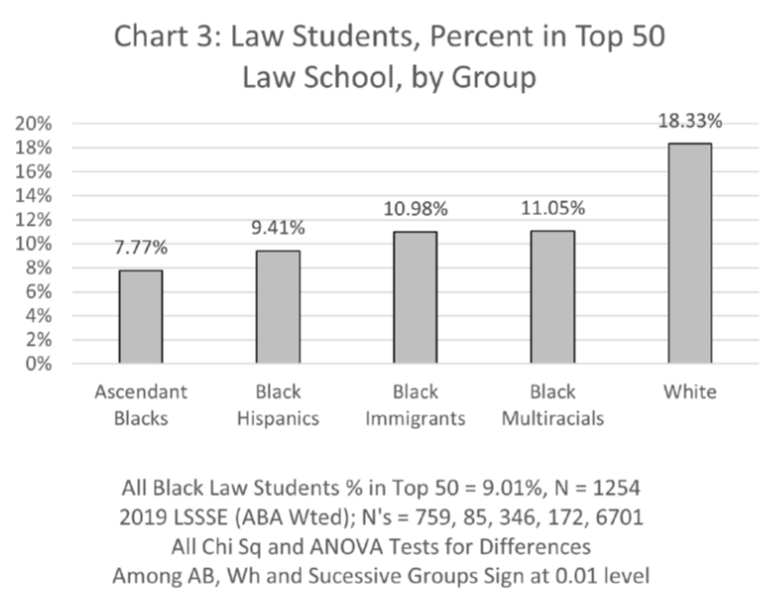

Third, ascendant Black law students are underrepresented at Top 50 law schools relative to their representation within the population of Black people in America, and relative to all other groups of Black law students.

The data and their implications should inform the path universities take to reinvent their affirmative action programs. Diversity is still recognized as a compelling state interest. Universities can and should fashion admissions programs that seek to increase representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. To be sure, they should also continue to make efforts to increase representation of all Black groups because race remains a salient and undeniable barrier for all Black people in America. Yet the unique burdens and history of subordination linked directly to American slavery imposes a special remedial obligation on universities to provide access to Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. This is especially true for elite universities such as Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that directly benefited from slavery.

In Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in Students for Fair Admissions, he offers a potential Constitutional path for doing so. He suggests that a classification consisting of descendants of persons enslaved in America is not a racial category. He contends that:

[The 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Act ] applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not [B]lacks writ large. And, because “not all [B]lacks in the United States were former slaves,” “ ‘freedman’ ” was a decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.

His comments, as other scholars have noted, raise questions as to the legality of an affirmative action program centered on descendants of persons formerly enslaved in America, as such a categorization may not be subject to the same level of heightened scrutiny as a race-based classification. Nonetheless, Thomas’ assertion that “freedmen” was not a racial categorization is admittedly dubious. But such a targeted program might also be justified under the remedial justification for race conscious policies. Thus, universities should take Thomas seriously. They should fashion admissions programs aimed at increasing the representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. LSSSE data and history demonstrate the normative case for doing so.