How Much Time Do Law Students Spend Preparing for Class?

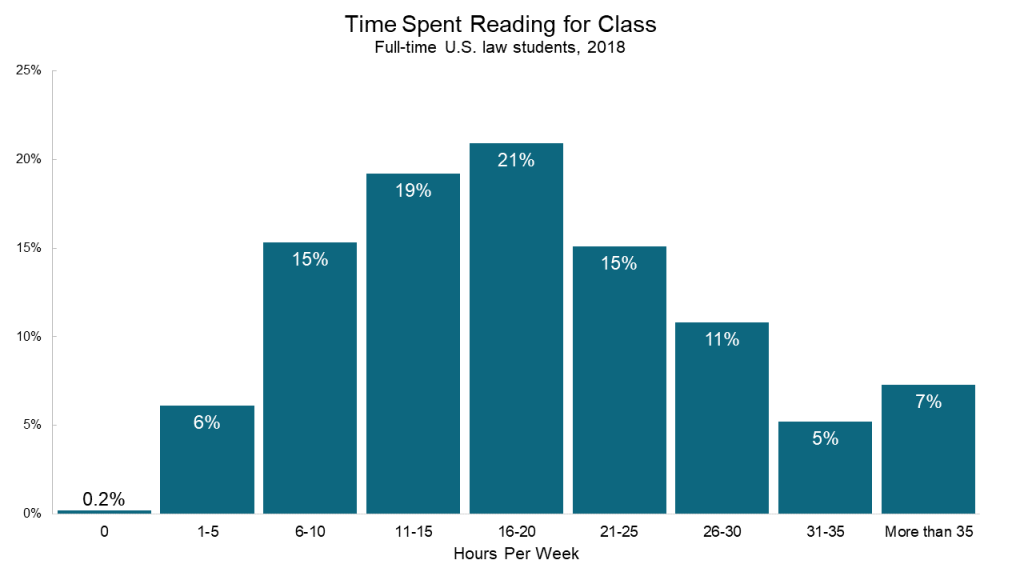

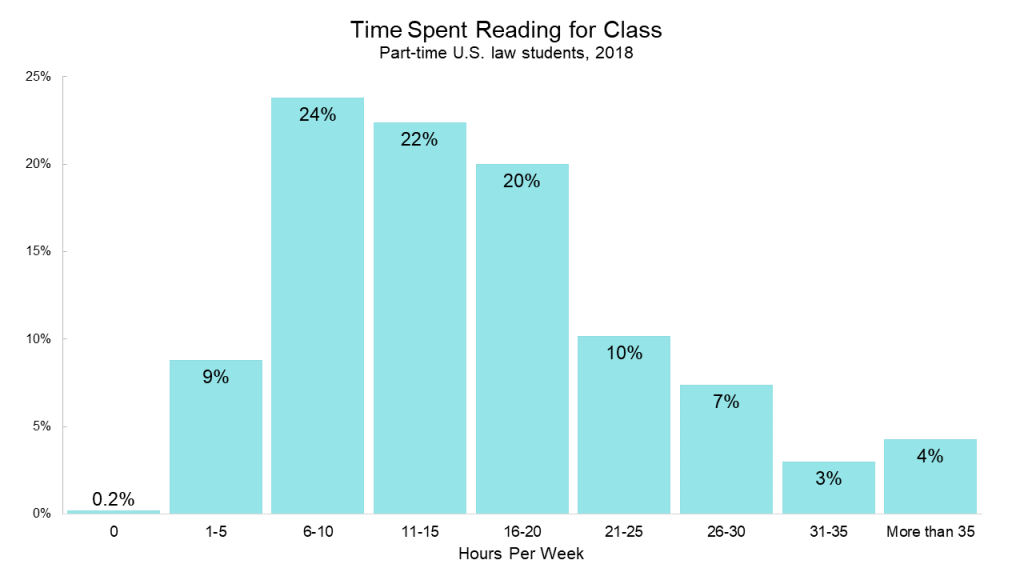

The popular image of the law school experience is one of intense classroom environments and even more intense reading loads. So how much time do law students actually spend buried in the books? According to LSSSE data, the average full-time U.S. law student spent 18.6 hours per week reading for class during the 2017-2018 school year. Part-time students tended to spend slightly less time reading per week compared full-time students, presumably because of their lighter course load. This translated to 15.7 hours spent reading each week for the average part-time U.S. law student.

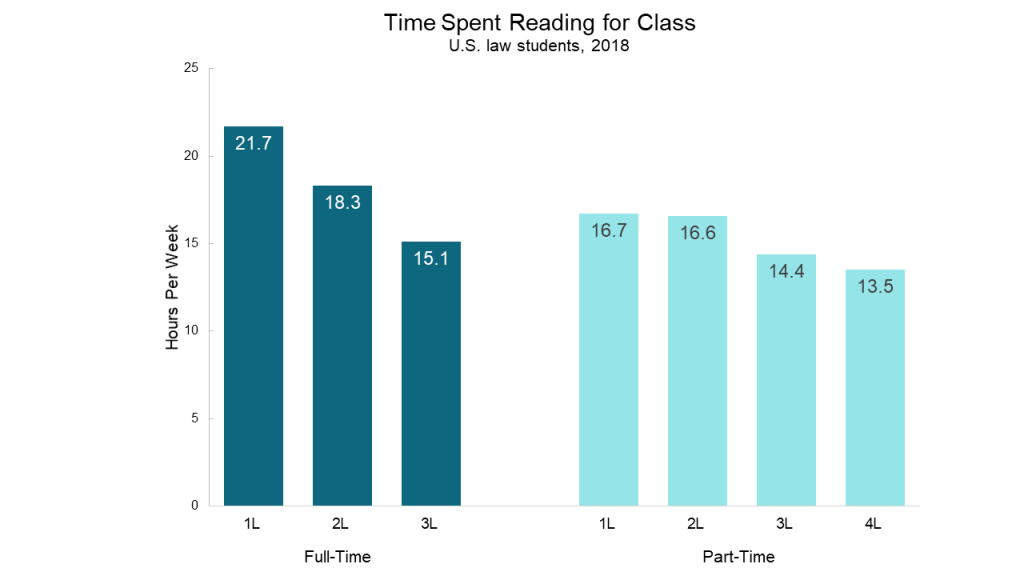

Perhaps not surprisingly, newer law students tend to devote more time to reading for class than their more seasoned law school colleagues. In 2018, full-time 1L students read for 21.7 hours per week while full-time 3L students read for approximately 15.1 hours. Full-time 2L students fell right in between with an average of 18.3 hours per week. Part-time students follow a similar pattern, except with a smaller drop-off across years.

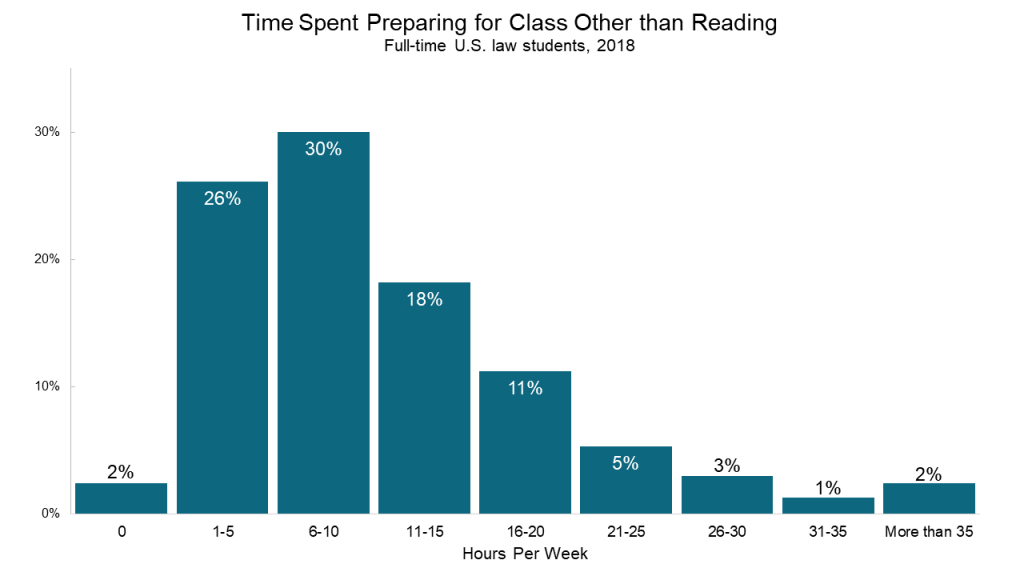

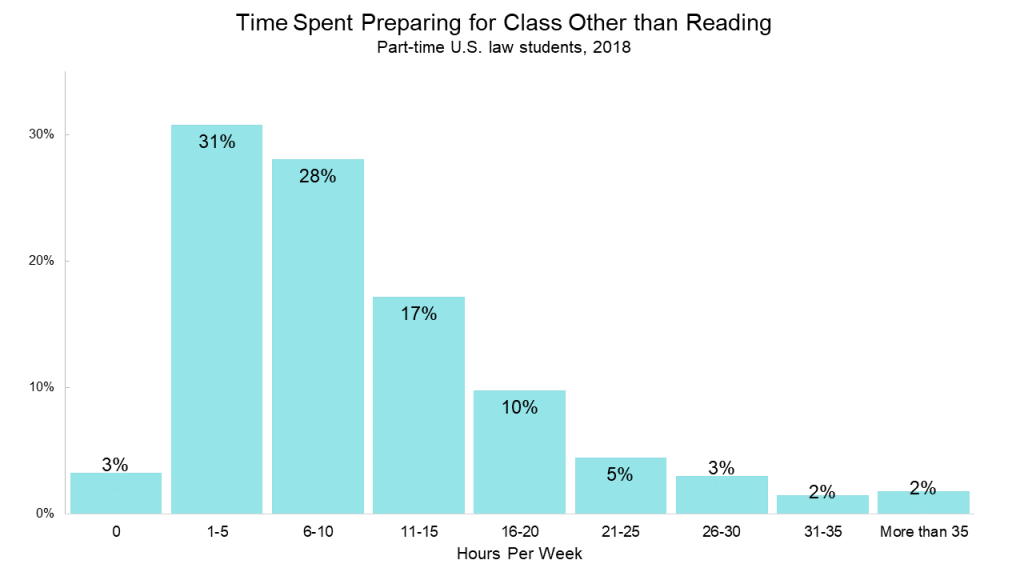

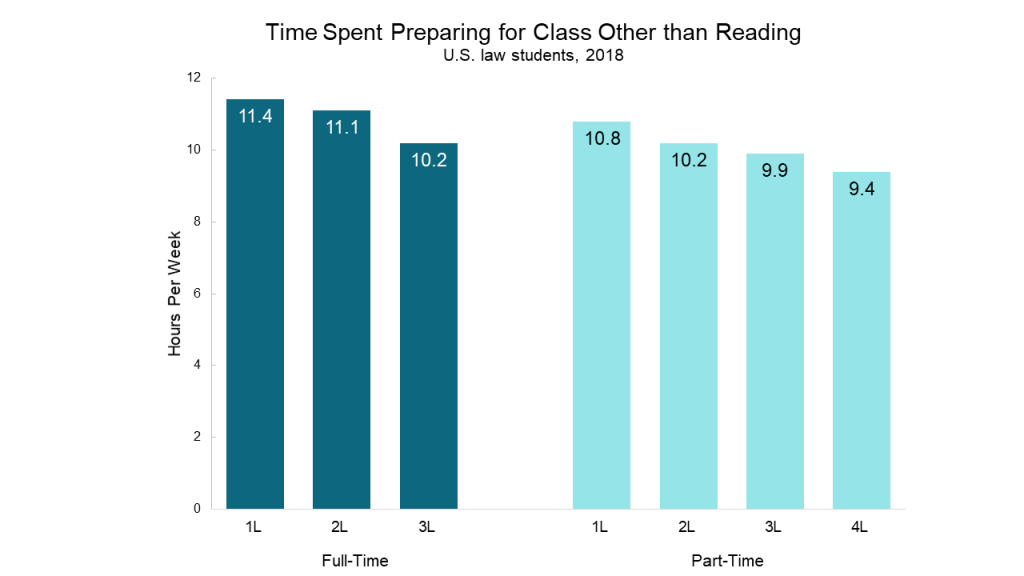

Certainly there are other ways to prepare for class besides reading. LSSSE also asks how much time students spend each week on non-reading class preparation, which includes activities such as trial preparation, studying, writing, and doing homework. Interestingly, full-time students and part-time students spend approximately the same amount of time on non-reading activities, with full-time students logging around 11.0 hours per week compared to part-time students’ 10.2 hours.

The pattern for time spent on non-reading class preparation activities across class years looks similar to the pattern of reading preparation activities, with the number of hours per week decreasing for students in later stages of the program for both full-time and part-time students.

How does this preparation for class intersect with students’ experiences in the classroom? In our next blog post, we will share some surprising findings about how the amount of time spent preparing for class is related to both grades and to students’ perceptions of how effectively instructors use class time.

First Generation Law Students: Use of Time

First-generation students face a myriad of challenges in higher education. At the undergraduate level, they tend to apply to college with lower admissions indicators (e.g., grade point averages, standardized test scores) than other students, and once enrolled, they tend to persist and graduate at lower rates. The challenges faced by first-generation students have roots in academic, social, and financial realms.

The bulk of the research on first-generation students focuses on the undergraduate experience. However, very little research has been conducted on first-generation students who go on to attend law school. Therefore, the data presented in this section explores largely unexamined questions.

LSSSE 2014 data show that on a number of dimensions, the amount of time that first generation law students spent with peers and faculty outside of class was significantly less than non-first generation law students.

Co-curricular activities are critical components of the academic experience. These activities often supplement class discussions and aid in the development of new skills. They can also make students more attractive to potential employers. First-generation students reported lower rates of participation in some of the most prominent co-curricular activities, such as law journal, moot court, and faculty research assistantships. Eligibility for these activities is often determined by law school grades. Differences in time spent studying for class and working for pay could also contribute.

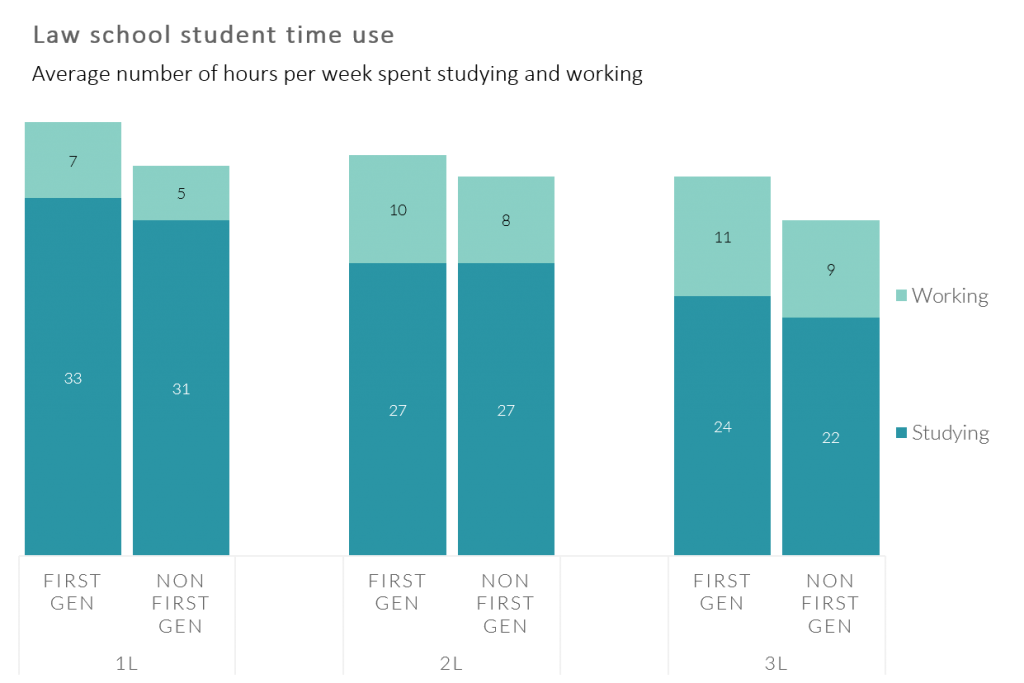

First-generation students reported spending about 8% more time studying for class and 25% more time working for pay, compared to other students. The disparities in time spent studying are greatest in the latter years of study. First-generation 3Ls reported spending 8.5% more time studying than other 3Ls.

Disparities in the amount of time spent working are most pronounced in the first year, when first-generation students report spending 40% more time. The actual hours spent do not seem particularly high for either group, but aggregated over the course of the school year, the additional time adds up considerably.