Guest Post: LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student

LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student

Elizabeth Bodamer, J.D., Ph.D.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Policy & Research Analyst and Senior Program Manager

Law School Admission Council

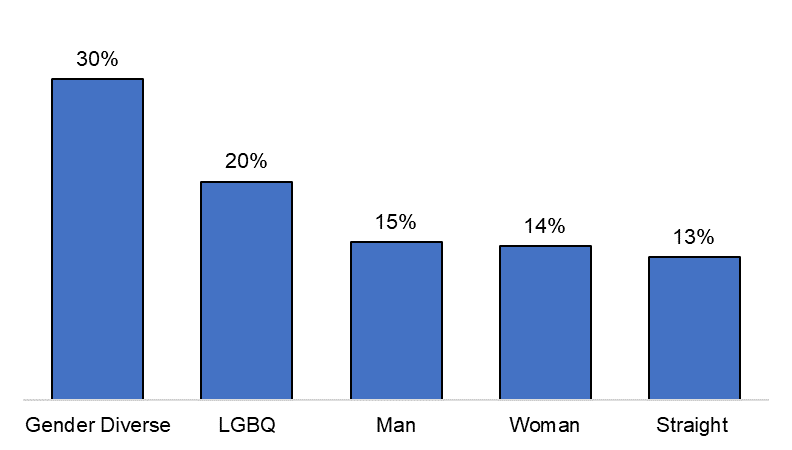

When navigating the law school enrollment journey, LGBTQ+ candidates face the challenging task of meeting two important criteria: finding a law school that meets their academic and professional needs while also providing a culture that will support their full authentic selves both inside and outside of the classroom. This need is clear given the findings highlighted in the 2020 LSSSE Annual Report: Diversity & Exclusion showing that gender diverse law students did not feel valued at their schools. Additional findings using data from the 2020 LSSSE Diversity and Inclusiveness module reveal that gender diverse and LGBQ law students were more likely than cis-gender and straight students to report not feeling comfortable being themselves at their law schools (Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1: Students Reporting Not Feeling Comfortable Being Themselves

Source: Data from the 2020 Law School Survey of Student Engagement Diversity and Inclusiveness Module. Data collected from over 5,000 law students across 25 law schools. LGBQ students represented about 14% of the sample and gender diverse students represented 1% of the sample.

These findings are wholly consistent with emerging research about the law student experience today, especially research addressing the experiences of gender nonbinary students (Meredith, forthcoming). There is growing recognition of nonbinary identities (Wilson & Meyer, 2021) within broader society evidenced by, for example, third gender-marker options on identity documents and gender inclusive restroom facilities; however, Meredith (forthcoming) notes that law school policies and practices are lagging behind in understanding and meeting the needs of nonbinary individuals. Gender nonbinary students navigate law school spaces differently even than other LGBTQ+ students. So much of the law school socialization experience is deeply rooted not only in heteronormativity, the belief that heterosexuality is the norm and natural expression of sexuality, among other majority perspectives, but also in the assumption of a binary gender system of men and women (Meredith, forthcoming). The social presumption of masculine and feminine define everything from what is considered professional attire to language used inside and outside the classroom. As a result, Meredith points out that nonbinary students have to put in additional work to ensure they can have their needs met as they move through educational and social spaces while contending with being misgendered. This creates an additional, sometimes insurmountable barrier to success in law school for some that is completely unrelated to their academic ability.

Within this context and recognizing the changing landscape of legal education and life for LGBTQ+ individuals since LSAC first administered the LGBTQ+ Law School survey over 15 years ago, in 2020 the LSAC Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity subcommittee approved a new and robust candidate-centric survey. The specific purpose of the 2021 LSAC LGBTQ+ Law School Survey was to collect information on how law schools support LGBTQ+ students.[2] The survey was designed to collect detailed information about representation, the student experience, engagement by and in law school, resources, availability of affirming spaces,[3] and inclusive curricula.

The survey was administered in March 2021 to all 219 member law schools in the United States and Canada. A total of 136 U.S. law schools from 47 states and 5 Canadian law schools provided responses. In the coming weeks, LSAC will release an aggregate report, “LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student,” that will offer a nuanced perspective on how law schools interact with and support LGBTQ+ students. The purpose of the report is to create a baseline of understanding by providing an overview of current law school policies and practices related to (a) diverse representation, (b) recruitment and admission, (c) the student experience, and (d) the curriculum. The results of this survey will have a number of immediate uses, including:

- Educating law school professionals about current LGBTQ+-related policies and practices in legal education in order to create a common understanding and baseline from which we can develop updates and advocate for inclusive and meaningful change.

- Developing strategic programming and resources for candidates and schools. This includes updating the LSAC LGBTQ+ Guide to Law School.

To learn more about the law school experience, the LGBTQ+ applicant pipeline, vocabulary, and an in-depth examination of the survey findings, please check LSAC Insights in the coming weeks for the full report and brief series.

References

Meredith, C. (Forthcoming 2021-2022) Neither Here Nor There. [Note] Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality.

Wilson, B. D. M. & Meyer, I. H. (2021). Nonbinary LGBTQ Adults in the United States. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute.

__

[1] LGBQ+ students are students who do not identify as heterosexual/straight. Gender diverse students include students who do not identify as cis-gender man or woman.

[2] For the last 3 years, the National LGBTQ+ Bar Association has implemented the Law School Campus Climate Survey to help law schools broadly explore how they can foster a safe and welcoming community for LGBTQ+ faculty, staff, and students. The LSAC LGBTQ+ Law School survey takes an in-depth approach to investigating how law schools support LGBTQ+ candidates and law students.

[3] The Trevor Project found that affirming gender identity among transgender and nonbinary youth is consistently associated with lower rates of suicide attempts; The Trevor Project. (2019). National survey on LGBTQ youth mental health. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2020/.

Valuing the Unique Experiences of Multiracial Students

Valuing the Unique Experiences of Multiracial Students

Meera E. Deo

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement

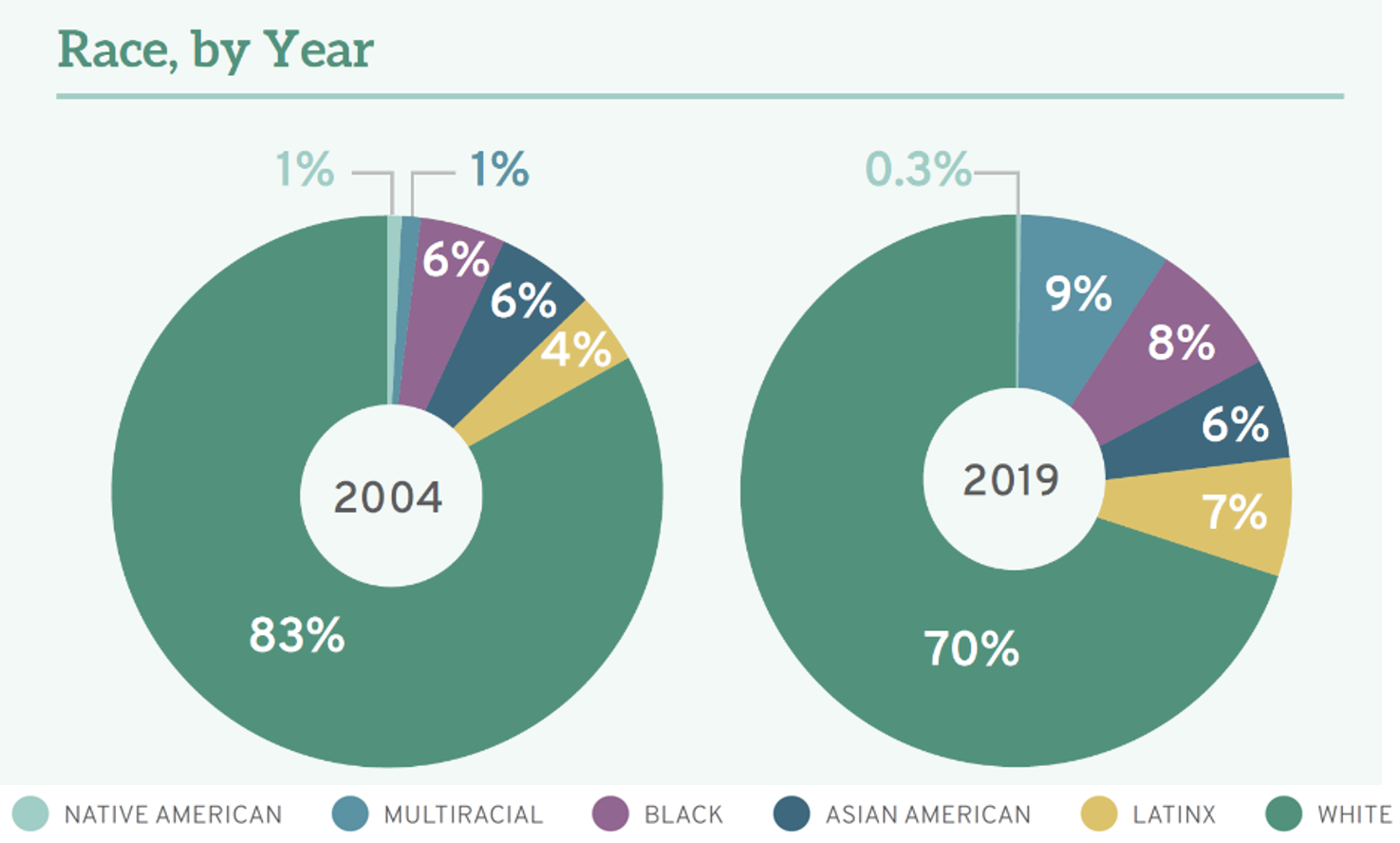

Multiracial people—those who identify as belonging to two or more racial groups—are a growing proportion of the US population. There are also more multiracial students in law school today than ever before. LSSSE data reveal that multiracial students comprised 9% of all law students in 2019, though only 1% of LSSSE respondents identified as multiracial in 2004.

Like other pan-ethnic groups, there is significant diversity within the broad umbrella group encompassing multiracial people. Their heritage can draw from ancestors who are Black, White, Asian American, Latinx, Native American, Middle Eastern, and more. And, of course, what a multiracial person with Black and Asian ancestry experiences in law school may be very different from what a Latinx and White student encounters. Despite this intra-group diversity, multiracial students as a whole do share some commonalities. Their experiences as a group tend to be different from those of White students but also from those of other students of color. I explore some of these distinctions in my new article, The End of Affirmative Action, noting: “Like their heritage, the multiracial experience is a combination of different backgrounds, often falling somewhere between those of other people of color and whites.”

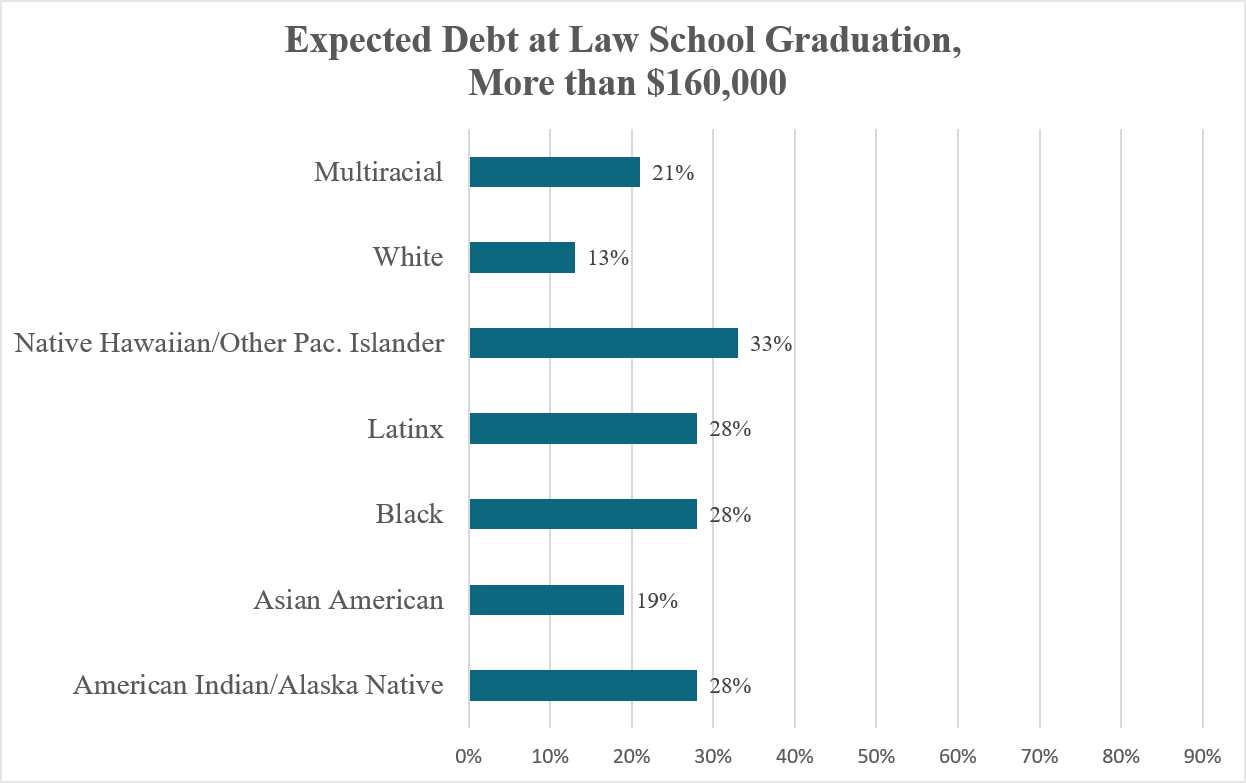

We can examine the unique experiences of multiracial students by examining both quantitative and qualitative measures. First, let’s consider debt. When LSSSE asked all students about the total amount of educational debt they expected to accrue by graduation, 28% of Black and Latinx students and 13% of White students expected to owe over $160,000. Debt levels of multiracial law students fall between the range of White and Black/Latinx students: 21% of multiracial students expect to owe over $160,000.

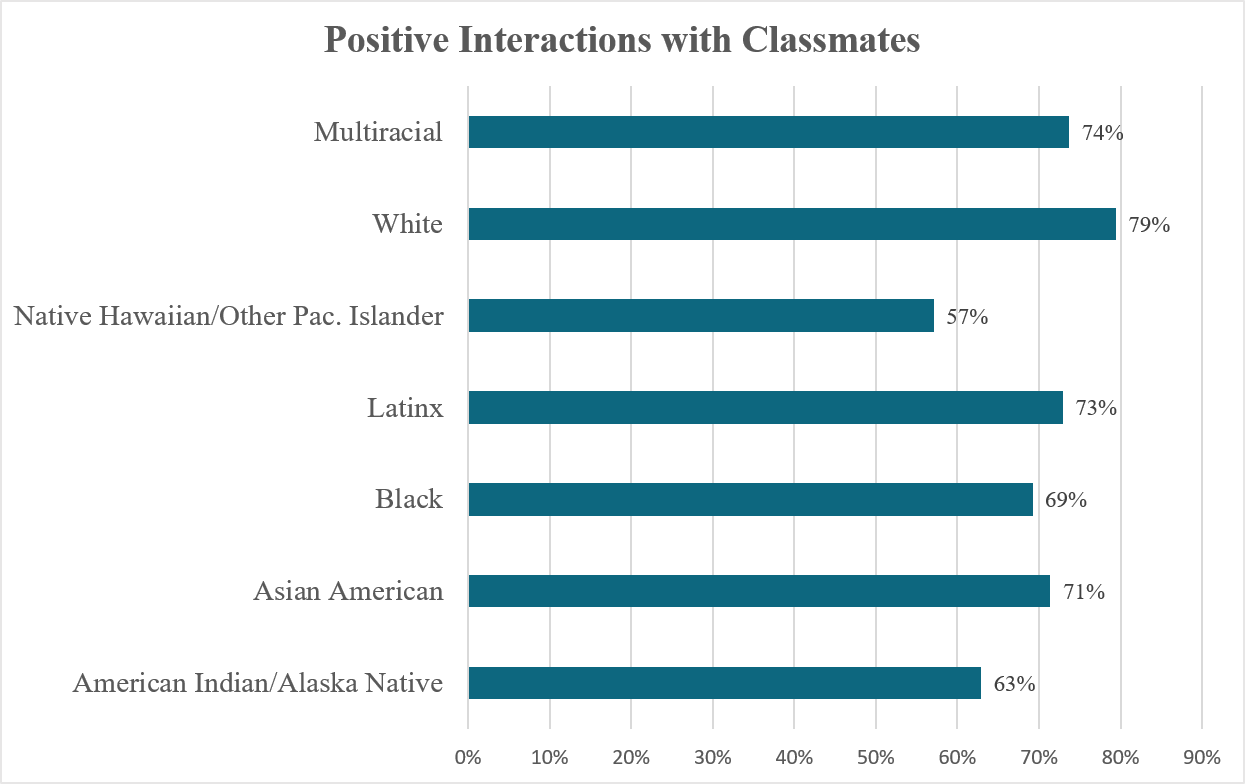

Moving beyond the debt numbers, we can also consider the quality of interactions between students. The LSSSE survey asks each student to rate the quality of their interactions with their classmates on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 references unfriendly classmates and strong alienation and 7 suggests friendly classmates and strong belonging. White students are more likely than any other racial/ethnic group to enjoy positive relationships with classmates, with 79% rating these interactions as 5 or higher. Lower percentages of Native American (63%), Black (69%), and Asian American (71%) students have equally positive relationships with classmates. As with debt, the experiences of multiracial students fall between those of White students and other students of color, with 74% rating their interactions with fellow students as positive.

Degli Stati membri dell'UE rappresentati dal Consiglio d'Europa https://unafarmacia24.com/ (CdE), dei gruppi di lavoro del CdE e del Parlamento europeo. I singoli Stati membri dell'UE sono rappresentati in questo processo dai gruppi di lavoro del CoE.

Despite experiences that clearly distinguish them from their classmates, multiracial students are rarely considered as a separate group. In fact, as I write in my new article, “Multiracial applicants and students are virtually invisible when it comes to considering affirmative action or educational diversity specifically.” Obviously, students with different experiences have unique contributions to make in the classroom as well as different needs to maximize their academic and professional success. Instead of ignoring them as a group, we should draw from the data to recognize the unique experiences of multiracial students. Administrators should also make efforts to meet the equity and inclusion needs of multiracial students that may be different from those of their classmates. Documenting, recognizing, and valuing our differences is how we improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in legal education.

Guest Post: Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now

Guest Post: Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now

Stephen Daniels

Senior Research Professor

American Bar Foundation

Shih-Chun Chien

Research Social Scientist

American Bar Foundation

In an earlier LSSSE guest blog post, we argued for greater attention to student motivations – to why people choose to attend law school and make a career in law.[1] We weren’t talking about just-so ideas of motivation like the “Trump bump”[2] or the escapist idea of avoiding a sour job market.[3] Such explanations, we said, “strip any real substance out of the idea of motivation, telling us little about the decision to attend law school and nothing meaningful about the choice of law as a career – and ultimately, this is the important issue.”[4]

We noted that “literatures in psychology and on organizations suggest that motivations can be important for understanding the outcomes of legal education, especially graduates’ career aspirations.”[5] Motivations become intelligible to the extent we can connect them to what students hope to do as lawyers.[6] The earlier blog was just the opening of a larger interest in motivation and the utility of LSSSE survey data, and this one furthers both.

Two LSSSE surveys are unique for exploring those motivations and career aspirations. One is older -- the 2010 LSSSE survey, and one newer -- the 2021 LSSSE survey. In addition to the full suite of annual survey questions (which included questions related to aspirations), each asked seven motivation questions to a subset of the survey participants. Those questions asked students to rate each of the seven motivations on seven-point scale from “not at all influential” to “very influential.”

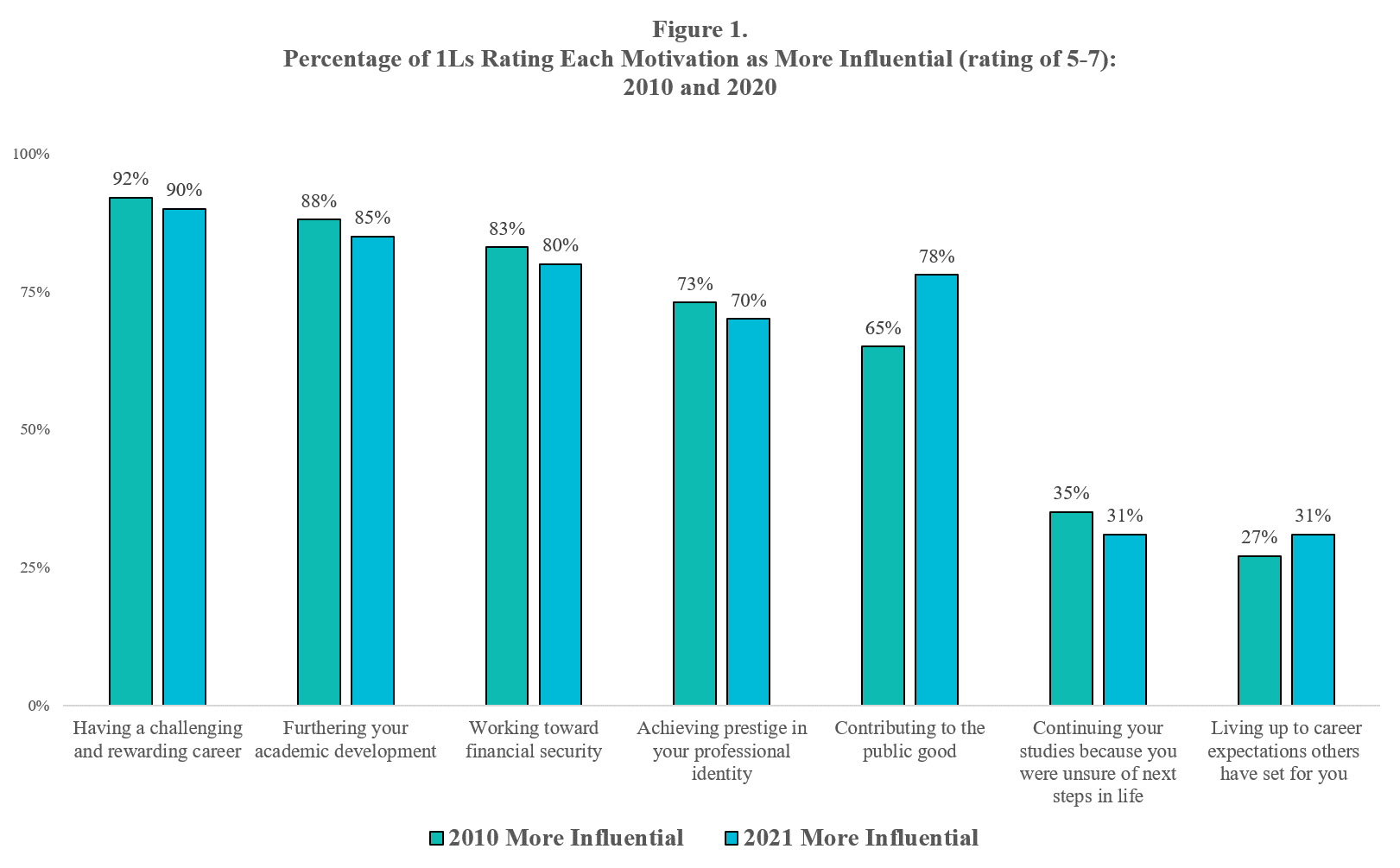

We delved into the 2010 motivation data just a bit in the earlier blog to illustrate the range of student motivations and their relative importance (4,626 respondents, 22 law schools) and we return to them here.[7] Figure 1 below shows the seven motivation questions and their relative importance for the students in the 2010 motivation subset. The percentages are for 1L respondents only -- they are closest to the decision to attend law school. Most important for the 2010 respondents are the intrinsic, inward looking, motivations of “a challenging and rewarding career” and “furthering one’s academic development.” The extrinsic, outward looking, motivation of “contributing to the public good” is much less important.

In a subsequent paper we began exploring that connection between motivations and aspirations using the same 2010 data.[8] Our interest there is in the links among motivations, preferred area of legal specialization,[9] and working in the criminal justice system, especially those wanting to work in a prosecutor’s office (or alternatively, in a public defender’s office).[10]

Viewed through the lens of motivation, those students in the 2010 motivation subset interested in criminal law saw contributing to the public good as a more influential motivation than did their peers interested in some other area of legal specialty. Their non-criminal law peers saw working toward financial security financial security as more influential.

Revealing a sharper contrast are the students interested in corporate and securities as their area of legal specialty. They are, in a sense, mirror opposites of the criminal law students in being driven much less by the public good, driven much more by financial security, and somewhat more by prestige. Only 39% of those interested in corporate/securities see public good as more influential compared to 72% for those interested in criminal law. The two groups of students clearly value different things and have different aspirations.

Having worked with the 2010 data and wanting something more contemporaneous, we asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions to the 2021 survey, and they generously did so. Those seven questions were asked to a subset of the 2021 survey participants (2,930 respondents, 15 law schools).

The 2010 data, while important in and of themselves, are just a snapshot in time. In wanting the 2021 data the key question for us is one about stability v. change. Are there any noticeable changes in student motivations, the interactions among motivations, and their connections to student aspirations? If so, what might help explain any change. The general patterns over time in the LSSSE data for job expectations would suggest relative stability rather than change.[11] Events in the broader societal environment since 2010 might suggest otherwise.[12] Our initial thought is the null hypothesis of no real change in motivations, which while generally the case isn’t in one important way. That exception involves the motivation of contributing to the public good.

Not only about the 2010 respondents, Figure 1 also presents a simple comparison of responses to the seven motivation questions in 2010 and in 2021 by 1L students.[13] The bars represent the percentage who reported that a motivation was more influential for them (a rating of 5, 6, or 7 on the seven-point scale). At first glance one sees a relatively stable pattern between 2010 and 2021, with small decreases in the degree of influence. The intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development remain the most intense motivations followed by financial security.

One thing, however, stands out in an otherwise expected pattern of relative stability. Public good – an extrinsic motivation that is of particular interest to us – disturbs that pattern. Rather than the very slight decrease for the substantive motivations (all aside from “unsure of next steps” and “others’ expectations”), its influence is more important in 2021. Its influence became more important than prestige and close to that for financial security.

Digging a bit deeper into the data, we found that this increase does not appear to be just a matter of some general increase in the importance of public good. Instead, it is a matter of the intensity of the influence, and this is the most interesting finding. Again, the percentages in Figure 1 includes those giving a rating 5, 6, or 7. If we break that figure down, we see that the percentages for ratings 5 and 6 are essentially identical for the two years. For 2010, rating 5 = 17% and for 2021, rating 5 =17%. For 2010, rating 6= 17% and for 2021, it is 16%. For the highest, most intense rating we find 32% in 2010 and 45% in 2021. There is no comparable increase in intensity for the other substantive motivations (the greatest was for financial security, from 43% to 46%).

While our analyses looking at the characteristics of the students and schools involved in the two surveys are continuing, there are two matters worth noting concerning the public good, change, and intensity. Although quite different, both are instructive. The first involves gender. Female respondents rate the public good as more influential than their male counterparts in both surveys. For both groups, however, intensity increased as reflected in the percentage rating it at the highest ranking. In 2010, 37% of female respondents rated public good as very influential, while 23% of males did. In 2021, the percentages were 49% and 30%, respectively.

The second involves a very different way of looking at change and intensity – comparing students in particular schools rather than students in general. Two schools appeared in each motivation subset, allowing us to at least explore this. Because of the way in which LSSSE prepared the two data sets for us (using a unique code for each participating school that does not allow us to identify the school), we were able to find two schools appearing in 2010 and in 2021. For one of the schools the percentages of responding students rating public good at the highest level in each year are 25% and 41%, respectively. For the other school the comparable percentages are 20% in 2010 and 34% in 2021. Important here, as with gender, is not the exact percentages themselves (although those figures are not, of course, unimportant), but the idea of change in intensity even if the starting points were different. In short, something appears to be going on regarding student motivations.

Our comparative findings concerning change, though quite preliminary at this point, reinforce the importance of motivation for the study of legal education and the legal profession. An influx of students highly motivated by contributing to the public good has implications for both. It may shift the dynamics of the legal employment and increase the pool of graduates who aspire to much needed public service careers. At the same time, it means that law schools will need to provide the educational opportunities and support for those students to succeed, something not always the case. This could include working more closely with public service employers to provide needed opportunities and support.

___

[1] Stephen Daniels & Shih-Chun Chien, “Beyond Enrollment: Why Motivations Matter to the Study of Legal Education and the Legal Profession,” Guest Post, LSSSE Blog, September 24, 2020, ), https://lssse.indiana.edu/blog/guest-post-beyond-enrollment-why-motivations-matter/.

[2] Stephanie Francis Ward, “The ‘Trump Bump’ for Law School Applicants is Real and Significant, Study Says,” ABA Journal, February 22, 2018, https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/the_trump_bump_for_law_school_applicants_is_real_and_significant_survey_say; Karen Sloan, “Forget the ‘Trump Bump:’ First-Year Law School Enrollment Dipped in 2019,” December 12, 2019, Law.Com, https://www.law.com/2019/12/12/forget-the-trump-bump-law-school-enrollment-dipped-a-bit-in-2019/.

[3] Louis Toepfer, “Introduction,” in Seymour Warkov and Joseph Zelan, Lawyers in the Making (1965); at xv.

[4] Supra note 1 at 2.

[5] Id at 4.

[6] Id at 5.

[7] See supra note 1 at 6.

[8] Shih-Chun Chien & Stephen Daniels, “Who Wants to be a Prosecutor? and Why Care? Law Students’ Career Aspirations and Reform Prosecutors’ Goals,” Howard Law Journal (forthcoming 2022), using 2010 data to explore connections among motivations, preferred area of legal specialization, and preferred work setting upon graduation.

[9] The 2010 LSSSE survey asked students to choose from a list of 26 areas of legal specialization for their preferred area of specialization upon graduation.

[10] The analysis includes the issues of diversity and gender. One interesting finding is that African-American males interested in criminal law are more likely to eschew work as a prosecutor or as a public defender in favor of private practice. AAPI students are the least likely cohort to choose criminal law as their area of specialization.

[11] The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective (2020) at 9, https://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/LSSSE_Annual-Report_Winter2020_Final-2.pdf.

[12] We are particularly interested in whether the rise and proliferation of progressive prosecutors and other recent civil justice reform/Black Lives Matter-type movements and anti-Asian hate crimes affect law students’ motivations and career aspirations.

[13] Our earlier blog reported on 1Ls who rated each motivation in 2010 at 6-7 (the two highest ranks). Here Figure1 reports on respondents who rated each motivation at 5-7. This is consistent with the approach we used in supra note 9. It also allows us to accentuate the changing intensity for motivations.

Guest Post: Penalizing Preventative Mental Health Treatment for Law Students

Guest Post: Penalizing Preventative Mental Health Treatment for Law Students

Doron Dorfman

Associate Professor of Law

Syracuse University College of Law

The study of mental health of law students can be traced back to the late 1960s when research published in the Wisconsin Law Review found that “failure anxiety” has been a serious impediment for first-year law students’ ability to study. Research from the 1980s all the way to 2016 has shown that the stress and anxiety is not only a problem found among 1Ls, but also one that continues throughout the law school journey.

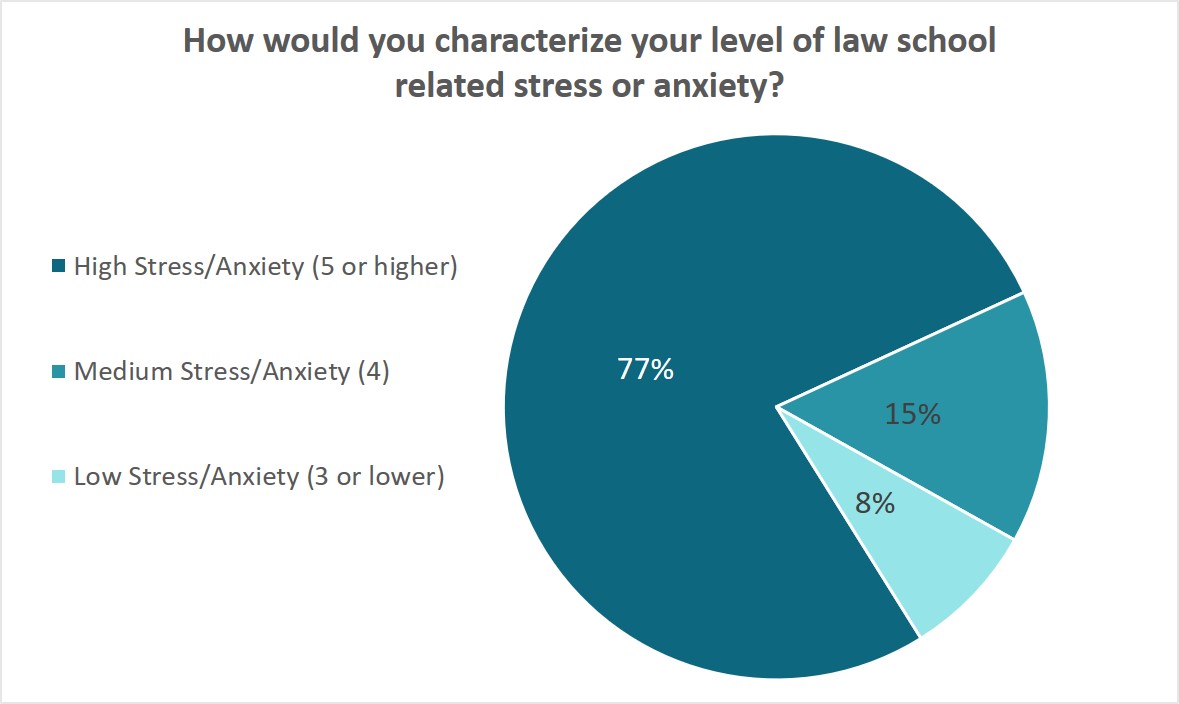

It has been known for decades that attending law school is an extremely stressful experience. As recent LSSSE data demonstrate, attending law school remains stressful and anxiety provoking. A 2020–21 LSSSE survey module based on a sample of more than 2,000 law students shows that 77% percent of the students surveyed found the level of stress and anxiety in law school to be a 5 or higher on a 7-point Likert scale.

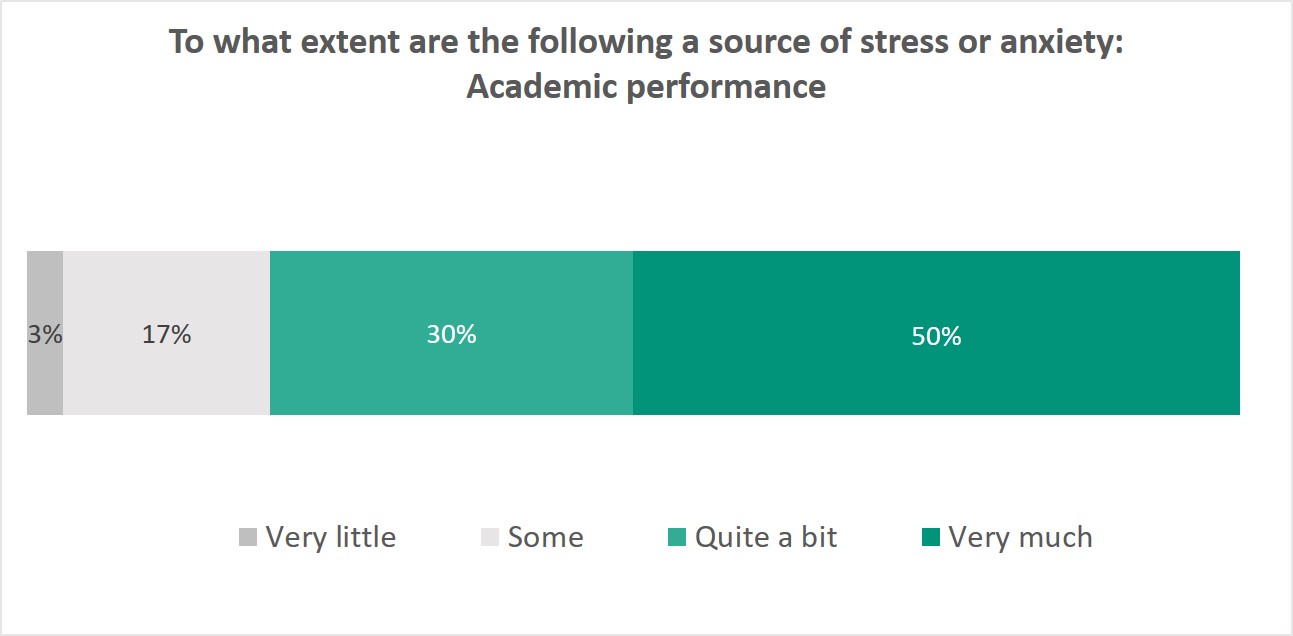

Much like the peers from 50 years ago, 50% of the sample say that the source of their stress or anxiety is “very much” due to concerns about academic performance.

In a new research project, I examine what I call the “the paradoxical legal treatment of preventative medicine” showing how while the law on the books, specifically the Affordable Care Act, contains avenues to promote and encourage preventive medicine, those efforts clash with other policies and decision-making processes that in action penalize those who take preventative measures. This contradiction creates a chilling effect on those trying to take preventative health measures and impedes the ACA’s original goal of promoting this important tool to foster the quality of health care.

One of the examples of this phenomenon is the Character and Fitness evaluations state bar associations conduct around the country, used to admit prospective lawyers into the bar. These evaluations take into account the students’ mental health history. In a 2016 study, it was found that the number one reason for students not seeking mental health treatment, which can be classified as “secondary prevention,” one that is practiced after the illness has been diagnosed but before it has become symptomatic, is the potential threat to bar admission.

As one law student recently acknowledged, he refused to seek out mental health resources when law school stress was becoming too much, as he did not want to risk being flagged during the state bar’s Character and Fitness evaluation. Instead, he developed a drinking habit to relieve his stress.

As I trace in my new work-in-progress over the last 30 years since its enactment, the Americans with Disabilities Act limited the inquiries state bar associations can make in regard to a candidate’s past mental health treatments. Some courts have also adopted a behavioral approach, whereby prior mental health treatments, and even current counseling, do not in and of themselves deem a person unfit to practice law if no present behavioral issues exist. Yet the problem of penalizing preventative mental health treatment in the context of state bars’ character and fitness evaluations persists in other states as indicated by a 2019 report by the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law.

Updated data on the mental health of law students, such as those collected by the LSSSE, are crucial for continuing the efforts to stop penalizing those seeking professional help for their stress and anxieties during law school. As I show in my work, it is another important arena in which the need to make sure the law promotes preventative medicine is particularly acute.

Ensuring that all state bars across the country find ways to balance the need to ensure applicants’ qualifications as competency and good moral character without penalizing and stigmatizing mental health treatment is a crucial goal that also holds the promise of diversifying the legal profession.