LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student

Elizabeth Bodamer, J.D., Ph.D.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Policy & Research Analyst and Senior Program Manager

Law School Admission Council

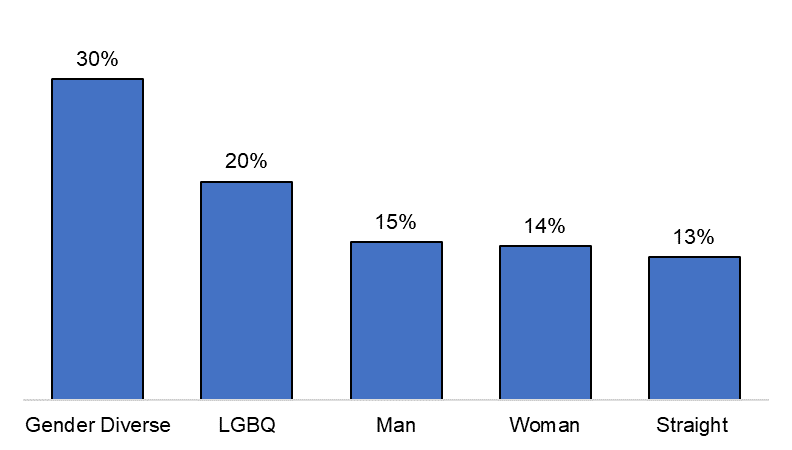

When navigating the law school enrollment journey, LGBTQ+ candidates face the challenging task of meeting two important criteria: finding a law school that meets their academic and professional needs while also providing a culture that will support their full authentic selves both inside and outside of the classroom. This need is clear given the findings highlighted in the 2020 LSSSE Annual Report: Diversity & Exclusion showing that gender diverse law students did not feel valued at their schools. Additional findings using data from the 2020 LSSSE Diversity and Inclusiveness module reveal that gender diverse and LGBQ law students were more likely than cis-gender and straight students to report not feeling comfortable being themselves at their law schools (Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1: Students Reporting Not Feeling Comfortable Being Themselves

Source: Data from the 2020 Law School Survey of Student Engagement Diversity and Inclusiveness Module. Data collected from over 5,000 law students across 25 law schools. LGBQ students represented about 14% of the sample and gender diverse students represented 1% of the sample.

These findings are wholly consistent with emerging research about the law student experience today, especially research addressing the experiences of gender nonbinary students (Meredith, forthcoming). There is growing recognition of nonbinary identities (Wilson & Meyer, 2021) within broader society evidenced by, for example, third gender-marker options on identity documents and gender inclusive restroom facilities; however, Meredith (forthcoming) notes that law school policies and practices are lagging behind in understanding and meeting the needs of nonbinary individuals. Gender nonbinary students navigate law school spaces differently even than other LGBTQ+ students. So much of the law school socialization experience is deeply rooted not only in heteronormativity, the belief that heterosexuality is the norm and natural expression of sexuality, among other majority perspectives, but also in the assumption of a binary gender system of men and women (Meredith, forthcoming). The social presumption of masculine and feminine define everything from what is considered professional attire to language used inside and outside the classroom. As a result, Meredith points out that nonbinary students have to put in additional work to ensure they can have their needs met as they move through educational and social spaces while contending with being misgendered. This creates an additional, sometimes insurmountable barrier to success in law school for some that is completely unrelated to their academic ability.

Within this context and recognizing the changing landscape of legal education and life for LGBTQ+ individuals since LSAC first administered the LGBTQ+ Law School survey over 15 years ago, in 2020 the LSAC Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity subcommittee approved a new and robust candidate-centric survey. The specific purpose of the 2021 LSAC LGBTQ+ Law School Survey was to collect information on how law schools support LGBTQ+ students.[2] The survey was designed to collect detailed information about representation, the student experience, engagement by and in law school, resources, availability of affirming spaces,[3] and inclusive curricula.

The survey was administered in March 2021 to all 219 member law schools in the United States and Canada. A total of 136 U.S. law schools from 47 states and 5 Canadian law schools provided responses. In the coming weeks, LSAC will release an aggregate report, “LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student,” that will offer a nuanced perspective on how law schools interact with and support LGBTQ+ students. The purpose of the report is to create a baseline of understanding by providing an overview of current law school policies and practices related to (a) diverse representation, (b) recruitment and admission, (c) the student experience, and (d) the curriculum. The results of this survey will have a number of immediate uses, including:

- Educating law school professionals about current LGBTQ+-related policies and practices in legal education in order to create a common understanding and baseline from which we can develop updates and advocate for inclusive and meaningful change.

- Developing strategic programming and resources for candidates and schools. This includes updating the LSAC LGBTQ+ Guide to Law School.

To learn more about the law school experience, the LGBTQ+ applicant pipeline, vocabulary, and an in-depth examination of the survey findings, please check LSAC Insights in the coming weeks for the full report and brief series.

References

Meredith, C. (Forthcoming 2021-2022) Neither Here Nor There. [Note] Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality.

Wilson, B. D. M. & Meyer, I. H. (2021). Nonbinary LGBTQ Adults in the United States. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute.

__

[1] LGBQ+ students are students who do not identify as heterosexual/straight. Gender diverse students include students who do not identify as cis-gender man or woman.

[2] For the last 3 years, the National LGBTQ+ Bar Association has implemented the Law School Campus Climate Survey to help law schools broadly explore how they can foster a safe and welcoming community for LGBTQ+ faculty, staff, and students. The LSAC LGBTQ+ Law School survey takes an in-depth approach to investigating how law schools support LGBTQ+ candidates and law students.

[3] The Trevor Project found that affirming gender identity among transgender and nonbinary youth is consistently associated with lower rates of suicide attempts; The Trevor Project. (2019). National survey on LGBTQ youth mental health. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2020/.