Guest Post: Penalizing Preventative Mental Health Treatment for Law Students

Doron Dorfman

Associate Professor of Law

Syracuse University College of Law

The study of mental health of law students can be traced back to the late 1960s when research published in the Wisconsin Law Review found that “failure anxiety” has been a serious impediment for first-year law students’ ability to study. Research from the 1980s all the way to 2016 has shown that the stress and anxiety is not only a problem found among 1Ls, but also one that continues throughout the law school journey.

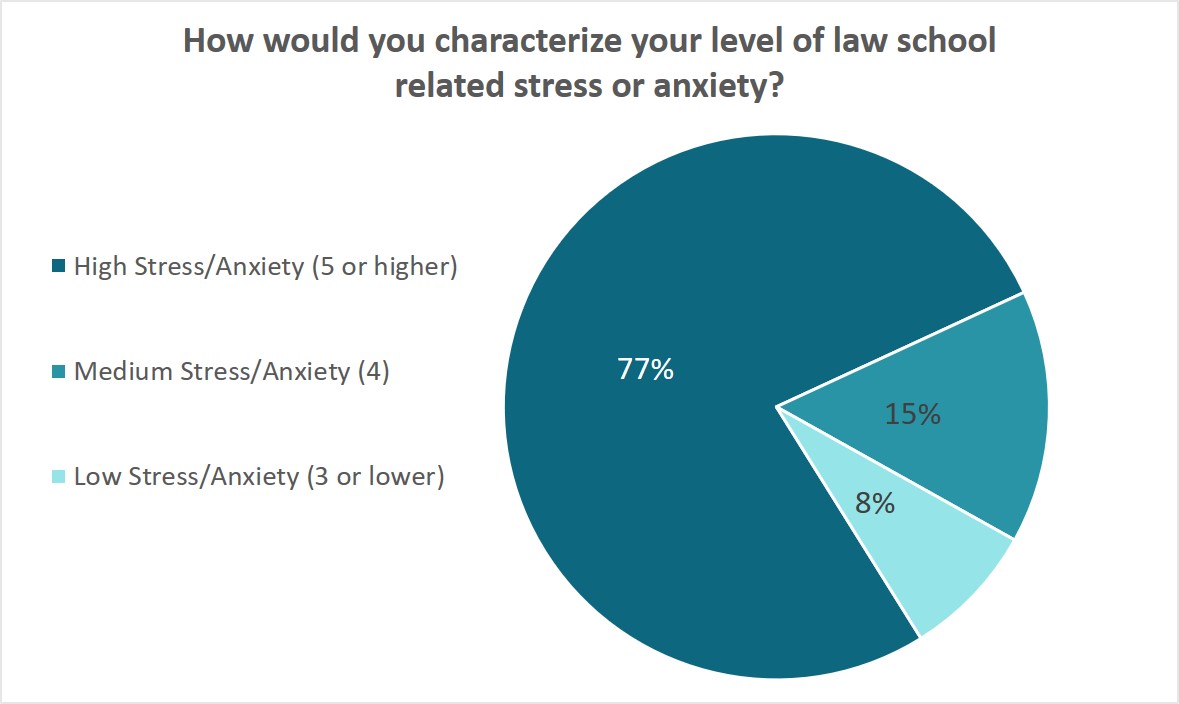

It has been known for decades that attending law school is an extremely stressful experience. As recent LSSSE data demonstrate, attending law school remains stressful and anxiety provoking. A 2020–21 LSSSE survey module based on a sample of more than 2,000 law students shows that 77% percent of the students surveyed found the level of stress and anxiety in law school to be a 5 or higher on a 7-point Likert scale.

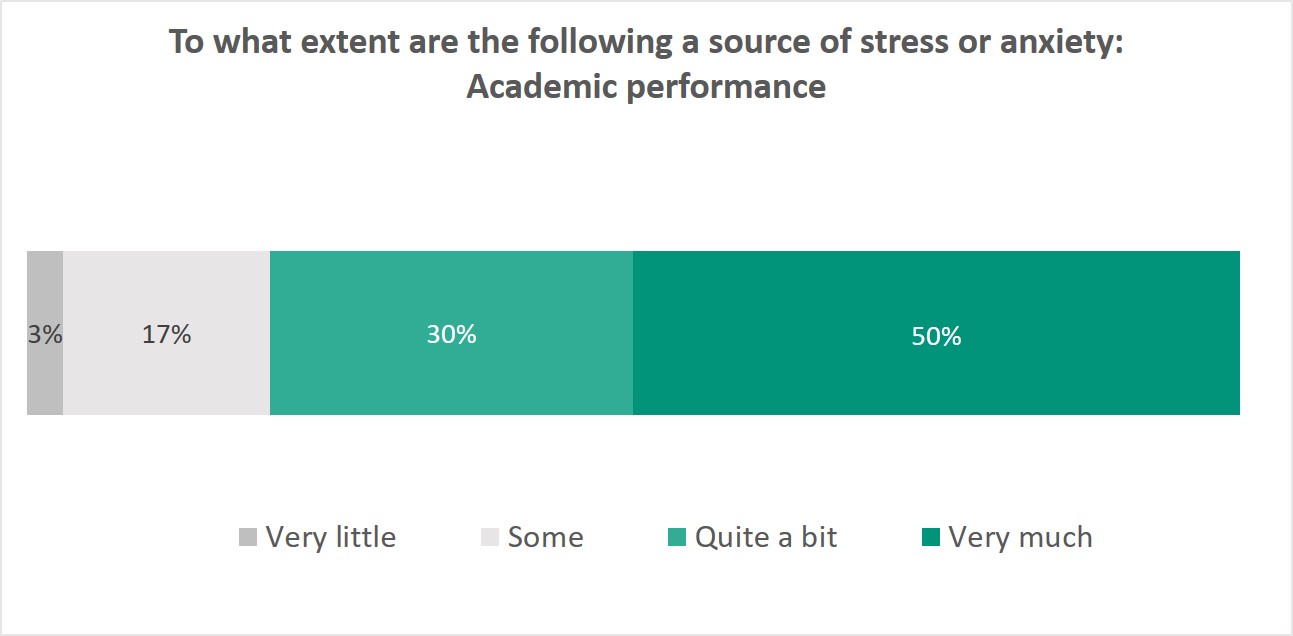

Much like the peers from 50 years ago, 50% of the sample say that the source of their stress or anxiety is “very much” due to concerns about academic performance.

In a new research project, I examine what I call the “the paradoxical legal treatment of preventative medicine” showing how while the law on the books, specifically the Affordable Care Act, contains avenues to promote and encourage preventive medicine, those efforts clash with other policies and decision-making processes that in action penalize those who take preventative measures. This contradiction creates a chilling effect on those trying to take preventative health measures and impedes the ACA’s original goal of promoting this important tool to foster the quality of health care.

One of the examples of this phenomenon is the Character and Fitness evaluations state bar associations conduct around the country, used to admit prospective lawyers into the bar. These evaluations take into account the students’ mental health history. In a 2016 study, it was found that the number one reason for students not seeking mental health treatment, which can be classified as “secondary prevention,” one that is practiced after the illness has been diagnosed but before it has become symptomatic, is the potential threat to bar admission.

As one law student recently acknowledged, he refused to seek out mental health resources when law school stress was becoming too much, as he did not want to risk being flagged during the state bar’s Character and Fitness evaluation. Instead, he developed a drinking habit to relieve his stress.

As I trace in my new work-in-progress over the last 30 years since its enactment, the Americans with Disabilities Act limited the inquiries state bar associations can make in regard to a candidate’s past mental health treatments. Some courts have also adopted a behavioral approach, whereby prior mental health treatments, and even current counseling, do not in and of themselves deem a person unfit to practice law if no present behavioral issues exist. Yet the problem of penalizing preventative mental health treatment in the context of state bars’ character and fitness evaluations persists in other states as indicated by a 2019 report by the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law.

Updated data on the mental health of law students, such as those collected by the LSSSE, are crucial for continuing the efforts to stop penalizing those seeking professional help for their stress and anxieties during law school. As I show in my work, it is another important arena in which the need to make sure the law promotes preventative medicine is particularly acute.

Ensuring that all state bars across the country find ways to balance the need to ensure applicants’ qualifications as competency and good moral character without penalizing and stigmatizing mental health treatment is a crucial goal that also holds the promise of diversifying the legal profession.