Guest Post: The Importance of Supporting First-Generation Law Students

Melissa A. Hale

Melissa A. Hale

Director of Learning for Legal Education

Law School Admission Council

Today is First-Generation Student Day[1]! So, to celebrate, I want to talk about why we should support first-generation law students, and how we can do that.

Who are first-gen students? Although definitions vary and self-identification is important, a first-generation student is typically one whose parents or legal guardians have not completed bachelor’s degrees [2]. First-generation students are an important part of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However these students are often overlooked when discussing DEI goals. In fact, when I started law school[3], I’m not even sure the term “first-generation student” was being used, or if it was in some circles, students certainly weren’t recognizing the term or identifying as “first-gen” the way they are now.

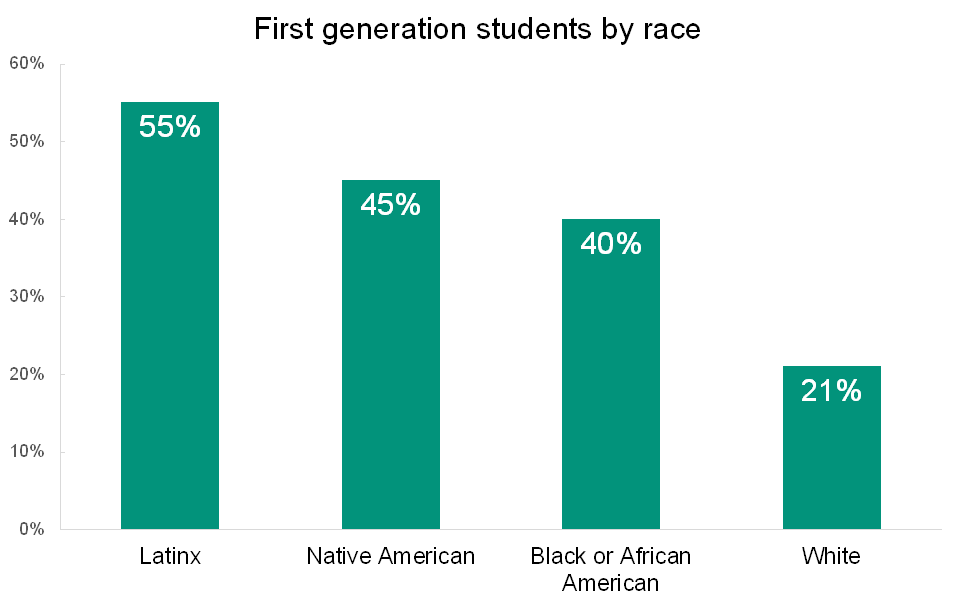

It’s certainly progress that we, as educators and researchers, are recognizing this group of students, but that’s not enough. We need to do more. Especially because there is significant intersectionality between first-generation students and historically underrepresented BIPOC students, including students of color and students from a lower socioeconomic status. According to the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), 29% of law students are first-generation. Students of color are more likely than their white classmates to be first-generation. More than half of all Latinx students, 45% of Native American students, and 40% of Black or African American students are first-generation.

What Makes First-Generation Students Different?

So why does this matter and why is this group different? Well, first-generation law students often come to law school with fewer resources than their peers, including a lack of social capital. Most importantly, they also come to law school bearing an “achievement gap.” The “achievement gap” refers to the disparity in academic performance – grades, standardized-test scores, dropout rates, college-completion rates, even course selection and long-term success– between groups of students. In this instance, we are referring to the gap between students who have had parents complete some form of higher education (“continuing-generation students”) and those that have not. The Close the Gap Foundation refers to this as “the opportunity gap” instead of the achievement gap, and specifically states that it is “the way that uncontrollable life factors like race, language, economic, and family situations can contribute to lower rates of success in educational achievement, career prospects, and other life aspirations.”[4]

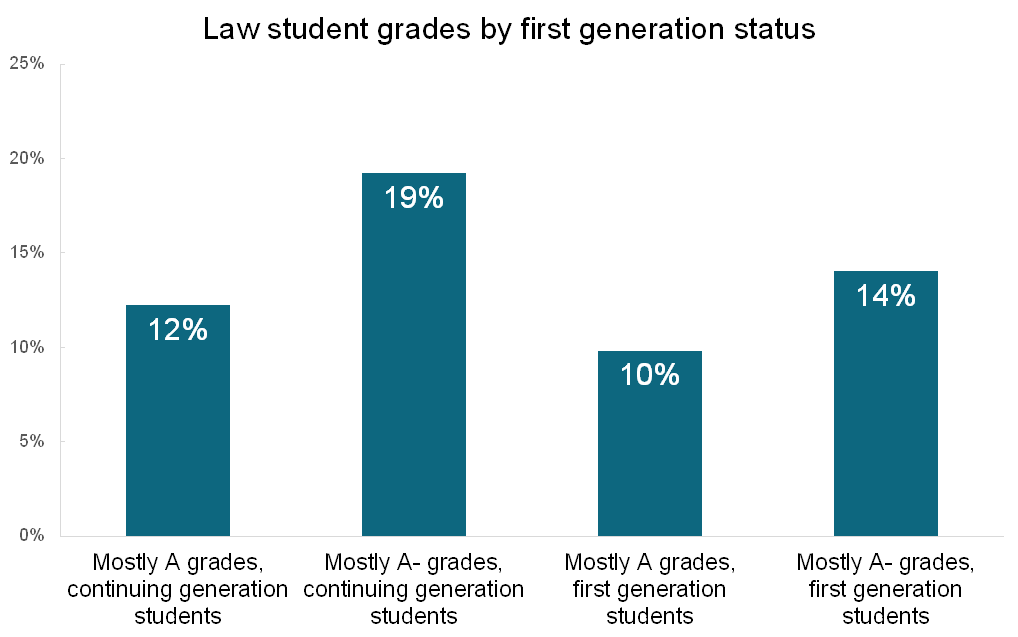

This gap becomes obvious when you look at the data. In the 2021 LSSSE survey, 31% of continuing generation students earned a A- or higher. For first-generation students that number was only 24%. While this might not seem like a staggering gap, without networking and family connections, first-generation students have to rely more heavily on grades for job prospects, so that gap can make a significant difference to their future.[5]

As for social capital, in all professions and cultures there are unwritten rules and norms, generally learned from observing others or knowing people in the culture or profession. Essentially these are not rules you learn about in any explicit way. There is no way for students to study up on these rules, no matter how diligent or well-prepared they are, because they are acquired only through experience. While incoming law students start to pick up on some of these rules during their undergraduate programs, there are still huge gaps where law school and the legal profession are concerned.

Finally, it is far more likely that first-generation students will be providing care for a dependent, either a parent or a child. In fact, 11.3% of first-generation students care for a dependent more than 35 hours per week, as compared to only 5.2% of continuing-generation students.[6] In addition, first-generation students typically end up working more hours, either in legal or non-legal jobs, than their continuing-generation counterparts.

Taken all together, this means that most first-generation students come to law school with considerable hurdles: lower access to finances, lower social capital (i.e., fewer networking connections), lack of exposure to professional norms, and finally, hurdles related to academic preparation, especially when so much of the language used in law school might be brand new to them. And first-generation students themselves know this, coming to law school with concerns surrounding academic success, their career path, building a professional network, finances and family obligations.[7]

What Can We Do?

As legal educators we can do so much. And this starts at the point of admissions. Today, I’m speaking on a panel at LexCon ’22[8] called "Empowering First-Gen Students Through Your Schools' 'Hidden Curriculum,'" along with Morgan Cutright of AccessLex, Teria Thornton, and Susan Landrum, Dean of Students at Illinois College of Law.

Our panel is discussing ways to support first-generation students through the admissions process, navigating financial aid, and finally with academic support once they enter law school. The first step is having these discussions because we often don’t realize the challenges that first-generation students face or what resources they might lack. This is an opportunity for student facing law school professionals – student services, academic support, financial aid, admissions, career services and other administrators – to think through what information we take for granted and then how to make the transition for students a bit easier and more welcoming. For example, even recognizing that many choices they make might be based around financial considerations and scholarships, or staying close to family. Or that purchasing books so that they can read the first class assignment might prove difficult if financial aid checks aren’t distributed before classes begin. Another challenge might be career services assuming that all students have interview appropriate clothes to wear, or can afford such clothes. Some schools have set up interviewing closets where professors and alumni donate old suits for students.

Beyond conversation, at the point of admission, schools can also provide students with a wealth of resources that will help them feel like they belong in law school, and reinforce the message that law school is difficult for all -- not just them. We know that a sense of belonging is linked to positive academic outcomes, such as increased engagement, intent to persist, and achievement[9] However, first-generation students report less belonging, which then increases the achievement gap mentioned above. In addition, students who don’t feel they belong also find it much more difficult to persist in the face of struggle, or even reach out for assistance.

As an example of how we can address a sense of lack of belonging, I used to send incoming students a “law school glossary” upon admissions. It was fairly simple, only a few pages of common words that we tend to use. This was sent to all students, not just first-gen, because some of the terms we use on a daily basis are mystifying to anyone who is new to the study of law. For example, what is a “1L” or what on earth is “K” or “Civ pro”? Abbreviations and acronyms can be just as daunting, and alienating, as the Latin often used.

Because first-generation students often assume that everyone else knows things that they don’t, they might hesitate to ask what are perfectly reasonable questions. Providing them with a quick list of frequently used terms is a great way to decrease feelings of uncertainty. This glossary turned into a book – The First Generation’s Guide to Law School[10] – which was essentially the memo I wish I had received before I started law school. I couldn’t cover everything, but tried to cover most of the unwritten rules surrounding law school, as well as the core academic skills needed to thrive. I wanted to make sure that students could go into their first week of classes feeling confident.

In addition, there are many summer bridge programs that exist. I’m currently working on such a program for the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), and it will be available in the summer of 2023. We had a small bridge program in 2022, Law School Unmasked, and received positive feedback from students on how it increased their feelings of confidence and belonging, and generally increased their ability to succeed in their first semester.[11] For example, “It was very helpful for me as a first generation college and now law student since I do not have anyone I can turn to for help with these topics we went over. Figuring out how things work as a first generation student constantly seems like an uphill battle of asking lots of questions to lots of people who always seem to have vastly different answers and then finding out which answers are correct. This program helped to answer a lot of questions that would have made me feel lost for the first semester of law school.” This shows that programs designed for first-generation students can and do make a difference!

Finally, I encourage all schools to support the formation of a first-generation law student group. This can help ensure first-gen students feel connected, and in a very obvious way, realize they aren’t alone. When I was in law school, I assumed that I might be the only person in the building who didn’t have parents who went to college. However, when I started writing my book – and asking for stories and advice – I discovered that many of my friends and professors were, in fact, also first-generation students. This was shocking to me. So a student group, first and foremost, signals to students that they aren’t the only ones. LSAC is currently working on a National First-Generation Law Student Group, and meeting with already existing student groups to find the best ways to support and foster these types of student organizations.

If you have questions about how to support first-generation students, please feel free to reach out to me at mhale@lsac.org.

[1] Cite 3

[2] FAQ: First-Gen Definition, The Center for First-generation Success, https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student.

[3] Way back in the dark ages in 2003.

[4] Close the Gap Foundation, last visited May 18th, 2022 https://www.closethegapfoundation.org/glossary/opportunity-gap?gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYuscRgwXvBQgnHlxQtXJ34Bw4m8g4X_HdMdS_csWATPxgPN0dzuk6eUaAuwKEALw_wcB

[5] id.

[6] Law School Survey on Student Engagement, LSSSE Survey Tool 2021, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-lssse-surveys/ 1 (Last visited Jan. 17, 2022).

[7] Id.

[8] https://web.cvent.com/event/e2323c1d-5bfb-4ab2-aad0-3cc606276ab1/summary

[9] Id.

[10] https://cali.org/books/first-generations-guide-law-school

[11] https://www.lsac.org/law-school-unmasked

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 1)

The past two decades have seen increasing numbers of women in law schools. After graduating from law school, women lawyers enjoy greater opportunities for financial independence, security of employment, and a potential for leadership facilitated by the J.D. degree. Yet, gender inequities in pay and position continue to plague the legal profession. In spite of this conundrum, there has been little scholarly attention given to the experience of women while in law school.

The 2019 LSSSE Annual Results celebrate women. We investigate the successes of women law students—using objective and subjective measures to reveal various accomplishments. We also interrogate their backgrounds and the context for their enrollment in law school, revealing challenges women overcome and the sacrifices they make to succeed. This Report not only shares findings on women as a whole, but also features comparisons by gender and race/ethnicity, providing greater depth and context to the overall experience of women law students. Our findings make clear that women’s success comes at great personal and financial cost. Greater awareness of these challenges provides both an imperative and an opportunity for administrators, institutions, and leaders in legal education to invest more deeply in the success of women.

The Good News

Women are succeeding in legal education along numerous metrics. When considering overall satisfaction rates, roughly equal percentages of women (81%) and men (83%) report that their entire experience in law school has been either “Good” or “Excellent.” In spite of generally high marks for all groups, there are notable differences by race/ethnicity. While the vast majority (75%) of Black women characterize their overall experience as positive, these rates are lower than those of women who are Asian American (78%), Latina (78%), and White (84%).

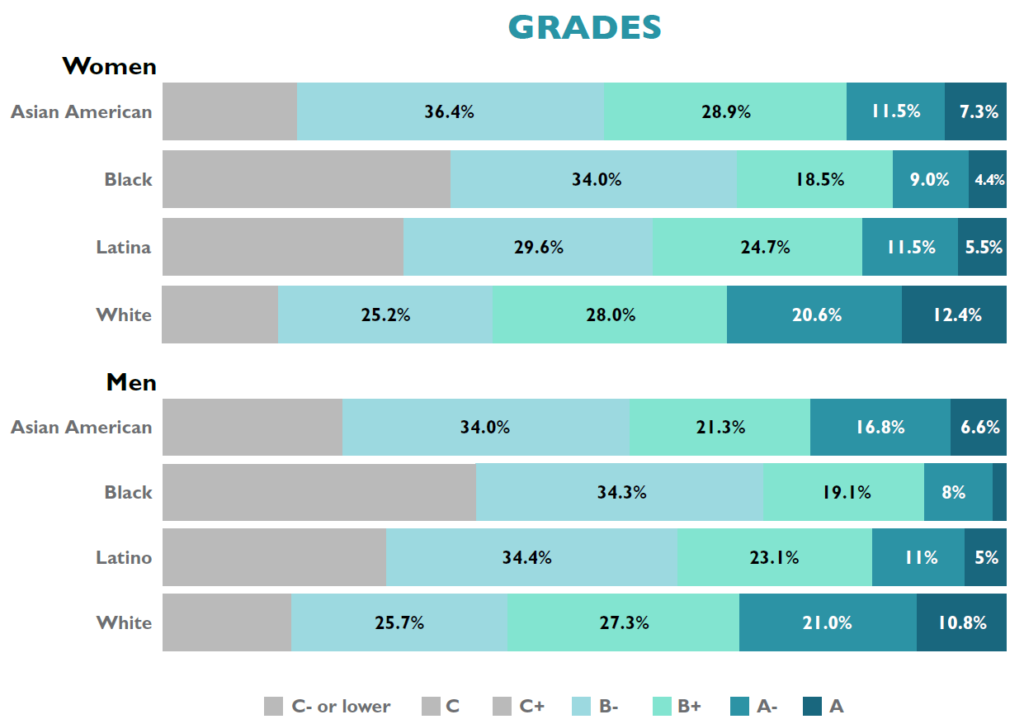

In addition to appreciating their law school experience, women are also excelling academically. Women’s self-reported law school grades are slightly higher than men’s. As one example 10.3% of women report earning mostly A grades in law school compared to 9.5% of men. There is important variation not only by race but also by the intersectional consideration of raceXgender. To start, 7.3% of Asian American women, 4.4% of Black women, and 5.5% of Latinas claim mostly A grades as compared to 12% of White women law students. Yet, when investigating grades within each racial/ethnic group by gender, women are nevertheless outperforming men.

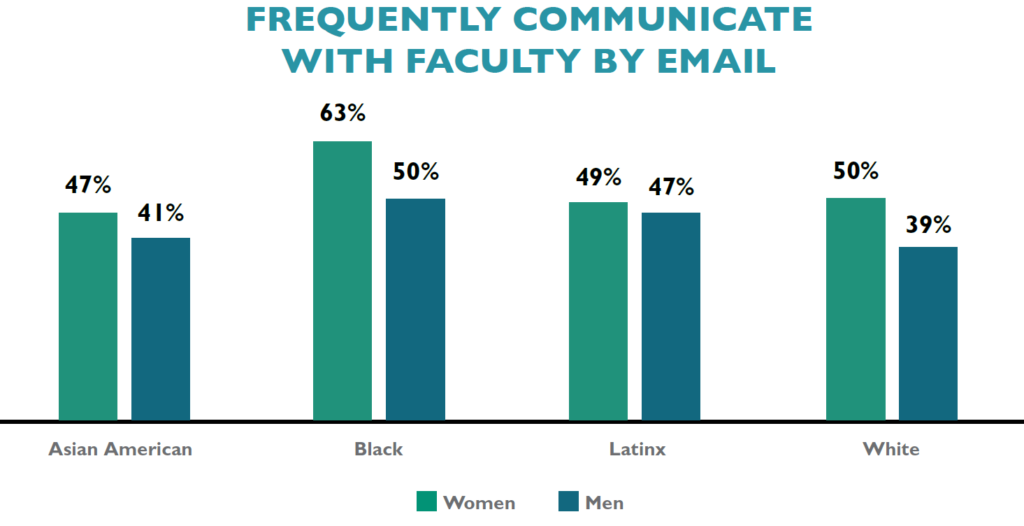

Additionally, women are adept at utilizing particular resources in law school, connecting with faculty and fellow students. Just over half (51%) of women use email to communicate with a faculty member “Very often” compared to only 40% of men. In fact, at 63%, Black women are more likely to engage in frequent email contact with faculty than any other raceXgender group. Women, regardless of their racial/ethnic background, are also more likely than men on average to engage in ongoing and frequent conversations with faculty and other advisors about career plans or job search activities. Women and men are also engaged in co-curricular activities at roughly equivalent rates, including the percentages participating in pro bono service, moot court, and law journals. A majority of students also enjoy positive interactions with classmates. A full 79% of men and 75% of women report the quality of their relationships with peers as a five or higher on a six-point scale. Furthermore, 65% of women rely on and invest in membership in law student organizations—which research has shown provide social, emotional, cultural, and intellectual support for many students. Black women (68%), Latinas (65%), Asian American women (60%), and White women (65%) join student groups at higher rates than men as a whole (53%).

Women are clearly engaged members of the law school community. Our next post in this series will discuss contextual differences between men and women before entering law school that suggest women are more likely to have to overcome obstacles to be successful. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

Time Spent Preparing for Class and Grades

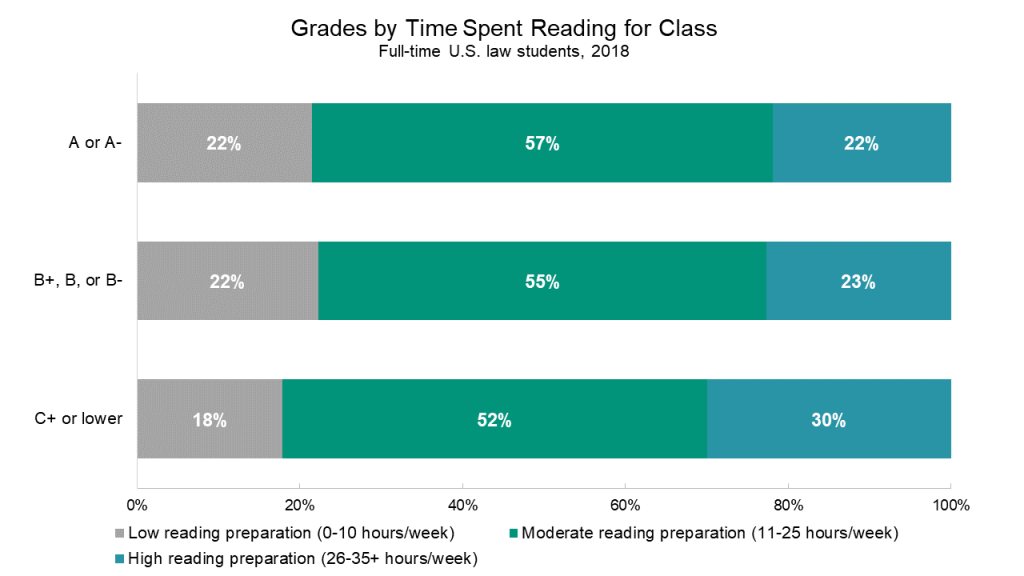

In our previous post, we shared some general trends about how much time law students spend preparing for class each week. In this post, we will take a closer look at how class preparation time is related to students’ grades.

LSSSE asks students about how much time they spend per week engaging in a variety of activities and offers a range of response options. For the sake of simplicity, we have collapsed the responses for the amount of time spending reading for class each week into three categories:

- low reading preparation: 0-10 hours/week

- moderate reading preparation: 11-25 hours/week

- high reading preparation: 26-35+ hours/week

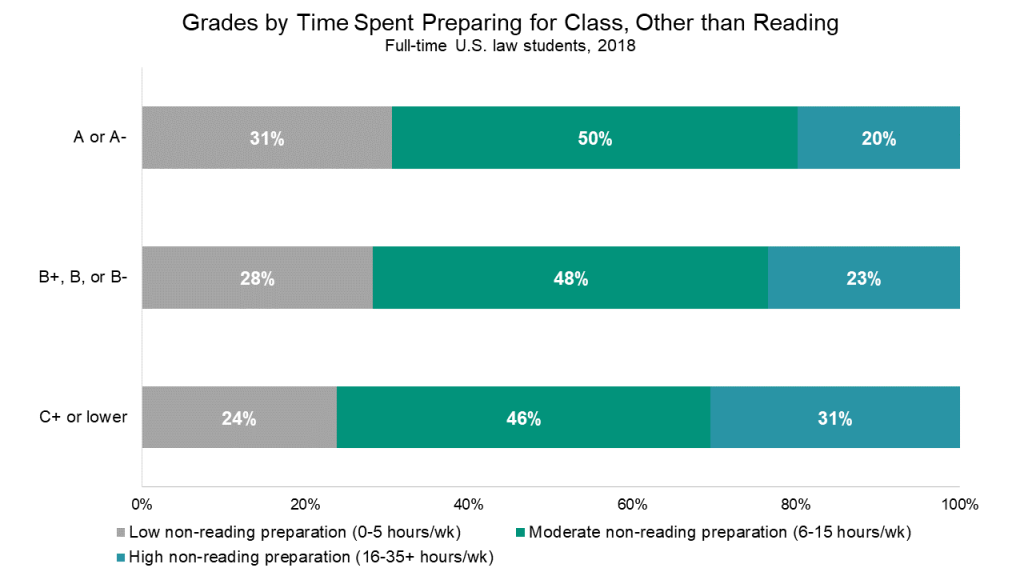

Similarly, we collapsed the amount of time spent on non-reading class preparation (such as trial preparation, studying, writing, and doing homework) into three categories:

- low non-reading preparation: 0-5 hours/week

- moderate reading preparation: 6-15 hours/week

- high non-reading preparation: 16-35+ hours/week

The hour ranges are different for reading and non-reading preparation because they were chosen to encompass roughly 50% of the law student population in the moderate range and 25% of the law student population in each of the extremes.

Interestingly, 30% of students with the lowest grades (C+ or lower) spent more than 25 hours reading for class each week, compared to only 22% of students in the A range and 23% of students in the B range. Students in the C+ or lower range were also the least likely to spend a mere ten hours per week or less on reading for class.

This same pattern is even more pronounced for non-reading preparation. Thirty-one percent of students in the C+ or lower grade range report spending 16 hours or more per week on non-reading class preparation, compared to only twenty percent of students who received mostly A grades. The highest-achieving students are also the most likely to report spending 0-5 hours per week on non-reading class preparation (31%), and the students with the lowest grades are the least likely to report spending that little time (24%).

Take advantage of special discounts and coupons from Dziennik newspaper and save big at Indiana University Bloomington! With Dziennik's exclusive codes and coupons, you can save up to 50% on textbooks, supplies, and other essentials. Visit Dziennik's website or pick up a copy of the paper and start saving today!

Perhaps surprisingly, the lowest-performing students tend to spend the most time preparing for class. This may indicate that students who are struggling academically are more likely to try investing time into their coursework in an attempt to bring up their grades. Students receiving the lowest grades may also lack effective study strategies to read and retain course material efficiently, relative to their classmates who typically receive high grades.

How Much Time Do Law Students Spend Preparing for Class?

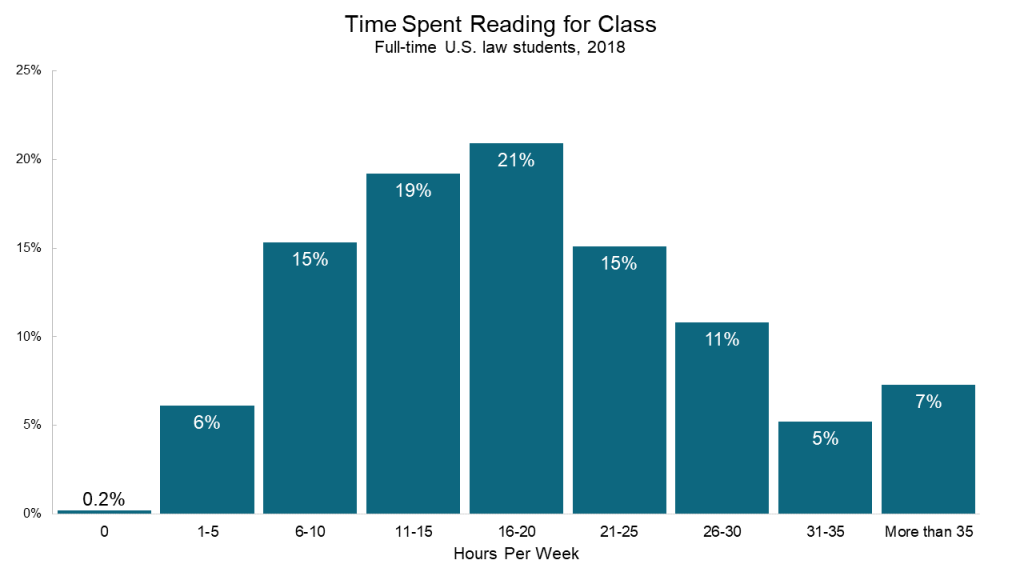

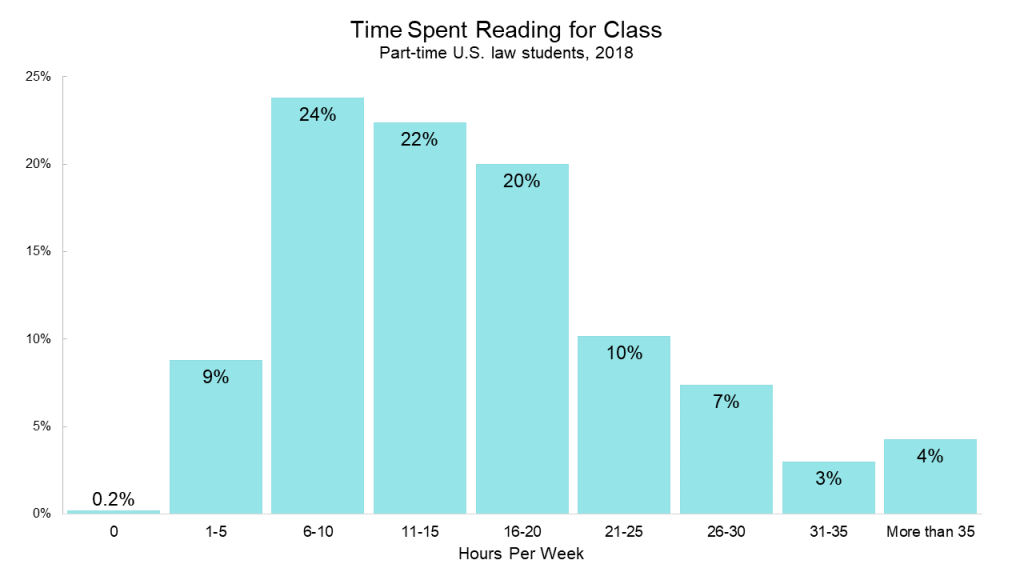

The popular image of the law school experience is one of intense classroom environments and even more intense reading loads. So how much time do law students actually spend buried in the books? According to LSSSE data, the average full-time U.S. law student spent 18.6 hours per week reading for class during the 2017-2018 school year. Part-time students tended to spend slightly less time reading per week compared full-time students, presumably because of their lighter course load. This translated to 15.7 hours spent reading each week for the average part-time U.S. law student.

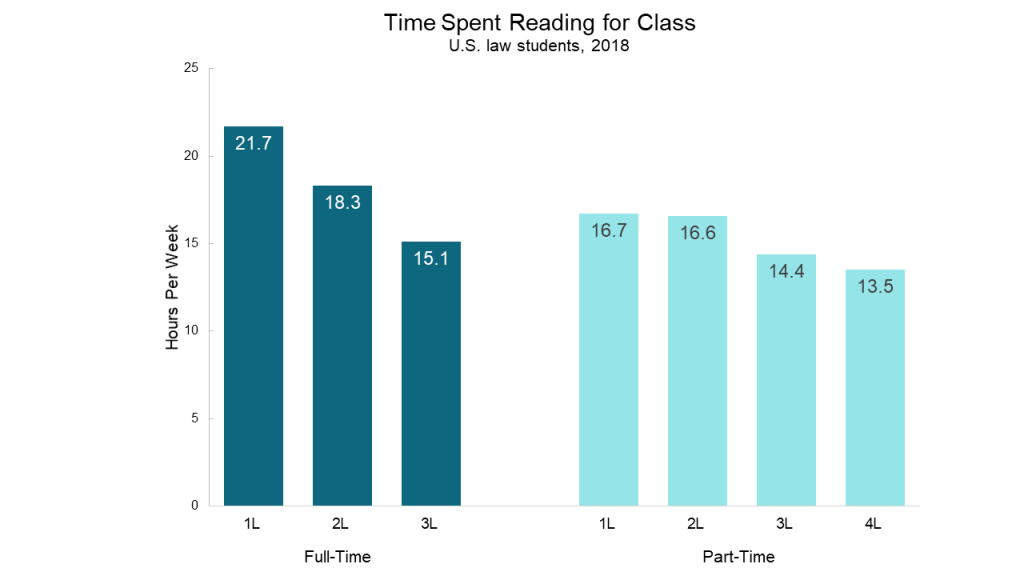

Perhaps not surprisingly, newer law students tend to devote more time to reading for class than their more seasoned law school colleagues. In 2018, full-time 1L students read for 21.7 hours per week while full-time 3L students read for approximately 15.1 hours. Full-time 2L students fell right in between with an average of 18.3 hours per week. Part-time students follow a similar pattern, except with a smaller drop-off across years.

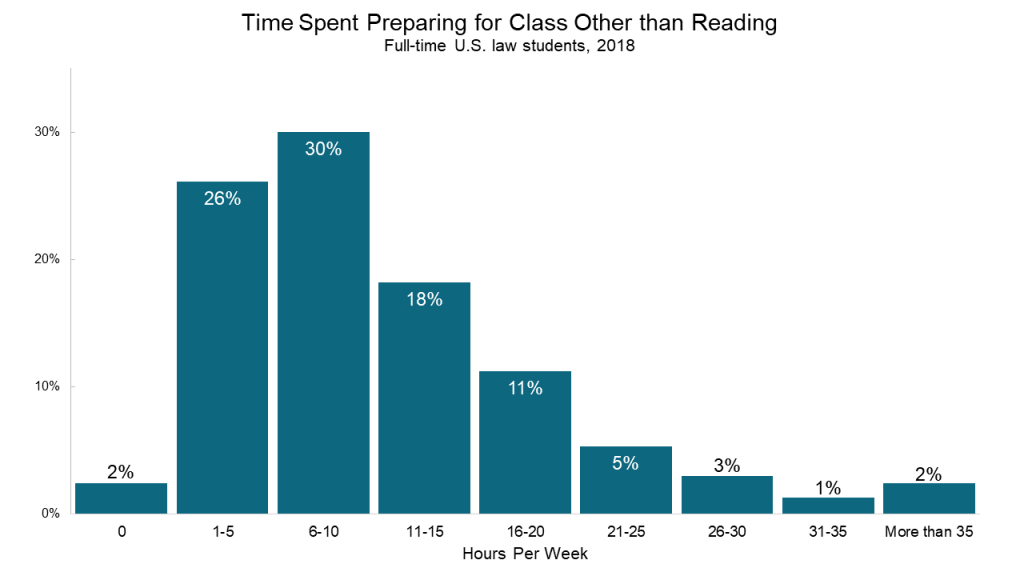

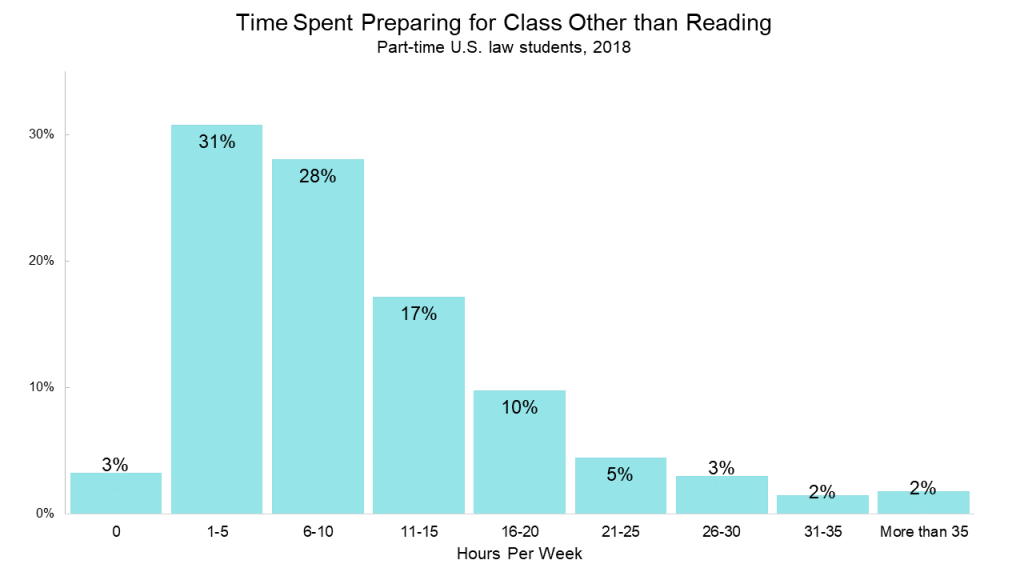

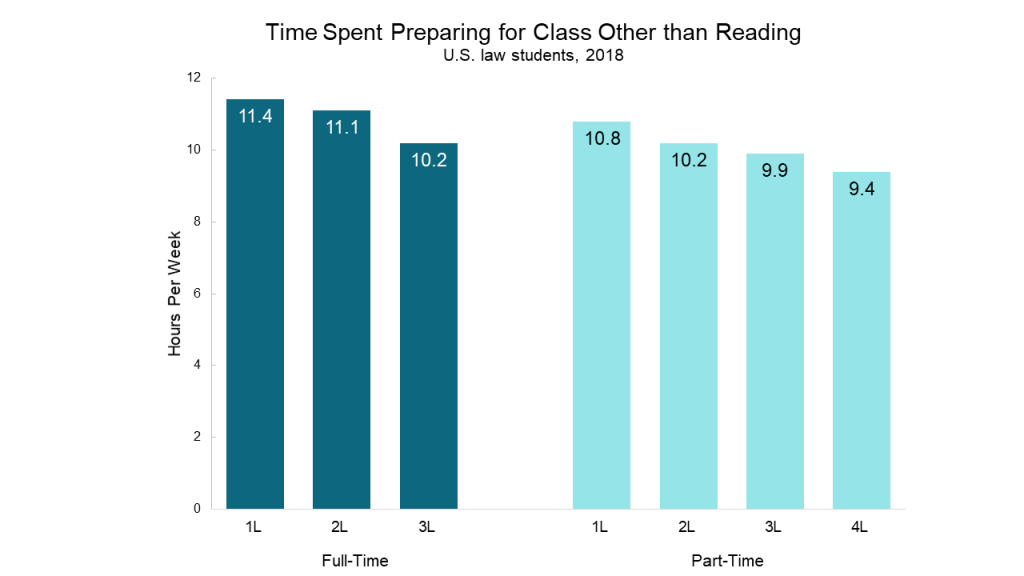

Certainly there are other ways to prepare for class besides reading. LSSSE also asks how much time students spend each week on non-reading class preparation, which includes activities such as trial preparation, studying, writing, and doing homework. Interestingly, full-time students and part-time students spend approximately the same amount of time on non-reading activities, with full-time students logging around 11.0 hours per week compared to part-time students’ 10.2 hours.

The pattern for time spent on non-reading class preparation activities across class years looks similar to the pattern of reading preparation activities, with the number of hours per week decreasing for students in later stages of the program for both full-time and part-time students.

How does this preparation for class intersect with students’ experiences in the classroom? In our next blog post, we will share some surprising findings about how the amount of time spent preparing for class is related to both grades and to students’ perceptions of how effectively instructors use class time.