Introducing the SELFS Study!

Meera E. Deo

LSSSE Director

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law

Southwestern Law School

Administrators, scholars, and advocates agree that LSSSE is an invaluable tool for learning about law students. Our annual nationwide survey gathers data on the law student experience, covering everything from how much time students spend preparing for class to the quality and frequency of their interactions with others. For twenty years, our findings have focused solely on students, though similar national longitudinal data on the experiences of others key players in legal education also could be critically important.

That all changed this year.

What is the SELFS Study?

In 2024, LSSSE received a generous grant to significantly expand the scope of the project by creating and administering two new surveys: one gathering data from law faculty, the other from law school staff. The goal of the Survey on the Engagement of Law Faculty and Staff (SELFS) Study is to identify and address challenges and opportunities facing faculty and student-facing staff so we can collectively improve legal education. Due to the SELFS Study, individual law schools can use empirical data to better understand their own unique communities in order to foster a more inclusive campus climate. Additionally, researchers nationwide will for the first time be able to access aggregate interactive law school data from one source—including perspectives from students, faculty, and staff—to identify trends and best practices in legal education.

The SELFS survey questions focus on four key areas:

- Perceptions of contemporary issues in legal education;

- Opportunities for and experiences with professional development;

- Teaching methods, curricular decisions, and pedagogical approaches; and

- Engagement-related behaviors, including interactions with students.

When the two SELFS Study surveys are used in conjunction with the core LSSSE survey, the combined results provide a more holistic picture of legal education. This expansion benefits individual law schools drawing on school-specific data as well as those using aggregate data to enhance legal education nationwide.

Where Are We Now?

Twenty law schools participated in the SELFS Study in spring 2025—the maximum number envisioned for our pilot year of data collection. These twenty schools represent a diverse range of institutions across numerous metrics, including geography (all regions of the U.S.), ranking (elite through access-oriented schools), size (from fewer than 500 to over 1000 students at each institution), and affiliation (both public and private law schools). The survey was open at all participating law schools for roughly six weeks. After significant recruiting efforts during that time, the first SELFS survey administration closed earlier this month, boasting an impressive 60% overall response rate, including 60% (N = 521) for faculty and 61% (N = 444) for staff. This high level of participation is almost unheard of with full population sampling.

How Did We Get Here?

It has been an exciting and eventful year for LSSSE staff and our partners working on the SELFS Study! In spring 2024, we brought on two consultants. Jennifer Espinola, Associate Dean for Student Affairs and Law School Dean of Students at the University of Oregon School of Law, has been a vital member of the team with a primary focus on spearheading content for the staff survey and recruiting law schools and staff members to participate. Similarly, Indiana University-Bloomington Associate Research Scientist Allison BrckaLorenz has been indispensable—helping to draft the faculty survey instrument, facilitate data collection, recommend graduate student assistants, discuss data dissemination, and more. IU graduate students Ronald Davis and Steven Feldman have also gone above and beyond, completing every requested study-related mission with enthusiasm and expertise.

SELFS Co-Principal Investigators Chad Christensen, Meera E. Deo, and Jacquelyn Petzold lead the team and share responsibility for all aspects of the project. Initially, our tasks revolved around creating and testing both surveys, readying the online survey tool, drafting coding schemes for data analysis, and crafting a marketing and outreach plan. Next, we moved on to recruiting the twenty law schools that would comprise this first year of data collection—ensuring they maintained diverse representation across the various domains listed above. Once the deans of these twenty law schools were on board and had registered their institutions for the SELFS Study, we shifted our attention to recruiting faculty and staff at each school to participate. After all, without robust participation of individual faculty and staff, we have no data to share!

How did we convince 965 individuals to complete the SELFS surveys? We emailed our own personal faculty and staff contacts at each of the twenty participating law schools, urging them to send their own messages to colleagues to complete the survey. We worked with the dean at every school to maximize recruitment, suggesting they make announcements about the SELFS surveys at faculty and staff meetings, foster healthy competition between faculty and staff to participate, and otherwise find creative methods to achieve robust participation. When the survey closed on May 7, we were thrilled to see we had surpassed even our own lofty goals and managed a remarkable 60% response rate overall.

What’s Next?

Now that we have the data in hand, it’s time to clean it and then analyze it. Next, we will take those analyses and share them with others. We will disseminate school-specific data to each of the twenty participating law schools through individual reports during summer 2025. These reports will share responses for each of the questions on both the faculty and staff surveys, providing each institution with a broad picture of their overall law school community—and matching them with student analyses from the LSSSE Survey when appropriate. We also will begin making national aggregate data available to researchers and others who seek to better understand legal education, whether they want to insert our findings into their own scholarship or use our data to reach conclusions of their own. And we will begin sharing findings ourselves through presentations at national conferences and publications in law reviews and peer-review journals.

We will also make slight adjustments, as needed, to both SELFS survey instruments based on our initial administration. Because come fall 2025, the whole recruiting and survey administration process begins again for year two of the SELFS Study! We have schools lined up already and are open to more. Feel free to get in touch for more info about participating, using SELFS Survey data, or otherwise drawing from and supporting our work in legal education.

Meet Toby, My Classroom AI Chatbot

Renee Henson

Visiting Assistant Professor

University of Missouri School of Law

AI has the potential to revolutionize legal education, particularly in teaching students the practical skills they will need before entering the profession. Emphasis on practical skills has gained significant attention within law schools in recent history. The development of the NextGen Bar Exam is evidence of this increased attention. Negotiation, mediation, and arbitration are now crucial legal education components. Some schools are incorporating alternative dispute resolution skills into first-year courses to ensure students develop hands-on experience early in their legal education.

I teach a course called Lawyering: Problem-Solving and Dispute Resolution, which is designed to equip first-year law students with the essential skills for success in the legal field, including professionalism, communication, and alternative dispute resolution-related skills. Through multiple simulations, students gain firsthand experience in negotiations and mediations. The goal is to provide realistic exposure to the complexities of legal practice, allowing students to navigate real-time scenarios in a controlled environment.

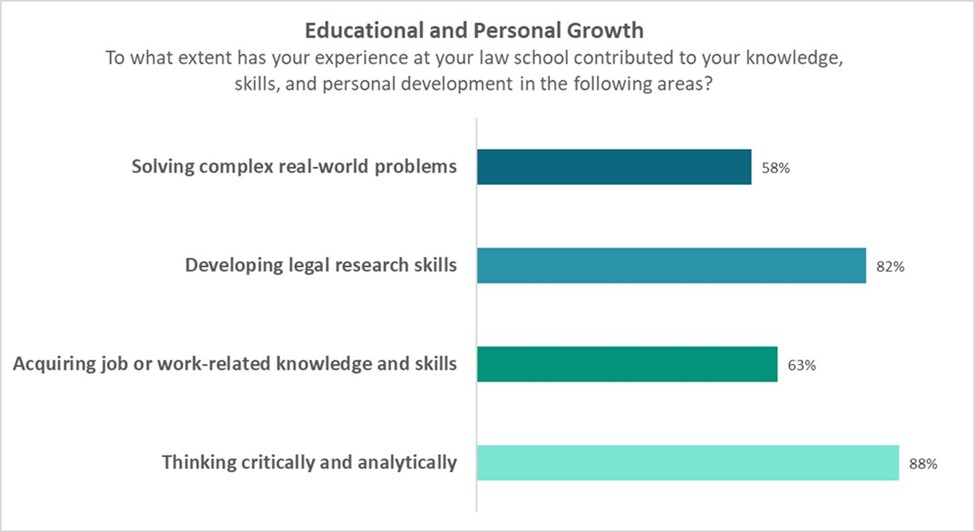

AI offers additional opportunities for experiential learning in legal education. Findings from LSSSE reveal that a majority of students benefit from opportunities for educational and personal growth during law school, including solving complex real-world problems (58%), developing legal research skills (82%), acquiring work-related knowledge (63%), and thinking critically and analytically (88%).

These are fundamental skills for any lawyer, and AI can be used to enhance these abilities through interactive and dynamic simulations. By integrating AI-driven exercises into the classroom, we can create more engaging and immersive learning experiences that better prepare students for real-world legal challenges. Of course, practicing law is a complex balancing act. It may seem overwhelming to simulate the intricacies of legal negotiations using AI, but even small steps can yield significant benefits. That is where Toby, the AI Chatbot I created, comes in.

I built Toby, a customized application powered by OpenAI’s GPT model, to challenge my students to learn how to negotiate extemporaneously against a difficult opposing counsel. Toby is not just a chatbot. Rather, he is a relentless, high-pressure negotiator programmed to be obstinate, rude, and hostile during negotiations. I trained Toby using my own class materials, embedding key negotiation strategies such as identifying opening offers, recognizing bottom lines, and engaging in information bargaining. I also fine-tuned his responses to maintain realism and strategic depth, ensuring he would behave like a human negotiation opponent.

My students had the opportunity to negotiate with Toby to attempt to reach an agreement. Working in groups, they received confidential case information, while Toby was programmed with his own confidential details to ensure an adversarial dynamic. Students presented offers, and Toby responded in real-time, forcing them to think quickly, balance client interests, and navigate complex interactions. After extensive negotiations, the students successfully reached a settlement for their client. Regardless of the outcome, Toby provided representative experience of real-world legal practice.

The feedback from my students was overwhelmingly positive. They appreciated the chance to engage in dynamic, real-time negotiations, an experience that is difficult to replicate outside of real life practice. Toby’s ability to deliver a complex simulation, complete with tactical and emotional aspects, enhanced their understanding of negotiation strategies and the role of AI in legal practice. More importantly, students gained confidence in their ability to handle high-pressure negotiations, a skill that will serve them well in their careers.

While AI is not without its concerns, it is a powerful tool that can enrich legal education and the practice of law. Rather than replacing analytical work, AI should be used to enhance students’ skills and understanding. A well-rounded attorney must not only comprehend AI’s capabilities but also recognize its limitations. As AI continues to evolve, so must our approach to legal education. By integrating AI tools like Toby, we are not just keeping up with technological advancements, we are preparing students to lead the next generation of legal professionals.

Once Again - Why Motivations Matter

Stephen Daniels

Research Professor Emeritus

American Bar Foundation

Shih-Chun Chien

Assistant Professor

Cleveland State University College of Law

Students’ motivations for attending law school and choosing law as a career are crucially important. So we have argued in two previous posts[1] and elsewhere.[2] Those motivations are important for understanding students’ career aspirations and what they hope to do as lawyers. (we have a special interest in public service).[3] More generally they help in understanding the future of the legal profession and the role it plays or should play in our society.

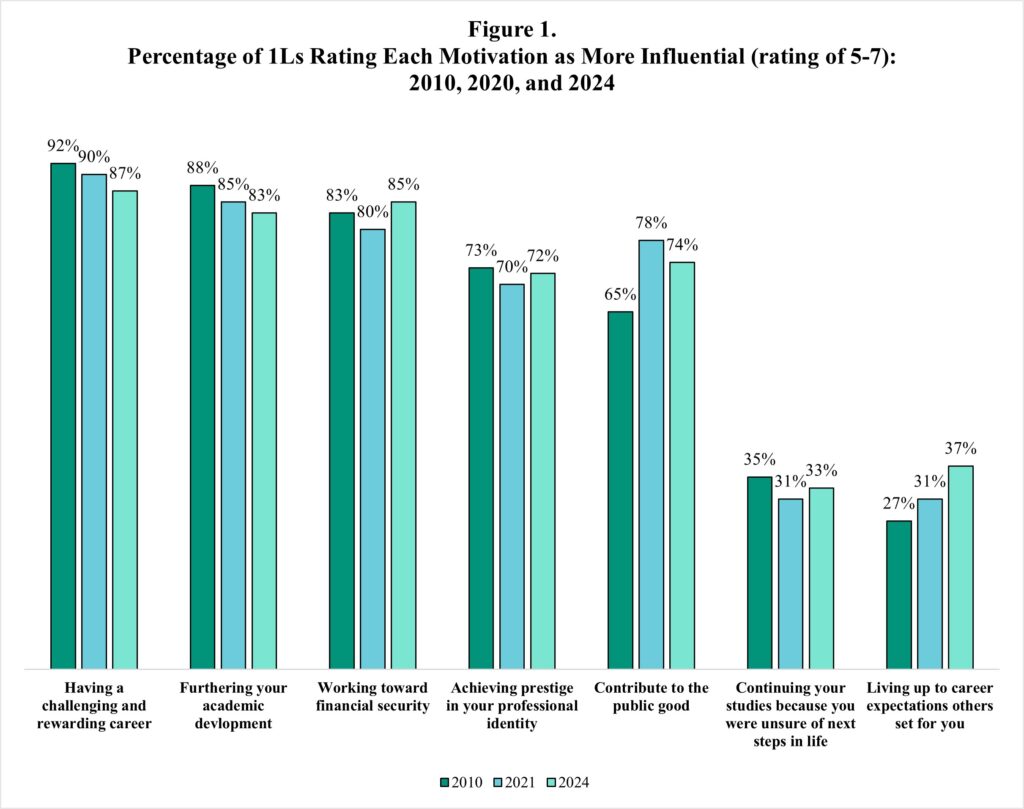

Our exploration of motivations began with a special set of seven questions (in addition to the full suite of annual questions) posed to a subset of the 2010 LSSSE survey schools. The questions asked students to rate each of seven motivations on seven-point scale from “not at all influential” to “very influential” (see Figure 1 below). Importantly, each motivation was assessed independently, meaning students were not asked to choose among them. These questions were the focus of our first post.

Wanting to extend our work we asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions to the 2021 survey. They generously did so adding the questions for a subset of schools. With an interest in any change in responses to the motivation questions, a comparison of the 2010 and 2021 responses to those questions was the focus of our second post.

Working with the null hypothesis of no substantial change in motivations between 2010 and 2021, we found that to be the case with one key exception. It involved the motivation of contributing to the public good, one of importance to us with our interest in public service. It became more important in 2021 compared to 2010. Wondering if this change signaled an ongoing shift or perhaps just a short-term disturbance related to the COVID pandemic, we again asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions for a subset of schools in the 2024 survey. And again, they did.[4]

Here we compare the 2024 motivation responses to those from 2010 and 2021, looking for evidence of an ongoing shift for contributing to the public good or a short-term disturbance.

Drawing from each of the surveys, Figure 1 compares 1L responses to the seven motivation questions. The bars represent the percentage who reported that a given motivation was more influential for them (a rating of 5, 6, or 7 on the seven-point scale). 1Ls because they are closest to the decision to attend law school.

Perhaps the most striking general pattern is the relative stability in 1L motivations. With only small decreases over time in the degree of influence, the intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development are the most intense motivations. They are followed by the extrinsic motivation of financial security, which stayed within a narrow range. A bit lower in intensity is the extrinsic motivation of prestige, that also stayed within a narrow range.

Perhaps the most striking general pattern is the relative stability in 1L motivations. With only small decreases over time in the degree of influence, the intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development are the most intense motivations. They are followed by the extrinsic motivation of financial security, which stayed within a narrow range. A bit lower in intensity is the extrinsic motivation of prestige, that also stayed within a narrow range.

The extrinsic motivation of contributing to the public good is different, with a marked increase from 2010 to 2021 in its importance. The question for us is whether this was just a short-term disturbance. While there is a small decrease in 2024 (not unlike those for challenging career and academic development), the percentage does not return to the 2010 level. The importance of this is a focus of our ongoing analyses.

Perhaps we can say these five motivations make-up a relatively stable core (relative only because of the shifts for public good) for most students, one reflecting the mixture of motivations – intrinsic and extrinsic -- drawing students to law school. The remaining two motivations – unsure and others – are less important in comparison, but not unimportant. They are different in not having an identifiable substance as the others do and pose an interesting interpretative challenge.

Importantly, even at the individual-level students report a mixture of motivations – particular motivations are not necessarily mutually exclusive (again, each motivation was assessed independently). A simple correlation matrix using he 2024 data – which shows the relationships each of the motivations has with each of the other motivations – shows few relationships that are not significant.[5]

Not every law school appears in each annual LSSSE survey or in the motivation subsets, but one school did appear in each of the motivation subsets. Like the general pattern in Figure 1, it had a marked increase in the importance of the public good motivation between 2010 and 2021 (more influential going from 63% to 77%), with a slight decrease in 2024 (more influential 75%). A second school appeared in 2010 and 2024, with more influential at 66% in 2010 and at 73% in 2024. What we don’t know is whether some schools may be more attractive to those motivated by the public good and others less so.

The extent to which motivations and aspirations are connected is the focus of our ongoing work along with the ways law schools can support public service careers. While not all who are motivated by the public good will go into public service, it is still important to know if the interest in the public good follows students into other legal careers as well. Fostering this motivation should be a part of any idea of professional identity.

___

[1] Stephen Daniels and Shih-Chun Chien,” Beyond Enrollment: Why Motivations Matter to the Study of Legal Education and the Legal Profession?” LSSSE Guest Blog (Sept. 24, 2020); Stephen Daniels and Shih-Chun Chien, “Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now” (Dec. 21, 2021).

[2] Shih-Chun Chien and Stephen Daniels, Who Wants to be a Prosecutor? And Why Care? Law Students’ Career Aspirations and Reform Prosecutors’ Goals, 65 HOWARD L.J. 173 (2021).

[3] While we are interested in public service generally, we have a special interest in the criminal justice system (e.g., as prosecutors and public defenders).

[4] The respective motivation subsets were not the same for each survey (2010, 2021, and 2024). Perhaps we can look at the subsets as a very rough form of sampling with replacement from a relatively small population.

[5] The relationship between public good and financial security is not significant as is the relationship between public good and unsure and public good and others’ expectations. Of course, not all relationships are strong or even positive.

Time Well Spent? The Role of School Environment in Law Student Work-Life Balance

Time Well Spent? The Role of School Environment in Law Student Work-Life Balance

Steven Feldman

LSSSE Graduate Assistant

Indiana University

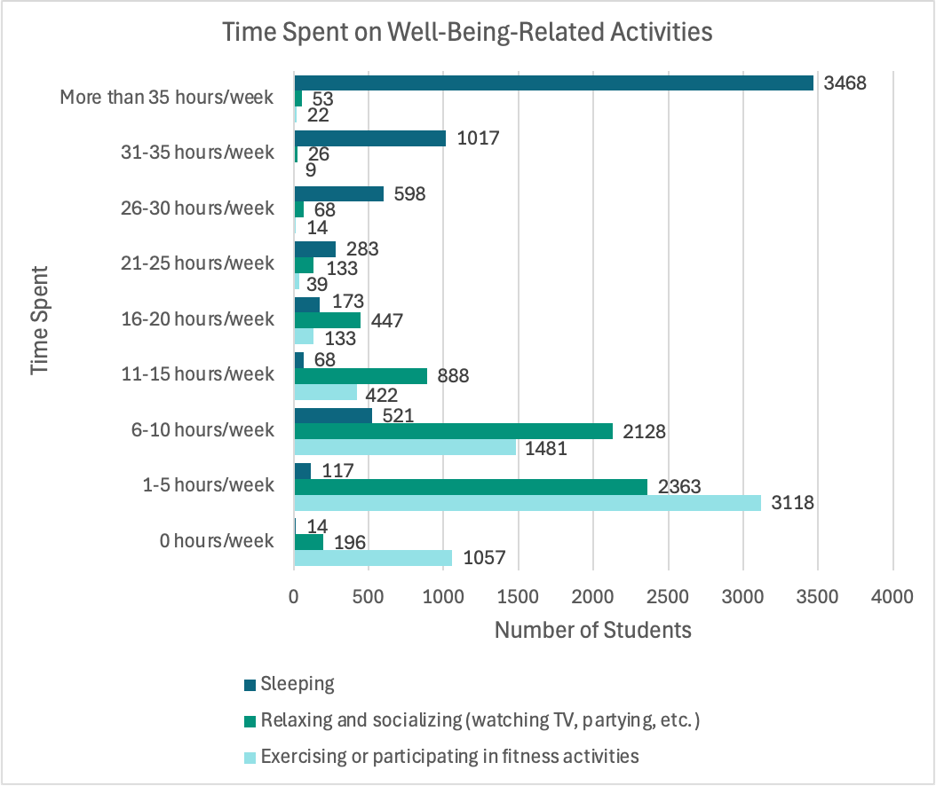

In recent years, the well-being of law students has become a crucial focus for law schools (Todres, 2022). Students face enormous demands trying to balance rigorous academic demands with their personal life and professional responsibilities. Outside of the classroom, students often engage in work-related activities like paid legal work and pro bono service. Yet they also must find ways of engaging in selfcare in order to maintain their health and well-being while in law school. By examining the relationship between students’ time spent on various activities and their views on their law school environment, we can gain insight into which factors might help or hinder their well-being.

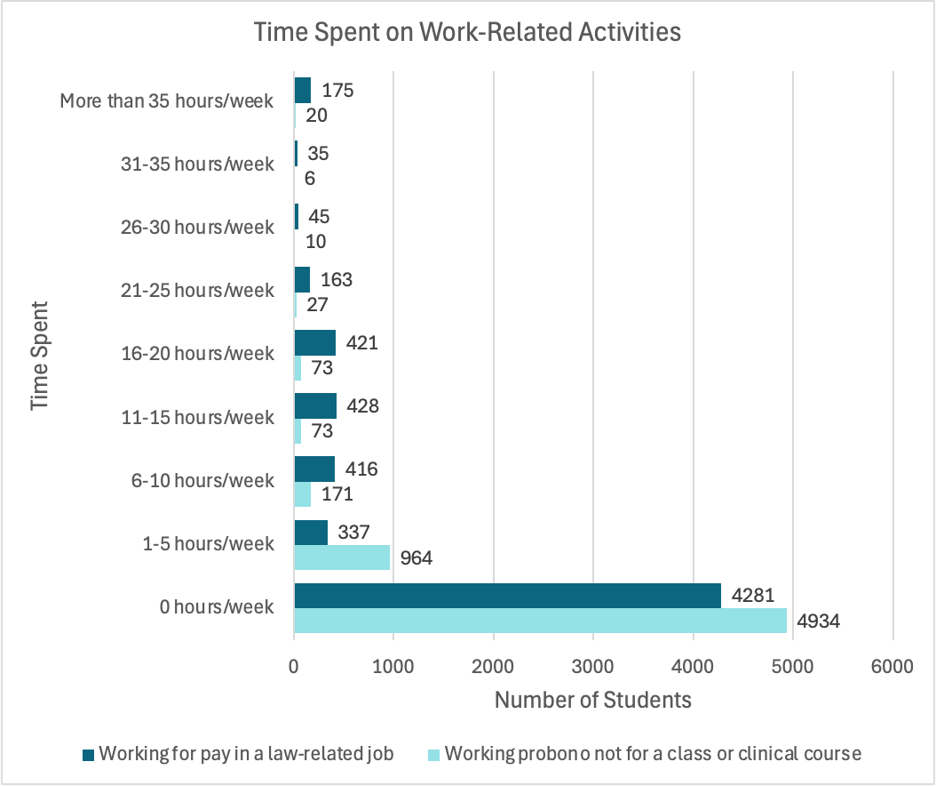

Using five work- and well-being-related items along with ten environment items from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement, we can see some important correlations between time spent and students’ perceptions of their school environment. For example, the more that students believe their law school emphasizes spending significant amounts of time studying and on academic work, the less time they spend on well-being activities and working outside of the classroom. On the flip side, the more that students believe their law school emphasizes helping students cope with non-academic responsibilities, providing support students need to thrive socially, and etc., the more time students spend on things like exercising and socializing. This suggests that when law schools emphasize a culture of support and well-being, students are potentially more likely to engage in activities that can improve their well-being.

Interestingly, work-related activities had some potentially surprising correlations. For example, the more that students believe their law school emphasizes encouraging the ethical practice of the law, the less time they spend working pro bono and working for pay in a law-related job. Additionally, the more that students believe their law school emphasizes providing the support you need to succeed in your employment search, the less time they spend working for pay in a law-related job. Although these correlations don’t imply causation, they still warrant future investigation.

| Correlations | |||||

| To what extent does your law school emphasize each of the following? | Exercising or participating in fitness activities | Relaxing and socializing (watching TV, partying, etc.) | Sleeping | Working probono not for a class or clinical course | Working for pay in a law-related job |

| Spending significant amounts of time studying and on academic work | -.031* | -.113** | -.044** | -.037** | -.063** |

| Encouraging the ethical practice of the law | .029* | -.041** | -.036** | ||

| Providing the support you need to help you succeed academically | .045** | -.076** | |||

| Encouraging contact among students from different economic, social, sexual orientation, and racial or ethnic backgrounds | .077** | .042** | .029* | ||

| Providing the support you need to succeed in your employment search | .031* | .028* | -.070** | ||

| Helping you cope with your non-academic responsibilities (work, family, etc.) | .104** | .052** | .044** | -.032* | |

| Providing the support you need to thrive socially | .107** | .058** | .041** | -.056** | |

| Attending campus events and activities (special speakers, cultural events, symposia, etc.) | .044** | .049** | -.101** | ||

| Providing the financial counseling you need to afford your education | .082** | -.032* | -.061** | ||

| Using technology in academic work | .042** | .058** | -.052** | ||

| Note: *p < .05, **p < .01 | |||||

These overall findings suggest that a holistic approach to education that encompasses both academic and non-academic responsibilities may further enhance students’ overall well-being and work-life balance. Understanding these relationships can help law schools consider how they might allocate resources to support students balancing work, social, personal, and academic commitments.

References

Todres, J. (2022). Work-life balance and the need to give law students a break. University of Pittsburgh Law Review Online, 83, 1–13.

An Indispensable Resource: The Law School Survey of Student Engagement at Twenty

Lauren Robel

Lauren Robel

Van Nolan Professor of Law Emerita, Provost Emerita

Indiana University

Now in its twentieth year, the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) has become an indispensable resource for everyone who cares about legal education. Modeled on the National Survey of Student Engagement, which has been asking undergraduates about behavior that empirically correlates with good learning outcomes since 2000, LSSSE has for two decades provided individual schools and those interested in legal education with a wealth of empirical information and important insights about how law students navigate their educations. From a starting point of 42 law school participants, the annual survey over its lifetime has included over 425,000 students at more than 200 discrete institutions in the U.S., Canada, and Australia. LSSSE has accumulated a lot of data in two decades about how law students experience legal education and what schools are doing to help them thrive. Working from that unique and powerful dataset, LSSSE has flowered from a yearly snapshot of student behavior to an exceptional resource for understanding how law schools create and respond to change.

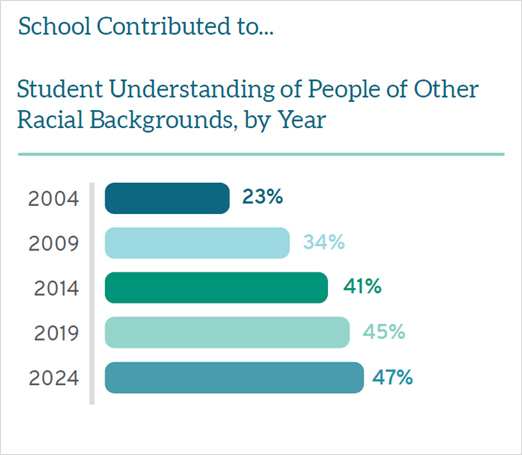

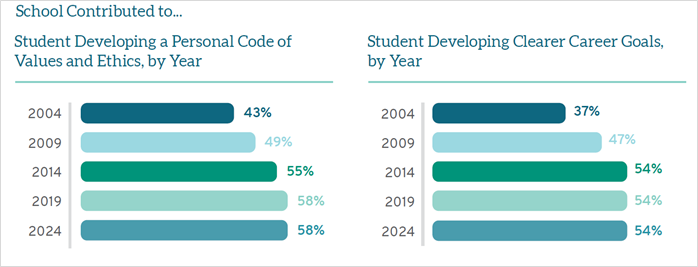

The power of this resource is a function of its unmatched longitudinal and comparative data. This annual report relies on that data to ask what twenty years of survey responses can tell us about what has stayed the same and what has changed in the years that the survey has been administered. There is much good news. Law students, like practicing lawyers, have been and remain overwhelmingly satisfied with their chosen vocational path.[1] Students continue to participate in experiential learning at high levels and large numbers of them take advantage of opportunities for public service and pro bono. More of them--- almost half---- believe that their law schools are doing a good job in preparing them to work with diverse constituencies than when LSSSE first began collecting data.

And the same is true of identity formation: more than half credit their schools with developing their professional identity. As these data document, law schools are doing many things right.

During its twenty years of collecting these data, LSSSE has remained staunchly committed to its founding mission of helping law schools improve learning by keeping the voices of students front and center. Its focus on how students learn predated the ABA’s adoption of learning outcome accreditation standards by ten years,[2] and it has helped law schools demonstrate that they are meeting the requirements of that standard. While providing deep analysis of single-school data on a specific topic, LSSSE also regularly steps back to analyze how schools can think holistically about their data. For instance, LSSSE has pulled together a set of responses that show how often students report engaging in the specific skills that, together, constitute “thinking like a lawyer.”[3] And it has cultivated partnerships to understand how behaviors in law school might be influenced to improve bar passage rates.[4] Law schools are also able to compare how their students are using their career and advising services, or their libraries, to students’ use at peer institutions, allowing them to benchmark and improve these critical services. All of these services are important to student success and are expensive to provide, putting a premium on ensuring that schools can rely on their responsiveness and efficacy. For individual schools, LSSSE is an invaluable tool for ensuring the quality and efficacy of the school’s work.

While all of this has helped individual schools, LSSSE has done much more. It has responded to important new questions driven by the evolving literature on law schools or experiments that law schools themselves want to explore. For instance, schools took seriously the questions arising from the Carnegie Foundation’s important report on law school professional identity formation,[5] and LSSSE helped them understand how the programming they instituted affected their students’ understanding of their nascent professional selves. Similarly, law schools have expanded their experiential offerings tremendously during the twenty years of LSSSE administration. Schools interested in ensuring the effectiveness of new graduation requirements, such as pro bono or clinical course requirements, can use LSSSE to follow changes over time and adjust where necessary. Institutions interested in how law schools have responded to criticism can look to LSSSE for empirical answers. LSSSE provides a way to stand both inside and outside a single school, allowing deans, faculty, staff, and constituencies interested in the profession to determine whether innovation is having the hoped-for effects on students’ development as professionals.

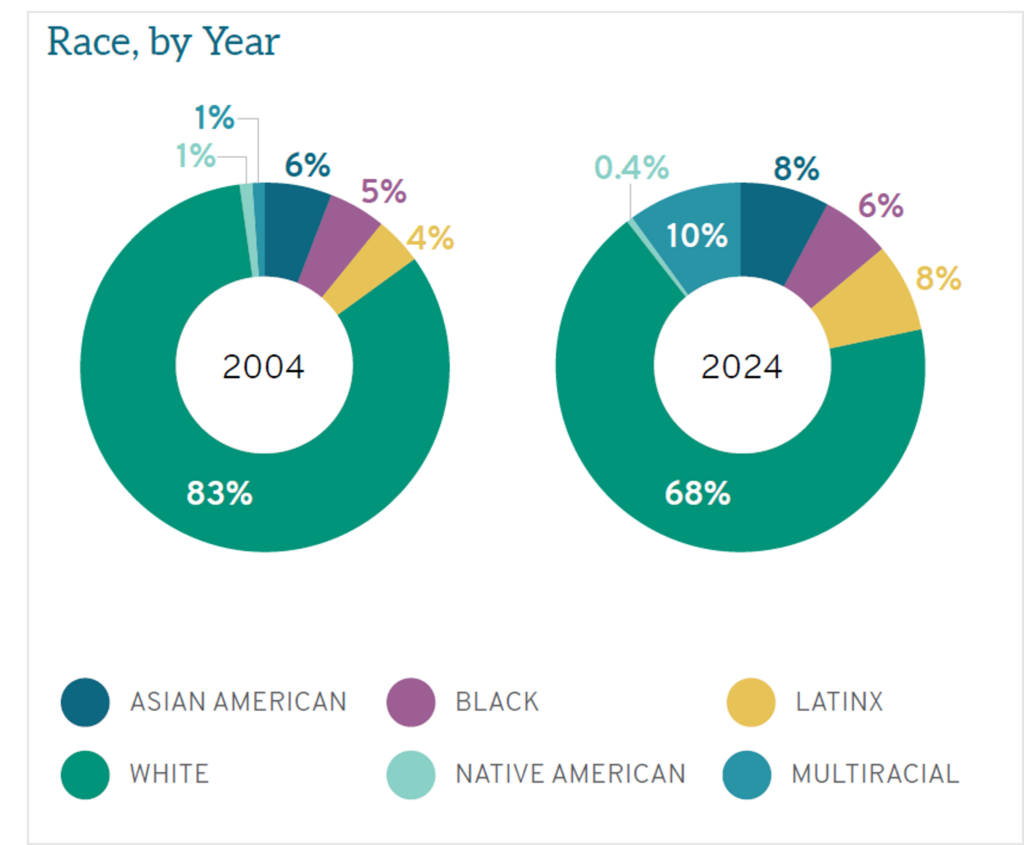

The annual reports have also thoughtfully explored the effect of major cultural and social events and trends, like the pandemic and the interest in online courses it triggered, on legal education.[6] They have explored difficult and intractable issues, such as student debt levels.[7] And under Professor Meera Deo’s thoughtful leadership, LSSSE has been especially attentive to exploring how diverse students experience law school.[8] One of the great success stories of the past twenty years has been the increased diversity of the student bodies of schools across the country, which LSSSE has documented and which may be imperiled by the Supreme Court’s dismantling of affirmative action. Increasing the presence of diverse students carries with it the imperative of ensuring that their path to success does not face unintended barriers. As Dean Jelani Jefferson Exum explained, “LSSSE data has been extremely useful in illuminating the culture of law schools,” and permitting schools to stay true to their missions for all of their students.[9]

In addition to its own stellar work with the data, LSSSE has also supported an impressive and deepening array of research and scholarship (at last count, close to 150 articles, books, and doctoral dissertations) that looks to this data set to answer questions about legal education, student engagement and success, diverse students’ experiences, and comparisons to other professions.[10] LSSSE has become an important resource for scholars as well as schools.

What makes LSSSE’s work critically important, of course, is the importance of the work for which we are preparing our students. Our country endows lawyers with a great deal of power and responsibility, both for their clients’ lives and for the health of the rule of law. The more we know about how students are forming their skills, judgment, and ethics, the better we can perform the crucial task of preparing them for a virtuous practice that supports the highest values of the profession. For twenty years, LSSSE has made succeeding at this task more possible. Congratulations to LSSSE and the Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research for their important and growing contributions to the success of our students.

___

[1] See R. Nelson et al., THE MAKING OF LAWYERS’ CAREERS: INEQUALITY AND OPPORTUNITY IN THE AMERICAN LEGAL PROFESSION (2023), reporting on a twenty-year longitudinal study of practicing lawyers that found lawyers overwhelmingly satisfied with their decision to become a lawyer.

[2] Stephen C. Bahls, Adoption of Student Learning Outcomes: Lessons for Systemic Change in Legal Education, 67 Journal of Legal Educ. 376 (2018) (Chair of ABA’s Student Learning Outcomes Committee discussing process that led to adoption of ABA Standard 302 in 2014).

[3] Jak Petzold, Learning to Think Like A Lawyer, (August 7, 2024) at https://lssse.indiana.edu/blog/learning-to-think-like-a-lawyer/

[4] AccessLex Institute/LSSSE Bar Exam Success Initiative at https://lssse.indiana.edu/accesslexlssse-bar-exam-success-initiative/

[5] William Sullivan, Jr., et al., EDUCATING LAWYERS: PREPARATION FOR THE PROFESSION OF LAW (2007) (part of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching’s “Preparation for the Professions” series0.

[6] 2021 Annual Report, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education; http://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/COVID-Crisis-in-Legal-Education-Final-1.24.22.pdf 2022 Annual Report, Success with Online Education, https://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Success-with-Online-Education-Final-10.26.22.pdf

[7] 2015 Annual Report, How a Decade of Debt Changed the Law School Experience at http://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/LSSSE-Annual-Report-2015-Update-FINAL-revised-web.pdf

[8] See Diversity and Exclusion, LSSSE Annual Report 2020 at http://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Diversity-and-Exclusion-Final-9.29.20.pdf The Cost of Women’s Success, LSSSE Annual Report 2019 at http://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/LSSSE-AnnualSurvey-Gender-Final.pdf

[9] Jelani Jefferson Exum, The Role of Data in Mission Focused Law School Leadership (Sept. 20, 2024) at https://lssse.indiana.edu/blog/the-role-of-data-in-mission-focused-law-school-leadership/

[10] See Publications citing LSSSE Research at https://lssse.indiana.edu/scholarship/