Part 1: Part-Time Students & the Law School Experience

Around 12% of law students attend part-time. This subpopulation of law students has a unique experience that differs from that of their full-time colleagues. In part one of this two-part series, we will explore the characteristics of part-time law students and describe some of the ways that they engage with the law school community and environment. In part two, we will look at how satisfied part-time students are with their law schools and the extent to which they feel supported in their success as students and as future legal professionals.

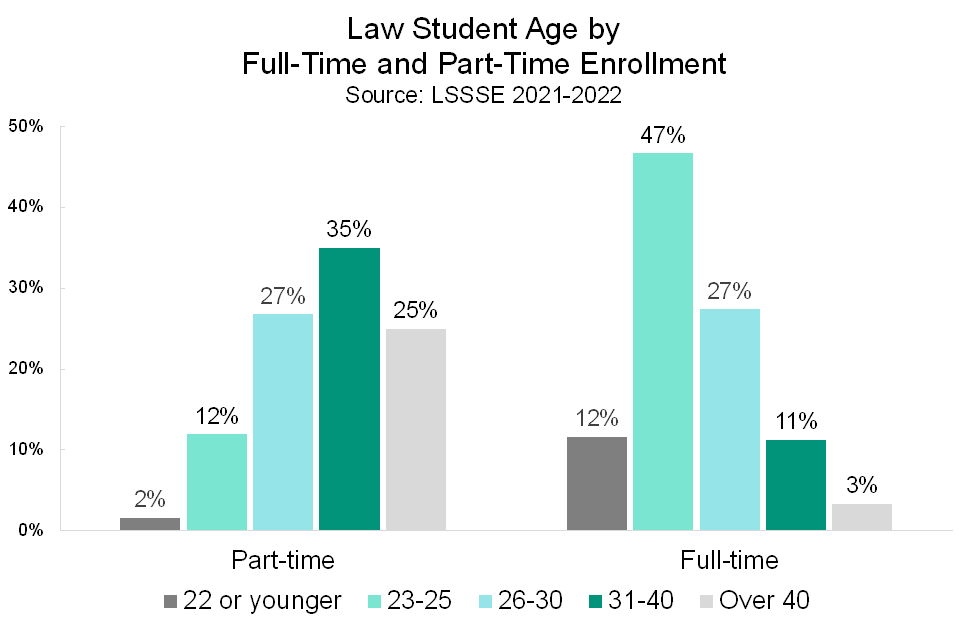

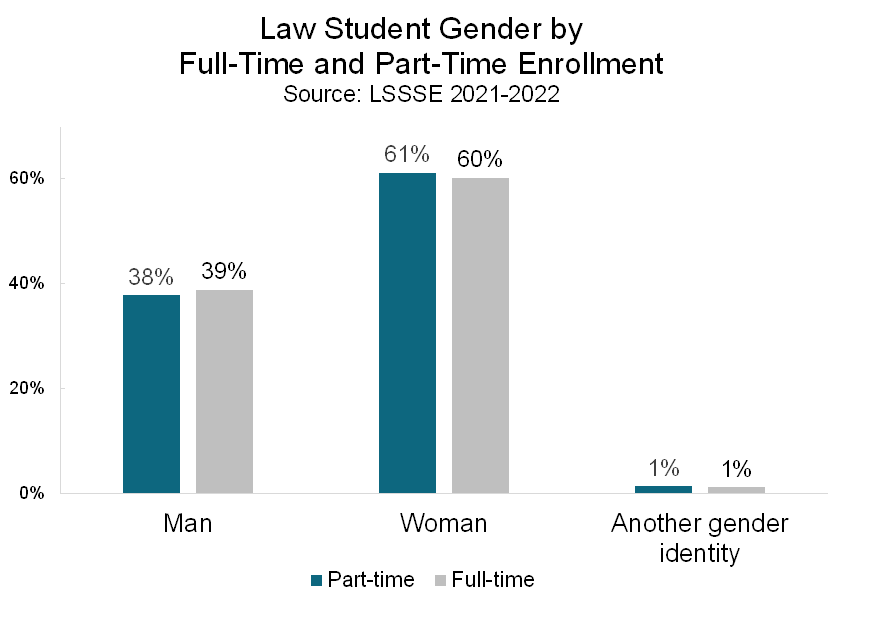

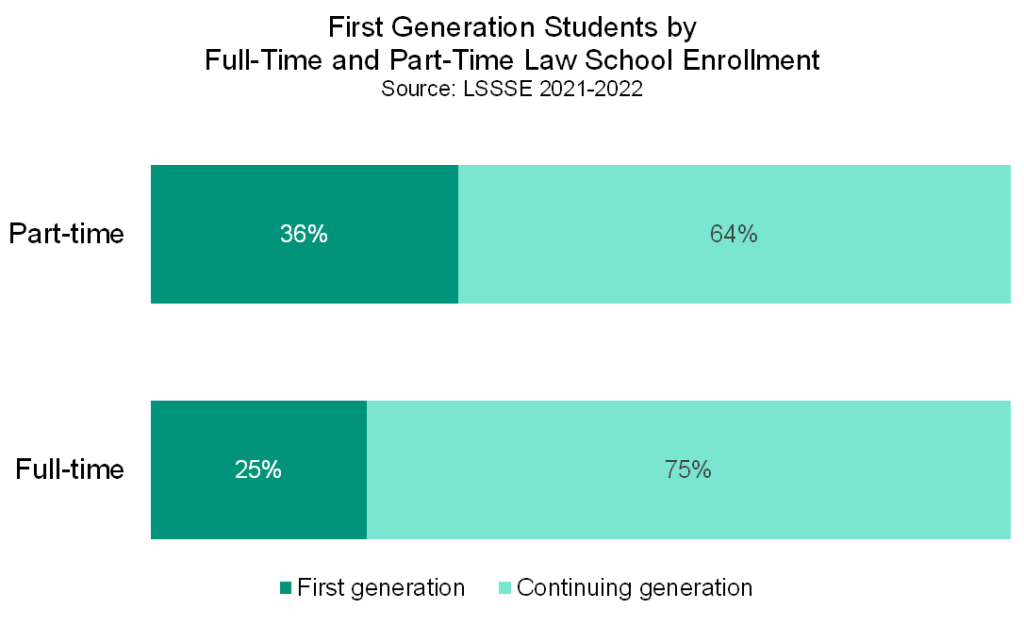

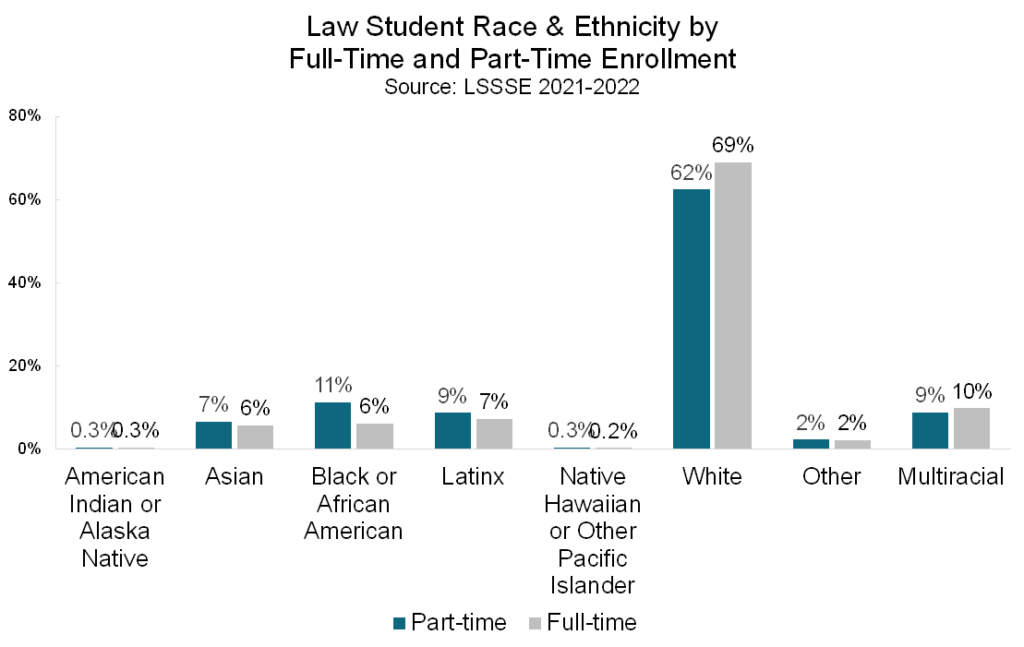

Part-time students tend to be somewhat older than their full-time classmates. Sixty percent of part-time students are over thirty years old compared to 14% of full-time students. In fact, one quarter (25%) of part-time students are over 40 compared to just 3% of full-time students. However, the proportions of men, women, and people of another gender identity are about equal between the two groups. Part-time students are more likely to be first generation (defined as a person whose parents did not graduate college) with over a third of part-timers (36%) falling into this category compared to only a quarter (25%) of full-timers. Part-time students are also more likely to be Black or Latinx.

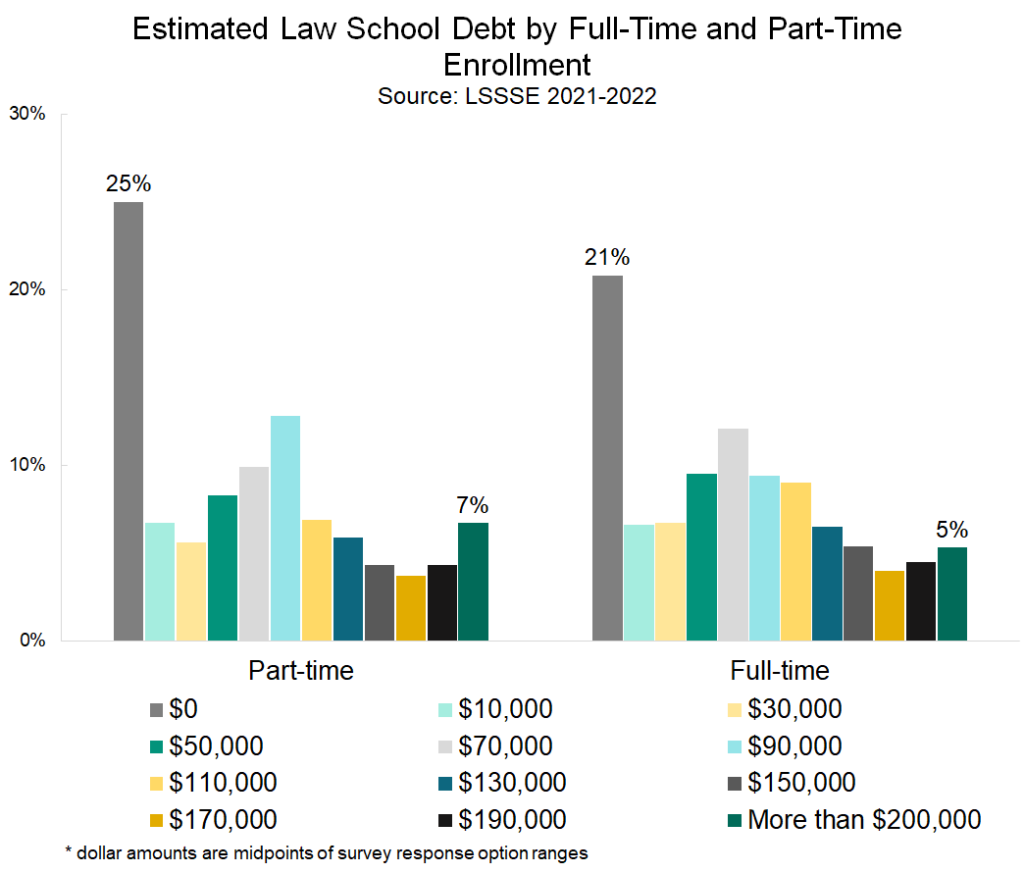

Part-time students are more likely than full-time students to expect to have no law school debt upon graduation, possibly because some part-time students are attending law school with the financial support of their employers. However, part-time students are also slightly more likely than full-time students to expect to owe more than $200,000, which is the highest debt category that LSSSE records. Seven percent of part-time students expect to owe this much compared to five percent of full-time students.

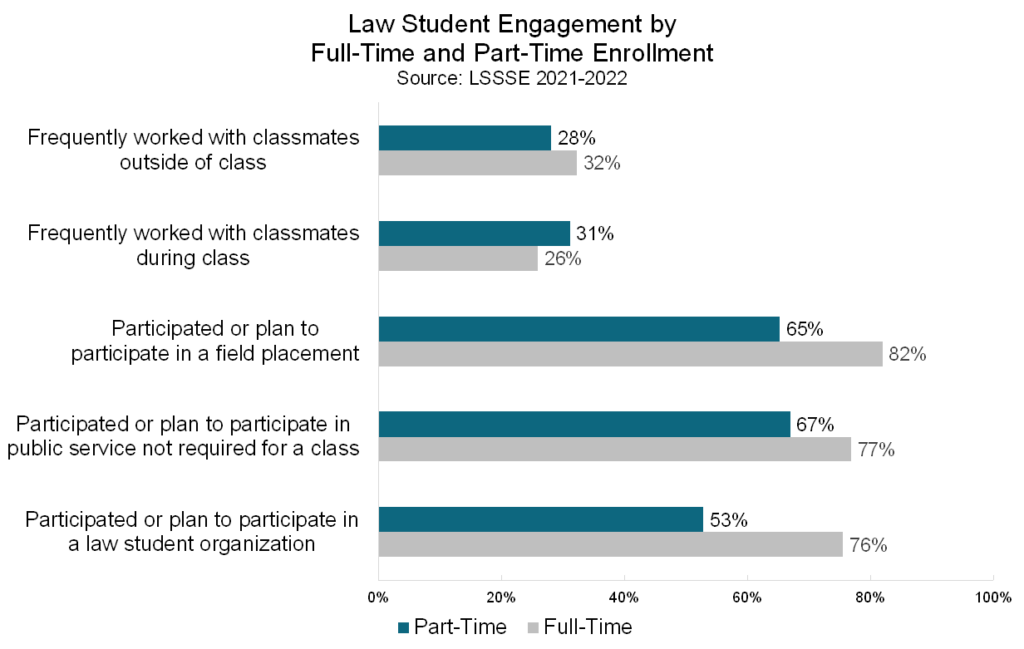

In terms of engagement with their coursework, more full-time students than part-time students frequently work with classmates outside of class to prepare class assignments. However, more part-time students frequently work with other students on projects during class time. Part-time students are somewhat less likely to engage in enriching experiences than their full-time counterparts, perhaps because they are more likely to have more intense work and family responsibilities. Still, about two-thirds (65%) of part-time students have completed or plan to participate in field placements and about two-thirds (67%) of part-time students have completed or plan to participate in public service. Additionally, over half (53%) of part-time students will join a law student organization before graduation. Part-time students are less likely than full-time students to partake in these opportunities, but their participation rates are still reasonably high given the other demands on their time.

Part-time students find ways to make the law school experience their own. This group of students tends to be older and slightly more ethnically diverse, and they are somewhat less likely to add enriching law school experiences to their schedules. In our next post, we will examine part-time students’ feeling toward their law schools and the support they receive from faculty and administrators.

Success with Online Education: Classroom Environment

Our last post shared some general findings about online learning from our 2022 Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf). In this post, we will share evidence that online classrooms appear to encourage a more diverse cross-section of students to participate in class discussions. We will also share reassuring signs that online law students are learning as much as their in-person counterparts.

Online discussions feature diverse voices

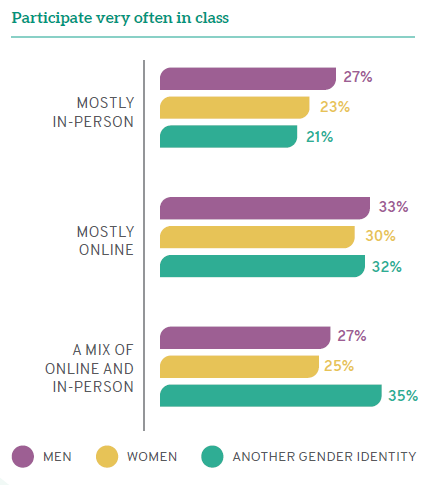

Online classes excel at inviting participation from a broader range of students than in-person classes. Men are equally likely to participate in class discussion and ask questions “often” or “very often” whether participating in person (60%) or online (61%). However, women taking mostly online courses are more likely to engage in class “often” or “very often” (58%) compared to women taking mostly in-person courses (53%). In fact, online courses appear to encourage all students to engage more intensely with class discussion. One quarter of students (25%) who take primarily in-person classes participate “very often” compared to 31% of students taking mostly online classes. There is a marked gender difference, with 23% of women participating “very often” in person but a full 30% participating “very often” online, and only 21% of those with another gender identity participating “very often” in person while 32% do so online. The online environment–perhaps because of the mechanisms for turn-taking or because it is more comfortable for students to volunteer– invites more voices to engage in the conversation.

Online students are learning as much as in-person students

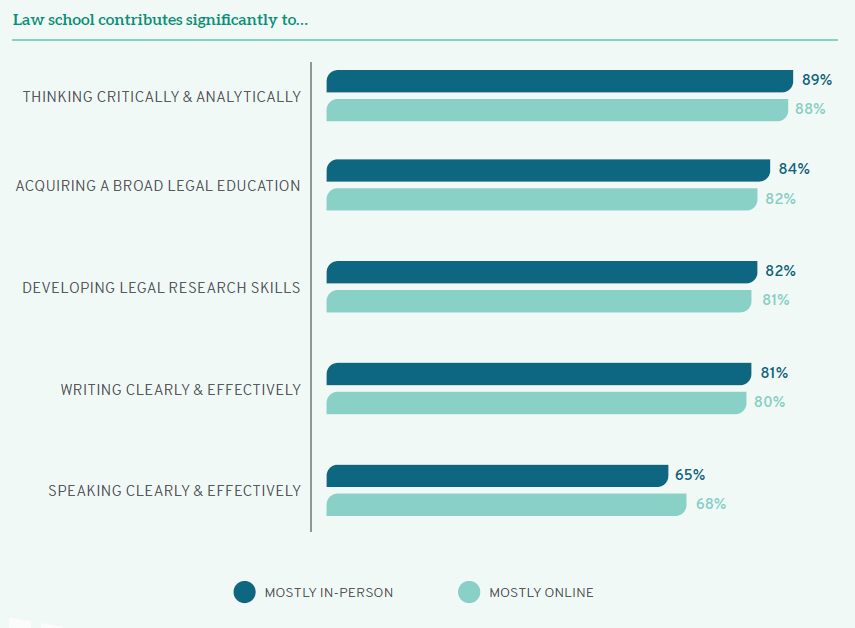

Regardless of how they attend classes, most students are confident that they are developing crucial legal skills. Nearly 90% of online and in-person students are learning to think critically and analytically. More than four out of five online and in-person students say they are acquiring a broad legal education (82% and 84%, respectively) and developing legal research skills (81% and 82%, respectively). Interestingly, online students are more likely to be developing the ability to speak clearly and effectively, perhaps because online courses invite more participation from a diverse range of students. Thus, law school classes do not lose their intellectual rigor when they are offered in an online format.

Online law school classes can be highly successful and well-received by students. Many students who take most of their classes online are as satisfied—and sometimes more satisfied—than their peers who attend classes primarily in person. Furthermore, law students who attend classes via either modality are equally likely to feel confident that they are learning important skills that will help them succeed as legal professionals. Although the law school experience is unlikely to be primarily online again, the accelerated transition to offering online courses that occurred due to COVID-19 shows that the online law school experience can be as successful, enriching, and satisfying as the traditional law school curriculum.

What Do 1L Students Plan to Do in Law School?

Most students complete law school in three years. With intense coursework and notoriously challenging reading loads, law students must be selective about how they allocate their time toward extracurricular activities. Which enriching activities had 1L students completed or planned to complete before graduation in 2019 and 2020? Check out our interactive visualization below to see.

** Note that non-binary students are included only when the population was large enough to ensure student anonymity in aggregate reporting.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 3)

Opportunities for Improvement

Given the many challenges facing women upon entry to law school, it is no surprise that there are also opportunities to improve the experience for women students in legal education. LSSSE data on concepts as varied as classroom participation, caretaking, and debt make clear that women need greater support.

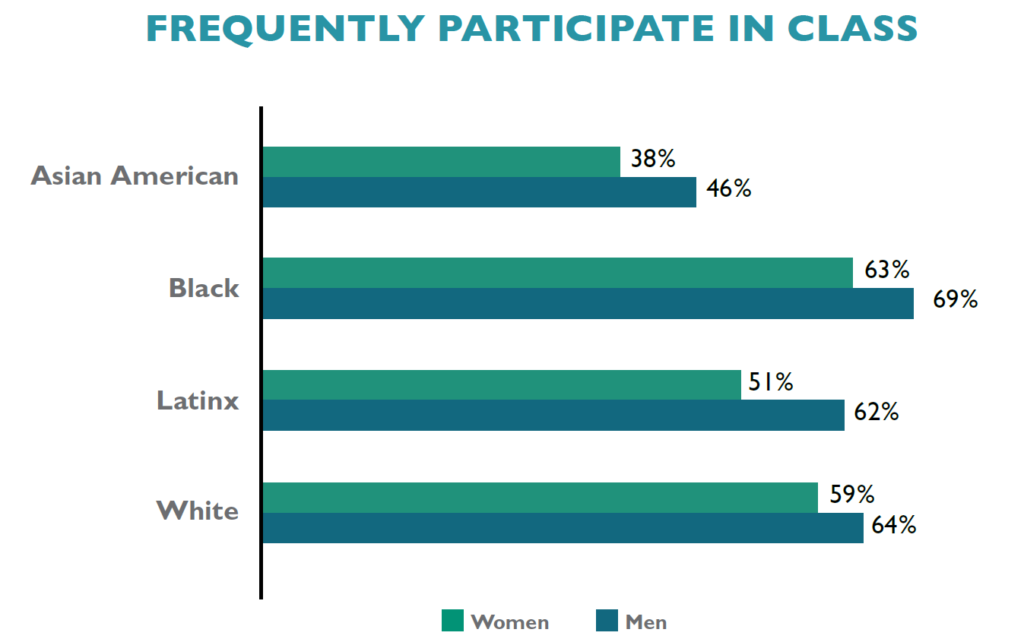

Engagement in campus life is an especially significant indicator of success. Law students who are deeply invested in both classroom and extracurricular activities tend to maximize opportunities for success overall. As stated in a previous post, women are just as likely as men to be involved in various co-curricular endeavors. Yet, smaller percentages of women than men are deeply engaged in the classroom. While 64% of men report that they “Often” or “Very Often” ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions, only 58% of women do. This gender disparity remains pronounced within every racial/ethnic group, as men participate in class at higher rates than women from their same background. There are also interesting variations by raceXgender, with Black men frequently participating at higher rates than any other group (69%), and at almost twice the rate of Asian American women (38%).

Many women students also spend numerous hours during their law school careers providing care to household members. For instance, 11% of women report that they spend more than 20 hours per week providing care for dependents living with them, as do 8.6% of men. These competing responsibilities require a significant investment of time, which could otherwise be spent on studying for class, working with faculty on a project outside of class, or even engaging in leisure activities. Instead, these students are taking care of their families.

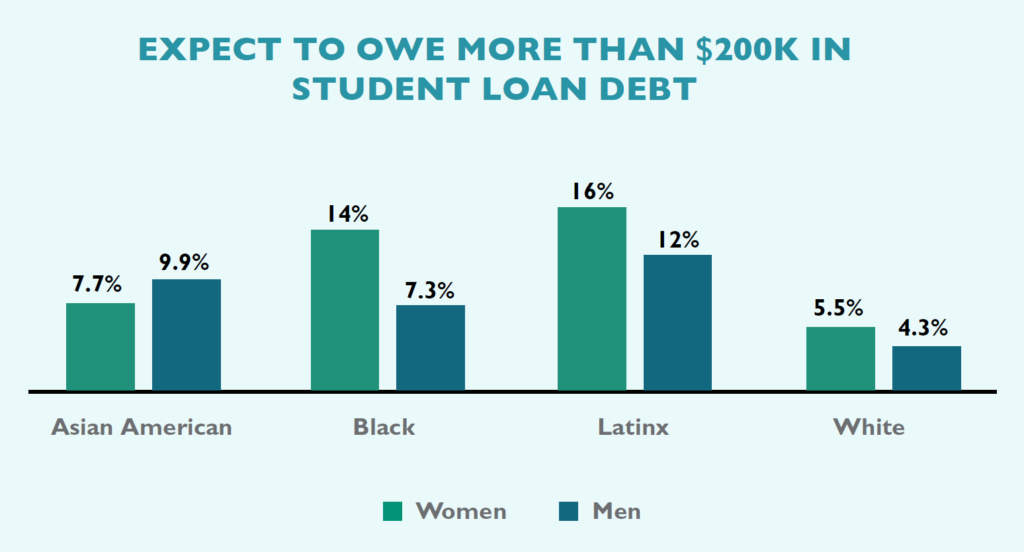

An especially troubling discovery is that high percentages of women than men incur significant levels of debt in law school. Among those who expect to graduate from law school with over $160,000 in debt are 19% of women and 14% of men. This gender difference remains constant within every racial/ethnic group. Even more alarming is the disparity among those carrying the highest debt loads: 7.9% of women will graduate from law school owing over $200,000 as compared to 5.5% of men. LSSSE data not only confirm existing research on racial disparities in educational debt, with people of color and especially Black and Latinx students borrowing more than their peers to pay for law school, but also reveal that women carry a disproportionate share of the debt load as compared to men. Furthermore, when considering the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, we see that women of color specifically are graduating with extreme debt burdens.

Next week, we will conclude this series with some troubling trade-offs that women make to overcome the disadvantaged position in which they often find themselves relative to their male counterparts. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.