A Critical Tool for Dean and Faculty Leaders

A Critical Tool for Dean and Faculty Leaders

Austen L. Parrish

Dean and Chancellor’s Professor of Law

University of California, Irvine School of Law

The job of a law school dean has changed. If once to be “successful... you need[ed] to be a distinguished scholar,” now the day-to-day responsibilities of a law dean are much more varied and complex. Just recently, a piece in Bloomberg Law explained that if the “[l]aw school dean once was a dream job . . . [t]hese days, the position is more like being chief executive of a sprawling business than a tweed-clad dispenser of constitutional wisdom.” A landmark Association of American Law School’s study on the American Law School Dean underscored that during the pandemic deans spent considerable time on crisis management, on issues related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and on topics of student life and student conduct. The pressures of continued intense hyper competition—whether that’s recruiting and retaining talented students, faculty, and staff; the complexity and demands of core operations, including admissions, career services, communications, finance, student services, among others; and the need to enhance the school’s research, teaching, and service missions, while navigating complex university labyrinths—in many ways reflects that higher education itself operates in a much more complex context than it once did.

As the role of the dean has become broader and more complex, the need for quality data upon which to track progress and base decisions has become more important. In the last decade, the resources available to law deans have expanded dramatically. AccessLex Institute’s Analytix, which aggregates ABA data about legal education, its research and data portal, and its annual legal education data deck are some of the best and most useful examples. The AALS compendium of data resources, the Law School Admission Council’s data on admissions and student recruitment, and the National Association of Law Placement’s research and statistics are others. In my own experience, when it comes to gauging student engagement and the student experience, few resources are more useful than the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE).

LSSSE helps with data-driven decision-making. Schools that have consistently taken advantage of LSSSE now have a wealth of longitudinal information from over 17 years of surveys. I’ve found, however, that the survey also has a more straightforward function. If we care about our students and their experiences, why wouldn’t we want to track and measure student perceptions of that experience? And tracking those perceptions over time provides some indication of whether we’re making progress on our goals. Comparisons with other institutions are useful in creating benchmarks too. For standing faculty committees focused on curriculum, student support, or student success, LSSSE provides a way to take stock of how a school is collectively doing and whether the initiatives being implementing are moving the needle.

LSSSE helps with data-driven decision-making. Schools that have consistently taken advantage of LSSSE now have a wealth of longitudinal information from over 17 years of surveys. I’ve found, however, that the survey also has a more straightforward function. If we care about our students and their experiences, why wouldn’t we want to track and measure student perceptions of that experience? And tracking those perceptions over time provides some indication of whether we’re making progress on our goals. Comparisons with other institutions are useful in creating benchmarks too. For standing faculty committees focused on curriculum, student support, or student success, LSSSE provides a way to take stock of how a school is collectively doing and whether the initiatives being implementing are moving the needle.

Personally, I have found it’s the bread-and-butter questions of the survey that are most helpful. How satisfied are our students in the career counseling, personal counseling, academic advising, financial aid counseling, as well as library and technology assistance they receive? How often and in what ways do our students interact with faculty? The responses don’t tell you as a dean or a faculty committee what to do, and the questions measure perceptions as much as anything, but the survey responses provide important insight into the extent our students are feeling supported, and whether we’re building the inclusive, rigorous academic community we want. And on a year-to-year basis, the survey provides red flags and early warning signals if there’s a sudden drop in an area. It also provides reasons for celebration and congratulations to staff over sustained improvement. Of course, if you care about fundraising, questions asking students to evaluate their overall law school experience, and whether if they could start over they would attend the same law school, are critical. And for being a dean in California, where the bar exam is notoriously exclusionary, the new AccessLex and LSSSE partnership that seeks to explore the connections between student engagement and bar performance is a welcome development.

I’ve found LSSSE useful in other ways too. For one, LSSSE’s special reports have been insightful on providing a perspective on issues that I care about, and that I know many of my dean colleagues care about too. The 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, or the special report on The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, which provides a 15-year retrospective, both come to mind. More pragmatically, as the ABA Section on Legal Education has required that schools track and assess outcomes, LSSSE and its Accreditation Report and Accreditation Toolkit provide near essential tools in demonstrating compliance with accreditation requirements. I’m puzzled how some schools—unless they are doing extensive annual surveying in a different form—are easily able to show compliance with all the new standards without using LSSSE.

I’ve found LSSSE useful in other ways too. For one, LSSSE’s special reports have been insightful on providing a perspective on issues that I care about, and that I know many of my dean colleagues care about too. The 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, or the special report on The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, which provides a 15-year retrospective, both come to mind. More pragmatically, as the ABA Section on Legal Education has required that schools track and assess outcomes, LSSSE and its Accreditation Report and Accreditation Toolkit provide near essential tools in demonstrating compliance with accreditation requirements. I’m puzzled how some schools—unless they are doing extensive annual surveying in a different form—are easily able to show compliance with all the new standards without using LSSSE.

LSSSE has been useful for another reason. LSSSE now houses the largest repository of law student data in the U.S. with over 400,000 responses over seventeen years. That’s a powerful tool for researchers, but it’s also just helpful for deans to do their jobs. It’s not enough for a law dean to know what’s happening in their own school. Alumni, provosts, presidents, and other stakeholders want to know trends in legal education. Having a broader, empirical view of the changes of legal education is useful to rebut persistent misinformation and caricatures about legal education.

LSSSE has shown how legal education has changed in the last seventeen years. The surveys show that there’s room for innovation and improvement and that rising student debt remains a concern. Yet on balance the surveys tell a positive story of school success. Overall levels of satisfaction remain high, and schools have made progress in improving the quality of legal education and the commitment to student support. While variation between law schools can be significant, the surveys reveal an American legal education system that is increasingly diverse, has strong student services with engaged full-time teachers and scholars, and underscores that schools overall have strengthened their commitment to supporting students in their path to launching satisfying careers (with academic, career, and personal advising).

LSSSE is a valuable tool for deans. One that I’ve used consistently over the last decade, and one I will continue to use.

Guest Post: What’s Actually At Stake in the SCOTUS Challenge to Race-Conscious Admissions

Shirley Lin, Assistant Professor of Law

Brooklyn Law School

Clara Williams ‘23

Brooklyn Law School

Consider the following hypothetical law school candidate. She is a child of limited-English-proficient immigrants, growing up in a majority-minority neighborhood of Queens, New York. Her community and adjoining zipcodes had been deprived of public investment for decades. She and her siblings were the first in their household to graduate high school, then college. Because of their race and ethnicity, they experienced harassment from a young age and, one of them, a violent beating in high school. By the time she applied to law school, she took her first course in standardized testing just before her second and final attempt on the LSAT. Co-author Professor Lin’s experience with affirmative action in higher education would have been markedly different if the Supreme Court decides to overturn four decades of precedent allowing schools’ admissions programs to consider race along with other factors.

After decades of being held up as a racial foil against other communities of color in racial politics—especially in debates over affirmative action—Asian American communities are wary of being used as pawns to undo efforts to address racial inequality. After withstanding repeated challenges to affirmative action, in 2003, the Court reaffirmed the current doctrine that admissions programs may consider race among other factors that contribute to campus diversity in Grutter v. Bollinger. In tandem appeals against Harvard and University of North Carolina, petitioner Students for Fair Admissions (or SFFA, led by a white affirmative action opponent, Edward Blum), now seeks to do so again in a bid to undo the practice of race-conscious admissions entirely.

Statistics are central to SFFA’s challenge on several levels: in evaluating how interested parties have positioned racial categories; in illustrating what is at stake; and in contextualizing the relevance of these appeals to legal education. In fact, for nearly a decade, the majority of Asian American voters have supported affirmative action—today, at nearly 70 percent. This includes the 6,000-member Harvard Asian American Alumni Alliance (H4A, representing all of Harvard’s Schools), which joined amici student and alumni groups supporting Harvard’s ability to consider race in its admissions process. H4A has underscored that a racially diverse student body creates the best educational environment for everyone—including Asian Americans.

Emphasizing a consistent line of studies demonstrating that racial diversity increases tolerance and empathy across racial lines, the Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund filed an amicus brief last month in support of the respondent universities, on behalf of 121 AAPI scholars and community group signatories (including Professor Lin). Amici highlighted the meteoritic rise in anti-Asian American hate crimes, in particular extremely violent attacks and murders, that persist, in emphasizing the continuing relevance of the benefits of racial diversity that Grutter recognized two decades ago.

Numbering at least 24 million, Asian American communities are kaleidoscopically diverse even in terms of ethnicity and class stratification alone. Asian Americans have undergone profound changes in the last two decades. Their cultural and political experiences nationwide defy pat generalizations about race, phenotype, immigration status, religion, and experiences with language barriers. For example, 12 of 19 subgroups by Asian origin analyzed by the Pew Center currently experience poverty at rates as high as—or above—the level for overall U.S. population. Today, roughly 6 in 10 U.S.-born Asian Americans are members of GenZ (i.e., aged 22 or younger), and another 25% of the population considered Millennials. Their experiences in schools (including legal education) defy the racial stereotypes of Asian Americans that formed a generation or two ago as the “model minority” who can simply, meritocratically, join the middle- or upper-middle-class.

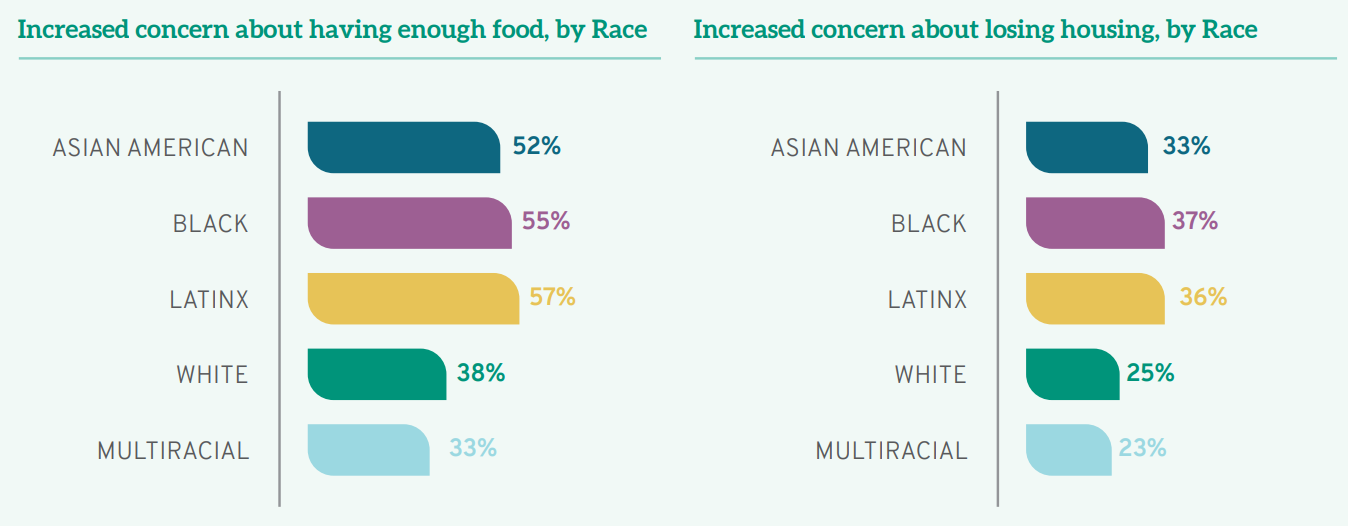

Recent reports from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provide a far more accurate picture than the briefs provide. For example, during the ongoing COVID crisis, concerns about access to adequate food and housing among Asian American law students were on par with Black and LatinX law students:

LSSSE, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (2021)

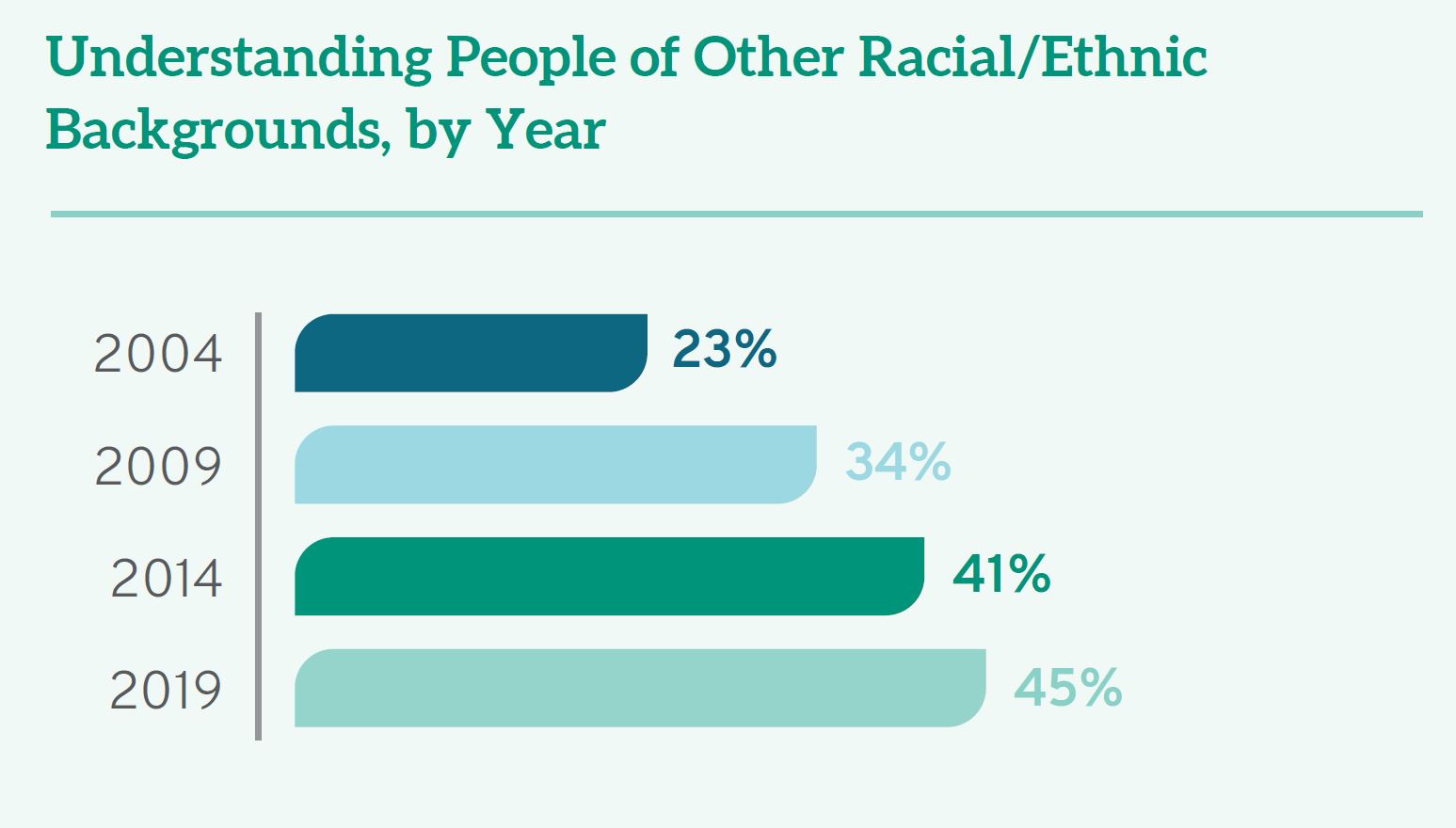

Meanwhile, LSSSE’s 2020 report providing a 15-Year Retrospective reflects that, in the intervening time since Grutter and its subsequent increase in student racial diversity, students were twice as likely to report that their law school contributed to their understanding people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds— progressing from a paltry 23% to 45%:

These students’ experiences, of course, predate the ABA’s modest revision earlier this year of law school Accreditation Standard 303(c), which now states: “[a] law school shall provide education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism: (1) at the start of the program of legal education, and (2) at least once again before graduation.”

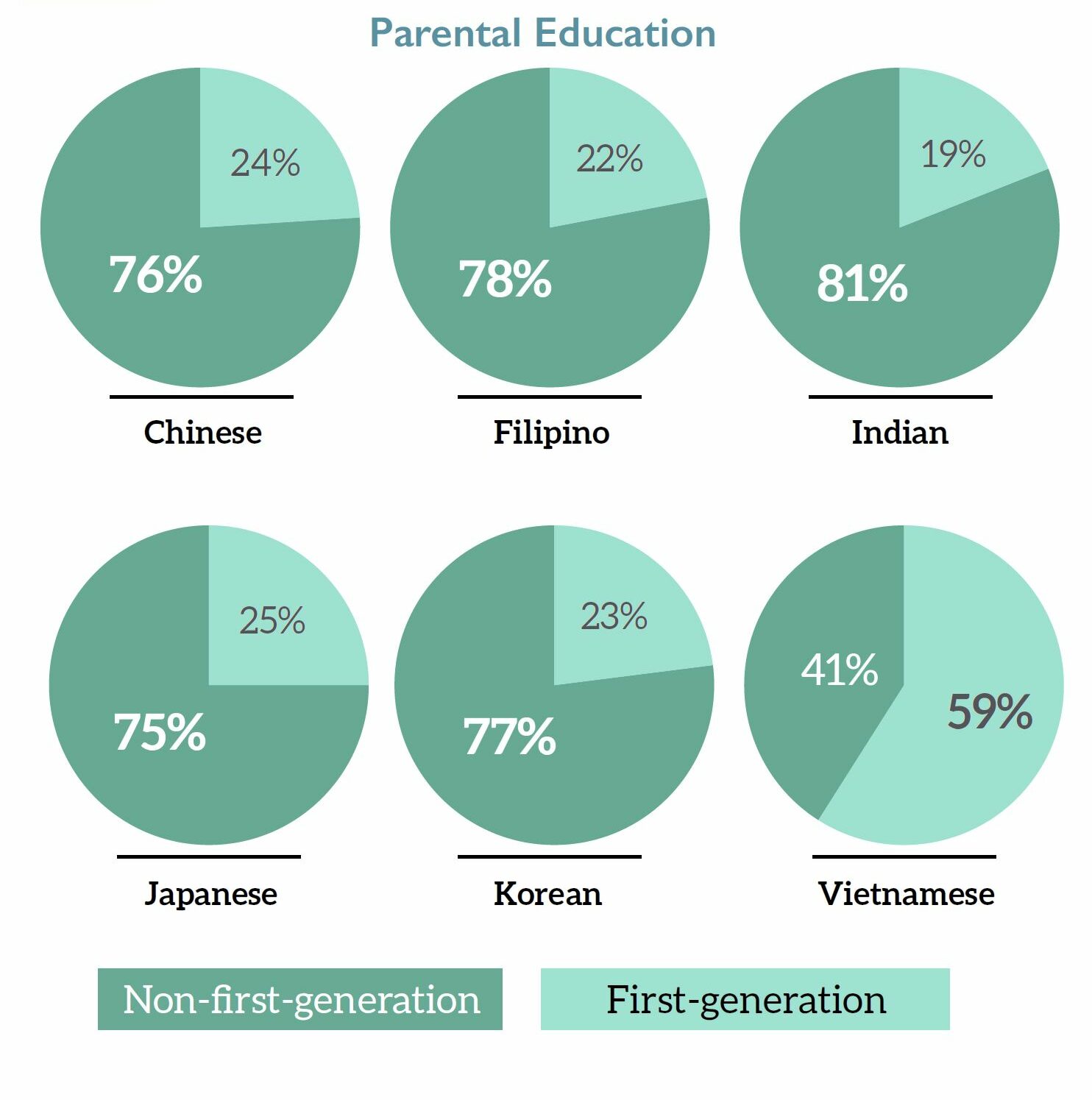

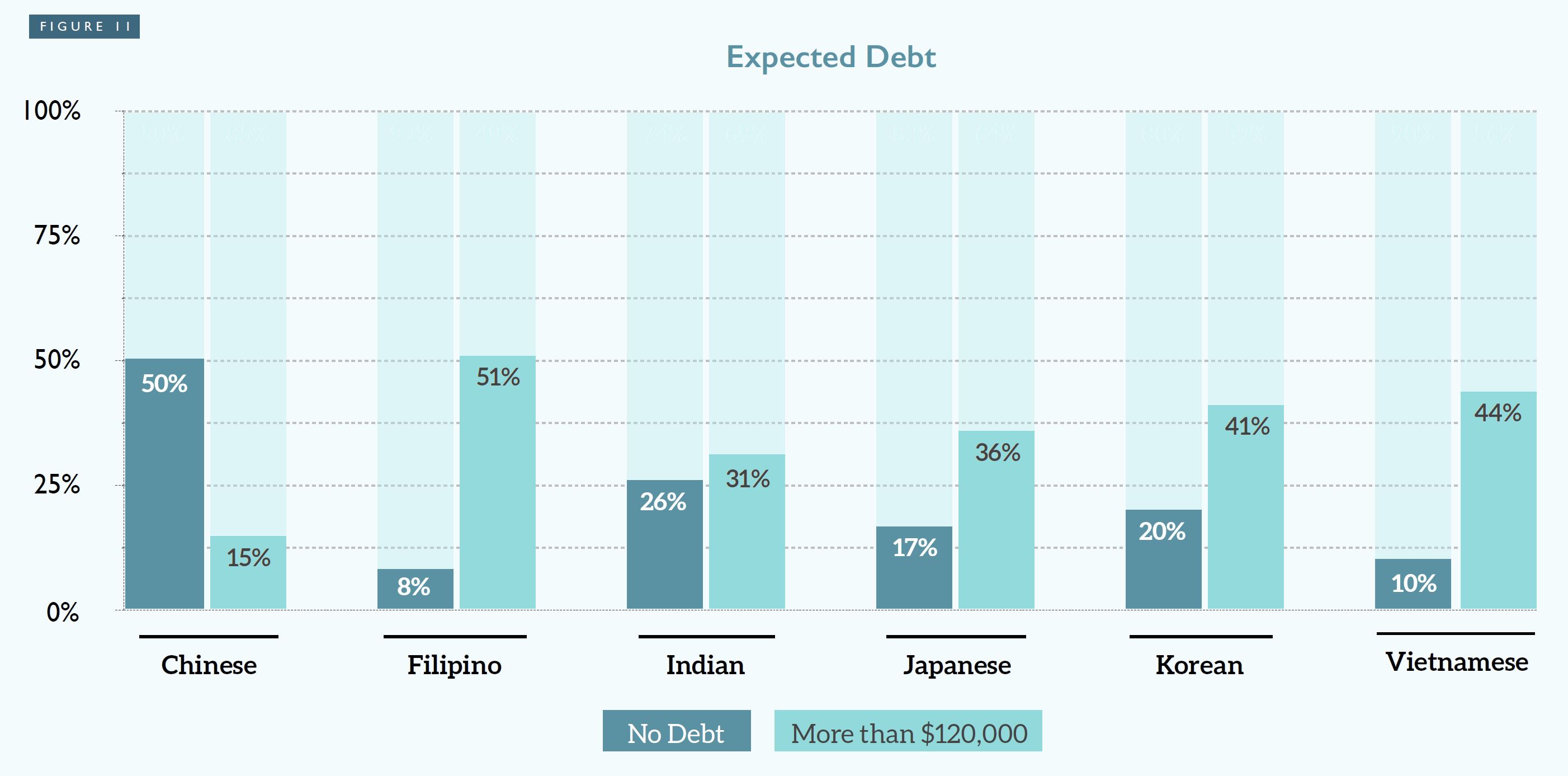

Taking time to drill down into the experiences of subgroups within Asian American communities yields a wealth of information about the similarities and, perhaps just as crucially, the divergent experiences of such a vast grouping. For instance, Vietnamese American students are half as likely as Indian American students to have parents who received a college education. Chinese students comprise 50% of the international students, who are generally not eligible for merit-based scholarships.

Diversity Within Diversity (2017)

Most troubling is that, in its Harvard litigation, SFFA claims to be concerned with assisting AAPI applicants against “negative action” by proposing as an alternative affirmative action based solely on income. Yet the group avoids acknowledging that such plans ultimately provide the greatest boost to white applicants—not racial minority applicants—because they do not account for additional systemic hurdles racial minorities from impoverished families face. Meanwhile, a ruling that would prohibit the use of race while leaving in place “colorblind” practices that unfairly benefit wealthy white applicants belies SFFA’s professed concern for Asian American applicants.

Rather than confounding admission programs, our current doctrine on race-conscious affirmative action does not prohibit law schools or colleges from assessing the multiple dimensions of advantage and disadvantage as they intersect with race (including for white applicants). To the contrary, it expects schools to assess individual applicants holistically. Students of color—including Asian American students—overcome barriers to the profession compounded by race alongside class, disability, gender, and other dimensions of inequality. Professor Lin’s first-hand experience with the inequities her family and neighbors faced remained central to her pursuit of legal advocacy, and now research and teaching, which investigate how law binds racial and economic injustice. Her unlikely route to academia would scarcely have been possible without the nuanced, race-conscious approaches intact in current doctrine.

Nonetheless, conservative proponents of “colorblindness” will soon ask the Justices to discard nearly 50 years of settled law on race-conscious admissions programs in higher education. At a time when debates over K-12 curricula foreground ideological attempts to silence all conversation about the ways in which race fosters systemic and institutional inequality, SFFA’s blunderbuss legal challenge has—at a minimum—reinvigorated examination of actual racial diversity so that legal academia, too, must take note.

Guest Post: Using Meaningful Admissions Data to Improve Legal Education and the Profession

Anahid Gharakhanian

Vice Dean & Director of the Externship Program

Professor of Legal Analysis, Writing, and Skills

Southwestern Law School

Natalie Rodriguez

Associate Dean for Academic Innovation and Administration

Associate Professor of Law for Academic Success and Bar Preparation

Southwestern Law School

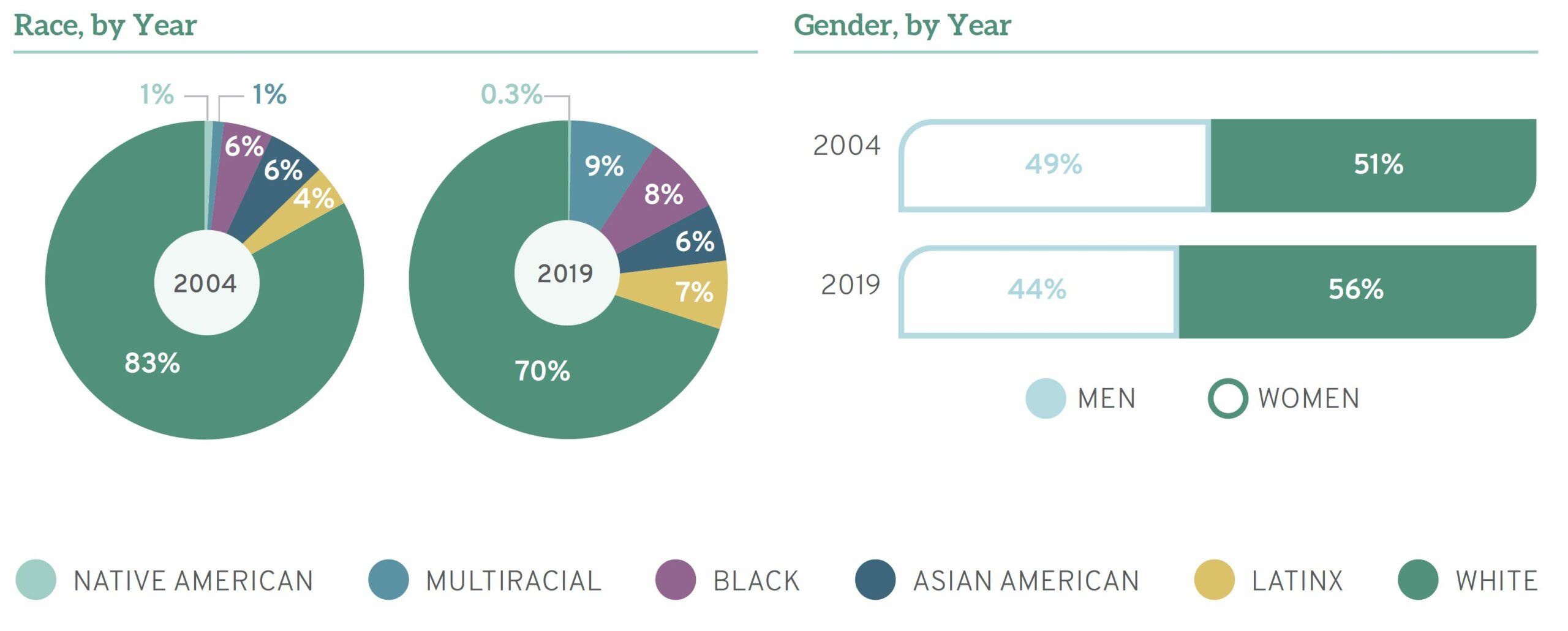

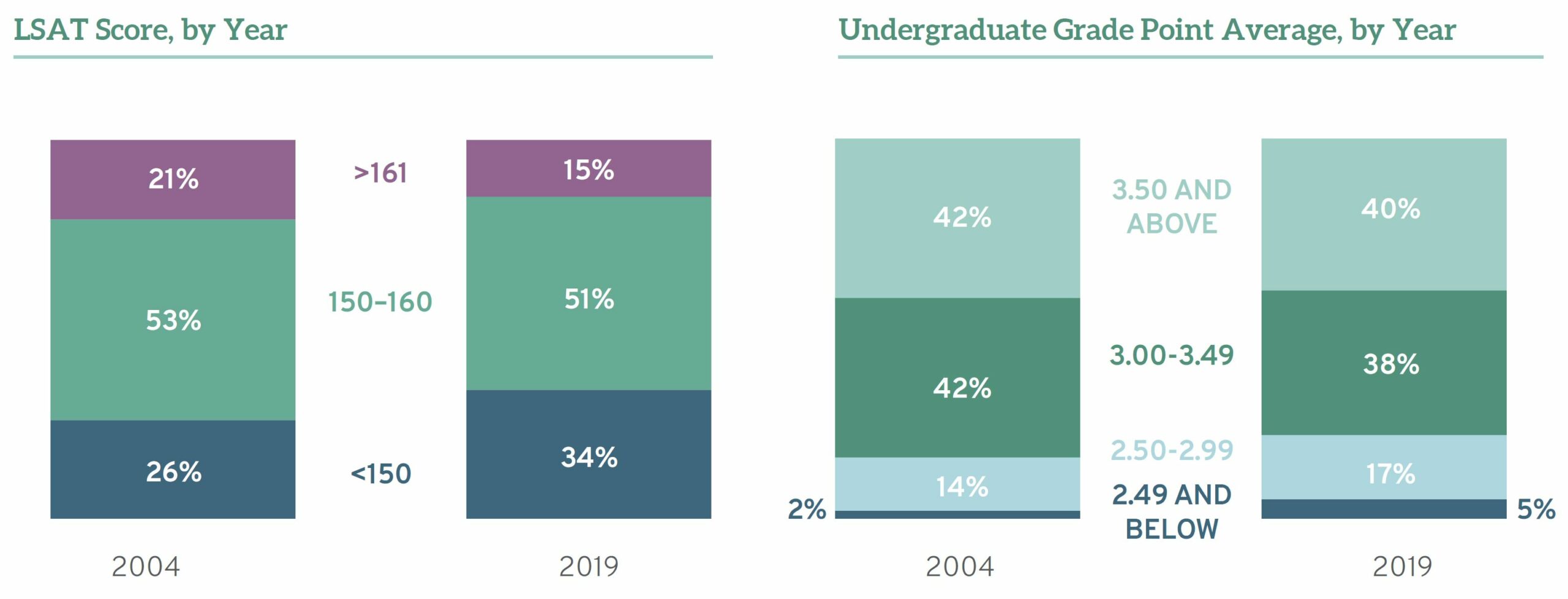

Conversation about increasing diversity and doing better when it comes to inclusion and belonging is everywhere in legal education. What’s critical though is empirically tracking how well we’re actually doing. The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provides invaluable and sobering data that should serve as a beacon to legal educators’ aspirational goals of cultivating diversity, inclusion, and belonging in their schools and in the profession. LSSSE’s 15-Year Retrospective – The Changing Landscape of Legal Education – tells us that there’s a positive trajectory with minority enrollments from 2004 to 2019.

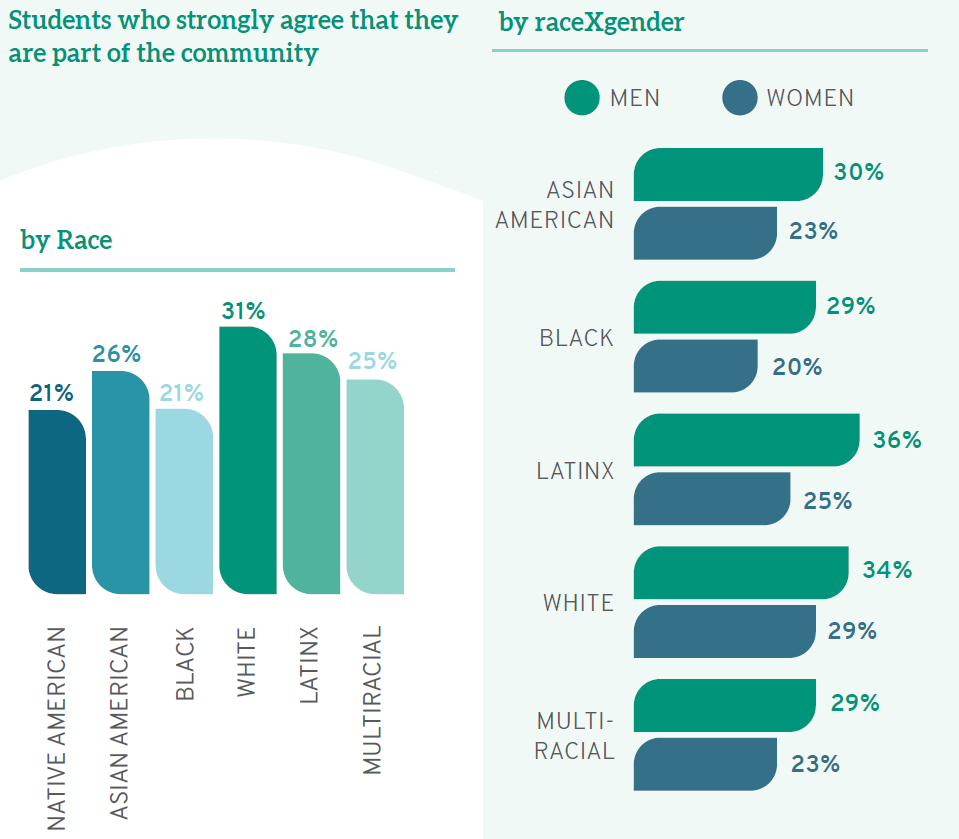

But the jarring news is that minority students’ sense of belonging – especially women of color students– is quite a bit lower than that of White students. As LSSSE’s 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Report points out, “Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.”

The data unequivocally tells us that we need to do a lot better for ALL law students to succeed. But the effort should start much earlier than when law students start law school. We need rigorous rethinking and innovation in law school admission practices – whereas to date the hyper-focus is on the limited numerical indicators of undergraduate GPA and especially LSAT score.

For the past three years, Southwestern Law School has innovated with such a first-of-its kind approach to admissions practices. The research project and initial results are detailed in “More than the Numbers”: Empirical Evidence of an Innovative Approach to Admission, Minnesota Law Review (Vol. 107, forthcoming), co-authored by the co-authors of this blog and Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, and will be presented at the Minnesota Law Review Symposium, on October 7, 2022, “Leaving Langdell Behind: Reimagining Legal Education for a New Era.” Interestingly, Southwestern’s empirically-based novel approach seems to have provided a notable boost to the matriculants’ sense of confidence or belonging in attending law school. More on that in a bit.

Southwestern’s project is driven by the moral imperative that law schools – as gatekeepers to the legal profession – should commit to innovative and rigorous admissions processes that define merit broadly and provide opportunities based on a spectrum of factors, beyond the traditional numerical indicators. In furtherance of this commitment, several years ago, Southwestern developed an evidence-based tool to more fully and meaningfully assess applicants’ law school potential. This tool goes beyond the limited cognitive measure of the LSAT, which many criticize as an impediment to diversifying law schools and the profession and which at best is only modestly predictive of first year law school performance.

Southwestern’s approach focuses on that group of applicants whose application materials show promise but also raise questions about the applicant’s current readiness for law school. These applicants are invited to participate in a methodical waitlist interview process where they are asked a series of questions based on several factors identified in the IAALS’s Foundation for Practice (“Foundations”) study as necessary for first-year attorneys. Three years into this project and based on hundreds of admission interviews working with Dr. Elizabeth Anderson we have analyzed our approach. The data has produced initial reliability and validity metrics for the measure developed – i.e., a tool that could be used with confidence in the admissions process.

Southwestern’s approach has included three steps. First, Southwestern identified what needs to be measured – i.e., certain foundations necessary for first-year practice as established by the Foundations study and hence assumed to be necessary to law school success. Second, the school identified why these factors need to be measured – i.e., to provide access to legal education with measures that matter. Third, the school designed the empirical research to support the development of a reliable and valid measure of this construct. Relatedly, Southwestern developed a measure of “nontraditional readiness for law school” using a design that focused on a psychometric research design, where psychometrics is the research practice of formal development of reliable and valid measures/assessments. Southwestern has found that the developed tool/measure is measuring what it set out to measure. This tool/measure will produce a score that will then be used in predictive validity analyses, as well as predictive modeling of law school success outcomes.

Interestingly, and beyond the quantitative data, based on comments shared by the interview matriculants, for purposes of adding context to the paper we’ve written about the admissions project, we’ve learned that the interview experience provided a notable boost to their confidence in attending law school. This was not an outcome that Southwestern had hypothesized or planned for but was a palpable part of the comments shared by the matriculants. Seeing the LSSSE data about belonging, it’s imperative that we create a sense of belonging starting with the admissions process.

The matriculant’s comments are indelible. A third-year interview matriculant noted:

I was very nervous when I came to the school for the waitlist interview. But afterward I felt heard and this motivated me. It gave me confidence, and I felt I couldn’t let the school down and I now had the opportunity to follow my purpose.

A second-year interview matriculant noted:

With the waitlist interview, Southwestern made the admissions process more personal and it showed me that the administration really values the lived experience of potential students and wants to hear what I have to say. This gave me confidence about law school and what I can contribute/accomplish.

And a first-year interview matriculant noted:

My waitlist interviewer dug deep and tried to understand me. She heard me, which was incredible. I knew law schools aren’t comfortable taking a chance but I was hoping some schools would want to hear my story and that’s what the waitlist interview did for me. This gave me the chance and confidence to pursue the dream that started with watching Fresh Prince of Bel-Air when I was a kid and thinking it’s so incredible to see Black attorneys and I want to be an attorney.

Our work has been well-received. We recognize, however, there is work left to be done and LSSSE is uniquely positioned to contribute in this area and help drive the necessary change through additional data. As part of its annual survey, LSSSE could include questions designed to gather data on law students’ admissions experiences. As our approach to admissions shows, establishing a sense of belonging can begin well before orientation. This unintended yet profound outcome is worth additional exploration. As indicated in the 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Report, a strong sense of belonging can make the difference in whether a student feels they have the support they need to thrive, especially women of color.

Further, as part of its longitudinal studies, LSSSE could also consider ways to track admissions factors beyond the limited indicators of LSAT and UGPA. The 2020 15-Year Retrospective – The Changing Landscape of Legal Education points out overall drops in UPGAs and LSAT scores.

This is helpful information, but the continued hyper-focus on these traditional factors, and not probing into and tracking other admissions-related data, contributes to perpetuation of limiting entry into law school and the profession based on narrow concepts of merit and potential.

These are just a few ideas. But to be sure, empirical inquiry and evidence must lead the way to change in admission practices. With its dedication in working for the betterment of legal education and its rigor in research practices, LSSSE certainly has a critical role to play in encouraging innovative law school admissions practices that more fully and meaningfully assess merit and potential while creating an inclusive and engaging pre-matriculation experience.