Law School Support for Non-Academic Responsibilities

Law students vary in their amount and type of non-academic responsibilities, and they also vary in the degree to which they feel that their law school helps them cope with these responsibilities. In addition to their studies, some law students work, care for children or other dependents, and engage in community activities. We wanted to examine the degree to which students feel supported in these endeavors by their law schools.

Time Spent Caring for Dependents

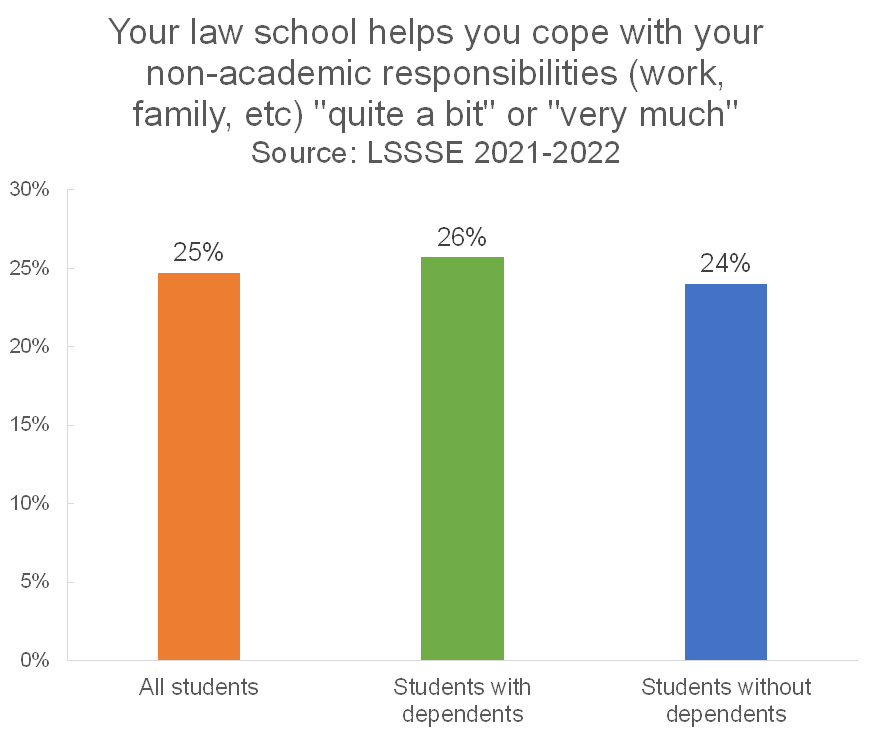

Thirty-eight percent of law students spend at least one hour per week caring for dependents living with them (parents, children, spouse, etc.). Interestingly, there is little difference in the percentage of students with and without dependent care duties who feel that their law school emphasizes helping them cope with their non-academic responsibilities. About a quarter of each group (26% of students with dependents and 24% of students without dependents) feel well-supported. However, students with dependents are slightly more likely to say that their law school does very little to help them cope with non-academic responsibilities. Two out of five (42%) of students with dependents feel this way compared to 38% of students without dependents.

Gender and Dependent Care

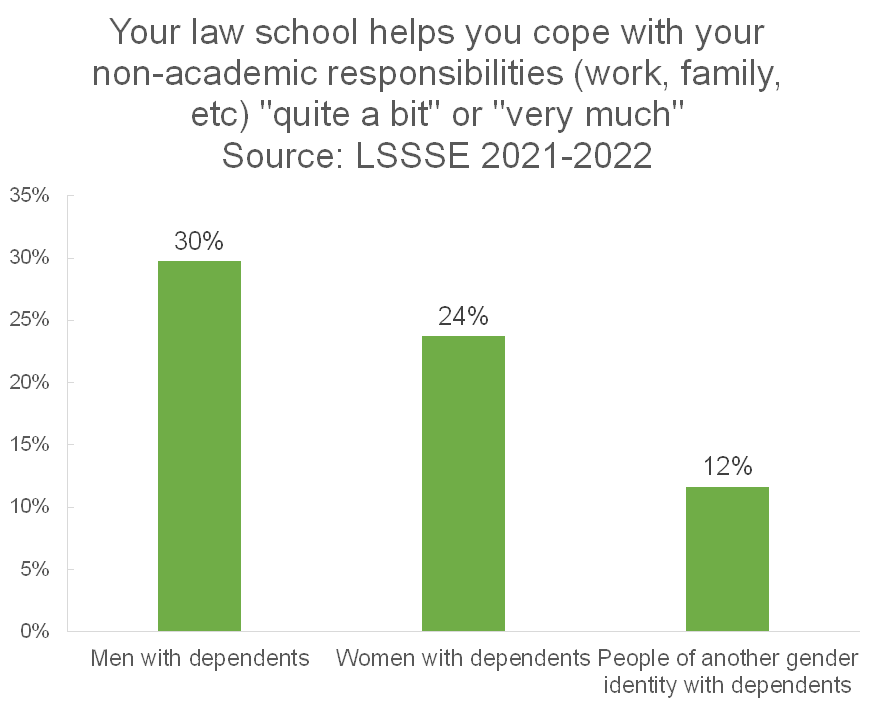

However, there are huge differences by gender. Men with dependent care responsibilities are much more likely to feel supported by their law schools than women with dependent care responsibilities, and both groups feel more supported than people of other gender identities with dependent care responsibilities.

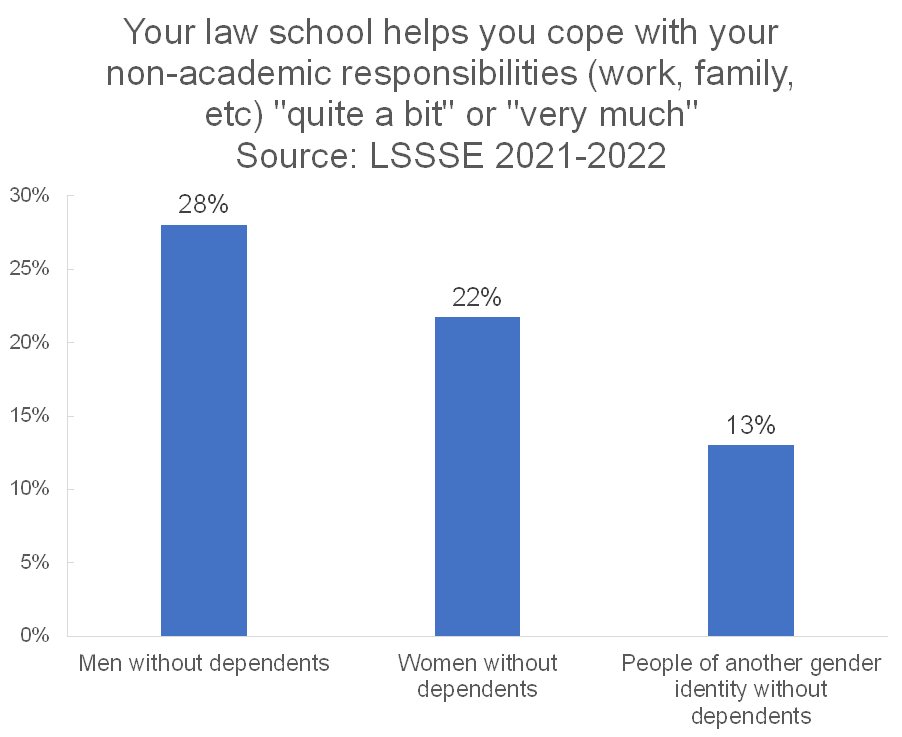

It appears, however, that this effect is more about gender and less about the dependent care responsibilities as we see this same disparity across gender among people without dependent care responsibilities.

Time Spent Working for Pay

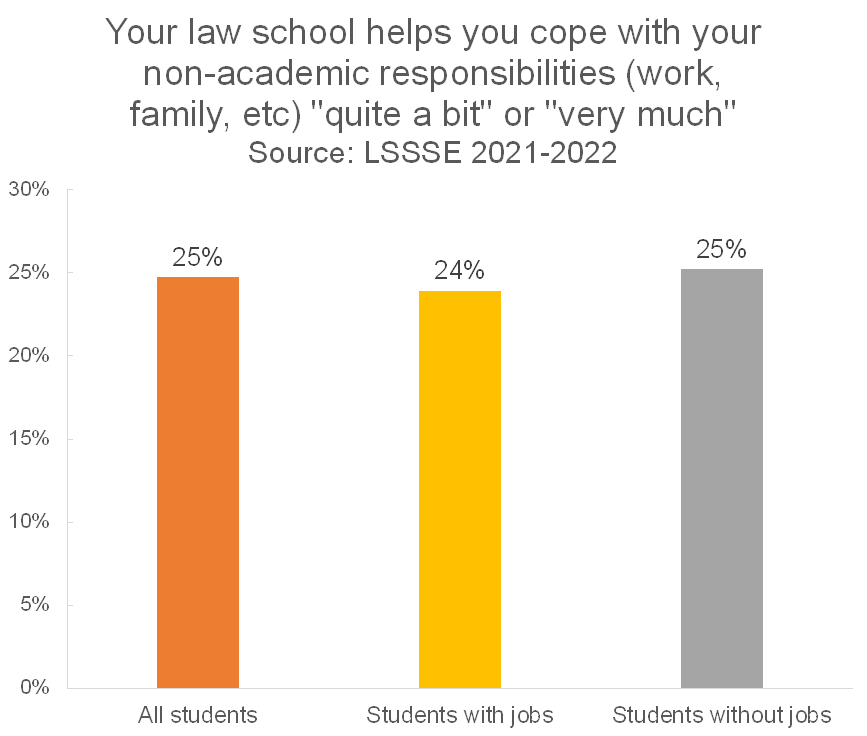

Similar to the pattern we see with dependent care duties, there is minimal difference in the perceived level of support for non-academic responsibilities between students who have jobs and students who do not. Around one in four students in either category say that their law school emphasizes supporting their non-academic responsibilities.

Gender and Employment

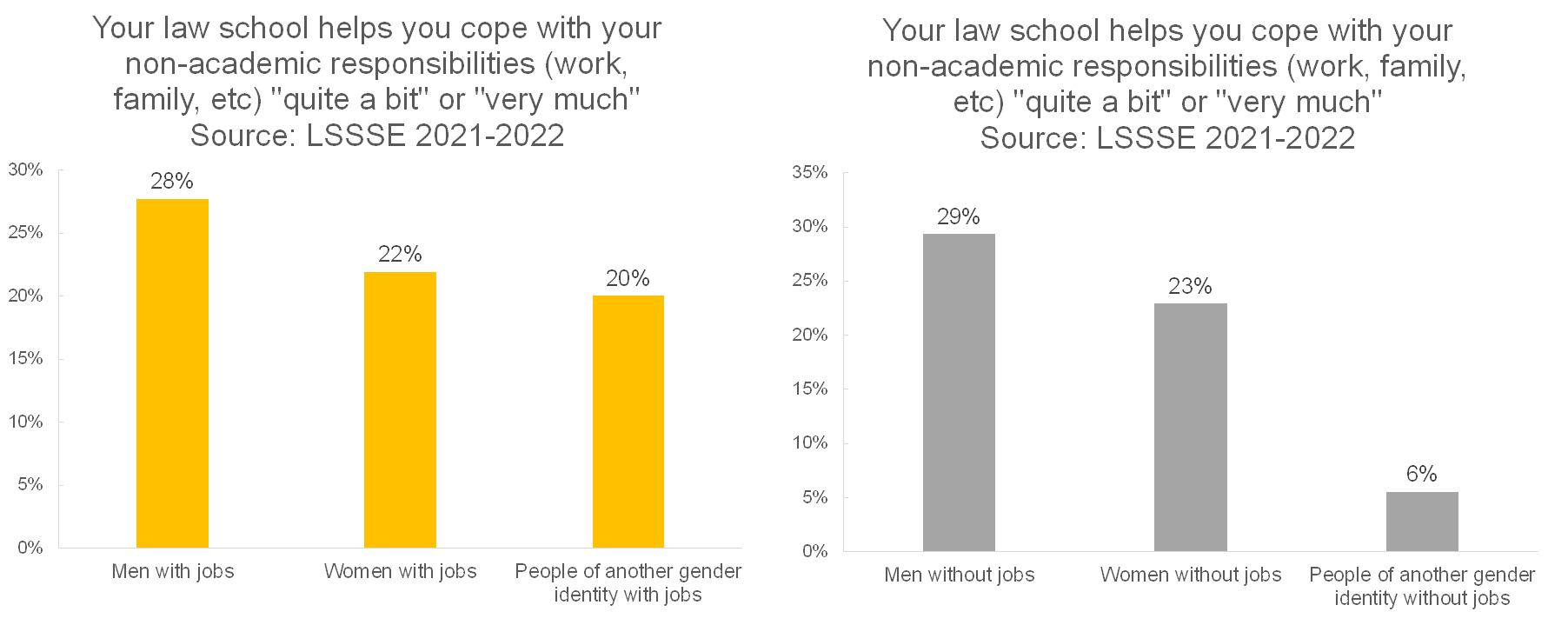

The gender pattern for perceived support is much the same for working/non-working students as it is for dependent care duties. Men are more likely to feel high levels of support than other students. However, people who identify as neither men nor women are actually more likely to feel highly supported in their non-academic responsibilities when they are employed (20% of students) relative to when they are not (6% of students).

Regardless of how they spend their time outside of law school, men are much more likely to feel highly supported in their non-academic responsibilities, people of another gender identity are very unlikely to feel supported, and women generally fall somewhere in between. Adequate support for non-academic responsibilities clearly looks different for different people, and it appears that gender is a major factor. Rather than focusing on student populations based on which responsibilities they have and how they spend their time outside of the classroom, law schools may want to consider the unique needs of women and people of other gender identities to close the gap in the degree of support they feel about coping with their non-academic responsibilities.

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Jonathan Todres

Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law

Georgia State University College of Law

An unhealthy work-life balance is an all-too-familiar phenomenon in law school, as well as for the legal profession. Mental health and substance use issues have been well-documented in the profession, and a breadth of research shows the detrimental effects of law school on many students’ well-being. All that was true before the COVID-19 pandemic inflicted its double burden—increasing the number of students who are suffering, and exacerbating the extent of harm experienced by those who were already struggling. Of course, there are many underlying causes that demand urgent attention, but an often-overlooked issue is the nonstop work culture of law school that discourages students from taking any time off.

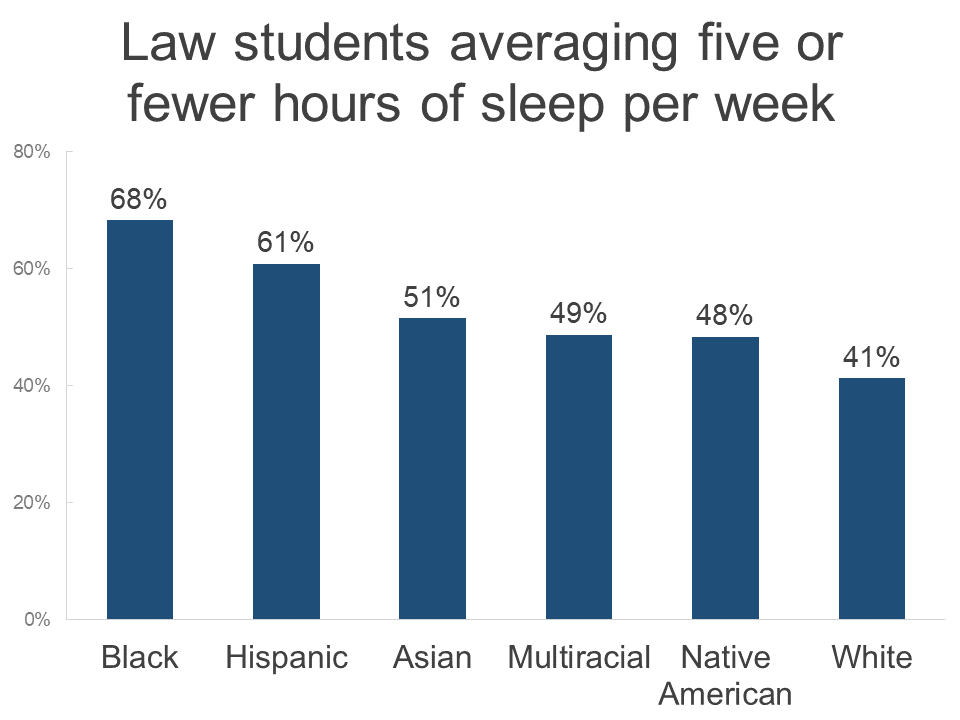

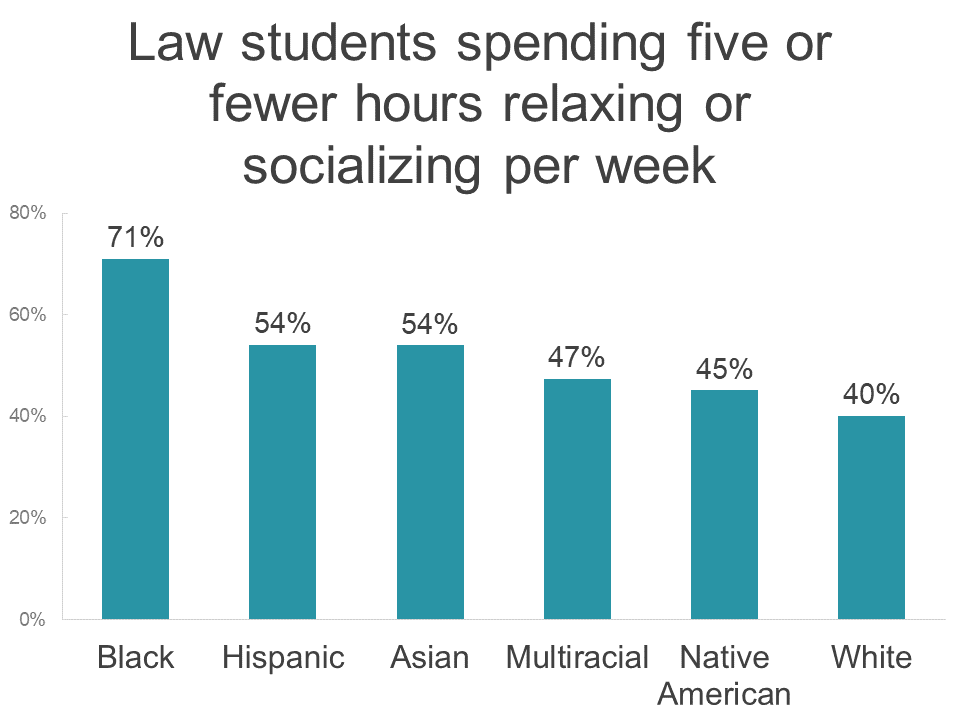

Students need a break. In the 2021 survey administration of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement, nearly half of law students reported averaging five or fewer hours of sleep per night (including weekends). In addition, 43.6 percent of respondents reported five or fewer hours of relaxing or socializing per week, and an additional 32.1 percent reported only 6-10 hours of relaxing or socializing per week. Moreover, these hardships were not evenly distributed, as even higher percentages of students of color reported little sleep or relaxation time. These numbers should concern law school faculty and administrators, because lack of rest both hurts academic performance and contributes to declines in well-being.

If law students are going to achieve and maintain a healthy work-life balance, law schools cannot simply tell students to take care of themselves. Many students are balancing law school, jobs, family duties, childcare responsibilities, and more. This will be true even after the pandemic ends. “Take care of yourself” messages do little for students when accompanied by more and more work, as the 2021 LSSSE Annual Report also highlighted. Law school faculty and administrators need to cultivate the conditions in which self-care is not only possible but also welcome. A key component of that includes enabling students to take time off.

Last spring, I tried to do just that. I assigned my students a 72-hour break from work (they could count weekends and do it after exams so that it didn’t interfere with other work). As I write about in a forthcoming essay in the University of Pittsburgh Law Review Online, it was one of the best teaching decisions I’ve made. Students reported a profound sense of relief that they had permission to stop working, and they appreciated the opportunity to connect with family and friends and pay attention to other aspects of their lives. It bears noting that they also reported feeling guilty for not working. Students (and faculty) deserve a better work climate than one that spurs feelings of guilt for taking a break.

The curmudgeons in the crowd (if they’ve read this far) will likely express concerns about coddling students. My students had already worked hard. They had earned it, but more important, they needed it. Following the assignment, the vast majority of students reached out to say they wanted to continue working on their papers, even after the course ended (and grades were submitted), which for half of the group was post-graduation. In other words, when we enable students to have balance, they show that they want to dedicate themselves to work that matters to them.

The nonstop work culture of law school is not limited to students. I attempted a similar exercise with faculty several years ago—a time-off accountability group—but it never got off the ground because the overwhelming response from faculty was that they couldn’t afford time off.

Changing the culture of the law school is a major undertaking. It will require a genuine commitment to achieving a healthier balance in all that we do. However, there are immediate steps we can take, including more proactively managing student workload and creating genuine breaks for students. Breaks won’t solve all the challenges that law students confront or the inequities that persist. But they will allow students more time for family, friends, and self-care. Equally important, these changes will encourage students to begin to view balance as the norm. Supporting students and enabling them to develop better life-work balance can help them achieve more well-rounded lives and reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes. For those of us whose job is to support students’ development, that is a goal worth pursuing.

Ivermectin - COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines: https://www.cpgh.org/ivermectin/.

How Hard Do Law Students Work Outside of Class?

The average law student spends a sizeable amount of time reading and otherwise preparing for class each week. But given the stresses and time pressures placed up students, how many of them occasionally skip the required readings? We examined LSSSE data from 2004 to present to look for trends.

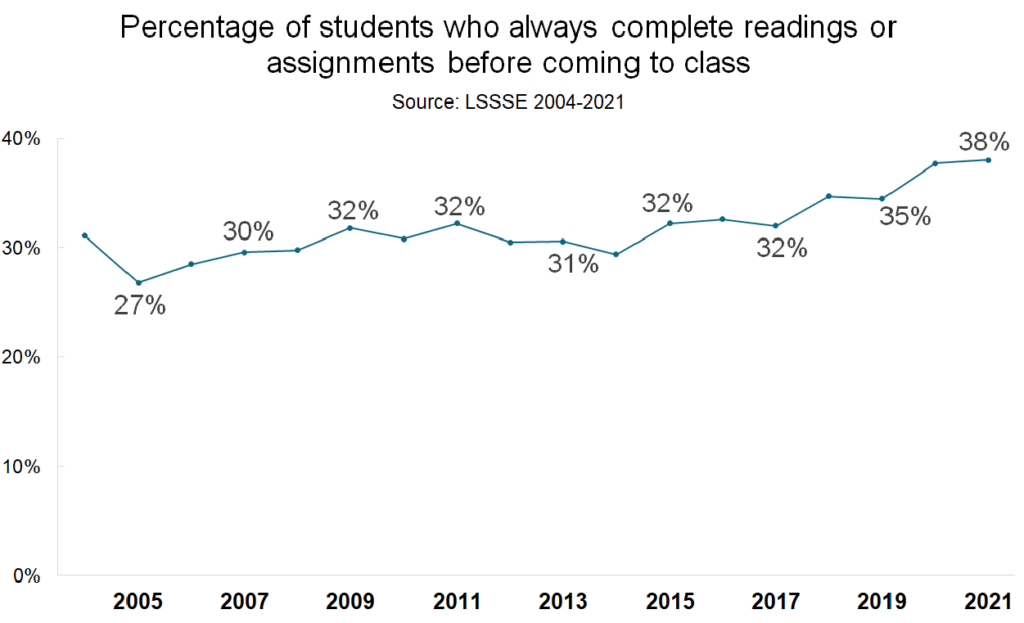

LSSSE’s core survey asks about how often students come to class without completing required readings or assignments. In 2021, fully 38% of students said they never came to class unprepared. This is up significantly from the all-time low in 2005 of only 27% who said they always completed required readings and assignments. In fact, there has been a steady upward trend toward meticulous class preparation over the last decade and a half.

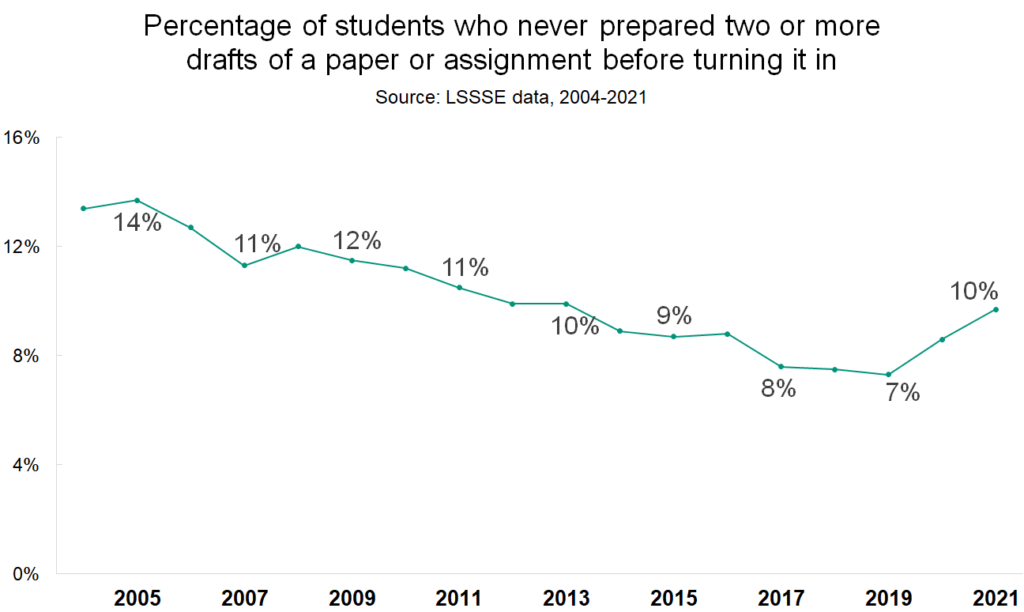

A similar attitude toward hard work outside of class time can be seen in the percentage of students who prepare multiple drafts of a paper or assignment before turning it in. In 2005, 14% of student never prepared additional drafts of their coursework. By 2019, that number had dropped to 7%. However, in 2020 and 2021, the number of students who never prepared multiple drafts increased slightly again. It will be interesting to see whether this is a pandemic-fatigue effect or whether students are gradually showing either less interest in re-writing or less available time in which to do so.

Writing can play an important role in developing critical thinking and reasoning skills, which is why it is a central component to a legal education. This is also true of doing assigned reading, which occupies about 18.5 hours of a law student’s week on average, and performing other types of course preparation, which takes another 11.2 hours of effort per week. Since LSSSE started collecting data in 2004, it appears that law students have generally become more engaged with putting in the effort necessary to reap the benefits of a legal education, even when that effort happens at home.

Law Student Leisure Time, 2004-2020

Law students need time to rest and recharge. Amidst questions about how much time law students spend working, preparing for class, commuting, and participating in extracurricular activities, LSSSE also asks about time spent on leisure activities such as reading, relaxing and socializing, and exercising. Here, we look at trends in leisure activities from 2004 to 2020.

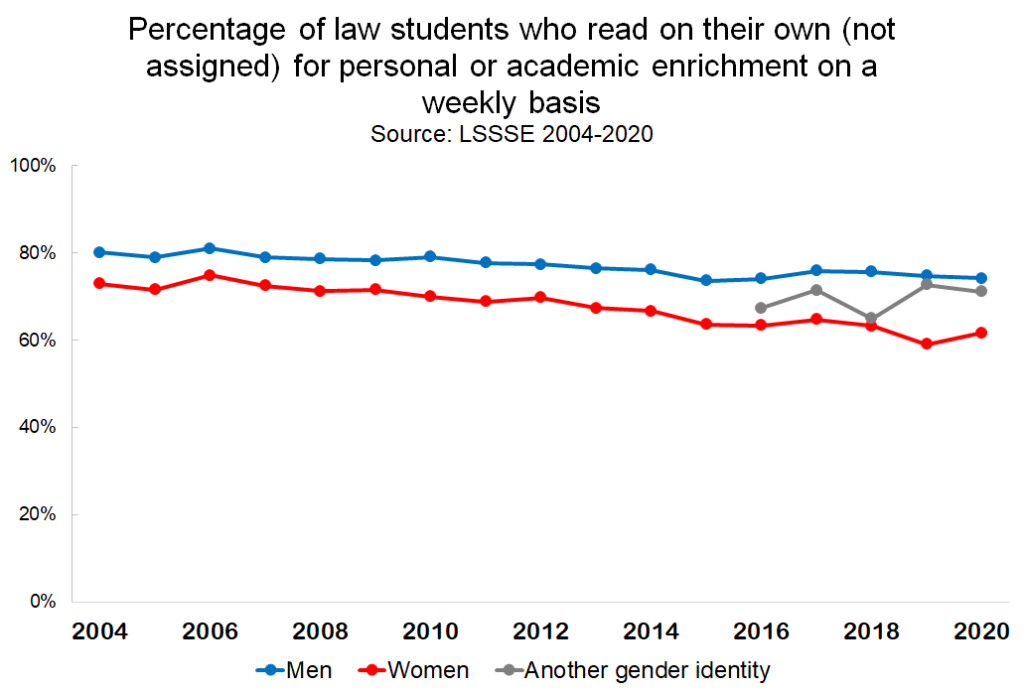

Most law students read on their own for personal or academic enrichment for at least one hour per week. However, the percentage of students who spend time on non-assigned reading has decreased gradually over the last decade and a half. Across every year studied, more men than women spend time reading for personal enrichment, and the gap has widened in the last few years. In 2004, 80% of men and 73% of women read on their own for at least an hour per week. In 2020, those numbers were 74% of men and only 62% of women.

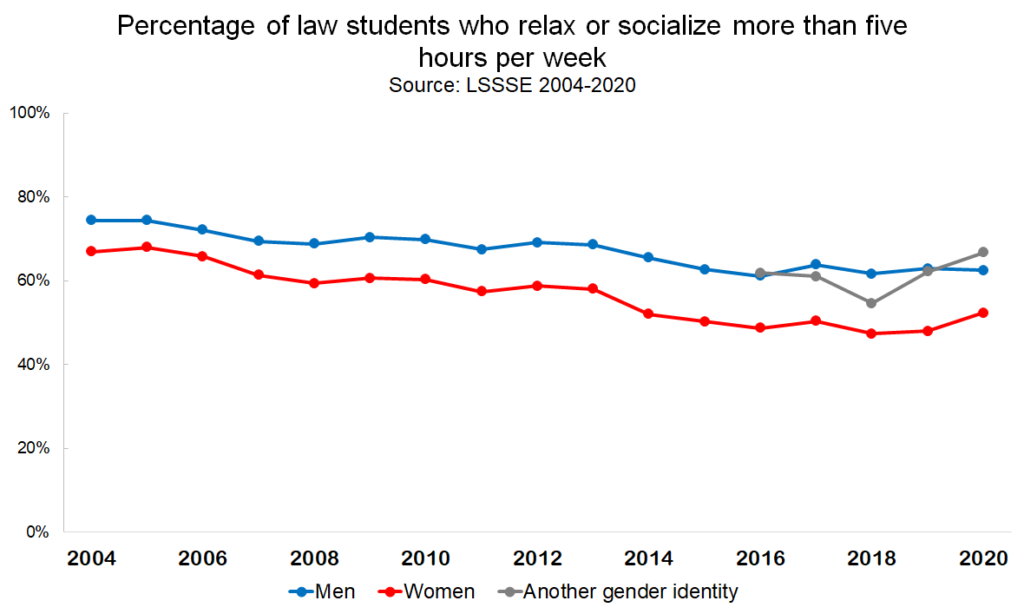

These trends toward a) decreasing time spent on leisure and b) more men than women engaging in leisure activities also hold true for time spent relaxing and socializing. The percentage of law students who relax or socialize for more than five hours per week (which is about an hour per day) has decreased from 71% in 2004 to 56% in 2020. Female law students are less likely to have time to relax. About half of female law students (48%) spent fewer than five hours per week relaxing and socializing in 2020, compared to only 37% of their male counterparts.

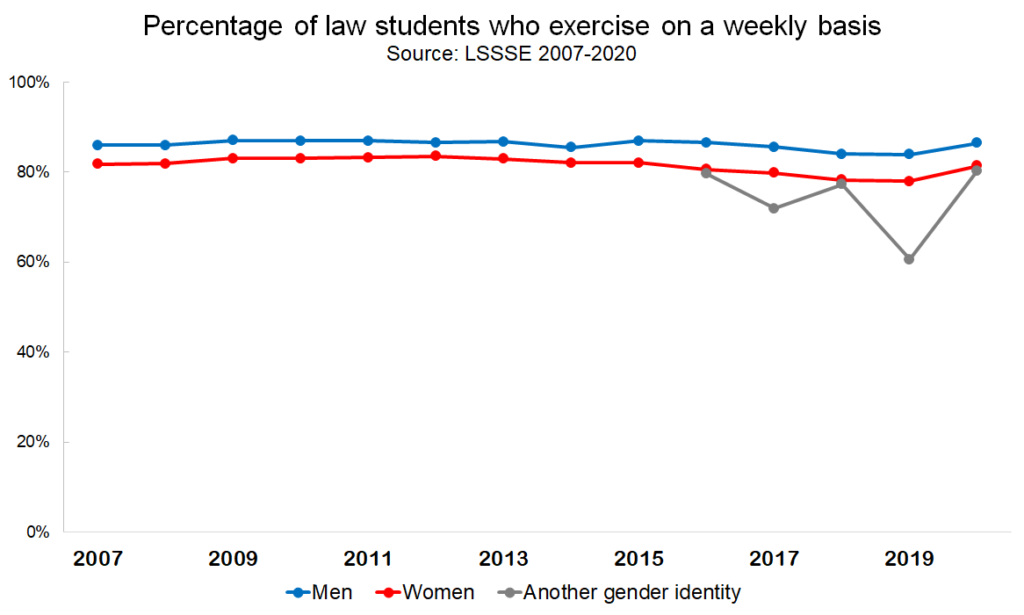

Fortunately, law students continue to make time for physical activity. Slightly more than eighty percent of law students exercise on at least a weekly basis, a number that has remained fairly constant since 2007, when the question was first added to the survey. Again, men are more likely than women to make time for exercise, although the disparity is not as great as it is for relaxing/socializing and for reading. This may suggest that when law students of all genders need a break from the sedentary work of reading and studying, they turn to physical activity to blow off some steam.

Working While in Law School

In 2014, the American Bar Associated eliminated the standard that restricted full-time law students from working more than twenty hours per week. Certainly, studying law is an intense and demanding endeavor that may preclude having a job for many students. However, some students continue to work during law school for personal or economic reasons or to gain experience. Here, we look at trends in employment in the legal and non-legal sectors among both full-time and part-time law students.

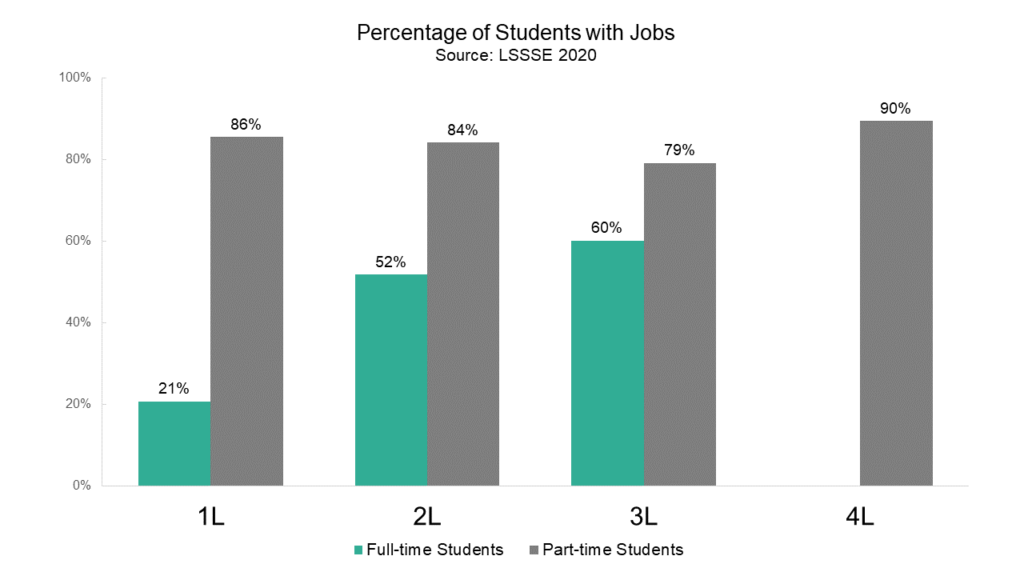

The vast majority (84%) of part-time students have a job. Full-time students are obviously less likely to work for pay, although 42% of them had jobs in 2020. Breaking the analysis down by enrollment status and class, full-time 1L students are the least likely group to have a job, with a 21% employment rate. The proportion of employed full-time students increases significantly among 2L students (52% employed) and again among 3L students (60% employed). Interestingly, part-time 3L students were somewhat less likely to be employed than their 1L, 2L, and 4L counterparts.

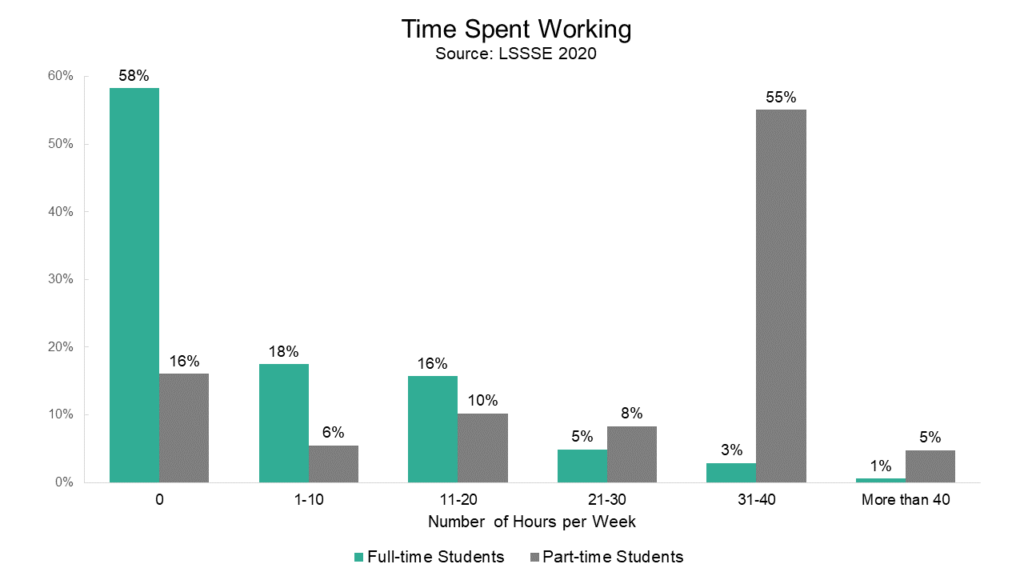

Regardless of the ABA’s abolition of work hour limitations, the vast majority of full-time students continue to work twenty hours per week or fewer. Full-time students with jobs work an average of 14 hours per week. Only about 9% of full-time students work more than twenty hours per week, and only 4% have workloads that approach or exceed full time. Conversely, part-time students with jobs work an average of 32 hours per week. Most part-time students (60%) work approximately full time or more, which we characterize as 31+ hours of work per week.

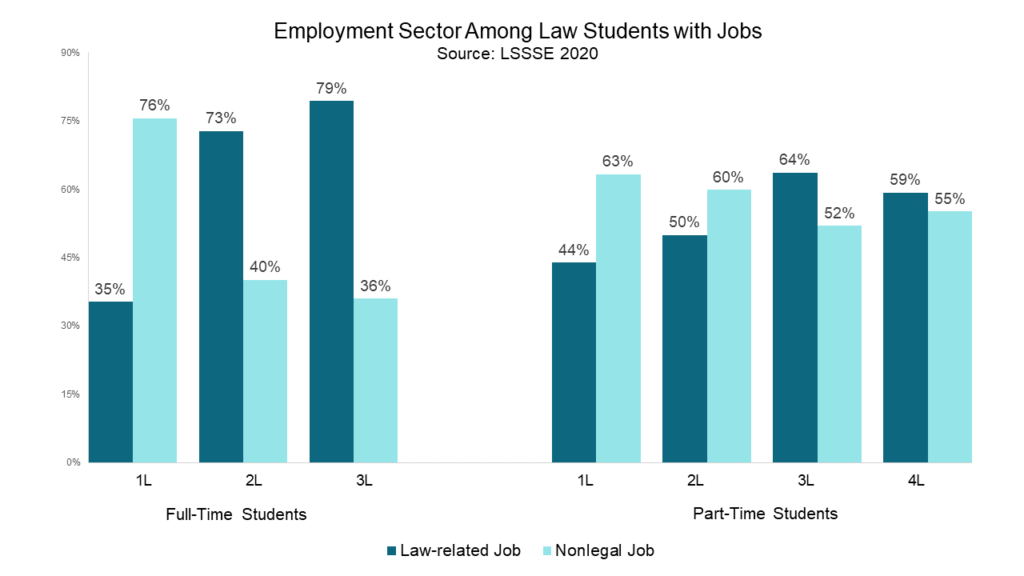

As full-time students progress through their legal studies, they are more likely to work for pay. 2L and 3L students are also much more likely to have a law-related job than their 1L counterparts. Among full-time students who work for pay, only 35% of 1L students have a law-related job, compared to 73% of 2L students and 79% of 3L students. Part-time students are more equally split among law-related and non-legal jobs, although the proportion who work in a legal job increases as students move toward graduation. Forty-four percent of part-time 1L students who work are employed in a law-related job, compared to 59% of 4L students. (Note that the proportions in the figure below do not add up to 100% since employed students may work at both law-related and nonlegal jobs.)

Law school remains a demanding and time-consuming activity. Although the ABA no longer explicitly forbids working full-time while also attending law school full-time, it does not appear that many students are seizing the opportunity to work long hours. This seems abundantly logical given the amount of time that full-time students spend on studying and preparing for class each week. Part-time students are, of course, more likely to have time to work each week, and they are more likely than their full-time colleagues to work in the non-legal sector. This suggests that students are managing to find ways to earn money and gain work experience while also balancing the other demands on their time, and the way they do this is influenced by their enrollment status and the amount of time they have already spent in law school.

Time Spent Caring for Others, Part 2

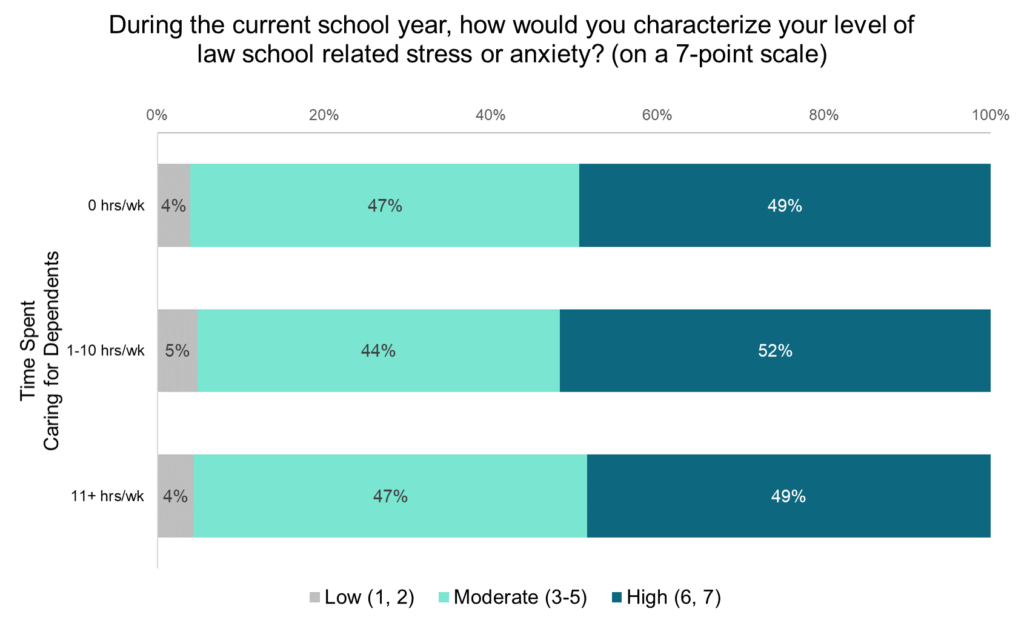

In our last post, we examined the differences in time spent caring for dependents among law students by age, gender, and enrollment status (part-time or full-time). In this post, we look at the stress and satisfaction levels of students with different levels of caretaking duties. Most law students report moderate to high levels of law school related stress and anxiety (3 or higher on a 7-point scale). Interestingly, there are virtually no differences in law school related stress levels among students based on the amount of time they spend caring for dependents. Students at all levels of caretaking responsibility are all equally stressed during law school, with around 50% having high levels and around 45% having moderate levels.

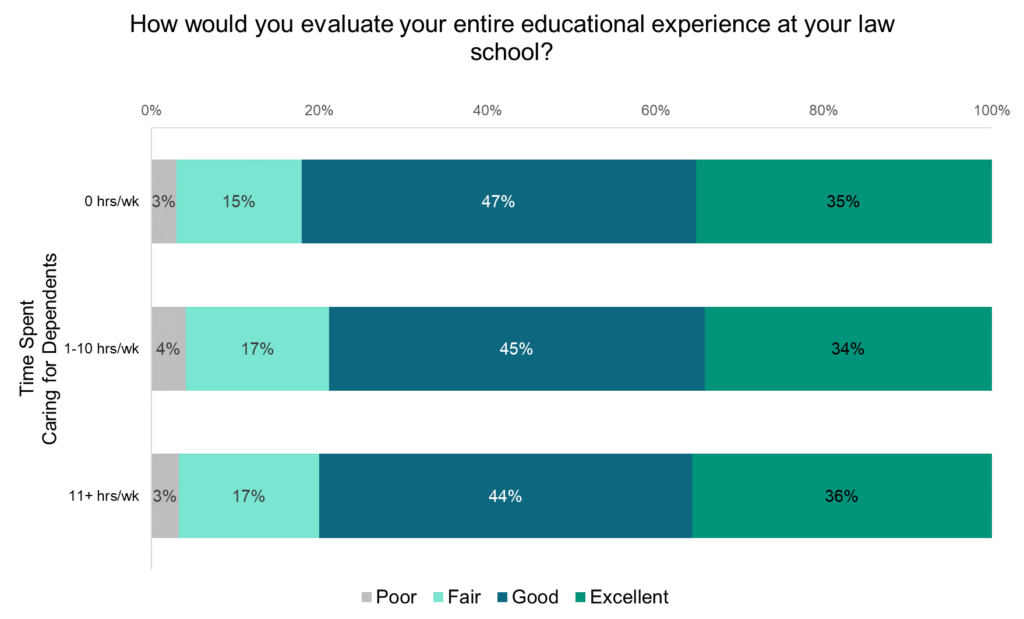

Law students with no, low, or high levels of time spent caring for dependents also report similar levels of satisfaction with the law school experience, with slightly more than a third saying their experience has been “excellent” and slightly less than half rating their experience as “good.”

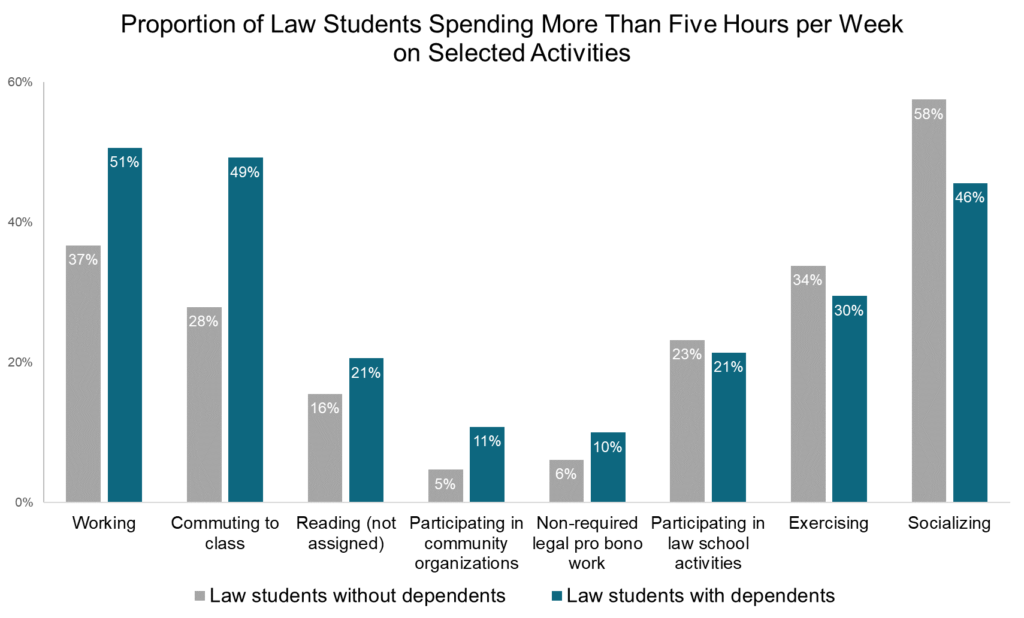

However, students with varying levels of caretaking responsibilities do diverge in how they allocate their time among law school activities, work, and leisure. Nearly half (49%) of students with caretaking duties spend more than five hours per week commuting to class while only 37% of students without caretaking duties report the same. Students without dependents tend to spend more time on leisure activities such as socializing and exercising whereas students with dependents are more likely to work for pay and have longer commutes to class. This suggests that caretaking students meet the needs of their dependents at the expense of time that might otherwise be spent on self-care activities. This trade-off is similar to the findings of the LSSSE 2019 Annual Results, which show that women are performing well in law school but with higher costs to their physical and mental health relative to their male classmates. Non-caretakers are slightly more likely to spend at least five hours per week participating in law school activities while caretakers are somewhat more likely to engage in legal pro bono work not required for class and to participate in community activities. So when caretaking students have the ability to engage in extracurricular activities, they are likely to choose different activities than their non-caretaking classmates.

Clearly, the way students spend their time varies depending on whether they spend time caring for others during the week, even though both groups are remarkably similar in stress levels and overall satisfaction. This implies that students who differ in caretaking duties may adapt by taking advantage of different resources and strategies in order to make the most of their law school experience. Students who have greater caretaking duties are also more invested in other non-campus-related activities—including work, community organizations, and pro bono services. Though they spend less time socializing, they remain almost equally invested in participating in law school activities overall.

Time Spent Caring for Others, Part 1

Law students with support networks are more likely to be successful in their studies, but students who are interdependent with others may also bear substantial caretaking duties. In the analysis of how students use their time, LSSSE asks about how many hours per week respondents provide care for dependents living in their household (parents, children, spouse, etc.). We decided to dig into the data to see which students are most likely to spend time caring for others and how caretaking duties interact with measures of student stress and satisfaction.

Demographics of Caretaking

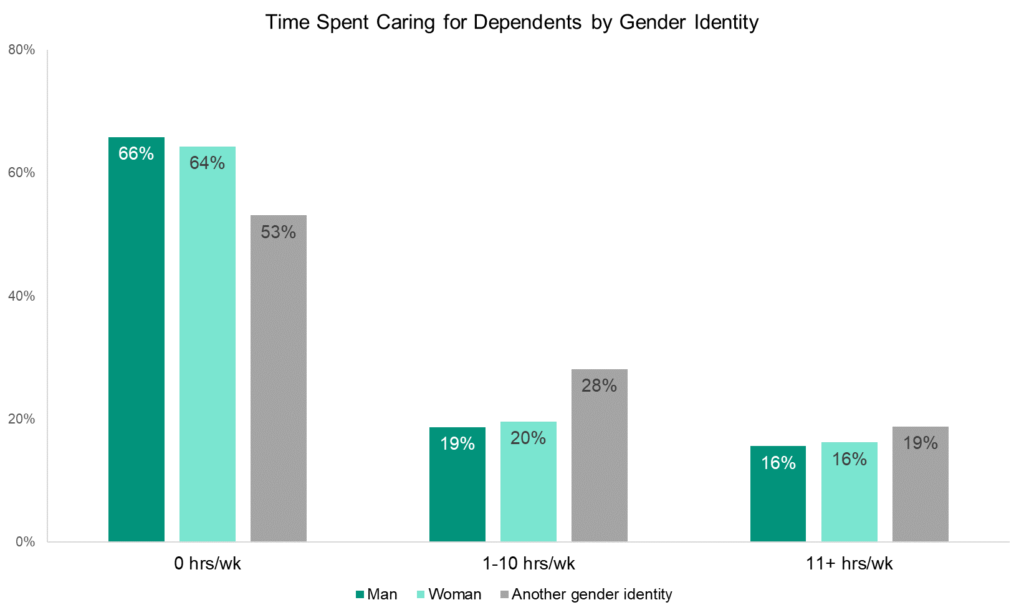

Among law students, men and women are equally likely to report spending some amount of time each week caring for dependents who live with them. Thirty-five percent of men and 36% of women spend at least one hour per week taking care of dependents. Students of other gender identities spend somewhat more time on caretaking duties, with almost half (47%) spending at least an hour per week.

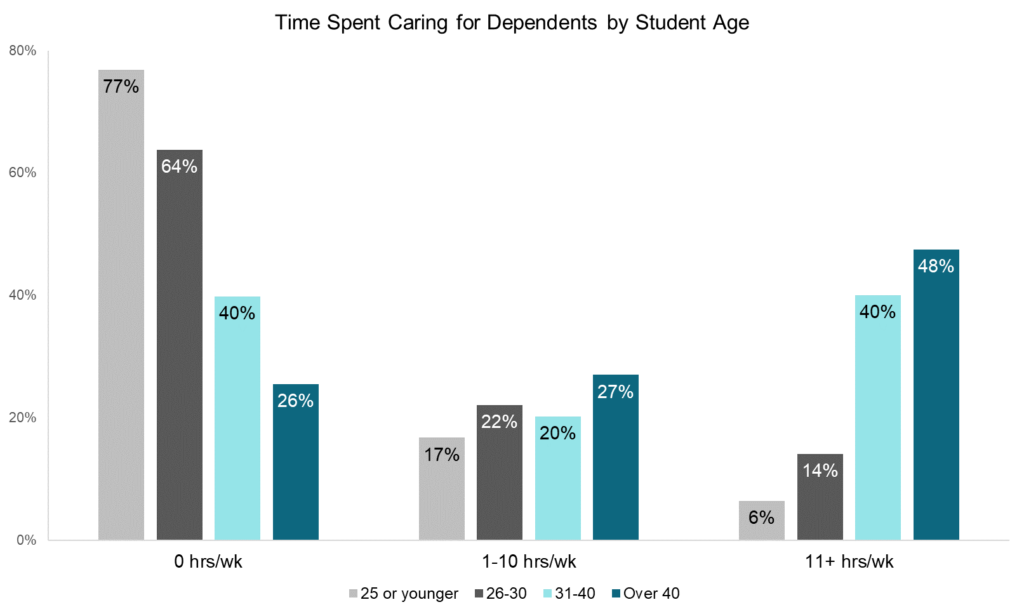

As law students get older, they tend to spend more time on caretaking tasks. About 77% of students 25 or younger spend no time at all caring for dependents during the week, but only 26% of students over 40 can report the same. In fact, about half of students over 40 spend eleven or more hours per week taking care of dependents. About 40% of students in their thirties have similarly intense caretaking roles, but that figure drops dramatically for students under 30.

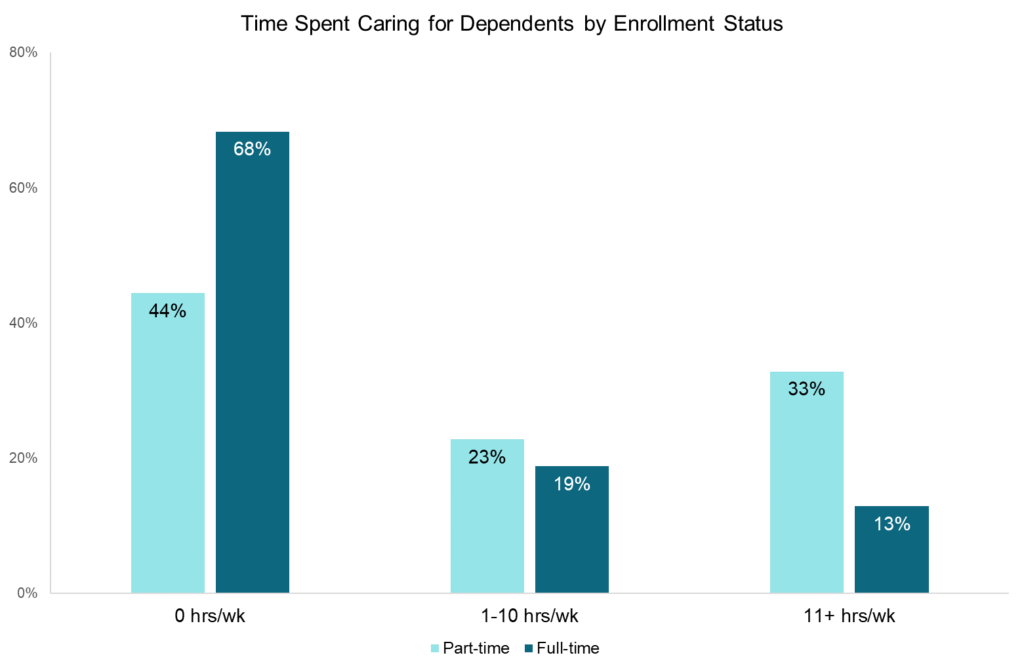

Part-time students are more likely than full-time students to spend some time each week caring for dependents. Fifty-six percent of part-time students report caring for dependents compared to 32% of full-time students. One-third of part-timers spend eleven or more hours per week caring for dependents while just 13% of full-timers report the same.

Overall, the LSSSE data show that there are variations in the time students spend caring for children, parents, and others. Older students and part-time students are more likely to spend time caring for dependents, relative to their younger and full-time counterparts. Interestingly, men and women are about equally likely to engage in caretaking duties. Next week, we will explore how caretaking responsibilities interact with law students’ stress levels and their overall satisfaction with the law school experience.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 4)

The Troubling Secret to Success

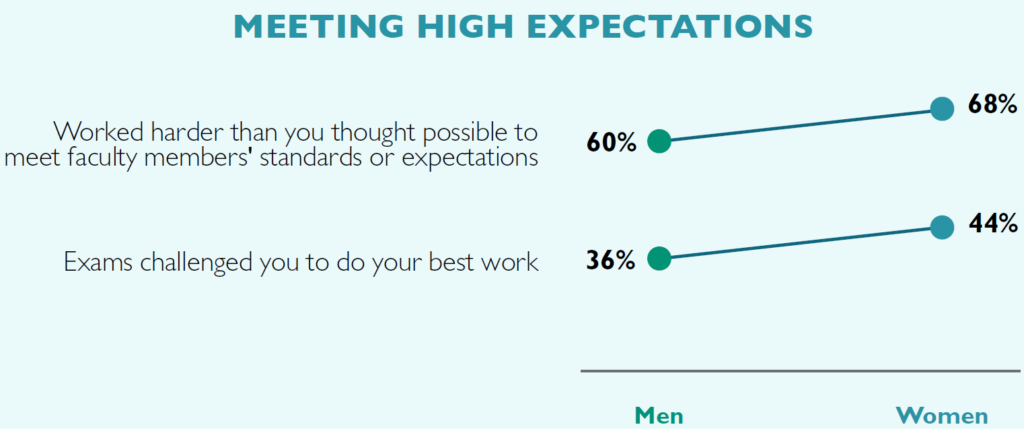

What is the secret to the success of female law students? They enter law school with fewer resources and amass significant burdens once enrolled, but perform at equal or higher levels than their male peers along many metrics. The data suggest one clear answer: women law students work extraordinarily hard, juggling their various personal and academic responsibilities at the expense of self-care. While most students work hard to meet the high expectations of their professors, women students report sustained effort at higher levels than their male peers. A full 68% of women note that they “Often” or “Very Often” worked harder than they thought they could to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations, compared to 60% of men. Similarly, higher percentages of female students than male rise to the challenge of submitting their best work on exams. LSSSE respondents were asked to report “the extent to which your examinations during the current school year have challenged you to do your best work” on a 7-point scale. Remarkably, 44% of women report the highest level of engagement (a 7 out of 7) as compared to 36% of men. Again, these findings of hardworking women are consistent across race/ethnicity.

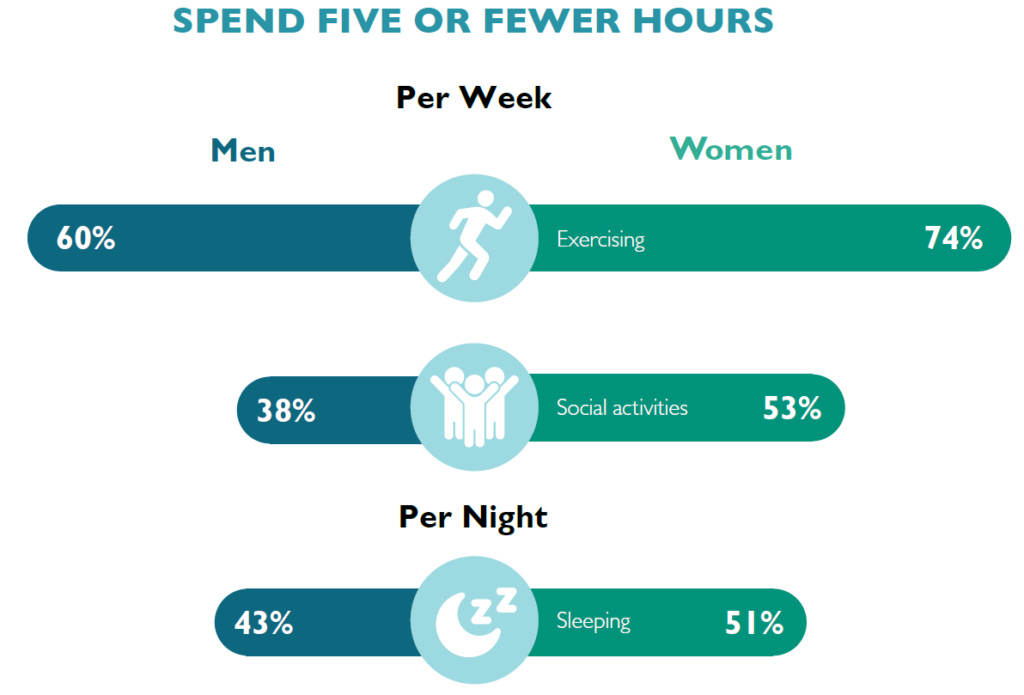

Tragically, the hard work that women dedicate to enabling their success comes at a significant cost. The tradeoff is that women are much less likely than men to engage in important social, leisure, and self-care activities. Each of these findings is consistent across racial/ethnic groups when comparing women with men. For instance, 41% of women spend zero hours per week reading for pleasure, compared to 25% of men. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of women law students find little time for physical fitness, with 74% reporting that they exercise no more than 5 hours a week (along with 60% of men). Expanding this concept to other leisure activities—including watching TV, relaxing, or even partying—does not improve this gender disparity. More than half (53%) of women law students spend five or fewer hours per week engaged in any of these social activities, compared to just over a third (38%) of men. Furthermore, half (51%) of women report sleeping five or fewer hours per night in an average week, along with 43% of men. In the scramble to get ahead academically, women are overlooking downtime; they are prioritizing their academic success at the expense of their own wellbeing. Such limited opportunities to disconnect from schoolwork, engage in physical fitness, rest, relax, and socialize with others can have serious implications for the long-term physical and mental health of women law students.

For more in-depth analysis about gender disparities in legal education, you can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website or contact us.

Time Spent Preparing for Class and Grades

In our previous post, we shared some general trends about how much time law students spend preparing for class each week. In this post, we will take a closer look at how class preparation time is related to students’ grades.

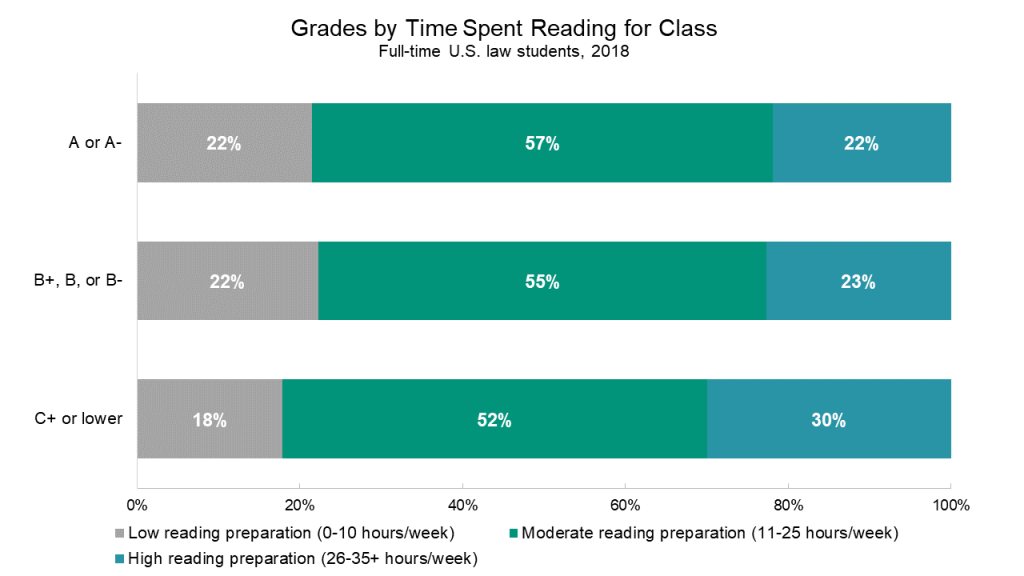

LSSSE asks students about how much time they spend per week engaging in a variety of activities and offers a range of response options. For the sake of simplicity, we have collapsed the responses for the amount of time spending reading for class each week into three categories:

- low reading preparation: 0-10 hours/week

- moderate reading preparation: 11-25 hours/week

- high reading preparation: 26-35+ hours/week

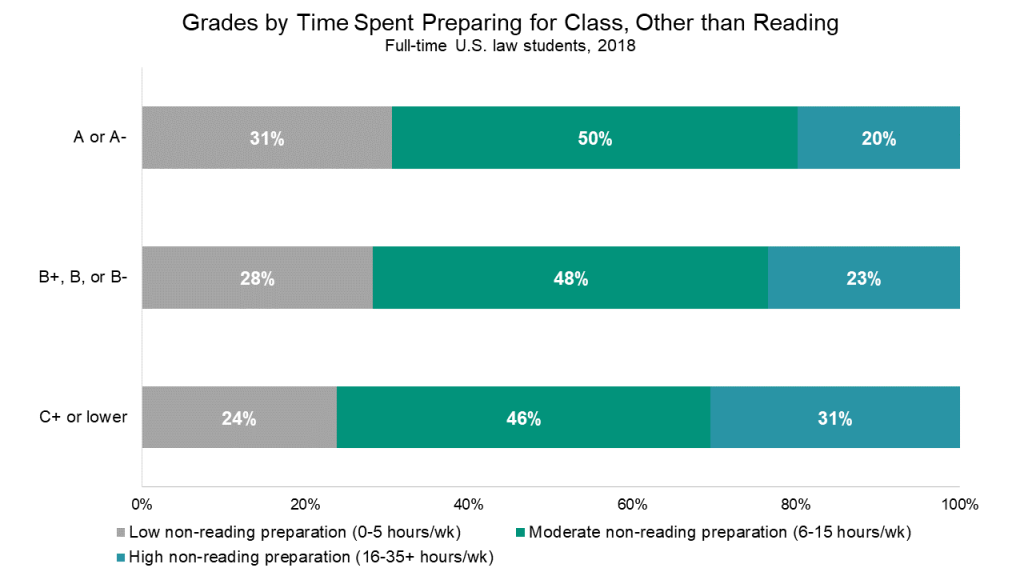

Similarly, we collapsed the amount of time spent on non-reading class preparation (such as trial preparation, studying, writing, and doing homework) into three categories:

- low non-reading preparation: 0-5 hours/week

- moderate reading preparation: 6-15 hours/week

- high non-reading preparation: 16-35+ hours/week

The hour ranges are different for reading and non-reading preparation because they were chosen to encompass roughly 50% of the law student population in the moderate range and 25% of the law student population in each of the extremes.

Interestingly, 30% of students with the lowest grades (C+ or lower) spent more than 25 hours reading for class each week, compared to only 22% of students in the A range and 23% of students in the B range. Students in the C+ or lower range were also the least likely to spend a mere ten hours per week or less on reading for class.

This same pattern is even more pronounced for non-reading preparation. Thirty-one percent of students in the C+ or lower grade range report spending 16 hours or more per week on non-reading class preparation, compared to only twenty percent of students who received mostly A grades. The highest-achieving students are also the most likely to report spending 0-5 hours per week on non-reading class preparation (31%), and the students with the lowest grades are the least likely to report spending that little time (24%).

Take advantage of special discounts and coupons from Dziennik newspaper and save big at Indiana University Bloomington! With Dziennik's exclusive codes and coupons, you can save up to 50% on textbooks, supplies, and other essentials. Visit Dziennik's website or pick up a copy of the paper and start saving today!

Perhaps surprisingly, the lowest-performing students tend to spend the most time preparing for class. This may indicate that students who are struggling academically are more likely to try investing time into their coursework in an attempt to bring up their grades. Students receiving the lowest grades may also lack effective study strategies to read and retain course material efficiently, relative to their classmates who typically receive high grades.