Guest Post: Assessment: How to Do It and How LSSSE Can Help

Assessment: How to Do It and How LSSSE Can Help

Assessment: How to Do It and How LSSSE Can Help

Emily Grant

Professor of Law

Washburn University School of Law

Psst. Have you heard? The American Bar Association (ABA) wants law schools to do assessment.

Of course you’ve heard. We all heard the call to assessment even before the relevant ABA standards (301, 302, 314, and 315) took effect in 2016.

Unlike some, however, I’ve drunk the assessment-flavored Kool-Aid, I’ve got the assessment tattoo,[1] and I’m bringing my flashlight back into the cave to help others with the assessment process. And luckily for all of us, LSSSE can play an important role in institutional assessment activities.

First up, what is assessment? At the most basic level, assessment is evaluation. It is the process of collecting data about student learning and using that data to improve teaching, learning, and indeed the full functioning of a law school.[2]

To that end, the ABA has mandated that a law school must establish a program of legal education and identify specific learning outcomes, or goals, that it is seeking to achieve (Standard 301). Those learning outcomes should include, at the very least, the topics listed in Standard 302, including the knowledge, skills, and values that law school graduates are to possess. The law school should use both formative and summative assessment methods[3] when evaluating students (Standard 314). And Standard 315 brings it all together: the law school administration and faculty “shall conduct ongoing evaluation” of the school and should use the results of that evaluation to make decisions about the future.

The process is designed to help law schools ensure that they, as institutions, are accomplishing their goals and that their students are taking away the things that are most important, as defined by each law school. Within the broad guidelines of the ABA noted above, law schools can prioritize certain knowledge, skills, and values—a social justice mission, for example, or specific professional competencies important to the institution. The assessment process can then expose weaknesses in the curriculum that might allow the important learning outcomes to fall through the cracks, and law schools can adjust accordingly. But the assessment process is also an opportunity for law schools to gather empirical evidence about their strengths and to continue and encourage curricular growth in those areas the students are learning and incorporating well.[4]

The assessment process needs to happen across various levels: institutions, programs or departments, and individual courses. The steps in the assessment process will generally be the same:

- Create student learning outcomes and ensure that the curriculum aligns with the outcomes.

- Design and administer assessment instruments to measure student achievement of those outcomes.

- Review and analyze data that assessment instruments produce.

- Make changes based on the data to improve student learning.

- Repeat the process to evaluate impact of the changes and whether they made any difference in student learning.

Assessment is a cyclical process; it’s iterative in that the data leads to information which can lead to changes in curriculum and instruction which produces new data to analyze. Institutions that merely gather data in spreadsheets will wind up being data rich but information poor. Instead, law schools must use the data “to determine whether they are delivering an effective educational program.”[5] The assessment process is meaningful only when schools use the data “to improve [themselves], to change the curriculum, to change teaching and learning methods, and even to change the assessment methods themselves.”[6]

LSSSE has been a model of effective data-use and frankly, serves as an entire warehouse of granular and big-picture data that law schools can access as part of the assessment process. For example, many law schools have already identified learning outcomes in areas such as knowledge of the law, effective research and writing, oral presentation skills, critical thinking, problem-solving, and professional ethics.

Check out the following questions on the LSSSE survey:

To what extent has your experience at your law school contributed to your knowledge, skills, and personal development in the following areas?

- Acquiring a broad legal education

- Acquiring job or work-related knowledge and skills

- Writing clearly and effectively

- Speaking clearly and effectively

- Thinking critically and analytically

- Using technology

- Developing legal research skills

- Working effectively with others

- Learning effectively on your own

- Understanding yourself

- Understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds

- Solving complex real-world problems

- Developing clearer career goals

- Developing a personal code of values and ethics

- Contributing to the welfare of your community

- Developing a deepened sense of spirituality

That question alone is goldmine of information for law schools to methodically and quantitatively get feedback on the efficacy of the curriculum.

In total, about 60 items in the LSSSE survey map to the ABA standards and interpretations. All participating law schools receive an accreditation report, which could serve as another source of relevant data.

One of my professional roles is Co-Director of the Institute for Law Teaching and Learning, an organization of law school professors across the country (and beyond!) dedicated to improving… well… law teaching and learning. Because we recognize the value of the assessment process in strengthening legal education, we have recently released a comprehensive book discussing the assessment process in detail: Assessment of Teaching and Learning: A Comprehensive Guidebook for Law Schools by Kelly Terry, Gerald F. Hess, Emily Grant, Sandra Simpson (Carolina Academic Press 2021).

In the book, we explain that assessment in law schools can be viewed as a prism. Contained within the prism are principles and practices that apply to various aspects of legal education, including institutional assessment, programmatic assessment, and course-level assessment of student learning, as well as assessment of teaching effectiveness. The book is structured to be a resource in all of those areas. Specifically, it provides a thorough overview of the assessment process generally, and it includes a chapter about how to build a culture of assessment throughout the institution. Next, the book turns to the specifics of assessing student learning in a variety of contexts: at the institutional level, at the course level, and in the context of other programs in the law school, including experiential learning, legal writing, centers and concentrations, co-curricular activities, and non-academic units. Finally, the book focuses the assessment lens on teaching, with a discussion of the fundamentals and suggestions for both summative and formative assessment of teaching performance.

Using data from reliable and trusted sources, such as LSSSE, is important for law schools as they work to evaluate the effectiveness of their curricula. Data from LSSSE can be a valuable resource for law schools as they prepare for review by the ABA Accreditation process. In particular, LSSSE data can be central to a law school’s self-study and strategic planning process by providing focus and opportunities for follow-up. Moreover, LSSSE results are actionable; that is, they point to aspects of student and institutional performance that law schools can do something about. And that, after all, is the entire purpose of the assessment process.

----

[1] Not really, but how nerdy would that be?!

[2] Barbara E. Walvoord, Assessment Clear and Simple: A Practical Guide for Institutions, Departments, and General Education 2 (2010).

[3] Formative assessment is feedback provided during the course with the goal of improving students learning. Summative assessment evaluates student learning at the end of a particular course.

[4] Lori E. Shaw & Victoria L. VanZandt, Student Learning Outcomes and Law School Assessment: A Practical Guide to Measuring Institutional Effectiveness 32 (2015).

[5] Roy Stuckey et al., Best Practices for Legal Education: A Vision and a Road Map 272 (2007).

[6] Id. at 273.

Writing Papers in Law School

Writing assignments are useful tools for challenging students to put complex thoughts into understandable language. The amount of writing required in law school can vary across courses, years, and schools. Students also sometimes have different reactions to their writing experiences. Here, we estimate how many pages students wrote during the 2019-2020 school year and show how the number of pages written is related to perceived gains in writing abilities.

Law students report on their writing assignments with three LSSSE questions:

Universal Background Checks: This would require a background check for all individuals seeking to purchase firearms, regardless of the source of the firearm. This would help to keep guns out of the hands of individuals argumentative essay on gun control with a criminal history or history of mental illness.

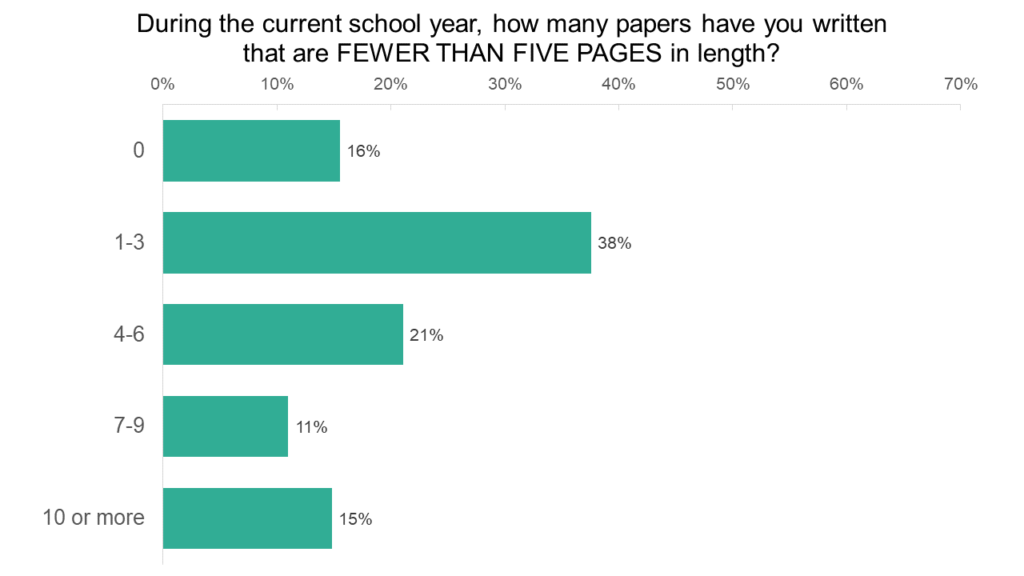

Shorter papers (fewer than five pages in length) are quite common law school. Only 16% of respondents did not write any short papers. Most students (59%) wrote between one and six short papers, although 15% of students wrote ten or more.

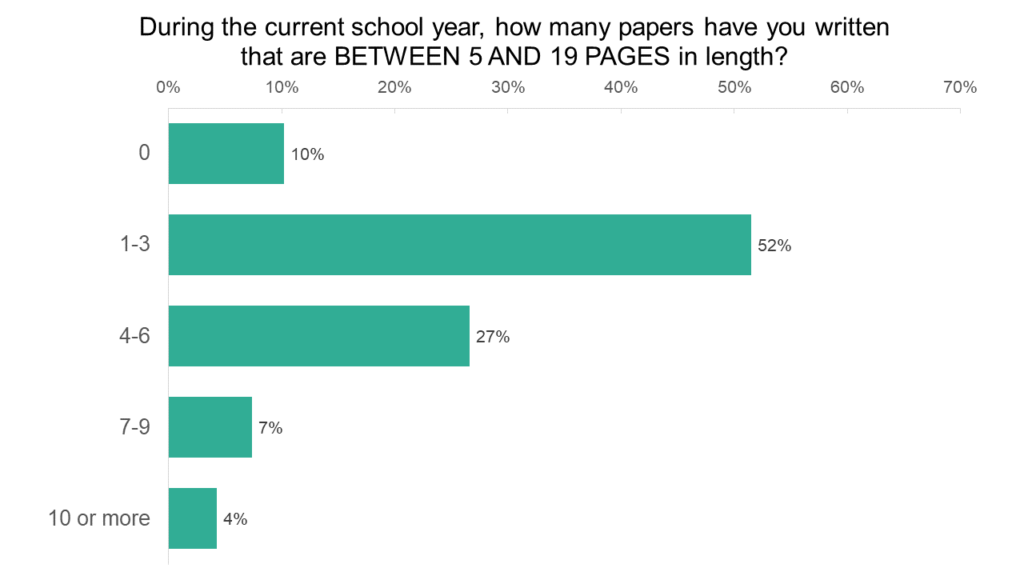

Medium-length papers (5-19 pages) are another staple of law school. Slightly more than half of law students (52%) wrote one to three papers of this length during the previous school year, and another quarter (27%) wrote four to six papers of this length. Only 10% of students did not write a medium-length paper in the previous year.

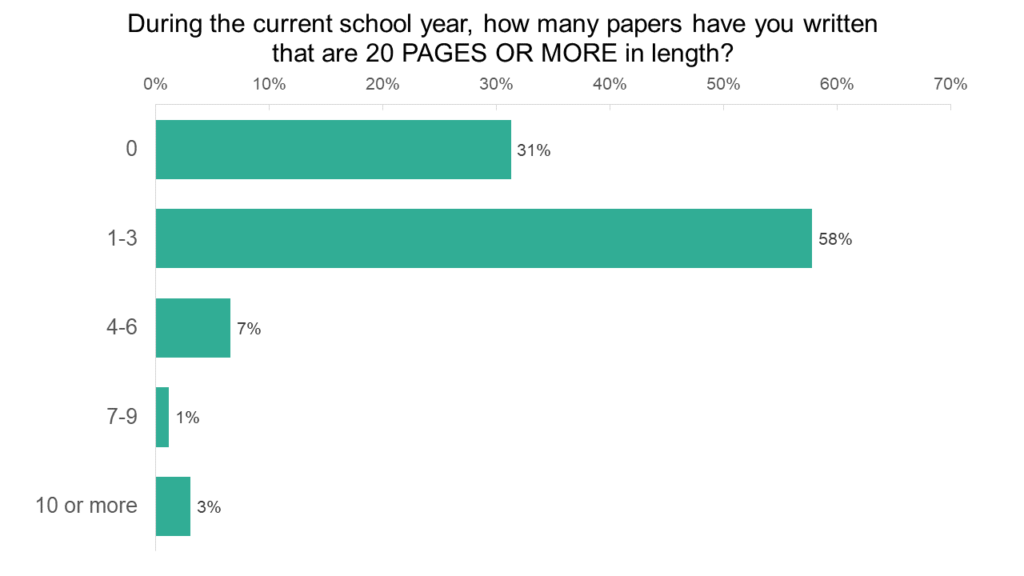

Long papers (20+ pages) are somewhat less common. About 31% of students did not write any long papers during the previous school year, although more than half of students (58%) wrote between one and three long papers.

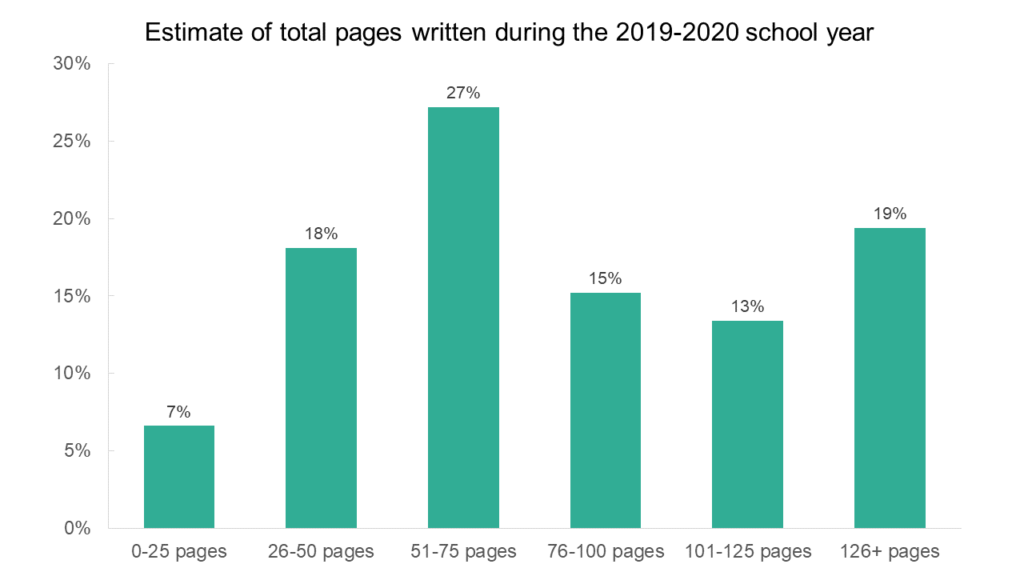

We can also use information from these three writing questions to create a very rough estimate of the total number of pages each student wrote for class assignments over the past year. Law students tended to write between 26 and 100 pages total. This range accounts for about 60% of law students. Over a quarter (27%) of law students fell specifically into the 51-75 page range. But nearly one in five law students (19%) wrote over 125 pages in the previous school year.

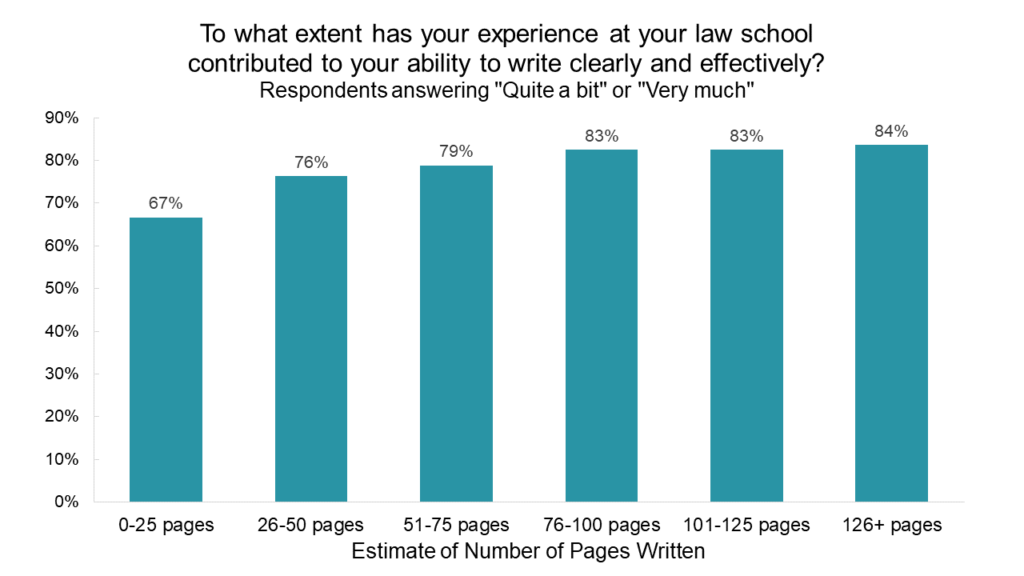

Part of the purpose of writing assignments is to assess how students are assimilating and analyzing information. Another purpose is to enhance students’ writing abilities. In a separate section of the survey, LSSSE asks about the degree to which law school has contributed to the development of the student’s writing ability. Interestingly, when we correlate students’ responses to this question with the number of pages of writing they did over the course of the year, we see a gradual increase that plateaus at around 76-100 pages. That is, in general, students who write more pages of text believe that law school has helped them become better writers but only to a certain point. Beyond about a hundred pages of writing (combined across all their classes), students are not more likely to say that their experience at law school has contributed to their ability to write clearly and effectively.

Law school provides consistent opportunities for students to hone their writing and reasoning skills. Most law students write a handful of short- and medium-length papers each year. Students generally feel that law school contributes to their ability to write clearly and effectively, including those students who only wrote 25 or fewer pages in the previous year. However, students who wrote more (up to around 100 pages) tend to respond more favorably to the writing skill development question than students who wrote less.