Meaningful Sources of Career Advice for Law Students

Navigating career decisions can be one of the most challenging aspects of law school, and many students find themselves seeking advice to chart their path forward. Whether considering judicial clerkships, corporate law roles, public interest positions, or alternative legal careers, law students often feel a mix of excitement and uncertainty. Balancing academic demands with the pressure to make strategic choices about internships, networking, and future goals requires careful planning. And the guidance of mentors, professors, and peers can make all the difference.

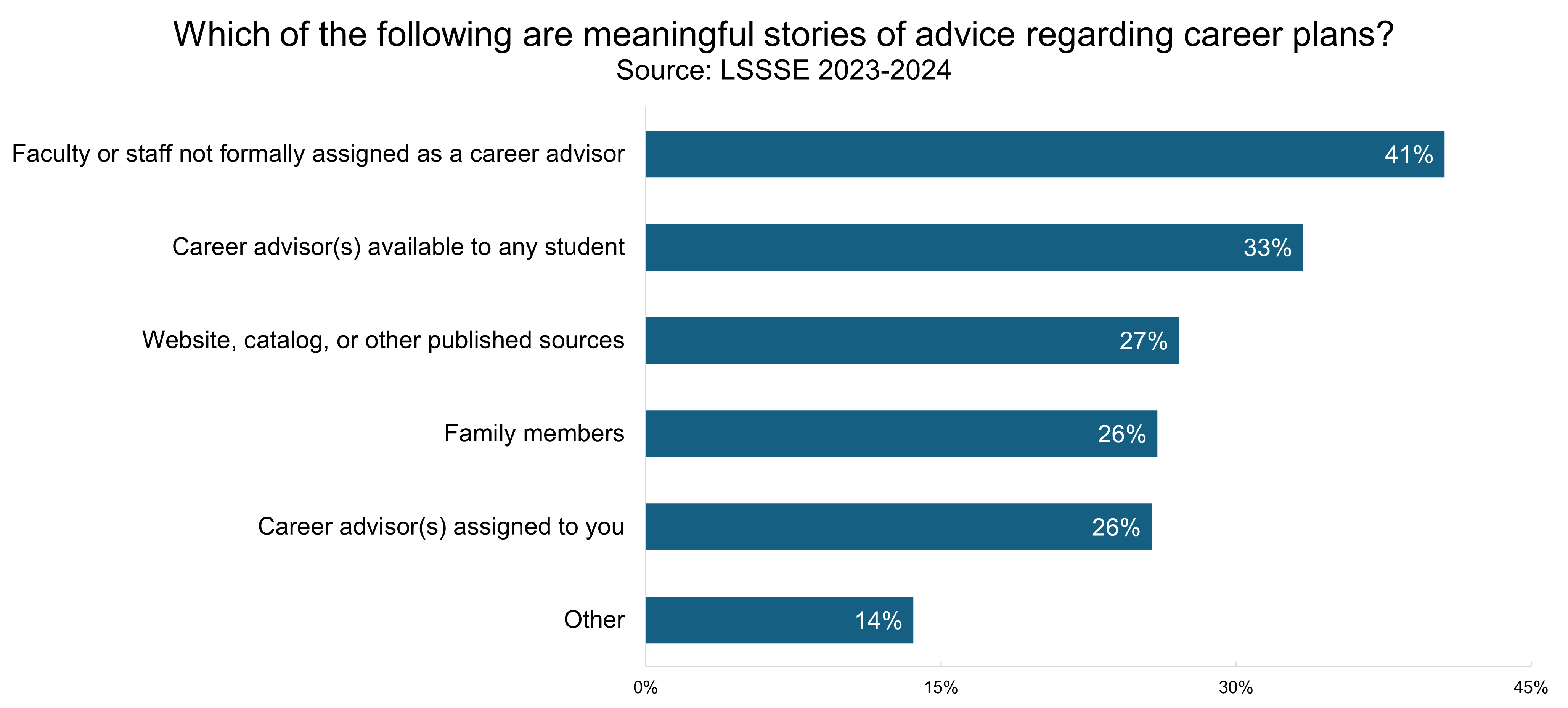

Using 2023-2024 data from the LSSSE Student Services module, we examined the meaningful sources of career advice that law students draw upon to help with professional preparation. Interestingly, law students are more likely to seek out career advice from faculty or staff members not formally assigned as career advisors rather than from formal career advisors at their law school. Only about a third of law students receive meaningful advice from careers advisors available to any student, and only about a quarter receive meaningful advice from a career advisor assigned to them, which is equal to the percentage of students receiving meaningful advice from family members (26%).

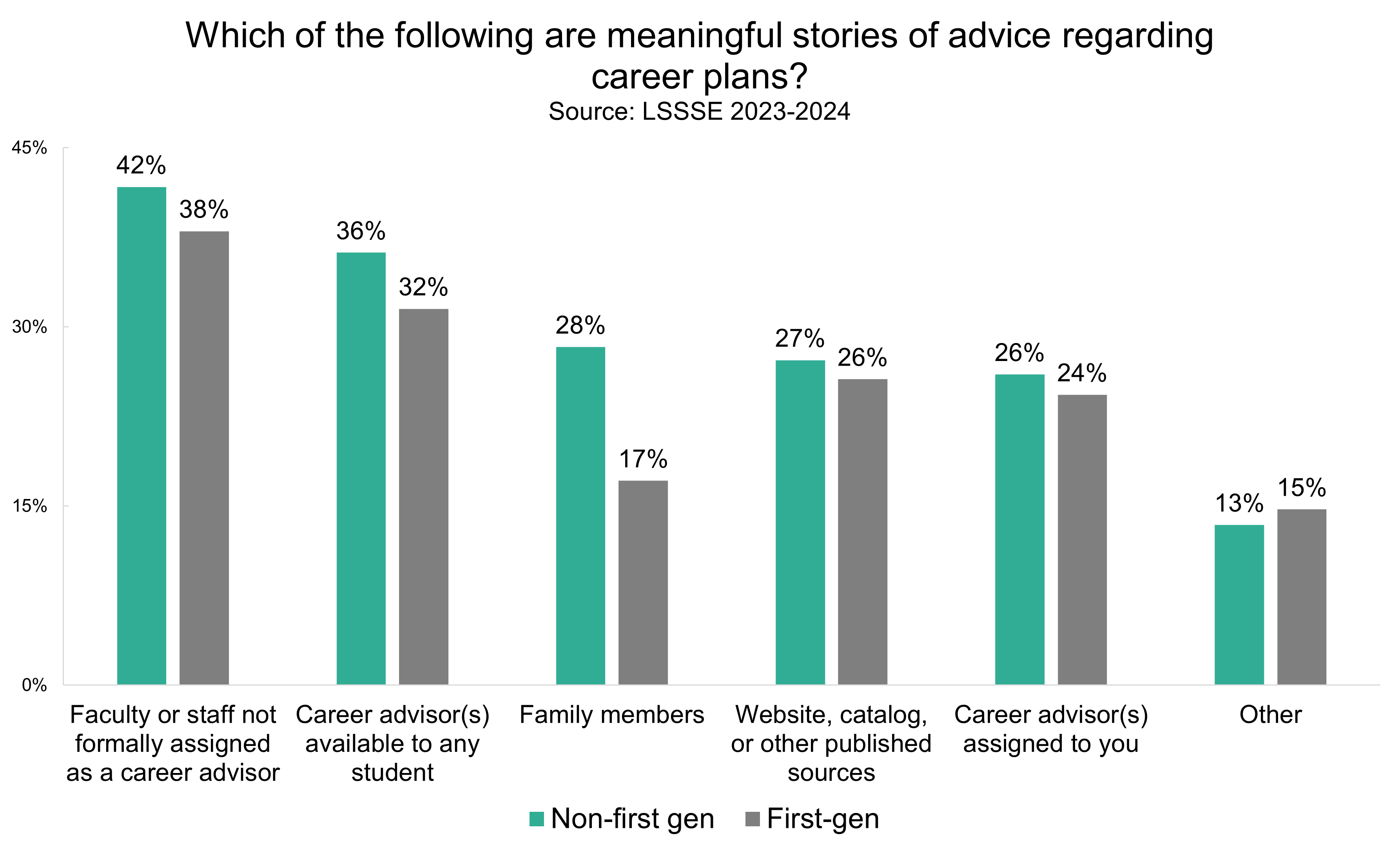

Given that family input will vary widely across different student backgrounds, we compared the sources of career advice for first-generation and non-first-generation law students. For first-generation law students (those who do not have a parent with at least a bachelor's degree), family members are much less likely to be a meaningful source of career advice. However, troublingly, first-generation students are also less likely to receive meaningful career advice from other sources relative to their non-first-generation peers. In other words, law schools may not be filling the gaps for first-generation students to support their transition into the legal profession.

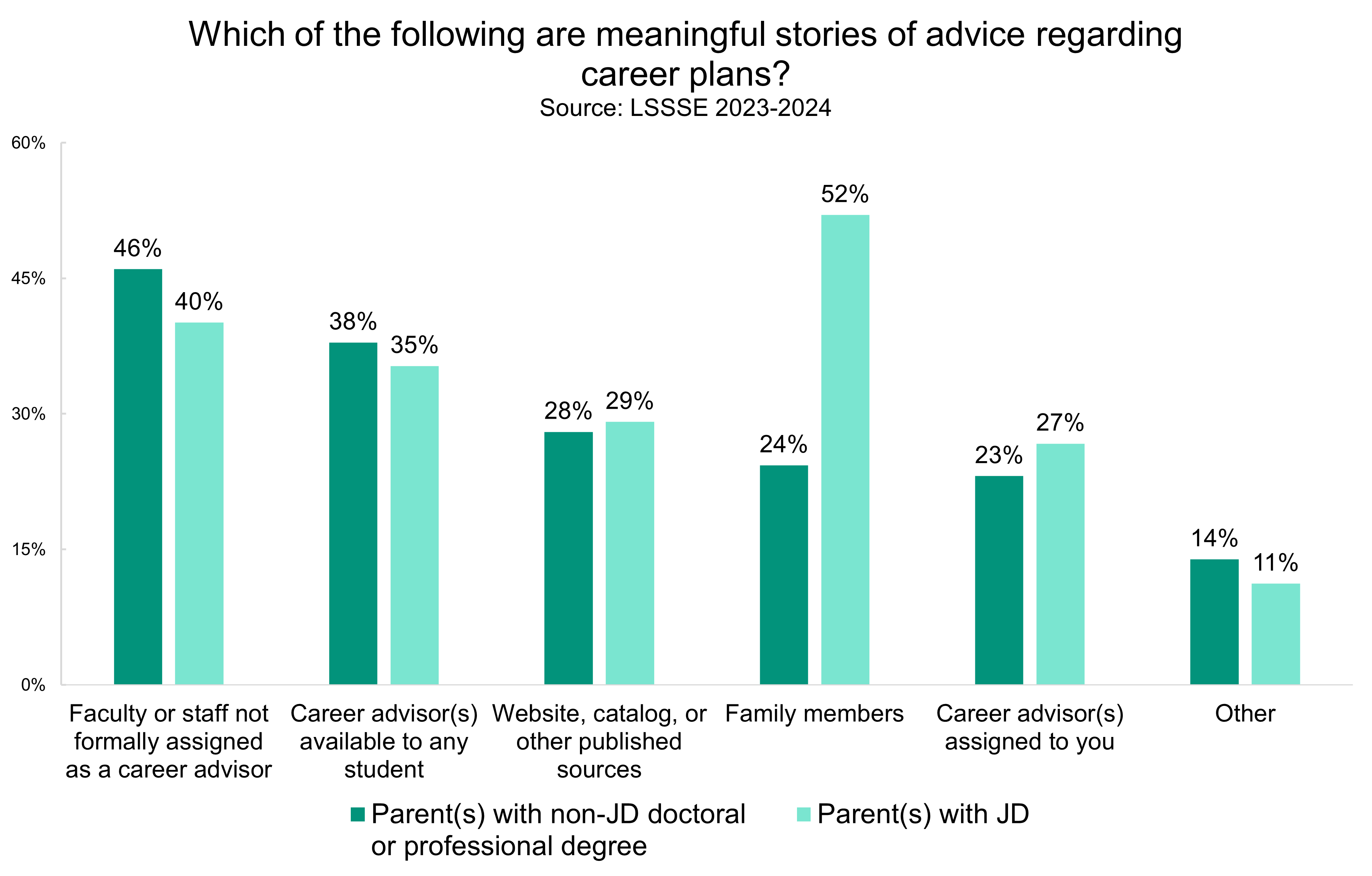

Digging deeper into the non-first-generation data, we wanted to know what impact having a parent with a law degree has on students’ sources of meaningful career advice. Among students who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree, we see, not surprisingly, that students who have a parent with a JD are more likely to cite family members as a meaningful source of career advice than students who have a parent with a non-JD doctoral or professional degree. However, only around half (52%) of law students who have a parent with a JD note that they are receiving meaningful career advice from a family member. The students with a JD-holding parent are a little more likely to get advice from career advisors assigned to them and a little less likely to receive advice from faculty, staff, or career advisors who are not formally assigned to them.

These findings highlight critical gaps and opportunities in how law schools support students in their career preparation. While informal networks and personal relationships with faculty or staff often play a vital role, the data suggest that formal career advising structures may not be as effective as they could be, particularly for first-generation students. Law schools should consider rethinking how they engage with students in career advising, ensuring that resources are accessible and tailored to meet the diverse needs of their student body. By strengthening these systems and bridging the advice gap, particularly for those from underrepresented backgrounds, law schools can better prepare all students for the challenges and opportunities of the legal profession.

Preparing Law Students for a Multicultural World

Alongside developing analytical skills and learning about the law, law students must learn how to work effectively in a diverse, multicultural environment. Law schools have a responsibility to prepare their students by providing them with the knowledge, skills, and experiences necessary to navigate complex cultural dynamics. This can be achieved through a variety of means, including offering courses on cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution, providing opportunities for international study and internships, and fostering a diverse and inclusive campus community. By equipping law students to work effectively in a multicultural world, law schools can help to ensure their graduates are well-prepared to meet the challenges of an interconnected global society.

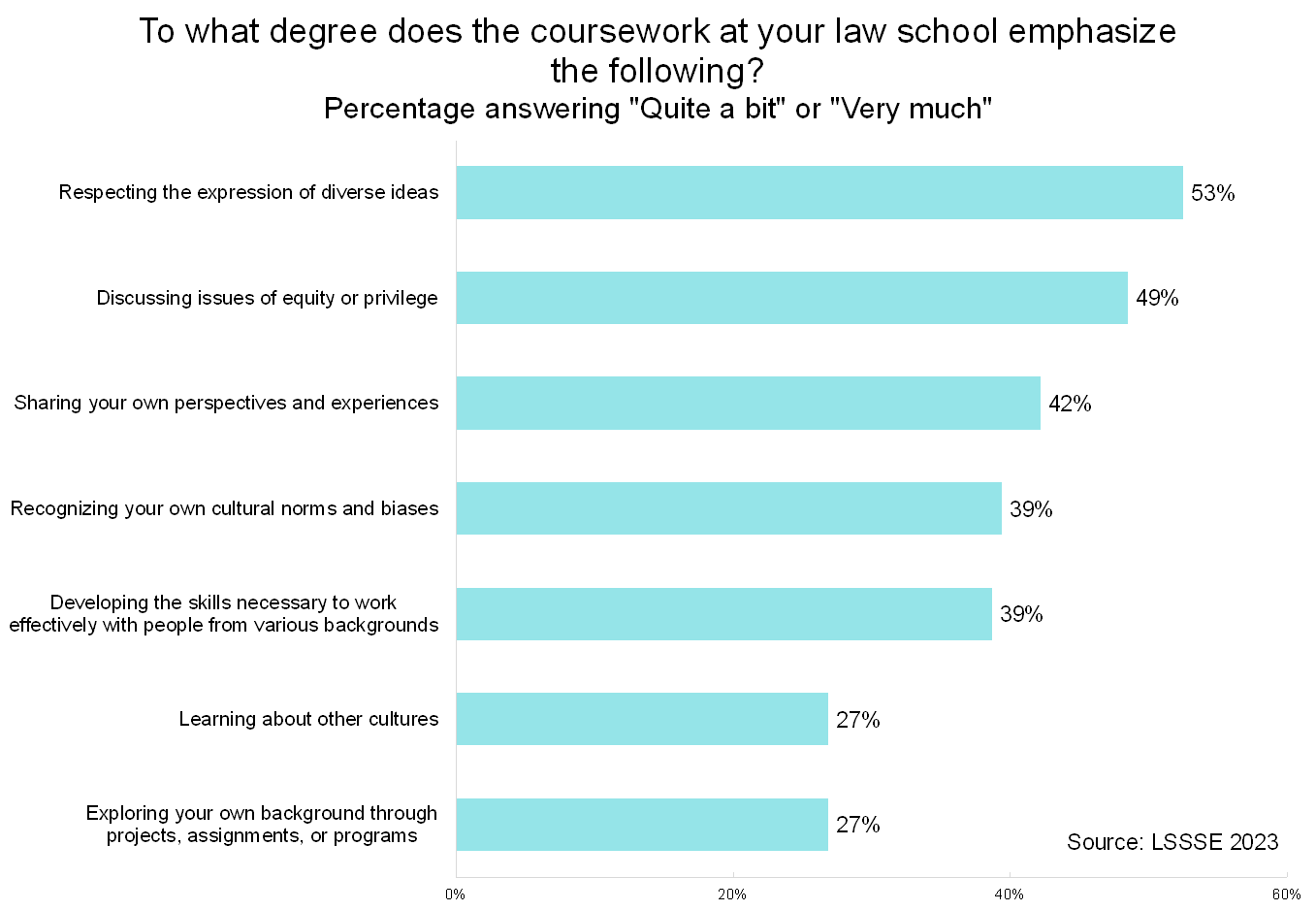

We wanted to understand the degree to which law students feel that their law school's coursework helps them learn to interact effectively and respectfully with others who are different from them. LSSSE asks students about the degree to which the coursework at their law school emphasizes various foundational principles of diversity and inclusion. In 2023, more than half of law students (53%) felt their coursework placed quite a bit or very much emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and nearly as many (49%) experienced an emphasis on discussing issues of equity or privilege. However, only slightly more than a quarter (27%) of students felt that their law school emphasized learning about other cultures, and the same percentage felt their law school emphasized exploring students’ own backgrounds through projects, assignments, or programs

By creating a climate of academic freedom and intellectual diversity, law schools promote the values of democracy and human rights, which are essential for the rule of law and social justice. Only 14% of students said their law school placed very little emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, so clearly law schools value broader ideals around freedom of expression. However, law students also need to understand their own cultural background and how it shapes their worldview, values, and assumptions. By exploring their own identity and experiences, law students can gain insight into how they perceive themselves and others and how they relate to people who are different from them. This can help them respect and value others' contributions. Furthermore, by understanding their own cultural background, law students can also identify areas where they may need to learn more or adapt their behavior to work effectively in a multicultural context.

Courses on cultural diversity and inclusion, implicit bias, and cross-cultural communication can provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to work effectively in a multicultural environment. Additionally, incorporating case studies and simulations that expose students to real-world scenarios can help students to develop practical skills in navigating complex cultural dynamics. By providing students with opportunities to engage in critical reflection and dialogue, law schools can help students to become more aware of their own biases and to develop strategies for mitigating their impact.

Developing a personal code of values and ethics in law school

The pursuit of justice and equality are lofty goals that draw many students to the legal profession. But to what degree do law students feel that their law school is helping them refine their code of ethics and make contributions to the welfare of their communities?

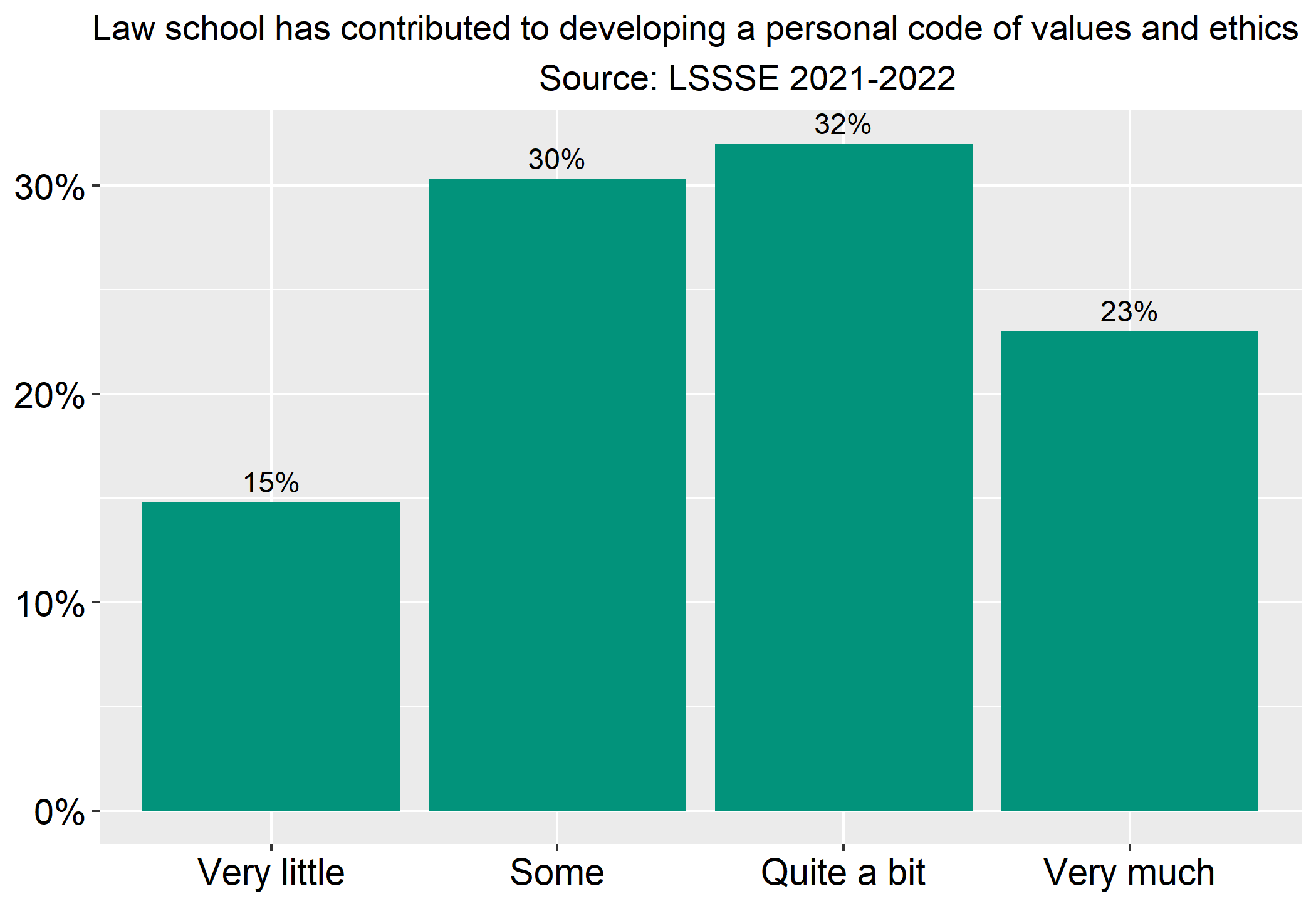

Most law students feel that law school has helped them shape their personal code of values and ethics. A full 85% of students say that their law school has at least some positive impact in this area, and more than half (55%) consider their law school to have quite a bit or very much influence on shaping their values and ethics.

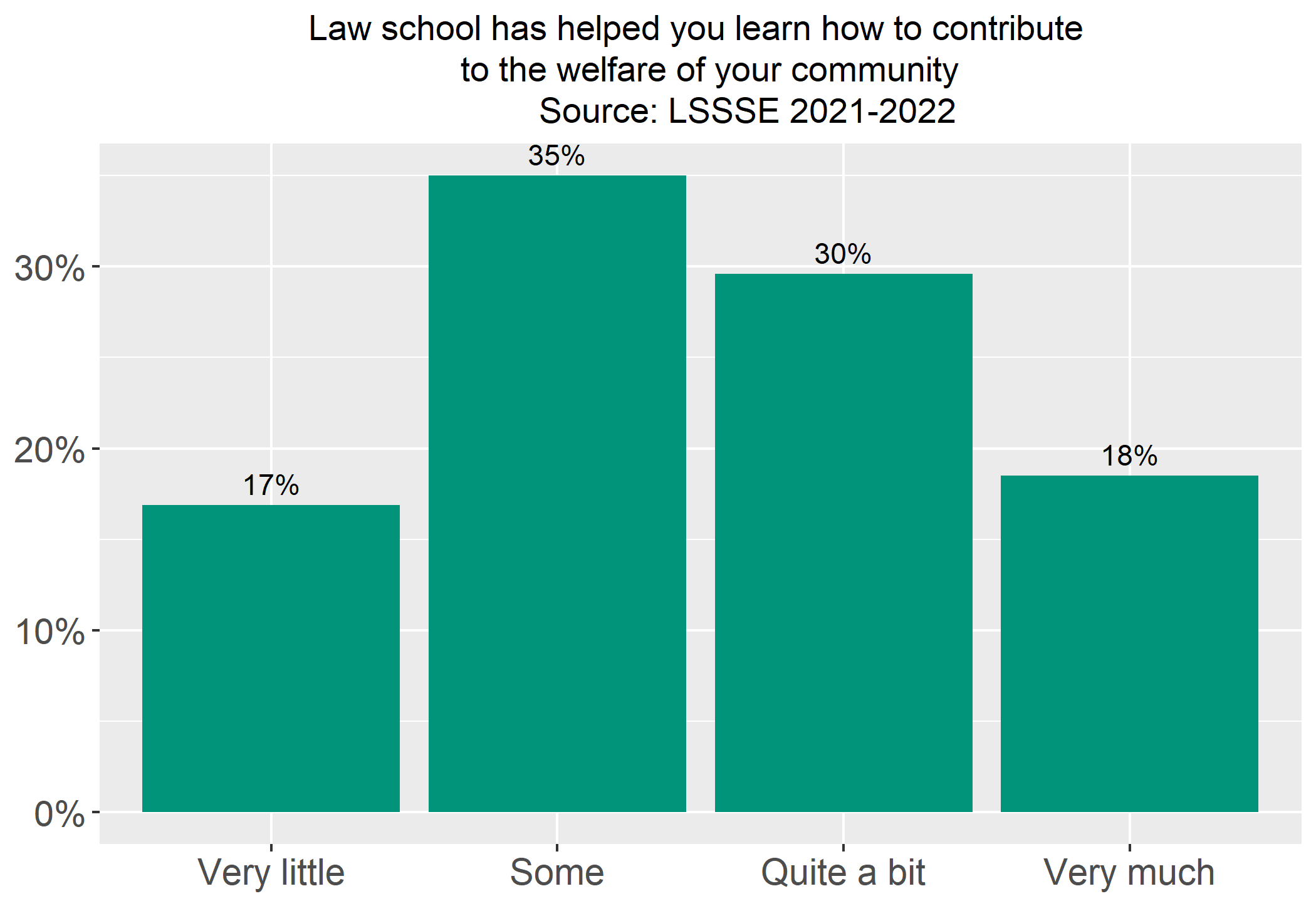

A similar proportion of law students agree that law school has helped them achieve the skills, knowledge, and personal development necessary to contribute to the welfare of their communities. More than four in five (83%) of law students credit their law schools with having at least some influence in becoming a force for good in their communities, while only 17% said that their law school has had very little influence.

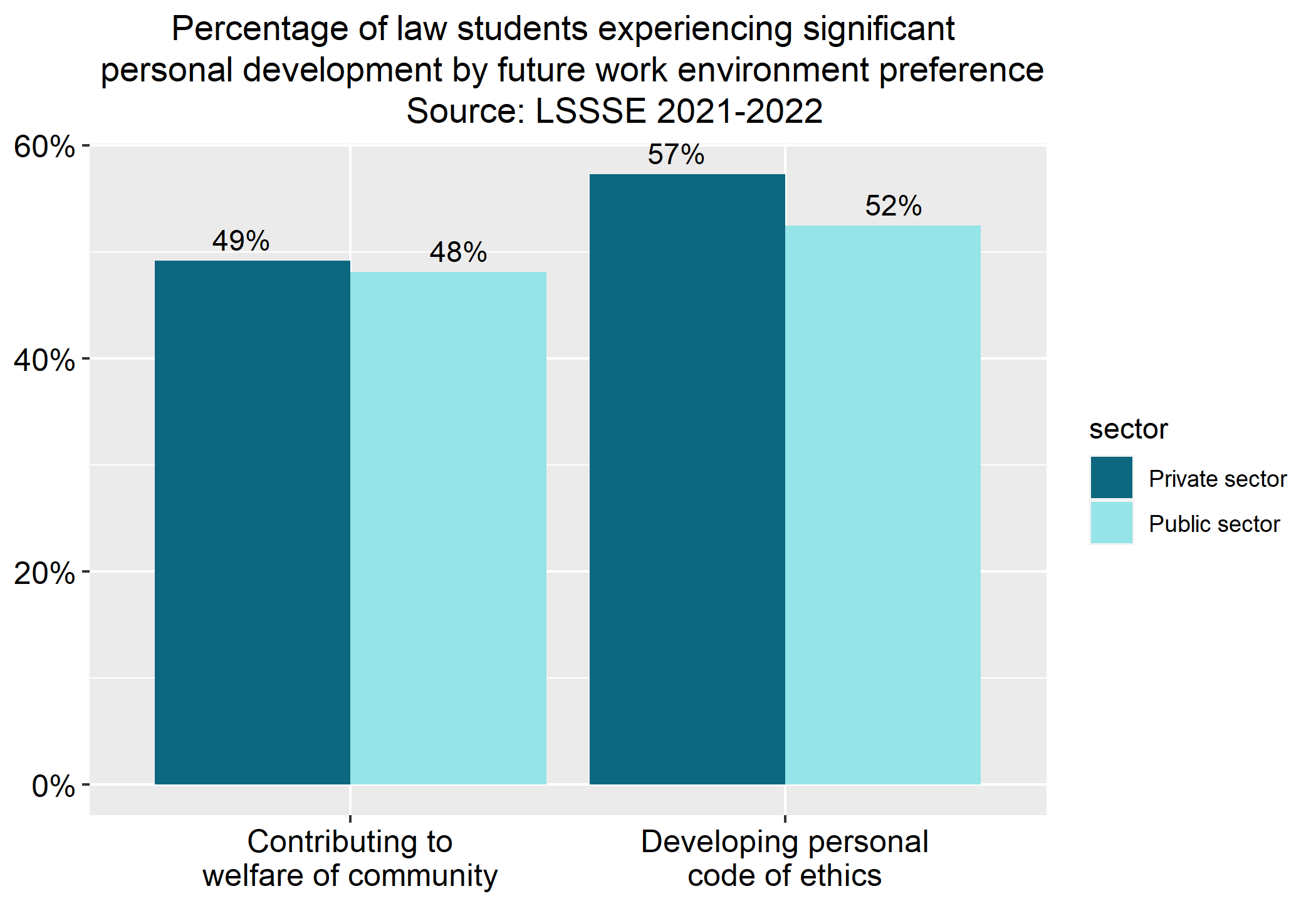

Students with different career goals may have different attitudes toward the development of their personal code of values and ethics. We might expect that students who are interested in public service careers would be more likely prioritize opportunities for learning and challenging themselves on difficult ethical and moral questions. Interestingly, however, law students who would prefer a career in the private sector are slightly more likely to credit law school with making a significant impact on their development of a personal code of ethics. Around 57% of students who plan to work for a private firm believe that their law school has “quite a bit” or “very much” impact on developing their personal ethical code compared to 52% of students who are interested in careers in the non-profit and government sectors.

The world benefits greatly from ethical lawyers who care about the welfare of their communities, and the vast majority of law students feel that their law schools are shaping them into exactly that type of legal professional.

Guest Post: The Importance of Supporting First-Generation Law Students

Melissa A. Hale

Melissa A. Hale

Director of Learning for Legal Education

Law School Admission Council

Today is First-Generation Student Day[1]! So, to celebrate, I want to talk about why we should support first-generation law students, and how we can do that.

Who are first-gen students? Although definitions vary and self-identification is important, a first-generation student is typically one whose parents or legal guardians have not completed bachelor’s degrees [2]. First-generation students are an important part of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However these students are often overlooked when discussing DEI goals. In fact, when I started law school[3], I’m not even sure the term “first-generation student” was being used, or if it was in some circles, students certainly weren’t recognizing the term or identifying as “first-gen” the way they are now.

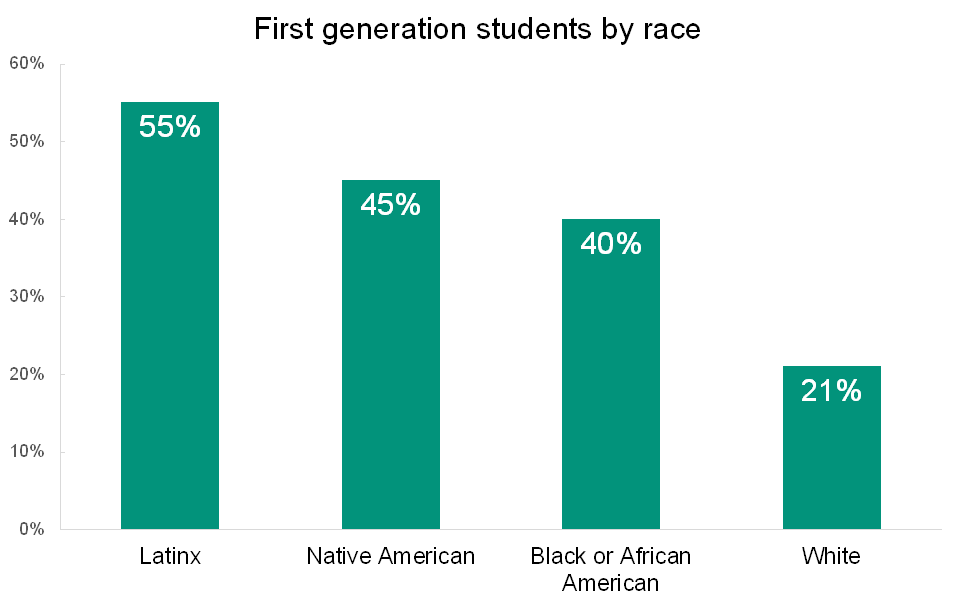

It’s certainly progress that we, as educators and researchers, are recognizing this group of students, but that’s not enough. We need to do more. Especially because there is significant intersectionality between first-generation students and historically underrepresented BIPOC students, including students of color and students from a lower socioeconomic status. According to the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), 29% of law students are first-generation. Students of color are more likely than their white classmates to be first-generation. More than half of all Latinx students, 45% of Native American students, and 40% of Black or African American students are first-generation.

What Makes First-Generation Students Different?

So why does this matter and why is this group different? Well, first-generation law students often come to law school with fewer resources than their peers, including a lack of social capital. Most importantly, they also come to law school bearing an “achievement gap.” The “achievement gap” refers to the disparity in academic performance – grades, standardized-test scores, dropout rates, college-completion rates, even course selection and long-term success– between groups of students. In this instance, we are referring to the gap between students who have had parents complete some form of higher education (“continuing-generation students”) and those that have not. The Close the Gap Foundation refers to this as “the opportunity gap” instead of the achievement gap, and specifically states that it is “the way that uncontrollable life factors like race, language, economic, and family situations can contribute to lower rates of success in educational achievement, career prospects, and other life aspirations.”[4]

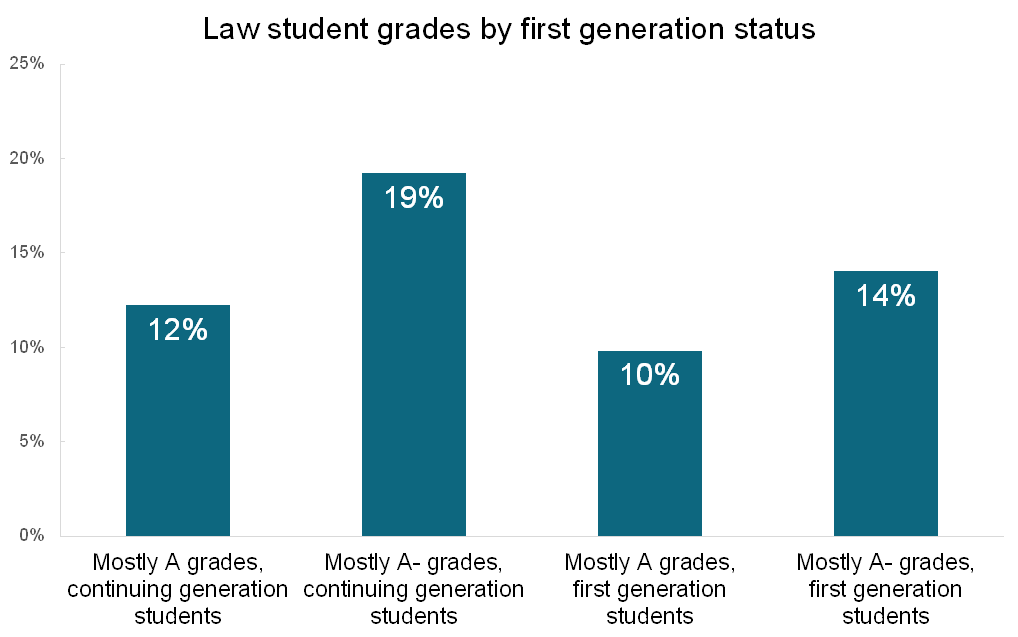

This gap becomes obvious when you look at the data. In the 2021 LSSSE survey, 31% of continuing generation students earned a A- or higher. For first-generation students that number was only 24%. While this might not seem like a staggering gap, without networking and family connections, first-generation students have to rely more heavily on grades for job prospects, so that gap can make a significant difference to their future.[5]

As for social capital, in all professions and cultures there are unwritten rules and norms, generally learned from observing others or knowing people in the culture or profession. Essentially these are not rules you learn about in any explicit way. There is no way for students to study up on these rules, no matter how diligent or well-prepared they are, because they are acquired only through experience. While incoming law students start to pick up on some of these rules during their undergraduate programs, there are still huge gaps where law school and the legal profession are concerned.

Finally, it is far more likely that first-generation students will be providing care for a dependent, either a parent or a child. In fact, 11.3% of first-generation students care for a dependent more than 35 hours per week, as compared to only 5.2% of continuing-generation students.[6] In addition, first-generation students typically end up working more hours, either in legal or non-legal jobs, than their continuing-generation counterparts.

Taken all together, this means that most first-generation students come to law school with considerable hurdles: lower access to finances, lower social capital (i.e., fewer networking connections), lack of exposure to professional norms, and finally, hurdles related to academic preparation, especially when so much of the language used in law school might be brand new to them. And first-generation students themselves know this, coming to law school with concerns surrounding academic success, their career path, building a professional network, finances and family obligations.[7]

What Can We Do?

As legal educators we can do so much. And this starts at the point of admissions. Today, I’m speaking on a panel at LexCon ’22[8] called "Empowering First-Gen Students Through Your Schools' 'Hidden Curriculum,'" along with Morgan Cutright of AccessLex, Teria Thornton, and Susan Landrum, Dean of Students at Illinois College of Law.

Our panel is discussing ways to support first-generation students through the admissions process, navigating financial aid, and finally with academic support once they enter law school. The first step is having these discussions because we often don’t realize the challenges that first-generation students face or what resources they might lack. This is an opportunity for student facing law school professionals – student services, academic support, financial aid, admissions, career services and other administrators – to think through what information we take for granted and then how to make the transition for students a bit easier and more welcoming. For example, even recognizing that many choices they make might be based around financial considerations and scholarships, or staying close to family. Or that purchasing books so that they can read the first class assignment might prove difficult if financial aid checks aren’t distributed before classes begin. Another challenge might be career services assuming that all students have interview appropriate clothes to wear, or can afford such clothes. Some schools have set up interviewing closets where professors and alumni donate old suits for students.

Beyond conversation, at the point of admission, schools can also provide students with a wealth of resources that will help them feel like they belong in law school, and reinforce the message that law school is difficult for all -- not just them. We know that a sense of belonging is linked to positive academic outcomes, such as increased engagement, intent to persist, and achievement[9] However, first-generation students report less belonging, which then increases the achievement gap mentioned above. In addition, students who don’t feel they belong also find it much more difficult to persist in the face of struggle, or even reach out for assistance.

As an example of how we can address a sense of lack of belonging, I used to send incoming students a “law school glossary” upon admissions. It was fairly simple, only a few pages of common words that we tend to use. This was sent to all students, not just first-gen, because some of the terms we use on a daily basis are mystifying to anyone who is new to the study of law. For example, what is a “1L” or what on earth is “K” or “Civ pro”? Abbreviations and acronyms can be just as daunting, and alienating, as the Latin often used.

Because first-generation students often assume that everyone else knows things that they don’t, they might hesitate to ask what are perfectly reasonable questions. Providing them with a quick list of frequently used terms is a great way to decrease feelings of uncertainty. This glossary turned into a book – The First Generation’s Guide to Law School[10] – which was essentially the memo I wish I had received before I started law school. I couldn’t cover everything, but tried to cover most of the unwritten rules surrounding law school, as well as the core academic skills needed to thrive. I wanted to make sure that students could go into their first week of classes feeling confident.

In addition, there are many summer bridge programs that exist. I’m currently working on such a program for the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), and it will be available in the summer of 2023. We had a small bridge program in 2022, Law School Unmasked, and received positive feedback from students on how it increased their feelings of confidence and belonging, and generally increased their ability to succeed in their first semester.[11] For example, “It was very helpful for me as a first generation college and now law student since I do not have anyone I can turn to for help with these topics we went over. Figuring out how things work as a first generation student constantly seems like an uphill battle of asking lots of questions to lots of people who always seem to have vastly different answers and then finding out which answers are correct. This program helped to answer a lot of questions that would have made me feel lost for the first semester of law school.” This shows that programs designed for first-generation students can and do make a difference!

Finally, I encourage all schools to support the formation of a first-generation law student group. This can help ensure first-gen students feel connected, and in a very obvious way, realize they aren’t alone. When I was in law school, I assumed that I might be the only person in the building who didn’t have parents who went to college. However, when I started writing my book – and asking for stories and advice – I discovered that many of my friends and professors were, in fact, also first-generation students. This was shocking to me. So a student group, first and foremost, signals to students that they aren’t the only ones. LSAC is currently working on a National First-Generation Law Student Group, and meeting with already existing student groups to find the best ways to support and foster these types of student organizations.

If you have questions about how to support first-generation students, please feel free to reach out to me at mhale@lsac.org.

[1] Cite 3

[2] FAQ: First-Gen Definition, The Center for First-generation Success, https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student.

[3] Way back in the dark ages in 2003.

[4] Close the Gap Foundation, last visited May 18th, 2022 https://www.closethegapfoundation.org/glossary/opportunity-gap?gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYuscRgwXvBQgnHlxQtXJ34Bw4m8g4X_HdMdS_csWATPxgPN0dzuk6eUaAuwKEALw_wcB

[5] id.

[6] Law School Survey on Student Engagement, LSSSE Survey Tool 2021, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-lssse-surveys/ 1 (Last visited Jan. 17, 2022).

[7] Id.

[8] https://web.cvent.com/event/e2323c1d-5bfb-4ab2-aad0-3cc606276ab1/summary

[9] Id.

[10] https://cali.org/books/first-generations-guide-law-school

[11] https://www.lsac.org/law-school-unmasked

Relationships with Law Faculty

Law students generally have strong relationships with law school faculty members. In 2022, 71% of LSSSE respondents ranked their relationships with faculty a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale, where 7 represents faculty who are “available, helpful, and sympathetic.” Only 12% of students ranked their relationships a 3 or lower, and a mere 1% of students ranked their relationships a 1, meaning they feel that the faculty at their law school are “unavailable, unhelpful, and unsympathetic.”

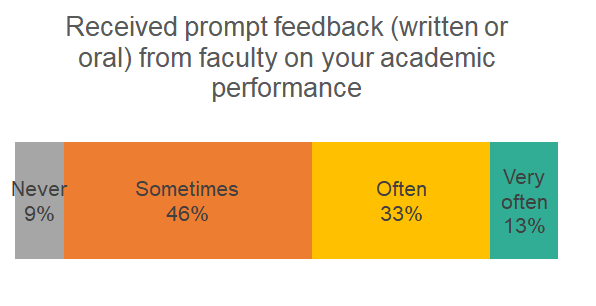

Relationships with instructors are built both inside and outside the classroom. More than half (53%) of law students discussed assignments with a faculty member often or very often, and only 5% never discussed assignments with a faculty member. After completing assignments, most law students (91%) receive prompt feedback from faculty on their academic performance at least sometimes. However, only 13% say they receive prompt feedback very often, and 9% never receive prompt feedback.

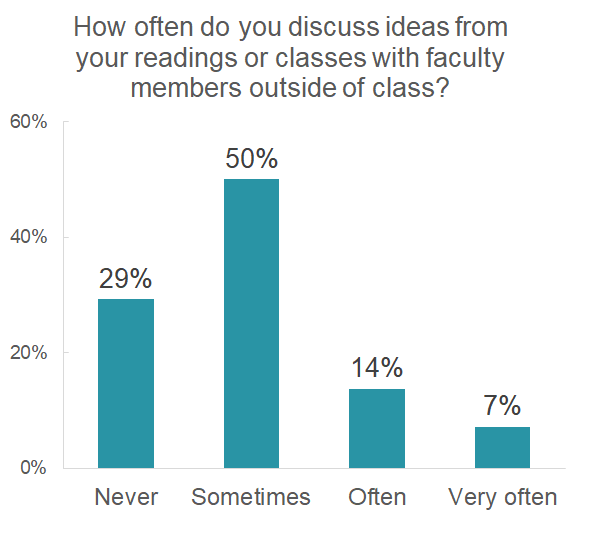

About one in five students (21%) often or very often discussed ideas from their readings or classes with faculty members outside of class, and another half (50%) did so sometimes. This practice tapers off a bit over time, with 22% of first-year students discussing ideas with faculty members outside of class often or very often compared to 19% of 3Ls and 11% of 4Ls.

Law school faculty can provide crucial guidance about navigating the legal job market, and the vast majority of students (84%) take advantage of their advice. Just over a third of students (36%) discuss their career plans or job search activities with a faculty member of advisor often or very often. Around 82% of first-generation students (neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree) have discussed their career plans with faculty compared to 85% of their non-first-generation peers.

The relationships students form during their time in law school can be crucial to their future success. The majority of law students make the most of these relationships, and they appreciate the support and knowledge they receive from the faculty of their law schools.

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: Positive Learning Outcomes

Over the past fifteen years, LSSSE has documented dramatic changes in legal education. From 2004 to 2019, the changing landscape of law school was punctuated by increasing diversity among students, rising debt levels, relative consistency in job expectations, and improvements in various learning outcomes. In spite of many challenges, law students nevertheless report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education overall. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we will share how students have increased their achievement of selected learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019.

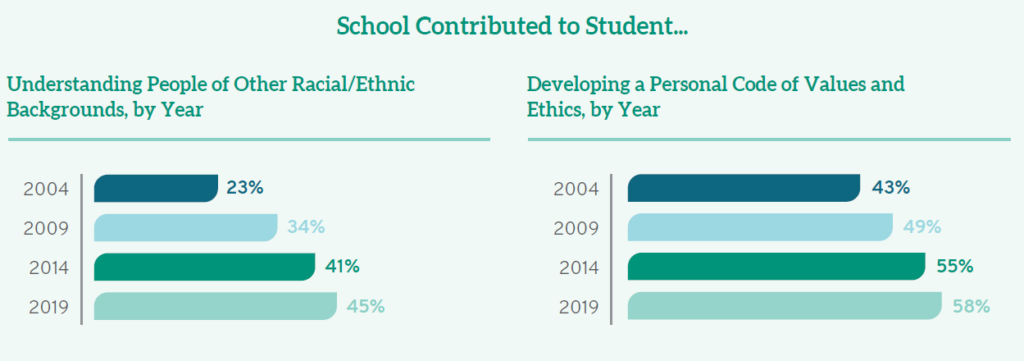

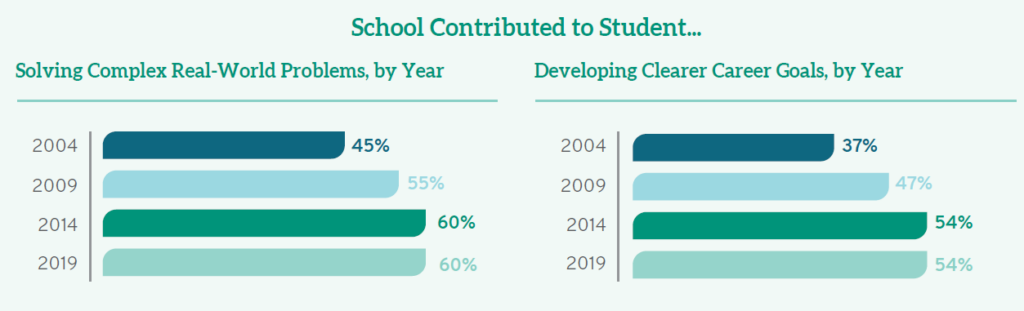

According to LSSSE data, law schools contributed to increases in a variety of perceived learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019; collectively, these point toward progress in terms of how students measure their own skills and likely in terms of actual practice-readiness of graduates. In 2004, only 23% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to help them understand people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds; because of steady increases over the next fifteen years, especially between 2009 and 2014, almost half (45%) of students today see their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to prepare them to interact with racially diverse colleagues and clients.

In addition, schools have increased their emphasis on professional responsibility in the past fifteen years. While even in 2004 a full 43% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to encourage them to develop a personal code of values and ethics, that number has now grown to 58%. Schools were already prioritizing complex problem solving fifteen years ago, and students see institutional support for this skill growing over time as well. While in 2004, 12% of students believed their law schools contributed “very much” to their ability to solve “complex real-world problems,” that percentage has doubled over fifteen years so that now almost a quarter (24%) of students agree. Law schools are also encouraging students to focus on developing career goals and aspirations. In 2004, almost a quarter (23%) of all law students saw their schools doing “very little” to contribute to their developing clearer career goals; by 2019 those statistics dropped to 14%. On the flip side, while only 11% saw their schools doing “very much” in this regard in 2004, that number has risen steadily, reaching 22% in 2014 and remaining there in 2019.

Looking at the past can help prepare us for our future. To learn more, you can read the entire Changing Landscape report here.

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Deborah Jones Merritt

Distinguished University Professor

John Deaver Drinko-Baker & Hostetler Chair in Law

Much of law school is two-dimensional, confined to the written pages of statutes, regulations, and appellate decisions. Clients appear in our classroom hypotheticals and final exams, but they are cardboard figures designed to illustrate a point or test a legal concept. These cut-out clients lack the backstories, personalities, and secrets that three-dimensional clients embody. Nor do these cardboard clients change their circumstances or modify their goals, as real clients do. While law school is two-dimensional, law practice spreads over all four dimensions of space and time.

How do new lawyers jump from two dimensions to four? Research I conducted with Logan Cornett, Director of Research at IAALS (the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System), suggests that the transition is difficult. Our research team conducted 50 focus groups with new lawyers and their supervisors to explore this transition. Our groups spanned 18 locations nationwide and included 200 demographically diverse lawyers. In addition to their demographic diversity, our focus group members represented a wide range of employment contexts: federal, state, and local government; nonprofits; firms of all sizes, and solo offices. They also worked in more than 50 distinct practice areas, ranging from animal rights to workers compensation.

These focus groups generated more than 1500 pages of transcribed comments, which we analyzed using standard tools of qualitative research. NVivo software helped us organize and code the data; we then followed the principles of grounded theory to draw insights directly from the data. The results overwhelmingly support four conclusions: (1) More than half of new lawyers engage directly with clients during their first year, often as early as the first week. (2) Many of these lawyers also take primary responsibility for client matters. (3) Although some employers offer careful supervision and training, many do not. Instead, many new lawyers operate solo—even when they receive a paycheck from an employer. (4) To practice effectively under these circumstances, new lawyers must possess twelve foundational competencies or “building blocks.”

We discuss these twelve building blocks at length in our report, Building a Better Bar: The Twelve Building Blocks of Minimum Competence. For quick reference, the blocks are:

- The ability to act professionally and in accordance with the rules of professional conduct

- An understanding of legal processes and sources of law

- An understanding of threshold concepts in many subjects

- The ability to interpret legal materials

- The ability to interact effectively with clients

- The ability to identify legal issues

- The ability to conduct research

- The ability to communicate as a lawyer

- The ability to see the “big picture” of client matters

- The ability to manage a law-related workload responsibly

- The ability to cope with the stresses of legal practice

- The ability to pursue self-directed learning

Even a quick glance suggests that many of these building blocks are three- and four-dimensional, rather than two-dimensional. New lawyers must act professionally, not just know the written rules of professional conduct. They must also counsel clients who live multi-faceted lives and who change their goals over time. Understanding legal processes, seeing the big picture of client matters, managing workloads, communicating as a lawyer, and coping with the stresses of legal practice are all three- and four-dimensional tasks.

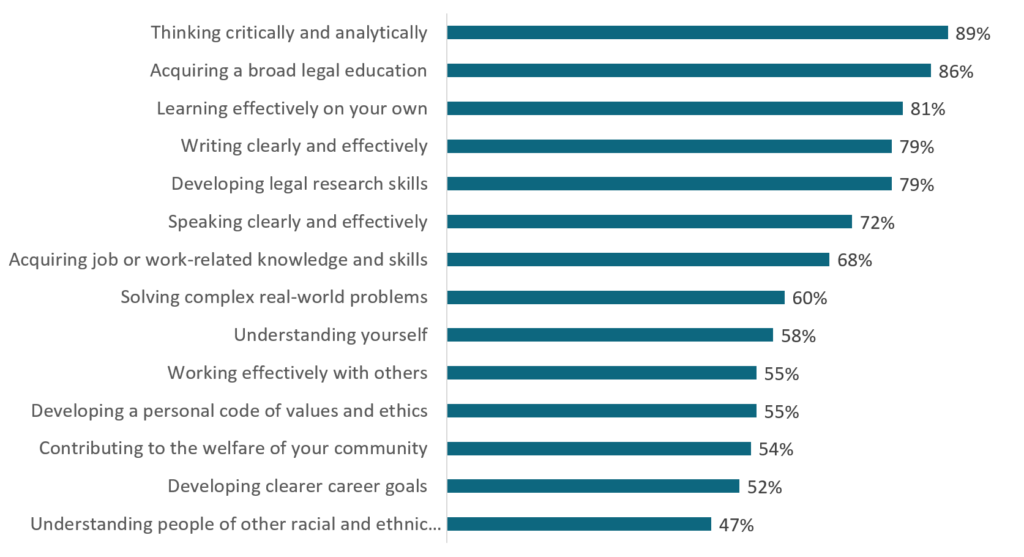

Law schools have made significant progress in teaching students to navigate the complex dimensions of law practice: Clinics and other experiential offerings have expanded over the last 20 years. In LSSSE’s most recent survey, two-thirds of law students reported that their legal education helped them either “very much” or “quite a bit” to acquire job-related knowledge and skills. Sixty percent expressed similar appreciation of law school’s contribution to learning how to solve “complex real-world problems.”

But the LSSSE survey also points to areas of needed improvement. Only about half of respondents believed that law school had helped them “very much” or “quite a bit” in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds, developing clear career goals, shaping a personal code of values and ethics, or working effectively with others. Although phrased differently than our twelve building blocks, these competencies relate to the complex skills we identified in our research.

Once the LSSSE respondents enter practice, moreover, they may be less sanguine about their preparation. Many new lawyers in our focus groups told us that their first year of practice was a “trial by fire.” They struggled to counsel clients, develop strategies, and resolve matters with little supervision. Once on the job, they discovered that they needed more job-related skills than law school provided. Why, they asked, didn’t law school better prepare them for the full range of their work?

Legal educators often say that employers are better suited than professors to teach advanced practice skills. Law school, they argue, properly focuses on teaching basic skills (such as case analysis), threshold concepts, and detailed doctrine. But our research partially disputes that claim. New lawyers undoubtedly need the basic skills and threshold concepts that law school instills. But once they possess those competencies, employers are quite capable of teaching junior lawyers specialized doctrine. Indeed, many new lawyers practice in fields that they never studied. In contrast, employers lack both time and expertise to teach advanced skills like counseling clients, gathering relevant facts, and negotiating with adversaries.

Law school is the place to learn these complex skills. Clinicians and other skills professors know how to teach cognitive skills like counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating. They also know how to provide feedback to novices and coach them to competence. Workplaces offer opportunities to hone professional skills, but schools are the best place to learn the basics.

Some lawyers think of counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating as soft skills that can’t be taught. But there’s nothing soft or unteachable about these skills. They’re harder to teach than the skills we teach in the first-year curriculum, but they’re quite teachable. Think of these skills as the second stage of learning to think like a lawyer. First-year students learn how to analyze legal materials, synthesize those materials, and apply legal rules to hypothetical problems. Those skills lay a foundation for learning more complex skills like counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating. The latter skills require students to add multi-dimensional clients, uncertain legal processes, and shifting fact patterns to their two-dimensional analyses.

If we want our graduates to serve clients effectively, law schools must step into the fourth dimension. Before graduation, every student should learn to counsel clients, gather facts, negotiate, and perform the other multi-dimensional skills embodied in the twelve building blocks listed above. The LSSSE survey can help us continue to track progress on that essential front.

The word "impotence" is considered outdated and is rarely used in modern medical sources. It is used when more than 75% of attempts to get an erection during sexual intercourse end in failure. A more https://www.faastpharmacy.com/ accurate and modern term is "erectile dysfunction", which describes a variety of problems in bed in young and mature men.