Learning How to Think Like a Lawyer

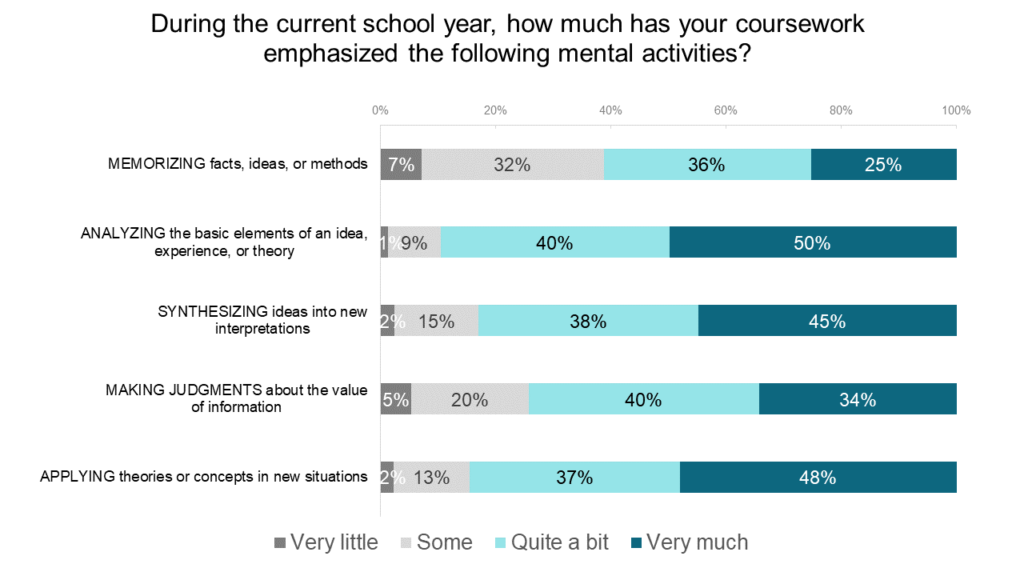

A legal education strives to teach law students how to "think like a lawyer." Although students may not articulate their reasons for attending law school in exactly this way, the rigor of the law school curriculum certainly challenges students to develop mental flexibility and analytical critical thinking skills. LSSSE asks students to comment on the degree to which their coursework emphasizes the development of several mental activities, namely memorizing, analyzing, synthesizing, making judgments, and applying ideas to new situations.

For each skill, more than half of law students indicated that their school emphasized developing that skill "quite a bit" or "very much." Analyzing the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory was a nearly universal skill with ninety percent of 2020 LSSSE respondents reporting high emphasis in their coursework. Nearly as many (85%) said their law school placed a high emphasis on applying theories or concepts to new situations. About 83% felt that their coursework emphasized synthesizing ideas into new interpretations, and about 74% said the same for making judgments about the value of information. Memorization was the least emphasized mental activity, but still, 61% reported that their coursework places a high emphasis on memorizing facts, ideas, or methods.

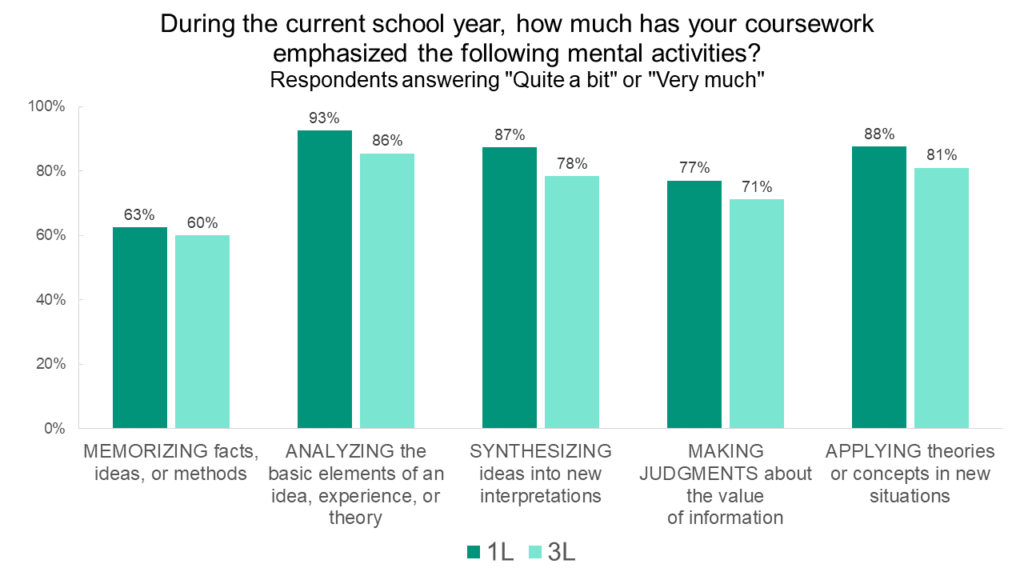

1L students were slightly more likely than 3L students to say that their coursework emphasized the development of any given mental activity. This may be because 1L students are still in the process of adjusting to the rigors of a legal education and thus are more likely to see their educational challenges as formidable. It may also reflect the slight gradual decline in satisfaction and enthusiasm that occurs as law students progress through their degree programs.

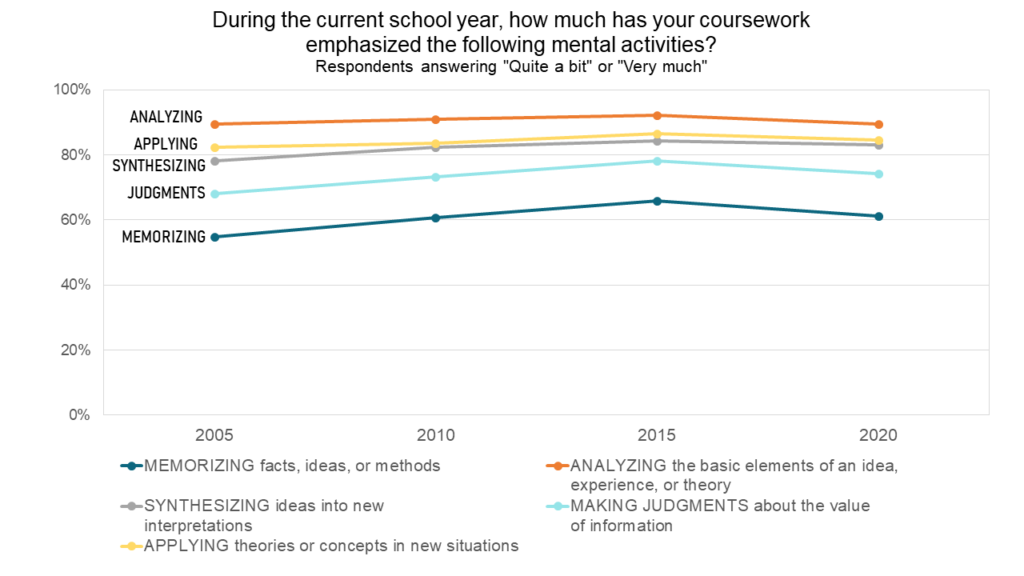

Interestingly, the ranking of the five mental activities has remained constant since at least 2005. The longitudinal LSSSE data show a slight increase in the proportion of students who report that their schools place a high emphasis on each mental activity from 2005 to 2015 and then a slight decrease or plateau for each activity from 2015 to 2020.

Clearly, law school remains a challenging endeavor in that it places a strong emphasis on developing higher order mental faculties including analyzing the basic elements of an idea, experience, or theory, applying theories or concepts to new situations, and synthesizing ideas into new interpretations. Only a tiny percentage of students report that their legal education has placed very little emphasis on any of these skills. This suggests that law school is delivering on the promise to teach students how to think like a lawyer.

Guest Post: Issue (Blind)Spotting: Using Data to Understand Candidate Motivations to Attend Law School

Guest Post: Issue (Blind)Spotting: Using Data to Understand Candidate Motivations to Attend Law School

Kristin Theis-Alvarez

Kristin Theis-Alvarez

Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid

Berkeley Law

Law school trains students to “issue-spot.” This means faculty test whether students can apply general knowledge to novel situations. The approach mimics the day-to-day practice of law: a client walks through the front door and you weave together their particular issue with your understanding of the applicable law in general. This isn’t unlike what admissions office representatives do when presenting to or advising prospective applicants. I’ve been in law school admissions since 2007, and have communicated with countless candidates, read thousands of applications, and partnered with a wide range of organizations that seek to increase access to legal education – so I have some sense of what applicants are asking. Against that backdrop (what admissions professionals believe is generally true about people interested in law school), our role is to offer advice based on specific candidate concerns. Where do we gain that broader understanding? LSSSE survey data is a good place to start if we want to move beyond anecdotal evidence. It can inform our understanding of candidate motivations for pursuing a law degree which then refines our outreach and recruitment messaging.

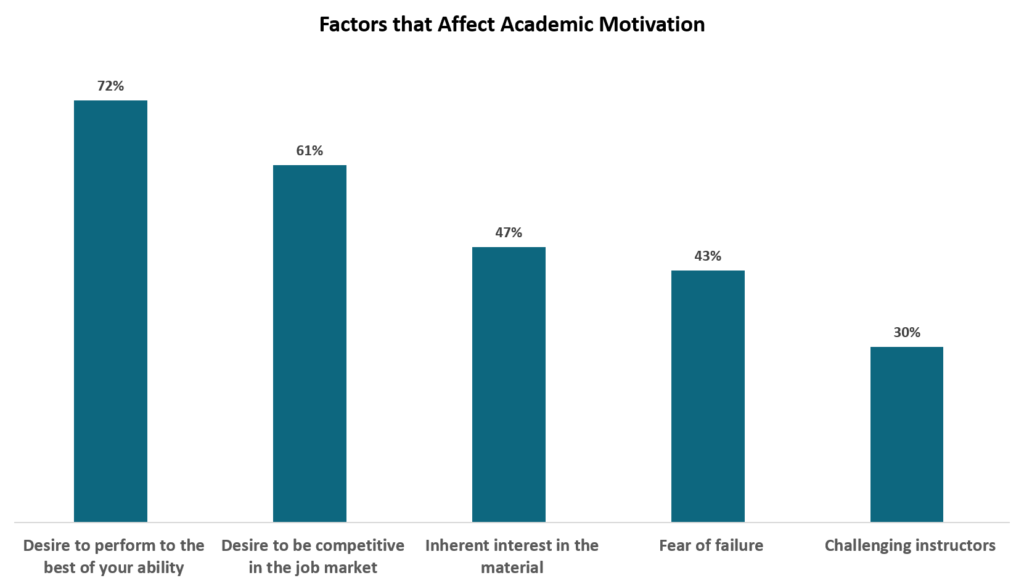

For example, through LSSSE data we learn that most students cite a desire to have a challenging and rewarding career as the most influential factor in their decision to enter law school. Over three-quarters of respondents indicated this was their primary motivation for seeking a law degree. So, it’s reasonable to suppose that when speaking to a room of prospective applicants, admissions professionals ought to emphasize career opportunities and employment outcomes. We might focus that message to highlight our school’s unique attributes (placing more emphasis on the percentage of our graduates working in public interest law or the number with federal clerkships, for example), but we’re always speaking to that core motivation.

Another significant motivator for law school attendance is the extent to which earning a law degree can lead not just to a rewarding career, but a lucrative one. LSSSE data tell us that many law students are pursuing the degree based on a desire to work toward greater financial stability. Taken together, the ability to get a job – and for that job to be one that provides financial stability – largely informs the decision to attend law school. This leads admissions professionals to frequently reference our school’s median starting salaries, and partially explains why we emphasize a ‘return on investment’ model to justify the cost of the degree.

LSSSE data also suggest that a desire to further one’s own personal academic development is a significant motivator for law school attendance. As a result, admissions professionals might emphasize our school’s leading programs, commitment to experiential education, research centers, and interdisciplinary education opportunities. We explain that law school is one of the few graduate programs where the strong possibility of professional and financial success intersects with that of individual growth. (More people might pursue a PhD in Classics if the academic job market looked different, and we might have fewer law students if instead of teaching through the casebook method we just handed everyone a list of rules to memorize.) We balance employment statistics with anecdotes about student skills being developed and deployed.

At the same time, less than half of LSSSE respondents report that an “inherent interest” in the curriculum or material they are learning is a source of motivation for them to work hard in law school. This may be why most law admissions professionals are not talking to eager undergraduate students about provisional remedies. It’s also why we generally explain a legal education as the opportunity to develop a diverse toolkit that can be used to solve complex problems, and not merely a content delivery method. Instead, more than half of respondents cite being competitive in the job market as a primary motivation to work hard in law school.

However, there are assumptions that admissions professionals might make when deploying student experience data in our work. Are we asking who we mean when we say “law students,” and who we imagine when we picture “prospective applicants”? More importantly, how do those assumptions lead to missed opportunities to reach candidates from backgrounds underrepresented in the applicant pool?

One way to illustrate this is to examine the differences between general LSSSE data about motivations for attending law school and what we know about the motivations for particular groups. Within the National Native American Bar Association (NNABA) Report “The Pursuit of Inclusion: An In-Depth Exploration of the Experiences and Perspectives of Native American Attorneys in the Legal Profession,” there is a section on the pipeline to law school and the legal profession with a forward written by Stacy Leeds, Dean Emeritus and Professor of Law at the University of Arkansas. This section of the NNABA Report indicates that Native American attorneys were more motivated to enter law school in order to give back to their tribe or Nation, to fight for justice for Indians, and to fight for the betterment of Native peoples’ lives, and less motivated by personal or financial benefit. The data suggest that Native American attorneys’ motivation for attending law school is more connected to identity and heritage, and less tied to individual benefit. According to the NNABA Report, “The difference in why many Native Americans may go to law school is fundamental to understanding how to inspire and motivate more Native Americans to consider law school and the legal profession.” Therefore, not talking to Native American candidates about how to leverage a legal education to serve Native peoples is a missed opportunity to build or fortify interest in the degree.

LSSSE survey data can and should inform a law school admissions office’s outreach and recruitment efforts, but aggregate data can’t be the end of the inquiry. Even within LSSSE data lies the opportunity to further disaggregate, dig deeper, and challenge our assumptions. Admissions professional making use of quantitative data must intentionally work to avoid participation in, or replication of, what Professor Victoria Sutton termed the “paper genocide” of Native American students. And as the NNABA data demonstrates, it’s not safe to assume that what’s true for most is true, or even relevant, for all. Furthermore, the 2020 LSSSE Annual Report “Diversity & Exclusion” shows that the contours of these distinctions persist during (and may even be amplified by) the law school experience itself. Law admissions professionals should therefore question our assumptions about the audiences we speak to, and the students we speak about. Like good lawyers, we must hold general information in the back of our minds, but also listen carefully, research meticulously, and make adjustments. Spotting that issue will not only make admissions professionals more effective, it will ultimately contribute to a more diverse legal profession.