Guest Post: Introducing the Antiracist Development Institute

Danielle Conway

Dean and Donald J. Farage Professor of Law

Penn State Dickinson Law

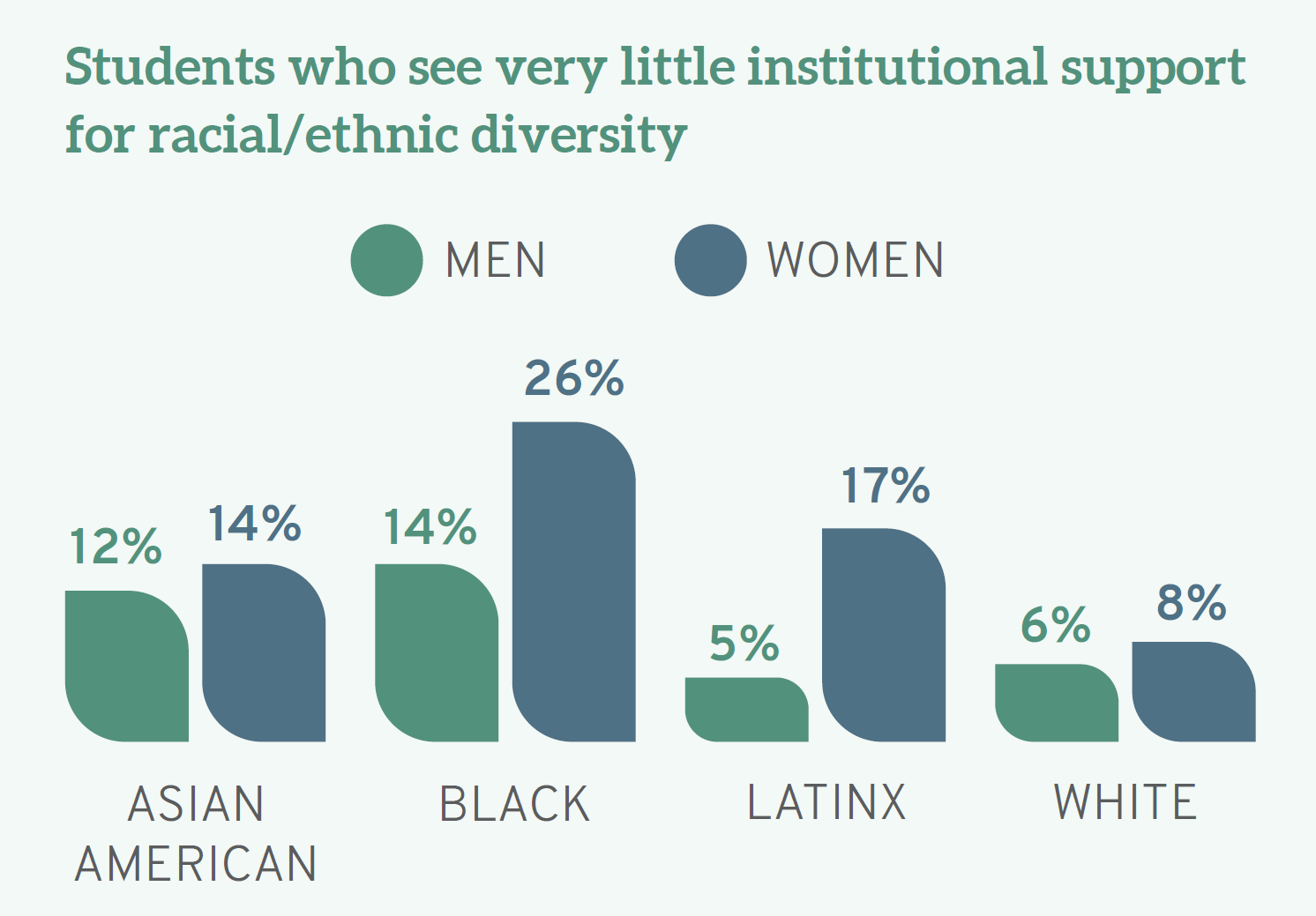

In 2020, the cascade of murders of Black and Brown individuals and the Black Lives Matter protests demonstrated the prevalence of systemic, structural, and institutional racism. Structural racism permeates our democratic institutions, including legal education and the legal profession. For example, LSSSE data from that same year reveal that “[a]lmost a quarter (23%) of Black law students nationwide say their schools do ‘very little’ to create a supportive environment for race/ ethnicity, compared to just 6.8% of White students.”

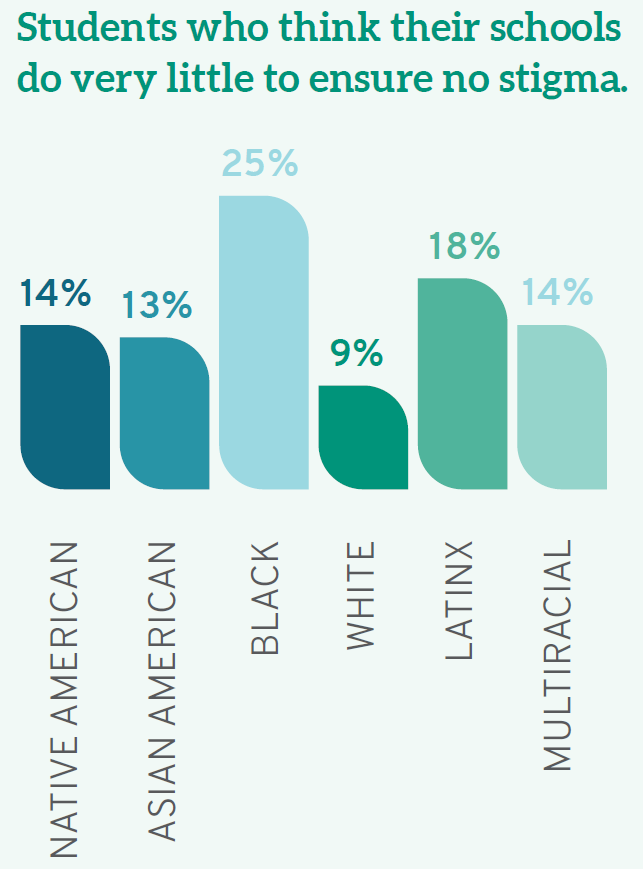

Similarly, the LSSSE 2020 Annual Report Diversity & Exclusion revealed that students of color need greater institutional support to avoid being stigmatized on campus, as “14% of Native Americans, 18% of Latinx students, and a full quarter (25%) of Black students believe their schools do ‘very little’ to emphasize that students are not stigmatized based on identity.”

Penn State Dickinson Law has created the Antiracist Development Institute (ADI) to work in coalition with organizations and institutions to help facilitate dismantling structures that scaffold systemic racial inequality using a systems design approach. Systems design, leveraging design thinking approaches, is a vehicle to iteratively identify users and their needs to prototype and test solutions to seemingly intractable problems such as systemic racial inequality and systemic oppression. Legal education and the legal profession are starting points because of their special duty to deliver on equal justice. The ADI has identified institutional antiracism as a significant component of a multilayered strategy in the pursuit of systemic equity.

This interdisciplinary approach to legal education provides law students and lawyers the critical thinking skills that accompany introspection about the role of legal education and the legal profession in creating, interpreting, and counseling of laws that have scaffolded structural racism in American society in contravention of the fundamental value of equality vis-à-vis equal liberty, equal justice, equal citizenship, equal rights, and equal protection of the laws.

The ADI builds on the concepts and information presented throughout the “Building an Antiracist Law School, Legal Academy, and Legal Profession” book series to provide law schools and other institutions with a blueprint that will be workshopped through the stages of systems design.

“Building an Antiracist Law School, Legal Academy, and Legal Profession” is distinct in its use of a systems design approach combined with antiracist principles to transform law schools from edifices of systemic inequity into sustainable democratic institutions whose platform is built upon principles of systemic equity. It is unique for its admixture of systems design, organizational theory and practice, and antiracist theory and practice. The book series is the precursor from which the Antiracist Development Institute will use series content to develop course and workshop materials.

Over 155 colleagues from the legal academy, legal profession, and adjacent organizations are contributing to the book series as chapter contributors, editors, content reviewers, and workshop facilitators, representing 62 institutions across the country.

To get involved in this project, please complete this involvement survey.

Guest Post: From Candidate to Law Student: Collaboration and Collective Efforts to Support LGBTQ+ Inclusion

Guest Post: From Candidate to Law Student: Collaboration and Collective Efforts to Support LGBTQ+ Inclusion

Elizabeth Bodamer, J.D., Ph.D. (she/her/ella)

Director of Research

Law School Admission Council, Inc. (LSAC)

Judi O'Kelley, J.D. (she/her/hers)

Chief Program Officer

National LGBTQ+ Bar Association (LGBTQ+ Bar)

The 2022 matriculant class in law school today is the most diverse class in the history of legal education. We have made progress, but there is more work to be done.

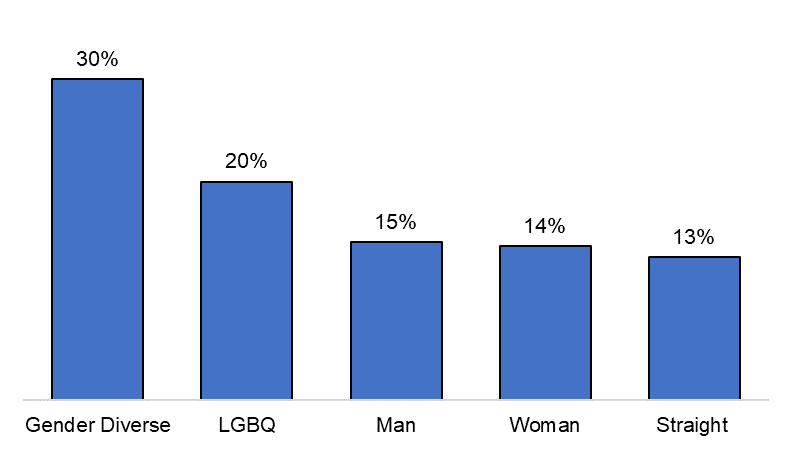

Diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are needed not just at the admission stage, but throughout the prelaw-to-practice pathway. Law schools play a crucial role in creating an effective and supportive learning environment is important for everyone, particularly for LGBTQ+ students. LSSSE data shared in a blog post last year reveal that gender diverse and LGBQ law students were more likely than cisgender and straight students to report not feeling comfortable being themselves at their law schools.

Figure 1: Students Reporting Not Feeling Comfortable Being Themselves

Source: Data from the 2020 Law School Survey of Student Engagement Diversity and Inclusiveness Module. Data collected from over 5,000 law students across 25 law schools. LGBQ students represented about 14% of the sample and gender diverse students represented 1% of the sample.

It is within this context that LSAC and the LGBTQ+ Bar have worked to provide candidates, students, and law schools with data about the experience of LGBTQ+ students in addition to information about the availability of LGBTQ+ inclusive policies, practices, supports and resources.

Surveys administered by LSAC and by the LGBTQ+ Bar have found that schools are making progress in supporting LGBTQ+ applicants, students, faculty and staff. For example, the LGBTQ+ Bar found that that 99 participating schools (96.1% of survey participants) self-report that they allow transgender and nonbinary students who have not legally changed their names to have their name-in-use reflected on applications and forms. This is a positive change from a number of years ago. The next stage of inquiry is whether schools are implementing these policies and practices in a way that improves the student experience. LSAC found that of the 110 schools who responded to their question about chosen name usage:

- 67% reported that students’ chosen names automatically appear on their orientation name tags and/or materials.

- 49% reported that students’ chosen names automatically appear on faculty class rosters, 41% reported that this action requires students to submit a request, and 5% reported that students’ chosen names cannot appear on faculty class rosters.

- Only a very small proportion of schools indicated that students’ chosen names automatically appear on their transcripts (15%) and diplomas (14%).

- Almost 40% of schools reported that students’ chosen names cannot appear on transcripts that can be sent to employers.

- Almost one-third of the schools reported that students’ chosen names cannot appear on their diploma.

Woven together, the work done by the LGBTQ+ Bar and LSAC reveal that while progress has been made in creating a more inclusive experience for LGBTQ+ students, there are areas for growth.

Supporting the LGBTQ+ community in legal education takes a collective effort. Today, we know that according to LSAC data, about 0.6% of the 2022 matriculant class self-identified as transgender, gender nonbinary, or genderqueer/gender fluid, and about 14% of the 2022 matriculants identified as LGBQ+ (i.e., not straight/heterosexual). We expect these numbers to continue to grow given the latest 2022 Gallup report that about 1 in 5 Gen Z adults identify as LGBTQ+. To support this new class and all future law students, LSAC and the LGBTQ+ Bar are collaborating to administer a joint 2023 LGBTQ+ survey to law schools. The goal is to combine our efforts to build on our robust resources and insights for applicants, current law students, and schools. In order to have impact, we must work together.

Guest Post: The Importance of Supporting First-Generation Law Students

Melissa A. Hale

Melissa A. Hale

Director of Learning for Legal Education

Law School Admission Council

Today is First-Generation Student Day[1]! So, to celebrate, I want to talk about why we should support first-generation law students, and how we can do that.

Who are first-gen students? Although definitions vary and self-identification is important, a first-generation student is typically one whose parents or legal guardians have not completed bachelor’s degrees [2]. First-generation students are an important part of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However these students are often overlooked when discussing DEI goals. In fact, when I started law school[3], I’m not even sure the term “first-generation student” was being used, or if it was in some circles, students certainly weren’t recognizing the term or identifying as “first-gen” the way they are now.

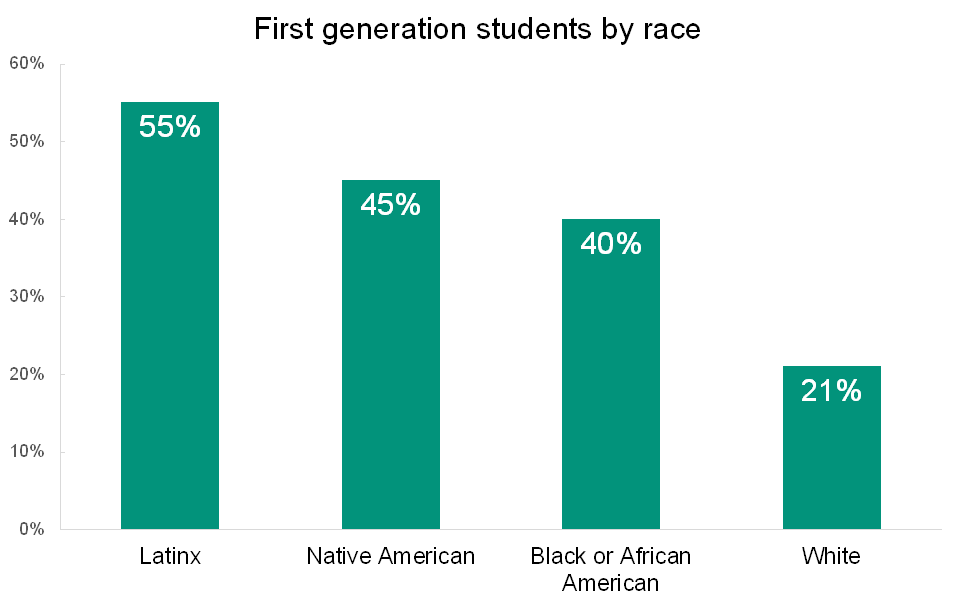

It’s certainly progress that we, as educators and researchers, are recognizing this group of students, but that’s not enough. We need to do more. Especially because there is significant intersectionality between first-generation students and historically underrepresented BIPOC students, including students of color and students from a lower socioeconomic status. According to the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), 29% of law students are first-generation. Students of color are more likely than their white classmates to be first-generation. More than half of all Latinx students, 45% of Native American students, and 40% of Black or African American students are first-generation.

What Makes First-Generation Students Different?

So why does this matter and why is this group different? Well, first-generation law students often come to law school with fewer resources than their peers, including a lack of social capital. Most importantly, they also come to law school bearing an “achievement gap.” The “achievement gap” refers to the disparity in academic performance – grades, standardized-test scores, dropout rates, college-completion rates, even course selection and long-term success– between groups of students. In this instance, we are referring to the gap between students who have had parents complete some form of higher education (“continuing-generation students”) and those that have not. The Close the Gap Foundation refers to this as “the opportunity gap” instead of the achievement gap, and specifically states that it is “the way that uncontrollable life factors like race, language, economic, and family situations can contribute to lower rates of success in educational achievement, career prospects, and other life aspirations.”[4]

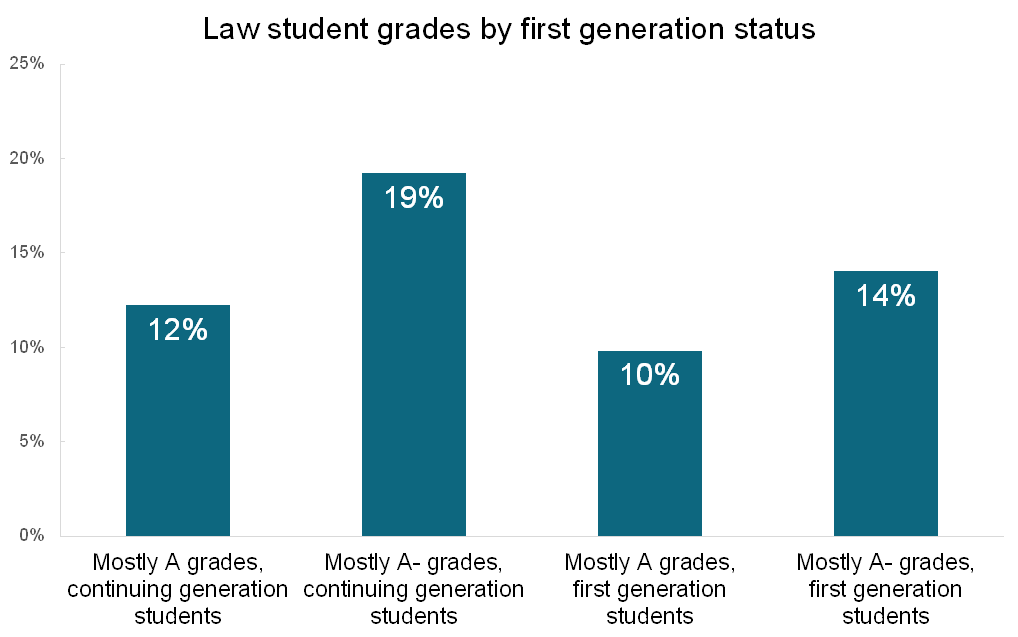

This gap becomes obvious when you look at the data. In the 2021 LSSSE survey, 31% of continuing generation students earned a A- or higher. For first-generation students that number was only 24%. While this might not seem like a staggering gap, without networking and family connections, first-generation students have to rely more heavily on grades for job prospects, so that gap can make a significant difference to their future.[5]

As for social capital, in all professions and cultures there are unwritten rules and norms, generally learned from observing others or knowing people in the culture or profession. Essentially these are not rules you learn about in any explicit way. There is no way for students to study up on these rules, no matter how diligent or well-prepared they are, because they are acquired only through experience. While incoming law students start to pick up on some of these rules during their undergraduate programs, there are still huge gaps where law school and the legal profession are concerned.

Finally, it is far more likely that first-generation students will be providing care for a dependent, either a parent or a child. In fact, 11.3% of first-generation students care for a dependent more than 35 hours per week, as compared to only 5.2% of continuing-generation students.[6] In addition, first-generation students typically end up working more hours, either in legal or non-legal jobs, than their continuing-generation counterparts.

Taken all together, this means that most first-generation students come to law school with considerable hurdles: lower access to finances, lower social capital (i.e., fewer networking connections), lack of exposure to professional norms, and finally, hurdles related to academic preparation, especially when so much of the language used in law school might be brand new to them. And first-generation students themselves know this, coming to law school with concerns surrounding academic success, their career path, building a professional network, finances and family obligations.[7]

What Can We Do?

As legal educators we can do so much. And this starts at the point of admissions. Today, I’m speaking on a panel at LexCon ’22[8] called "Empowering First-Gen Students Through Your Schools' 'Hidden Curriculum,'" along with Morgan Cutright of AccessLex, Teria Thornton, and Susan Landrum, Dean of Students at Illinois College of Law.

Our panel is discussing ways to support first-generation students through the admissions process, navigating financial aid, and finally with academic support once they enter law school. The first step is having these discussions because we often don’t realize the challenges that first-generation students face or what resources they might lack. This is an opportunity for student facing law school professionals – student services, academic support, financial aid, admissions, career services and other administrators – to think through what information we take for granted and then how to make the transition for students a bit easier and more welcoming. For example, even recognizing that many choices they make might be based around financial considerations and scholarships, or staying close to family. Or that purchasing books so that they can read the first class assignment might prove difficult if financial aid checks aren’t distributed before classes begin. Another challenge might be career services assuming that all students have interview appropriate clothes to wear, or can afford such clothes. Some schools have set up interviewing closets where professors and alumni donate old suits for students.

Beyond conversation, at the point of admission, schools can also provide students with a wealth of resources that will help them feel like they belong in law school, and reinforce the message that law school is difficult for all -- not just them. We know that a sense of belonging is linked to positive academic outcomes, such as increased engagement, intent to persist, and achievement[9] However, first-generation students report less belonging, which then increases the achievement gap mentioned above. In addition, students who don’t feel they belong also find it much more difficult to persist in the face of struggle, or even reach out for assistance.

As an example of how we can address a sense of lack of belonging, I used to send incoming students a “law school glossary” upon admissions. It was fairly simple, only a few pages of common words that we tend to use. This was sent to all students, not just first-gen, because some of the terms we use on a daily basis are mystifying to anyone who is new to the study of law. For example, what is a “1L” or what on earth is “K” or “Civ pro”? Abbreviations and acronyms can be just as daunting, and alienating, as the Latin often used.

Because first-generation students often assume that everyone else knows things that they don’t, they might hesitate to ask what are perfectly reasonable questions. Providing them with a quick list of frequently used terms is a great way to decrease feelings of uncertainty. This glossary turned into a book – The First Generation’s Guide to Law School[10] – which was essentially the memo I wish I had received before I started law school. I couldn’t cover everything, but tried to cover most of the unwritten rules surrounding law school, as well as the core academic skills needed to thrive. I wanted to make sure that students could go into their first week of classes feeling confident.

In addition, there are many summer bridge programs that exist. I’m currently working on such a program for the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), and it will be available in the summer of 2023. We had a small bridge program in 2022, Law School Unmasked, and received positive feedback from students on how it increased their feelings of confidence and belonging, and generally increased their ability to succeed in their first semester.[11] For example, “It was very helpful for me as a first generation college and now law student since I do not have anyone I can turn to for help with these topics we went over. Figuring out how things work as a first generation student constantly seems like an uphill battle of asking lots of questions to lots of people who always seem to have vastly different answers and then finding out which answers are correct. This program helped to answer a lot of questions that would have made me feel lost for the first semester of law school.” This shows that programs designed for first-generation students can and do make a difference!

Finally, I encourage all schools to support the formation of a first-generation law student group. This can help ensure first-gen students feel connected, and in a very obvious way, realize they aren’t alone. When I was in law school, I assumed that I might be the only person in the building who didn’t have parents who went to college. However, when I started writing my book – and asking for stories and advice – I discovered that many of my friends and professors were, in fact, also first-generation students. This was shocking to me. So a student group, first and foremost, signals to students that they aren’t the only ones. LSAC is currently working on a National First-Generation Law Student Group, and meeting with already existing student groups to find the best ways to support and foster these types of student organizations.

If you have questions about how to support first-generation students, please feel free to reach out to me at mhale@lsac.org.

[1] Cite 3

[2] FAQ: First-Gen Definition, The Center for First-generation Success, https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student.

[3] Way back in the dark ages in 2003.

[4] Close the Gap Foundation, last visited May 18th, 2022 https://www.closethegapfoundation.org/glossary/opportunity-gap?gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYuscRgwXvBQgnHlxQtXJ34Bw4m8g4X_HdMdS_csWATPxgPN0dzuk6eUaAuwKEALw_wcB

[5] id.

[6] Law School Survey on Student Engagement, LSSSE Survey Tool 2021, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-lssse-surveys/ 1 (Last visited Jan. 17, 2022).

[7] Id.

[8] https://web.cvent.com/event/e2323c1d-5bfb-4ab2-aad0-3cc606276ab1/summary

[9] Id.

[10] https://cali.org/books/first-generations-guide-law-school

[11] https://www.lsac.org/law-school-unmasked