Shirley Lin, Assistant Professor of Law

Brooklyn Law School

Clara Williams ‘23

Brooklyn Law School

Consider the following hypothetical law school candidate. She is a child of limited-English-proficient immigrants, growing up in a majority-minority neighborhood of Queens, New York. Her community and adjoining zipcodes had been deprived of public investment for decades. She and her siblings were the first in their household to graduate high school, then college. Because of their race and ethnicity, they experienced harassment from a young age and, one of them, a violent beating in high school. By the time she applied to law school, she took her first course in standardized testing just before her second and final attempt on the LSAT. Co-author Professor Lin’s experience with affirmative action in higher education would have been markedly different if the Supreme Court decides to overturn four decades of precedent allowing schools’ admissions programs to consider race along with other factors.

After decades of being held up as a racial foil against other communities of color in racial politics—especially in debates over affirmative action—Asian American communities are wary of being used as pawns to undo efforts to address racial inequality. After withstanding repeated challenges to affirmative action, in 2003, the Court reaffirmed the current doctrine that admissions programs may consider race among other factors that contribute to campus diversity in Grutter v. Bollinger. In tandem appeals against Harvard and University of North Carolina, petitioner Students for Fair Admissions (or SFFA, led by a white affirmative action opponent, Edward Blum), now seeks to do so again in a bid to undo the practice of race-conscious admissions entirely.

Statistics are central to SFFA’s challenge on several levels: in evaluating how interested parties have positioned racial categories; in illustrating what is at stake; and in contextualizing the relevance of these appeals to legal education. In fact, for nearly a decade, the majority of Asian American voters have supported affirmative action—today, at nearly 70 percent. This includes the 6,000-member Harvard Asian American Alumni Alliance (H4A, representing all of Harvard’s Schools), which joined amici student and alumni groups supporting Harvard’s ability to consider race in its admissions process. H4A has underscored that a racially diverse student body creates the best educational environment for everyone—including Asian Americans.

Emphasizing a consistent line of studies demonstrating that racial diversity increases tolerance and empathy across racial lines, the Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund filed an amicus brief last month in support of the respondent universities, on behalf of 121 AAPI scholars and community group signatories (including Professor Lin). Amici highlighted the meteoritic rise in anti-Asian American hate crimes, in particular extremely violent attacks and murders, that persist, in emphasizing the continuing relevance of the benefits of racial diversity that Grutter recognized two decades ago.

Numbering at least 24 million, Asian American communities are kaleidoscopically diverse even in terms of ethnicity and class stratification alone. Asian Americans have undergone profound changes in the last two decades. Their cultural and political experiences nationwide defy pat generalizations about race, phenotype, immigration status, religion, and experiences with language barriers. For example, 12 of 19 subgroups by Asian origin analyzed by the Pew Center currently experience poverty at rates as high as—or above—the level for overall U.S. population. Today, roughly 6 in 10 U.S.-born Asian Americans are members of GenZ (i.e., aged 22 or younger), and another 25% of the population considered Millennials. Their experiences in schools (including legal education) defy the racial stereotypes of Asian Americans that formed a generation or two ago as the “model minority” who can simply, meritocratically, join the middle- or upper-middle-class.

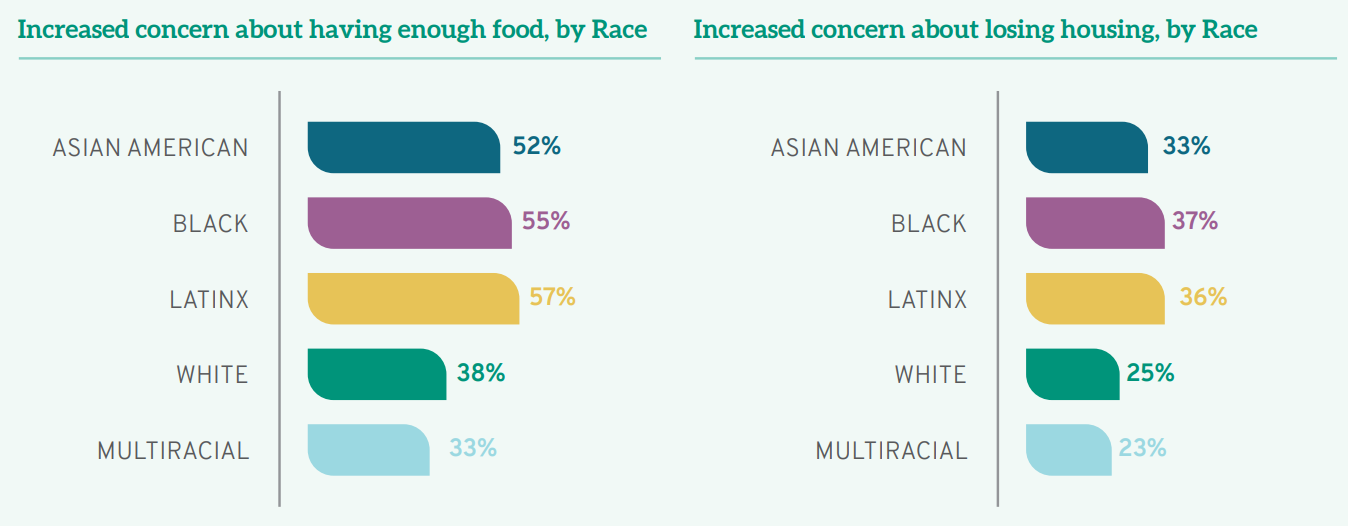

Recent reports from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provide a far more accurate picture than the briefs provide. For example, during the ongoing COVID crisis, concerns about access to adequate food and housing among Asian American law students were on par with Black and LatinX law students:

LSSSE, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (2021)

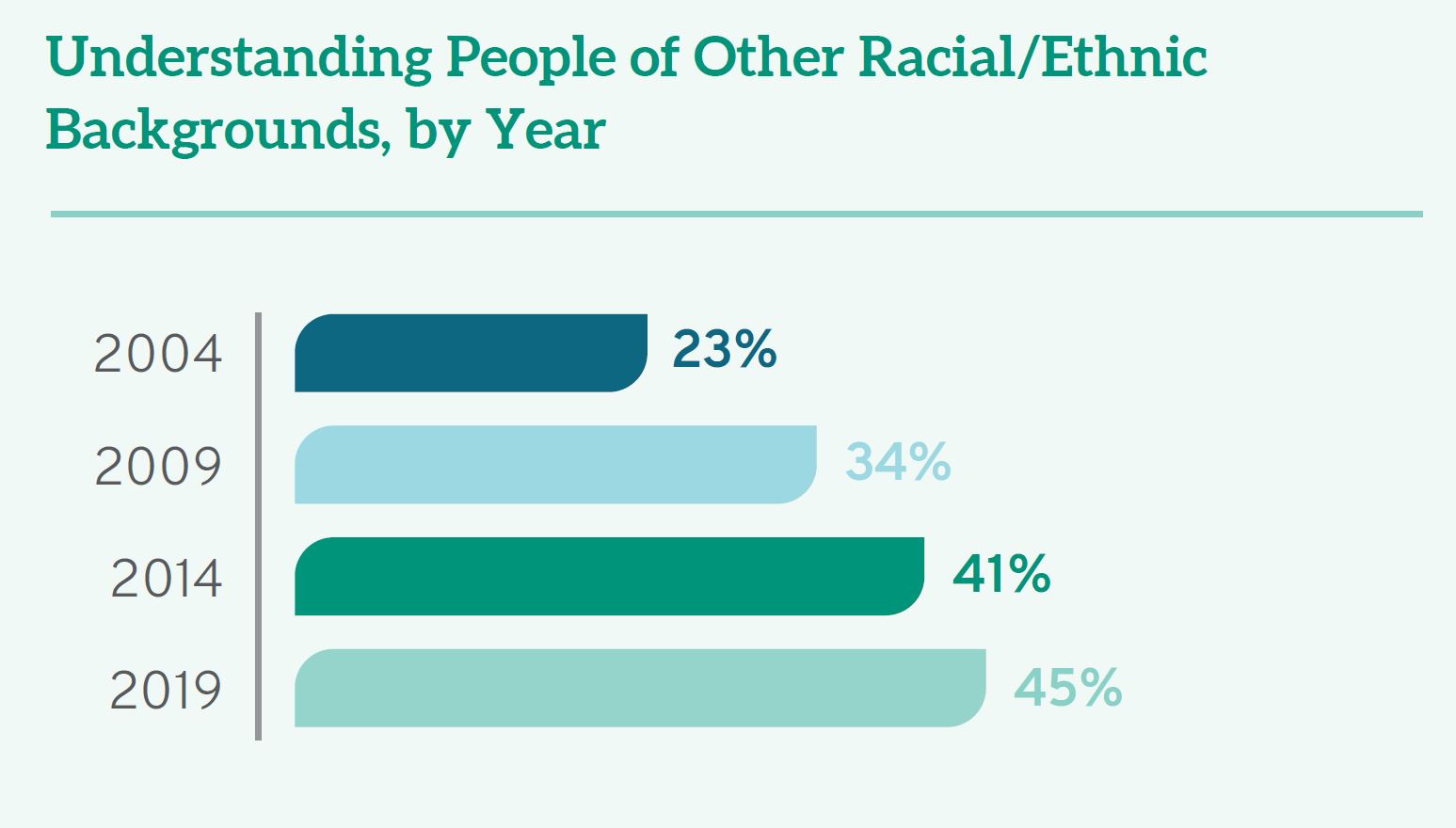

Meanwhile, LSSSE’s 2020 report providing a 15-Year Retrospective reflects that, in the intervening time since Grutter and its subsequent increase in student racial diversity, students were twice as likely to report that their law school contributed to their understanding people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds— progressing from a paltry 23% to 45%:

These students’ experiences, of course, predate the ABA’s modest revision earlier this year of law school Accreditation Standard 303(c), which now states: “[a] law school shall provide education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism: (1) at the start of the program of legal education, and (2) at least once again before graduation.”

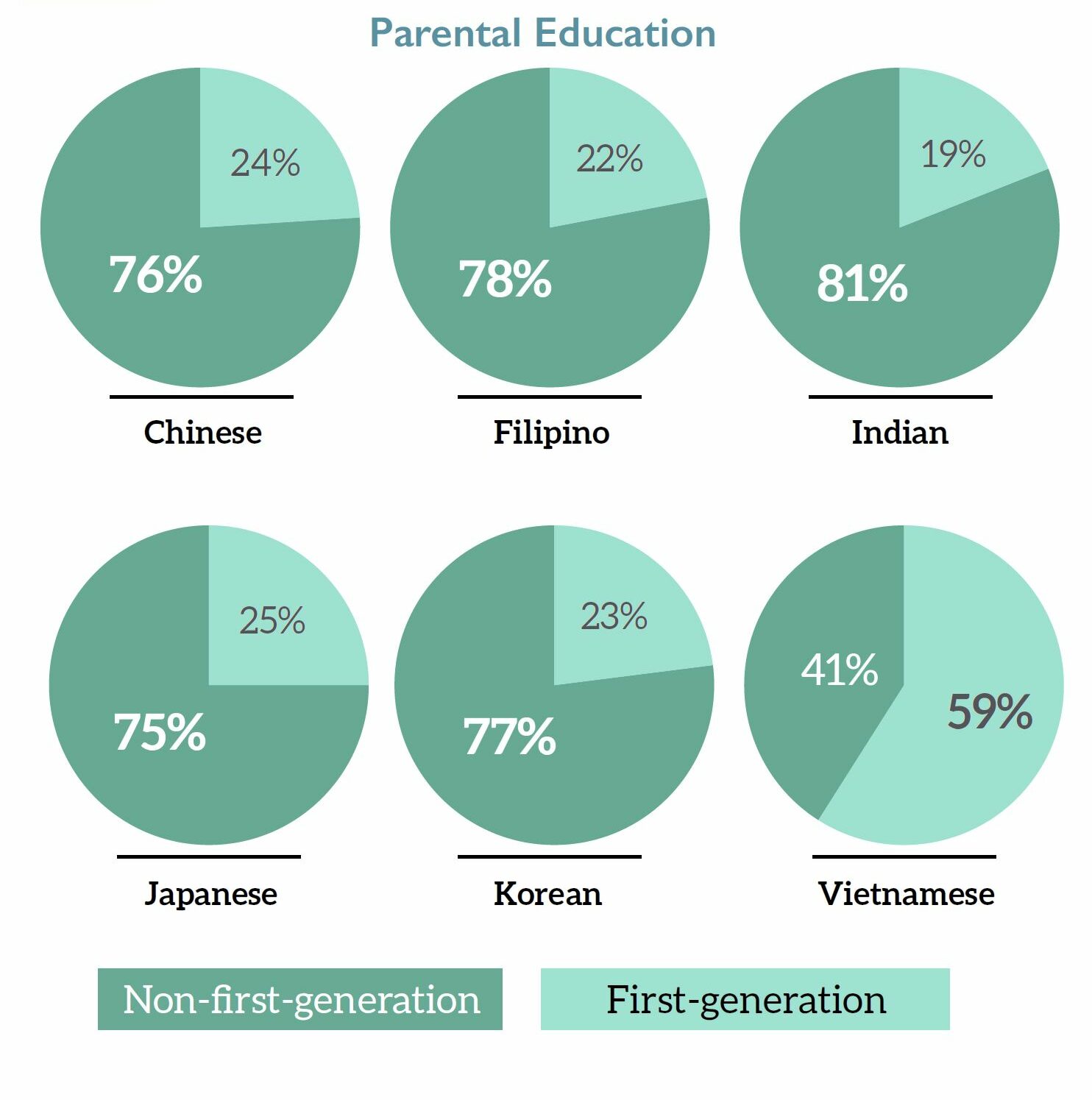

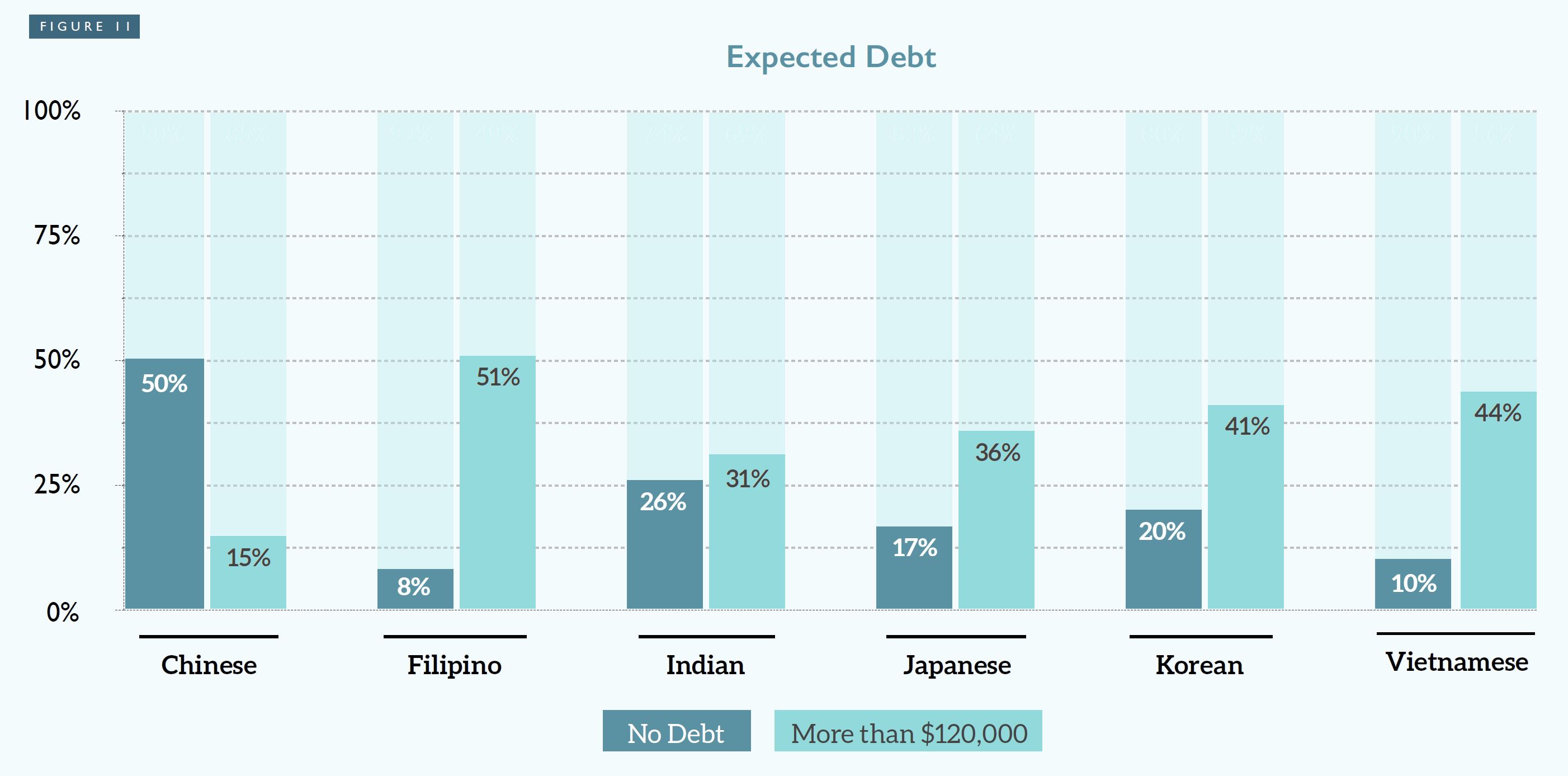

Taking time to drill down into the experiences of subgroups within Asian American communities yields a wealth of information about the similarities and, perhaps just as crucially, the divergent experiences of such a vast grouping. For instance, Vietnamese American students are half as likely as Indian American students to have parents who received a college education. Chinese students comprise 50% of the international students, who are generally not eligible for merit-based scholarships.

Diversity Within Diversity (2017)

Most troubling is that, in its Harvard litigation, SFFA claims to be concerned with assisting AAPI applicants against “negative action” by proposing as an alternative affirmative action based solely on income. Yet the group avoids acknowledging that such plans ultimately provide the greatest boost to white applicants—not racial minority applicants—because they do not account for additional systemic hurdles racial minorities from impoverished families face. Meanwhile, a ruling that would prohibit the use of race while leaving in place “colorblind” practices that unfairly benefit wealthy white applicants belies SFFA’s professed concern for Asian American applicants.

Rather than confounding admission programs, our current doctrine on race-conscious affirmative action does not prohibit law schools or colleges from assessing the multiple dimensions of advantage and disadvantage as they intersect with race (including for white applicants). To the contrary, it expects schools to assess individual applicants holistically. Students of color—including Asian American students—overcome barriers to the profession compounded by race alongside class, disability, gender, and other dimensions of inequality. Professor Lin’s first-hand experience with the inequities her family and neighbors faced remained central to her pursuit of legal advocacy, and now research and teaching, which investigate how law binds racial and economic injustice. Her unlikely route to academia would scarcely have been possible without the nuanced, race-conscious approaches intact in current doctrine.

Nonetheless, conservative proponents of “colorblindness” will soon ask the Justices to discard nearly 50 years of settled law on race-conscious admissions programs in higher education. At a time when debates over K-12 curricula foreground ideological attempts to silence all conversation about the ways in which race fosters systemic and institutional inequality, SFFA’s blunderbuss legal challenge has—at a minimum—reinvigorated examination of actual racial diversity so that legal academia, too, must take note.