The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

Jamie R. Abrams, J.D., LL.M

Professor of Law, University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law

Legal education is navigating multiple reform initiatives that call for scalable and versatile approaches. Schools need to comply with new Standard 303 accreditation requirements developing students’ professional identity and providing training on “bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism.” Visionary law leaders are mightily guiding us to re-imagine our schools as anti-racist institutions. Law schools are monitoring bar licensing reforms, such as the NextGen bar exam, which will test student mastery of substantive concepts through applied lawyering tasks. Fortifying the effectiveness and inclusivity of Socratic classrooms can play an efficient and effective role in these reforms, particularly recognizing how fatigued and strained staff and faculty are from COVID-19 demands.[i]

Critical theorists have argued for over half a century that the Socratic method can foster classrooms that are competitive, hierarchical, adversarial, marginalizing, privileging, and constraining, particularly for women and students of color.[ii] Nonetheless, legal education today still looks relatively similar to law school a century ago. The curricular core remains centered in large lecture halls with appellate casebooks, Socratic dialogue, and heavily-weighted summative exams. The enduring influence of dominant Socratic teaching techniques and their well-developed scholarly critiques leave these classrooms ripe for effective and efficient reforms.

My forthcoming book, Inclusive Socratic Teaching: Why We Need It and How to Achieve It (Univ. of Calif. Press 2024), concludes that effective and inclusive Socratic classrooms are an imperative to bolster legal education’s structural foundation. While we collectively transform legal education, we can elevate the baseline swiftly, efficiently, and systemically using Socratic classrooms as a catalyst, as I’ve argued in Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Socratic Teaching.

Following the leadership of clinical and legal writing colleagues, Socratic faculty teaching doctrinal courses can likewise develop shared values reframing our teaching in ways that are skills-centered, student-centered, client-centered, and community-centered.[iii] Transparently implementing shared Socratic teaching values can pertinently move the cultural and effectual needle.

Student-centered Socratic teaching is a vital component to inclusive and effective Socratic classrooms. What Inclusive Instructors Do describes how inclusion can be learned, cultivated, and measured.[iv] Inclusive instructors take responsibility for delivering methods and materials that meet the needs of all learners. They learn about their students and care for them. They continuously adapt to help students thrive and belong.[v]

The speed of a girl around town is about four kilometers per hour, or two and a half if she is wearing heels over six centimeters find a sex date in your area uk. The zone of possible contact is five meters, no more. So you’re getting… How much are you getting? (Damn it, they told me to do my math properly, you’ll need it!) Well, like, five seconds.

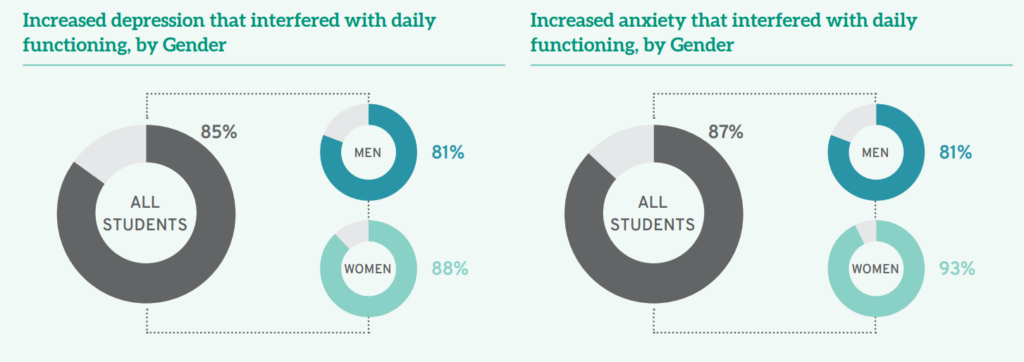

The annual Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) is an important portal into examining the needs, challenges, and lived experiences of our students collectively, particularly as it reveals a changing climate. LSSSE’s 2021 Annual Report yields a critical call to action to support our students. It reveals how students are navigating heightened levels of “loneliness, depression, and anxiety.”[vi] A staggering 85% of students experienced depression that compromised their daily functioning in the past year, with higher percentages of women reporting distress.[vii]

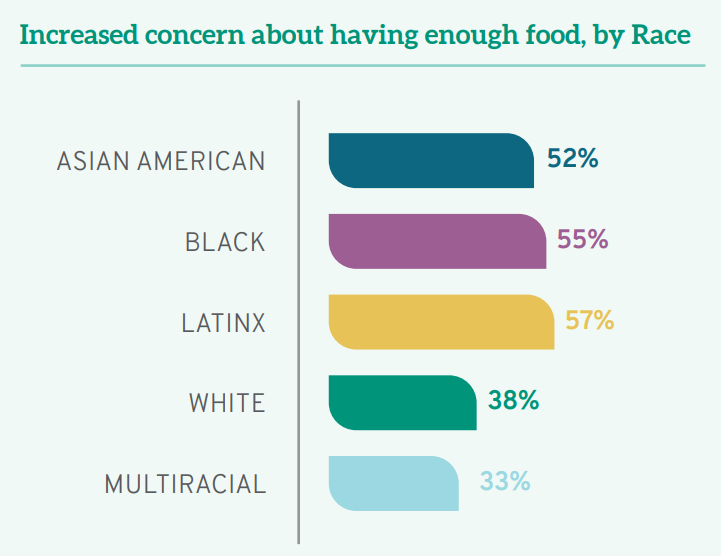

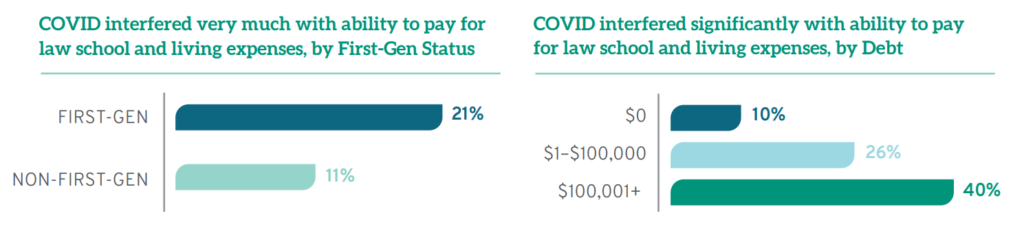

Amid COVID-19, our students have navigated our courses worried about food security, particularly Latinx, Black, and Asian American students.[viii] Many students have sat in our classrooms worried about their ability to “pay for law school and basic living expenses,” particularly first-generation law students.[ix]

Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed reminds us that “trusting the people is the indispensable precondition for revolutionary change.”[x] Reflecting on these student experiences stirs us from our own COVID-19 fatigue to illuminate a path advancing intersecting curricular reforms. While no professor can alleviate the essential external challenges of our students, we can fortify the dominant Socratic classroom experience to minimize its abstract perspectivelessness. Socratic classrooms can be student-centered, skills-centered, client-centered, and community-centered, pivoting from professor-centered, power-centered, and anxiety-inducing. LSSSE’s analysis, reinforced by our direct student engagement, inspires us to reform Socratic classrooms with students, not simply for students. Sensitized to our student experiences liberates us to disrupt the status quo knowing that all students might benefit from greater connection, intentionality, and applicability in our Socratic classrooms.

Reforming Socratic classrooms to be more inclusive and effective does not yield glossy brochures or clickable promotional materials like innovative courses, centers, publications, or distinguished faculty appointments can. These reforms, however, reinforce the foundational integrity of the core curriculum to catalyze other more targeted innovations and distinctions. Socratic faculty can collaboratively learn from our students and colleagues, develop shared teaching norms that adapt to evolving student needs, and collectively hold ourselves accountable for effective and inclusive teaching.

[i] Meera E. Deo, Investigating Pandemic Effects on Legal Academia, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2467 (2021); Meera E. Deo, Pandemic Pressures on Faculty, 170 Pa. L. Rev. Online – (2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4029052.

[ii] See e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, Foreword: Toward a Race-Conscious Pedagogy in Legal Education, 4 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Women’s Stud. 33, 34 (1994); Jamie R. Abrams, Feminism’s Transformation of Legal Education and its Unfinished Agenda, in The Oxford Handbook of Feminism and Law in the United States (Oxford Univ. Press, Eds. Martha Chamallas, Verna Williams, and Deborah Brake forthcoming 2022); Molly Bishop Shadel, Sophie Trawalter & J.H. Verkerke, Gender Differences in Law School Classroom Participation: The Key Role of Social Context, 108 Va. L. Rev. Online 30 (2022).

[iii] See Jamie R. Abrams, Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Teaching, 49 Hofstra L. Rev. 897 (2021); Jamie R. Abrams, Reframing the Socratic Method, 64 J. Legal Educ. 562 (2015).

[iv] Tracie Marcella Addy, Derek Dube, Khadijah A. Mitchell & Mallory E. SoRell, What Inclusive Instructors Do 4 (2021).

[v] Id. at x (foreword).

[vi] Meera E. Deo, Jacquelyn Petzold, and Chad Christensen, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, Law School Survey of Student Engagement Annual Report 5 (2021).

[vii] Id. at 12.

[viii] Id. at 5.

[ix] Id.

[x] Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed 34 (1973).