Guest Post: LSSSE Data Illustrates Public Service Intent Among Asian American Law Students

Aryssa Ham

Undergraduate Researcher

University of California, Davis

Public Service Intent Among Asian American Law Students

What drives people to set aside their personal interests to help the collective? In 2017, Yale Law School and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association found that Asian Americans gravitate towards careers in law firms and business over the public sector more than any other racial group, with few Asian Americans citing a desire to enter government as motivation to attend law school (Chung et al. 2017). Prior studies on the underrepresentation of racial minorities within the legal field often point to lack of academic or financial support as barriers to public service; yet Asian Americans were found to be the highest earning racial group in the U.S. and were overrepresented in top law schools (Sabharwal & Geva-May 2013; Kochhar & Cilluffo 2018; Chung et al. 2017).

This prompts a string of questions: Why are Asian Americans drawn to the private sector of the legal field? Why are they underrepresented in government and public interest? Alternatively, do Asian Americans prefer other forms of public service, such as pro bono work? If so, why doesn’t any other racial group appear to parallel this preference?

Despite past studies noting a weaker interest in the public sector among Asian Americans, few delve into potential explanations or examine variances among ethnicity. The original rallying, pan-ethnic Asian American identity has become a racial label that eclipses meaningful differences, propagating the Model Minority stereotype (Wu 2014:246). This social construct manifests in overlooked outcome disparities within the Asian American community, thus making ethnicity especially critical to examine.

As an undergraduate studying both psychology and sociology, I began an honors thesis last summer that integrates my majors: taking career decisions—a private, subjective experience—and zooming out to explore how these decisions interact with how society is organized and maintained. In my thesis, I study the professional trajectories of Asian Americans within the legal field—particularly the factors that determine whether and when an individual enters, stays, or switches into the public or private sector. Ultimately, I aim to shed light on why the legal profession is an underused entryway into government for Asian Americans, while simultaneously revealing the contrasting stories that vary by ethnicity.

Why LSSSE data?

I examine the extracurricular activities of law students to uncover patterns among students exhibiting public service motivation before fully entering the legal field. Although students can enter law school at different points in their life, I treat law school extracurriculars as the first major professional fork between the public and private sector.

While LSSSE data on student pro bono experiences are publicly accessible, ethnicity data are not shared on the website. After reaching out to Professor Meera Deo and LSSSE, they graciously provided the 2019 analyses that I needed.

I looked at 3 LSSSE Questions:

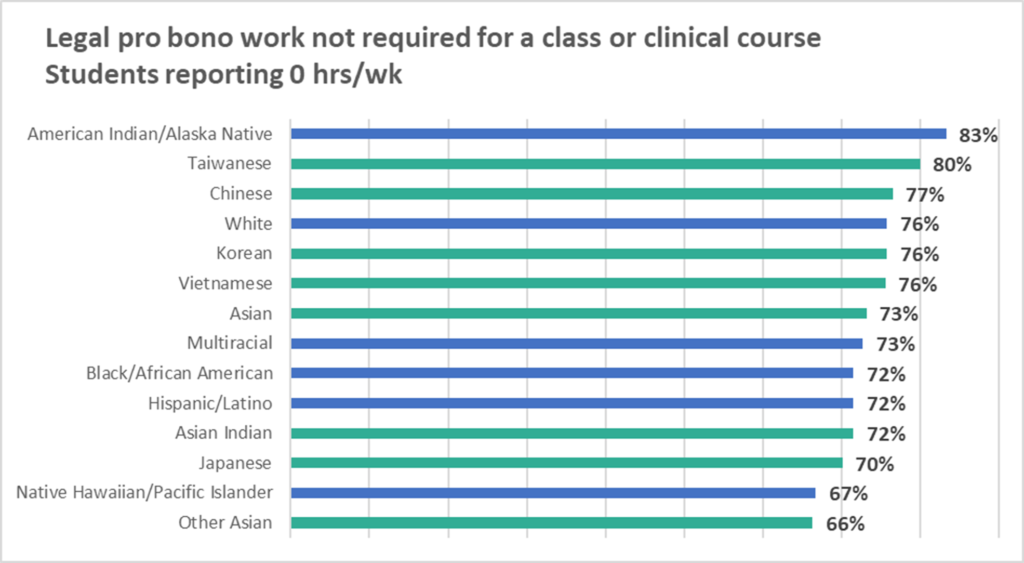

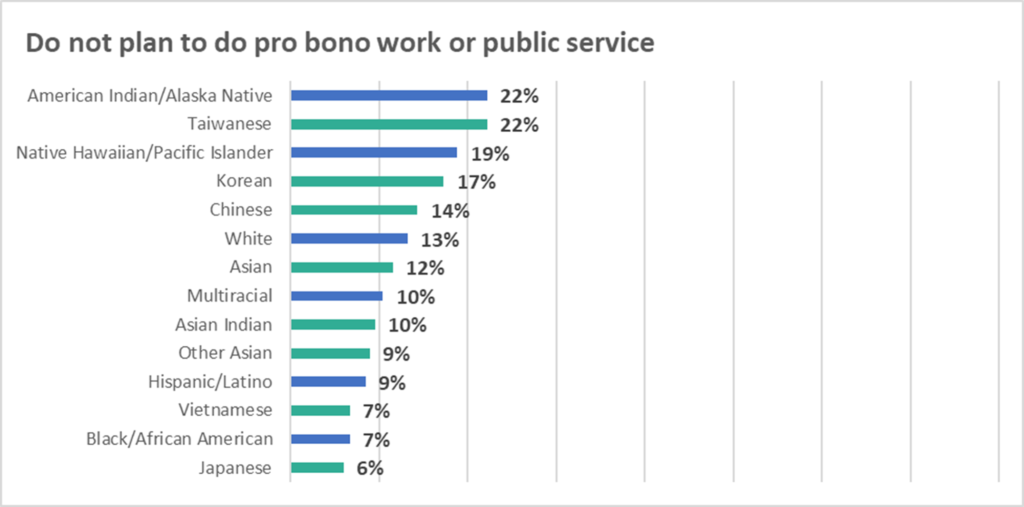

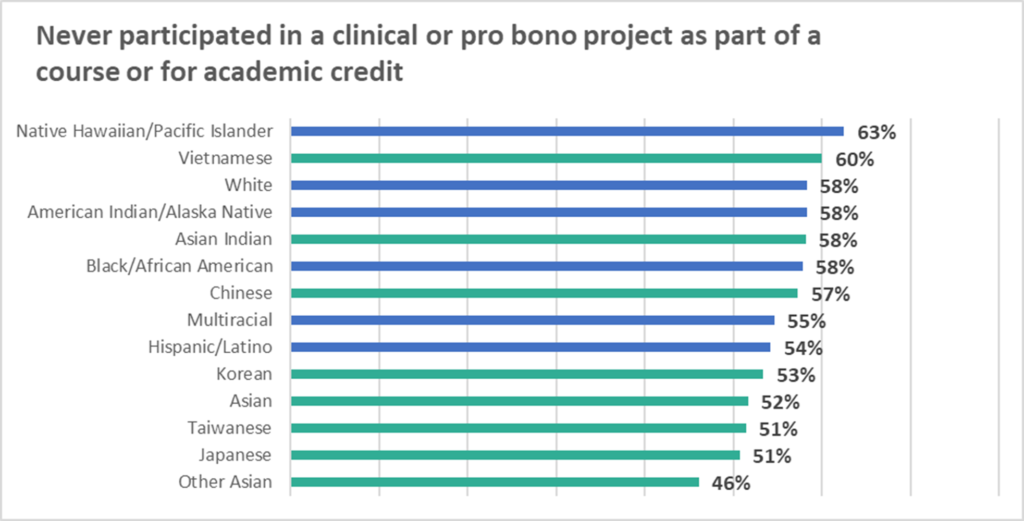

The first question (Pro Bono) asked for the number of hours a student spends each week doing legal pro bono work not required for a class or clinical course. The second (Public Service) asks if a student has done or plans to do pro bono work or public service before graduation, with response options "undecided," "do not plan to do," "plan to do," or "done." The final question (Clinical Project) asks how often a student has participated in a clinical or pro bono project as part of a course or for academic credit, with response options ranging from "never" to "very often."

Here’s what I found:

Pro Bono: Asian ethnicities with greater proportions of participation in pro bono work tend to be those with higher than national median incomes and better representation as elected officials, with four Japanese Americans and five Asian Indian Americans currently holding office in U.S. Congress, while other Asian ethnicities, such as Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, or Vietnamese American, include one to two representatives, if at all. Other Asian, Japanese, and Asian Indian have the lowest proportion of students responding with "0 hours/week."

Public Service: While this question tracks progress from 1L to 3L, the graph echoes the results of Pro Bono, with Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese American students being the only Asian ethnic groups with a higher proportion of “do not plan to do” than white students.

Clinical Project: The proportion of Asian Americans who have participated is the highest among all races. When broken down by ethnicity, Other Asian, Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean American have the lowest proportion of “never” responses. On the other end, proportions of Asian Indian Americans reporting “never” (58.2%) most closely mirrors those of white students (58.3%). Finally, Vietnamese Americans have the highest proportion aside from Hawaiian/Pacific Islander reporting “never,” but they also have the second-highest proportion reporting “very often,” only behind Other Asian.

Note: The “Other Asian” label is large, with a sample size more than doubling three of the six other reported Asian ethnicities. Ideally, a Filipino category would have been useful among the ethnic breakdowns, as Filipino Americans constitute the third largest proportion of Asian Americans.

Main Takeaway

The findings reiterate how the Model Minority stereotype harmfully obscures the needs of many Asian Americans. Although the proportion of Asian Americans who contribute pro bono work is lower than other racial minorities and higher than white students, Asian ethnicities with fewer structural constraints (e.g., higher national median income, greater government representation) contribute a greater proportion of pro bono hours than Black and Latinx students, leaving students of other Asian ethnicities potentially overlooked or under-supported.

This concludes the survey portion of my thesis. To complement the survey data, I am conducting interviews with Asian American lawyers in both the public and private sectors. I hope to code the transcripts for potential public service motivation factors, uncover individual attitudes toward the public sector, and fully explore the linear and nonlinear paths of Asian Americans in law.

Huge thanks to Professor Deo and the LSSSE staff for being incredibly helpful! As an undergrad, I was astonished at how willing they were to accommodate me, and I’m so grateful for their support.

Finally, if anything piqued your interest, please don’t hesitate to contact me at aham@ucdavis.edu.

References

Chung, Eric, Samuel Dong, Xiaonan April Hu, Christine Kwon and Goodwin Liu, Yale Law School & National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, A Portrait of Asian Americans in the Law (2017).

Kochhar, Rakesh, and Anthony Cilluffo. “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians.” Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 12 Jul. 2018, www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/.

Sabharwal, Meghna and Iris Geva-May, “Advancing Underrepresented Populations in the Public Sector: Approaches and Practices in the Instructional Pipeline.” Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19:4, 2013, 657-679, DOI: 10.1080/15236803.2013.12001758

"U.S. Asians Have a Wide Range of Income Levels." Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 8 Sept. 2017, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/ft_17-09-08_asian_income/.

Guest Post: A LSSSE Collaboration on the Role of Belonging in Law School Experience and Performance

Guest Post By Victor D. Quintanilla, Professor at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, co-Director of the Center for Law, Society & Culture

This year is the 15th anniversary of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). In just a short decade and a half, LSSSE has collected over 350,000 law student responses from 200 law schools forming one of the largest datasets that captures law student voices and experiences in law school. My collaborators and I are grateful for the opportunity to share how we harnessed LSSSE’s remarkable dataset to illuminate student experiences with the aim of improving legal education.

This year is the 15th anniversary of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). In just a short decade and a half, LSSSE has collected over 350,000 law student responses from 200 law schools forming one of the largest datasets that captures law student voices and experiences in law school. My collaborators and I are grateful for the opportunity to share how we harnessed LSSSE’s remarkable dataset to illuminate student experiences with the aim of improving legal education.

For the past three years, I have been working with an interdisciplinary team of researchers across several institutions—including Indiana University Bloomington, the University of Southern California, the University of California at Los Angeles, Wake Forest University, and Stanford University—to examine the under-recognized role that psychological friction plays in law school engagement and performance.

Psychological friction can manifest in several ways, including feeling isolated, stereotyped, or feeling that one doesn’t belong (academically, culturally, or socially). These feelings of non-belonging shape the psychological experiences and achievement of students (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2007; 2011). In 2018, in collaboration with LSSSE, we added validated survey items to a pilot LSSSE module to examine students' experiences of belonging, belonging uncertainty, and stereotype threat in law school. Indeed, this kind of collaboration is just one example of the many fruitful ways that researchers interested in studying legal education can work with LSSSE to conduct important empirical research on legal education.

The Role of Social Belonging in the Transition to Law School

All students face challenges in the transition to law school, from developing new friends, to learning the legal concepts and professional skills explored in first-year courses, to building relationships with professors. But law students from disadvantaged social backgrounds, including racial and ethnic minority students and first-generation college students, may wonder whether a "person like me" will be able to belong or succeed in law school and the profession. One consequence is that when disadvantaged law students encounter common difficulties in the critical first weeks and months of law school—such as critical feedback from professors using the Socratic method, difficulty reading cases and materials, difficulty with legal writing exercises, or an absence of feedback—these difficulties can be interpreted as evidence that they may not belong or can’t succeed. This negative inference can become self-fulfilling for all students—and especially for students from disadvantaged social backgrounds.

These worries about belonging and potential are endemic in legal education, occurring at all stages of students’ early legal careers—from the transition to law school, to mastering daunting course material, to the disciplined synthesizing of information required during bar exam preparation.

When students worry that they may not belong in law school, they are more likely to experience anxiety that can interfere with learning and are less likely to reach out to faculty, join study groups, seek out friends, or succeed in the law school environment over time. As such, feelings of belonging may be one important predictor of law school engagement and success.

By analogy, one study with a large group of undergraduate students found that pre-college worries about belonging in college (e.g., "Sometimes I worry that I will not belong in college.") predicted full-time college enrollment the next year, even controlling for high school GPA, SAT-score, fluid intelligence, gender, and other personality differences (Yeager et. al., 2016).

Where do these worries about belonging come from? The quality of students’ social relationships in school is an important predictor of students’ sense of belonging in school (Murphy & Zirkel, 2015; Walton & Cohen, 2007). The quality of students’ social relationships in school shapes students’ experiences and academic outcomes. Students who have strong, positive relationships with peers and professors are more satisfied with their educational experiences, more academically motivated, perform better in school, and are less likely to drop out (Wilcox & Fyvie-Gauld, 2005; Kuh & Hu, 2001).

LSSSE Data Reveals The Importance of Social Belonging in Law School

Our research team adapted validated survey items measuring social belonging and its potential antecedents for the 2018 administration of the LSSSE survey. In this pilot module, over 4,000 students rated their experiences of belonging and belonging uncertainty by responding to items such as, "I felt like I belonged in law school," and "While in law school, how often, if ever did you wonder: 'Maybe I don’t belong in law school?'"

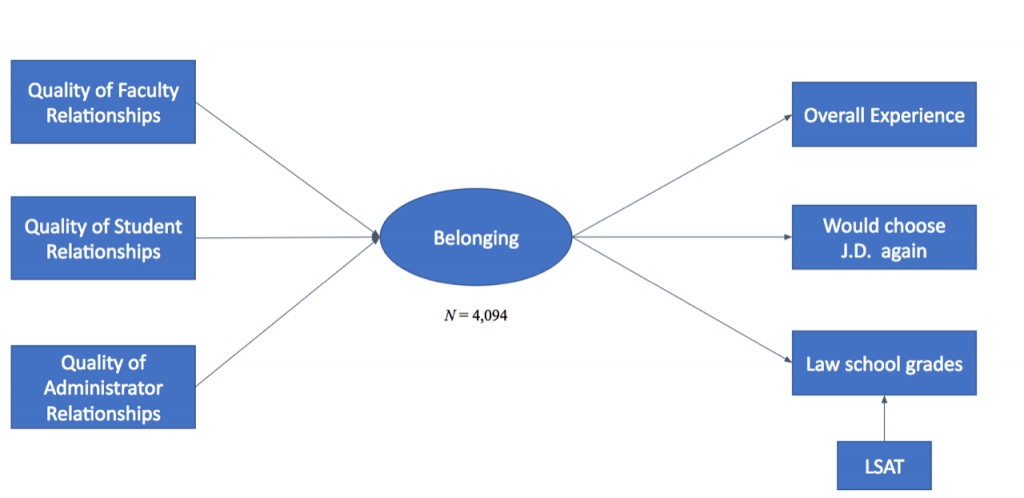

What did we find? First, we found that the quality of relationships with faculty, students, and administrators significantly predicted students’ feelings of belonging in law school. Thus, students’ relationships in law school predict their sense of belonging there.

Did law school belonging predict students’ performance? Yes. Indeed, a sense of belonging significantly predicted students’ overall experience in law school, whether they would choose to go to law school again, and their academic success (i.e., law school GPA) above and beyond traditional predictors such as LSAT scores and undergraduate GPA. Thus, law school belonging is a critical predictor of social and academic success among law students (Quintanilla, et. al, in prep).

Psychological Friction and WISE Interventions

While law schools seek to enhance and maintain student success, an almost-exclusive focus on cognitive predictors of success neglects other important social, contextual, and psychological factors—such as belonging in law school. Using LSSSE data, our research team found that students’ sense of belonging influences their law school satisfaction and grades, above and beyond the effects of LSAT score. We believe that law schools may be fertile grounds for social psychological interventions. "Wise interventions" focus on changing students’ construals of their environment (Walton & Wilson, 2018), and these may improve students’ sense of belonging and academic performance in law school—especially when coupled with changes in some of the structures and practices that dampen relationships and belonging in law school.

We look forward to continuing our collaboration with LSSSE and celebrate the continued growth of empirical legal education research that LSSSE affords. Congratulations to LSSSE on its 15-year anniversary!

*This research program and the design of related interventions are being conducted in collaboration with: Dr. Sam Erman (co-PI, University of Southern California), Dr. Mary C. Murphy (co-PI, IU Bloomington), Dr. Greg Walton (co-PI, Stanford University), Elizabeth Bodamer (IU Bloomington), Shannon Brady (Wake Forrest College), Evelyn Carter (UCLA BruinX), Trisha Dehrone (IU Bloomington), Dorainne Levy (IU Bloomington), Heidi Williams (IU Bloomington), and Nedim Yel (IU Bloomington), and supported by funding from the AccessLex Institute.