Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Jonathan Todres

Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law

Georgia State University College of Law

An unhealthy work-life balance is an all-too-familiar phenomenon in law school, as well as for the legal profession. Mental health and substance use issues have been well-documented in the profession, and a breadth of research shows the detrimental effects of law school on many students’ well-being. All that was true before the COVID-19 pandemic inflicted its double burden—increasing the number of students who are suffering, and exacerbating the extent of harm experienced by those who were already struggling. Of course, there are many underlying causes that demand urgent attention, but an often-overlooked issue is the nonstop work culture of law school that discourages students from taking any time off.

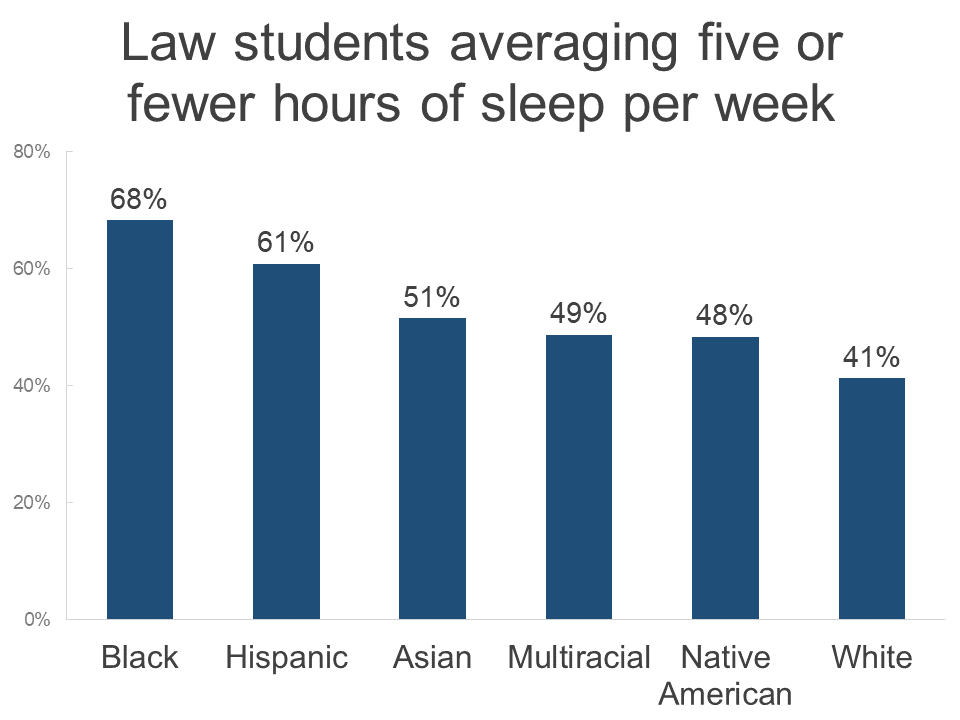

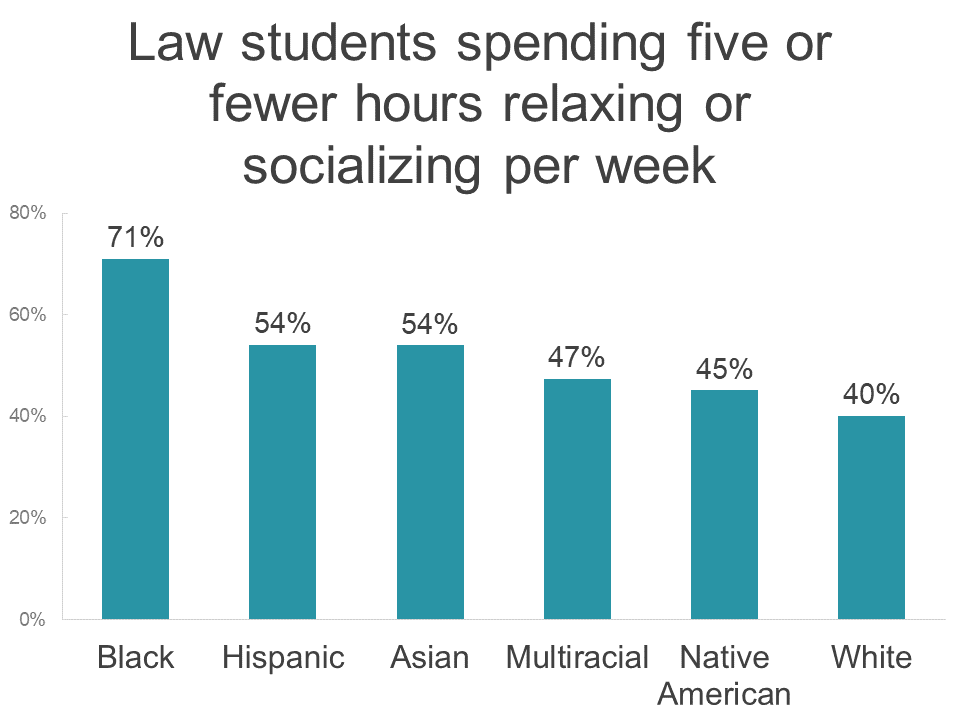

Students need a break. In the 2021 survey administration of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement, nearly half of law students reported averaging five or fewer hours of sleep per night (including weekends). In addition, 43.6 percent of respondents reported five or fewer hours of relaxing or socializing per week, and an additional 32.1 percent reported only 6-10 hours of relaxing or socializing per week. Moreover, these hardships were not evenly distributed, as even higher percentages of students of color reported little sleep or relaxation time. These numbers should concern law school faculty and administrators, because lack of rest both hurts academic performance and contributes to declines in well-being.

If law students are going to achieve and maintain a healthy work-life balance, law schools cannot simply tell students to take care of themselves. Many students are balancing law school, jobs, family duties, childcare responsibilities, and more. This will be true even after the pandemic ends. “Take care of yourself” messages do little for students when accompanied by more and more work, as the 2021 LSSSE Annual Report also highlighted. Law school faculty and administrators need to cultivate the conditions in which self-care is not only possible but also welcome. A key component of that includes enabling students to take time off.

Last spring, I tried to do just that. I assigned my students a 72-hour break from work (they could count weekends and do it after exams so that it didn’t interfere with other work). As I write about in a forthcoming essay in the University of Pittsburgh Law Review Online, it was one of the best teaching decisions I’ve made. Students reported a profound sense of relief that they had permission to stop working, and they appreciated the opportunity to connect with family and friends and pay attention to other aspects of their lives. It bears noting that they also reported feeling guilty for not working. Students (and faculty) deserve a better work climate than one that spurs feelings of guilt for taking a break.

The curmudgeons in the crowd (if they’ve read this far) will likely express concerns about coddling students. My students had already worked hard. They had earned it, but more important, they needed it. Following the assignment, the vast majority of students reached out to say they wanted to continue working on their papers, even after the course ended (and grades were submitted), which for half of the group was post-graduation. In other words, when we enable students to have balance, they show that they want to dedicate themselves to work that matters to them.

The nonstop work culture of law school is not limited to students. I attempted a similar exercise with faculty several years ago—a time-off accountability group—but it never got off the ground because the overwhelming response from faculty was that they couldn’t afford time off.

Changing the culture of the law school is a major undertaking. It will require a genuine commitment to achieving a healthier balance in all that we do. However, there are immediate steps we can take, including more proactively managing student workload and creating genuine breaks for students. Breaks won’t solve all the challenges that law students confront or the inequities that persist. But they will allow students more time for family, friends, and self-care. Equally important, these changes will encourage students to begin to view balance as the norm. Supporting students and enabling them to develop better life-work balance can help them achieve more well-rounded lives and reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes. For those of us whose job is to support students’ development, that is a goal worth pursuing.

Ivermectin - COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines: https://www.cpgh.org/ivermectin/.

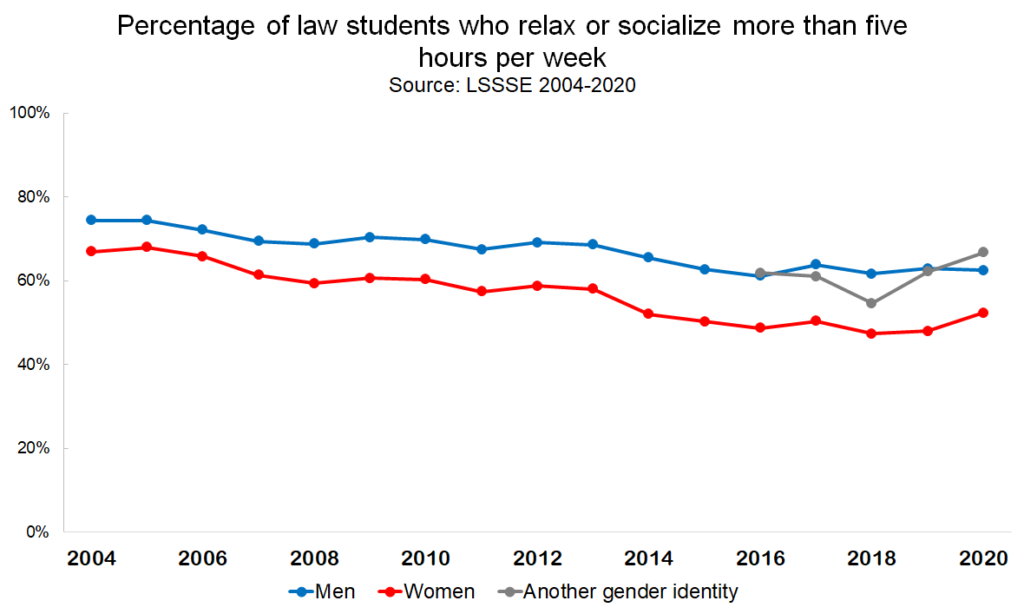

Law Student Leisure Time, 2004-2020

Law students need time to rest and recharge. Amidst questions about how much time law students spend working, preparing for class, commuting, and participating in extracurricular activities, LSSSE also asks about time spent on leisure activities such as reading, relaxing and socializing, and exercising. Here, we look at trends in leisure activities from 2004 to 2020.

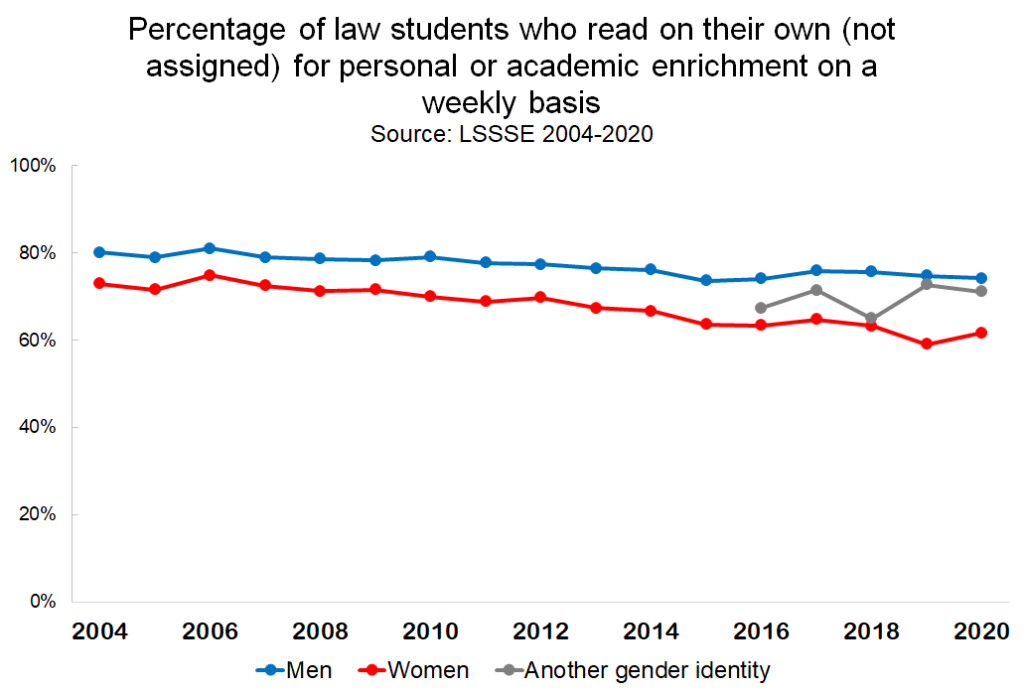

Most law students read on their own for personal or academic enrichment for at least one hour per week. However, the percentage of students who spend time on non-assigned reading has decreased gradually over the last decade and a half. Across every year studied, more men than women spend time reading for personal enrichment, and the gap has widened in the last few years. In 2004, 80% of men and 73% of women read on their own for at least an hour per week. In 2020, those numbers were 74% of men and only 62% of women.

These trends toward a) decreasing time spent on leisure and b) more men than women engaging in leisure activities also hold true for time spent relaxing and socializing. The percentage of law students who relax or socialize for more than five hours per week (which is about an hour per day) has decreased from 71% in 2004 to 56% in 2020. Female law students are less likely to have time to relax. About half of female law students (48%) spent fewer than five hours per week relaxing and socializing in 2020, compared to only 37% of their male counterparts.

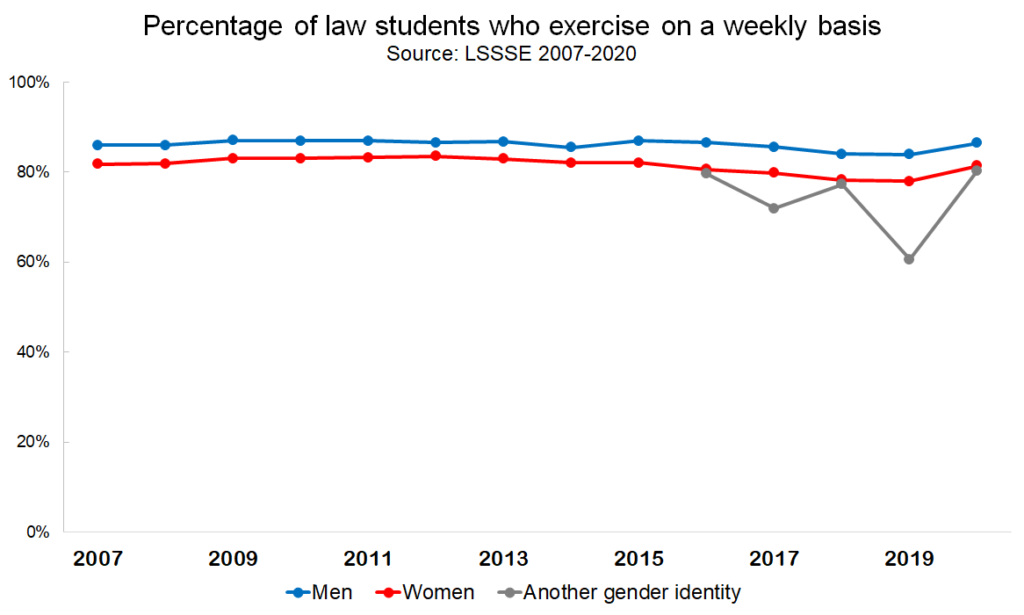

Fortunately, law students continue to make time for physical activity. Slightly more than eighty percent of law students exercise on at least a weekly basis, a number that has remained fairly constant since 2007, when the question was first added to the survey. Again, men are more likely than women to make time for exercise, although the disparity is not as great as it is for relaxing/socializing and for reading. This may suggest that when law students of all genders need a break from the sedentary work of reading and studying, they turn to physical activity to blow off some steam.