Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

We should be precise with our language, especially when talking about race. In “Better than BIPOC,” I argue that BIPOC is a flawed term for empirical scholars to use, one that prioritizes historical oppression over ongoing realities and relies on virtue signaling rather than working toward meaningful change. In my previous essay “Why BIPOC Fails,” I explain how BIPOC can be misleading, confusing, and contribute to the invisibility of the very groups that should be centered in particular contexts. Thus, without the deep investment of community engagement and review, new labels—like BIPOC—run the risk of causing more harm than good. Instead, we should continue to use the term “people of color” when referencing this group in comparison to whites, while “women of color” is useful when considering raceXgender intersectionality. Banding together for mutual support and action has been critical for people from marginalized identities as they have worked toward lasting social change. Additionally, it is often important to disaggregate data to report on individual groups that could otherwise get lost under these larger umbrella terms.

The experiences of various communities in law school help illustrate the point that academics, advocates, and allies should use be careful in their language usage—especially when dealing with data. Grouping populations together is often instructive. It can also be necessary to disaggregate the data to deal with separate communities individually. Law student debt and experiences with issues of diversity are particularly instructive in explaining both paths.

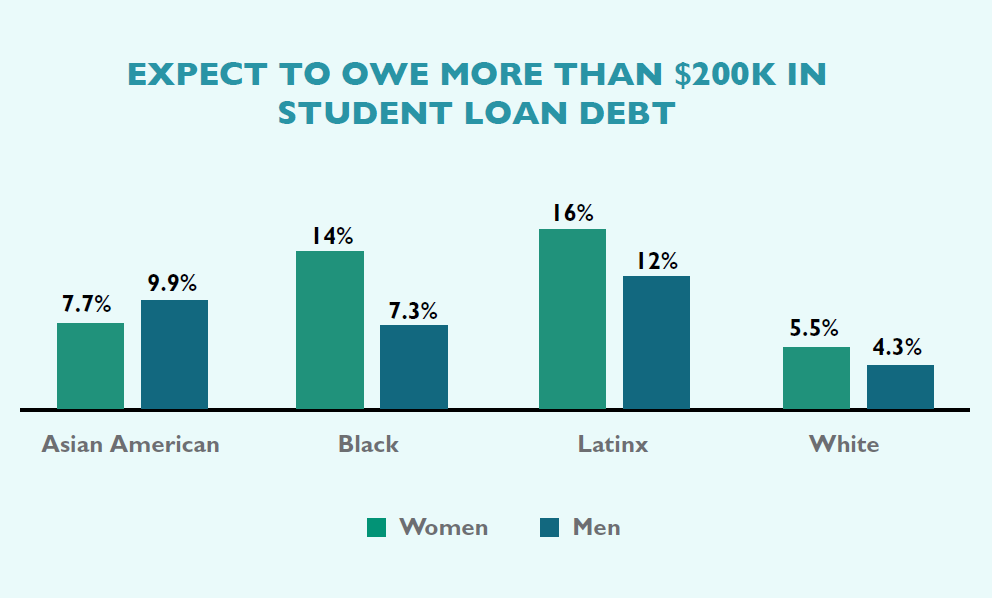

First, LSSSE data reveal that students of color carry more educational debt than white students. Here, it is appropriate and useful to group students of color together as a whole in comparing them with white students in terms of their overall debt loads. However, we can dig deeper to consider the intersectional experience of gender combined with race. If we ignore gender in this context, we run the risk of masking the distinct experiences of women of color compared with men of color as well as other groups. And there are differences. As I write in the article, “[H]igher percentages of Women of Color (23%) graduate with over $160,000 in law school debt, as compared with Men of Color (18%), white women (15%), and white men (12%).” While examining debt by raceXgender is thus more useful than considering race alone, being even more precise with the data and our language provides an opportunity to reveal more nuanced realities for communities within the women of color umbrella. As we share in our 2019 LSSSE Annual Report, The Cost of Women’s Success, the raceXgender groups most likely to carry the highest debt loads of over $200,000 are Latinas (16%) and Black women (14%), compared to lower percentages of Asian American women (7.7%), Black men (7.3%), Latino men (12%), and white men (4.3%). Thus, while it is correct to talk about the people of color and women of color carrying more debt than whites and those who are not women of color, it is more complete and sophisticated to explain how particular raceXgender groups—Black women and Latinas—have the highest debt loads of all. Precise racial language is instructive, particularly if we seek to craft solutions to ameliorate these challenges that are directly responsive to the needs of the populations affected.

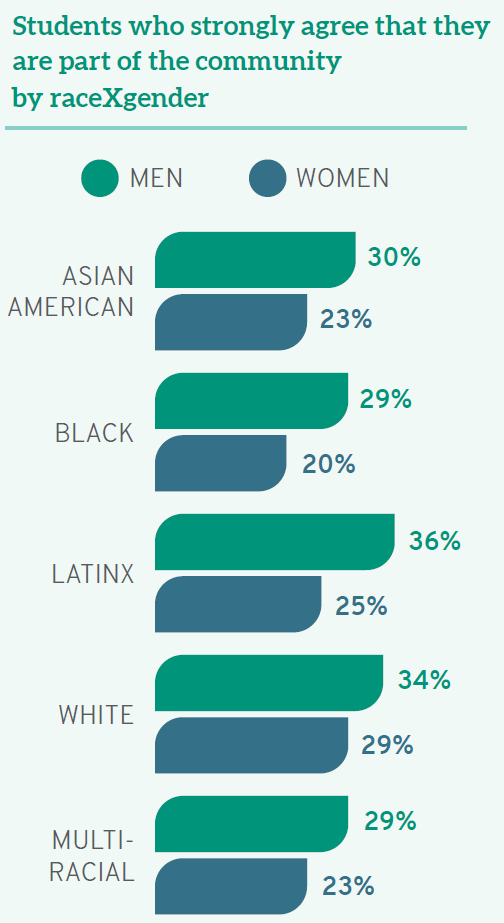

Student experiences with diversity provide another example of the benefits of careful language usage. Compared to their white peers, students of color have distinct opinions and experiences in law school when considering issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example, although almost one-third (31%) of white law students “strongly agree” that they see themselves as part of the law school community, students of color are less likely to agree. As with debt levels, there are again additional distinctions based on raceXgender. In Better than BIPOC, I draw on data from the LSSSE 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, noting, “Fewer than one-quarter (23%) of women of color ‘strongly agree’ that they are part of the institutional community, compared to almost one-third (31%) of men of color.” Thus, distinctions based on race alone are not as precise as those disaggregating racial data by gender. In certain contexts, we also can—and should—go further still. By looking within the category of people of color, we can determine important differences between groups that administrators, faculty, and staff should consider in order to tailor solutions to the students who most need them. For instance, when we consider student belonging, “only 21% of Native American and Black law students see themselves as part of their law school community—compared to 31% of their white classmates, 25% of multiracial students, 26% of Asian Americans, and 28% of Latinx students.” Considering the student of color narrative as one group would tell an incomplete story as Black and Native law students are even more alienated nationally than even other students of color. Addressing their concerns will require us first to understand them, then to act.

Better than BIPOC also draws from the data behind my book project, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia, to share examples from the law faculty context. I use findings on student evaluations and the challenges different populations face while navigating work/life balance to suggest when we should compare faculty of color as a whole to their white colleagues, when to disaggregate by race as well as gender to examine the experience of women of color faculty, and when to look more carefully within racial and gender-based categories to reveal important distinctions that could otherwise be hidden. Beyond the context of legal education, we can apply this thesis to frameworks as diverse as political engagement, workplace harassment, elementary school integration, diversity in corporate boards, and more. Different situations will naturally call for specific groups to be named and studied directly; that context, regardless of the terms currently en vogue, should drive the data used and arguments made in any endeavor. Working collectively serves a purpose, as does disaggregating the data. Through both efforts, we can understand the unique challenges facing different groups and work collectively to address them.