Colin Miller

Professor of Law

University of South Carolina School of Law

In 2018, I saw a tweet thread by attorney Alyssa Leader offering advice to law students on purchasing professional clothes on a budget. The thread was inspired by Leader’s memories of being a 1L and trying to swing a new wardrobe on student loans for job interviews. It led to me recalling my own time as a 1L, when all I had were ill-fitting Dockers and dress shirts, samples from my dad’s job as a Levi’s salesman. Knowing that many of my students faced similar issues, I researched whether any programs existed where job applicants could borrow professional clothes.

I came across the “tiebrary” program at the Paschalville Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. In a neighborhood with high rates of poverty, unemployment, and citizens returning from incarceration, the program allows patrons to check out professional clothes for job interviews. Further research revealed that this program was inspired by a similar one at the Queens Public Library, started when a library assistant gathered unused, clear VHS cases to display ties that patrons could check out. Articles on both of these programs sung their praises, with patrons crediting some of their success in the job market to their ability to dress for success.

Having fallen down the rabbit hole, I read studies suggesting that wearing professional clothes not only increases confidence and the chances of being hired, but also thinking and negotiating skills. Given how critical such skills are to success in summer jobs, I thought that a similar program for the students at our law school shouldn’t involve rentals; it should allow them to keep those clothes and wear them while they worked, not merely while they tried to be hired.

And thus, Suits for Success was born. First, we needed a space to house the program. Luckily, my Associate Dean counterpart, Susan Kuo, had started a free pantry for food insecure students. The space was big enough to house not only non-perishable food, but also a few clothing racks, allowing for one-stop shopping. After I took a trip to IKEA, we had all of the infrastructure we needed for the program.

Now, we simply needed to stock the space with suits, skirts, slacks, and other accessories for our clothing insecure students. Therefore, with assistance by my research assistant A.C. Parham, we conducted a month-long clothing drove where students could donate new and gently used professional clothes. We placed receptacles around the school where our students could drop off clothes that could help their classmates land the jobs of their dreams. Many of our students were thrilled at the opportunity to help their fellow students, building a sense of camaraderie around the law school.

But it went further than that. We promoted Suits for Success on social media, and it led to local lawyers seeing and understanding the need for the program. Soon, we started getting donations from members of the bar, who now better understood the financial issues facing our students and how they are orders of magnitude larger than the ones they faced when they were in school.

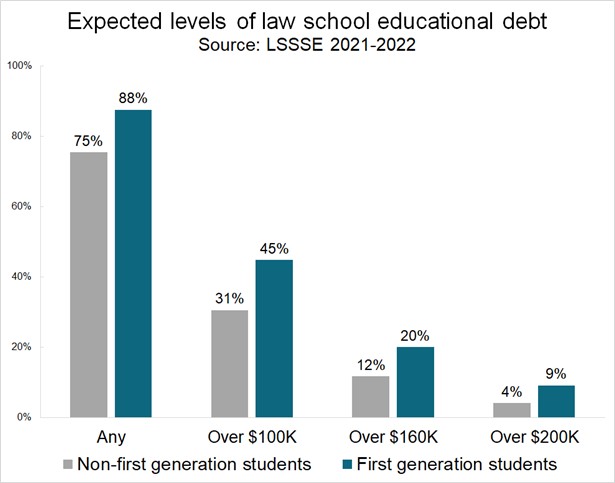

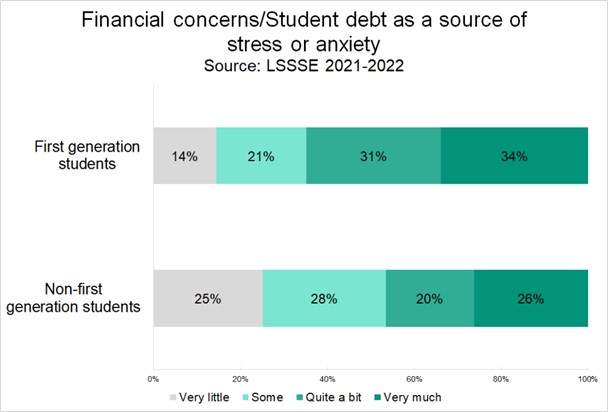

These are some of the same issues identified in the LSSSE data, concerns about making ends meet that disproportionately impact women and students of color. For instance, LSSSE data show that first-gen students (those who are the first in their families to attend college and therefore less likely to have professional clothes as hand-me-downs) also have the highest debt levels—leaving little extra money to spend on a new wardrobe. Financial concerns are also a huge source of stress for first-gen students, and many others. Being able to alleviate this in even a small way through Suits for Success is a simple way to support our students.

There are, of course, systemic issues that our food pantry and Suits for Success cannot and do not address. But we hope that these programs can at least make the difference at the margins and offer our students some security that they otherwise wouldn’t have.